What do Moneyball, cattle ranching, and accounting have in common?

A pivotal scene in the 2011 movie Moneyball ends with the punchline, “How can you not be romantic about baseball?” The moral was that while baseball was moving towards statistics and quantitative analysis, everything still came down to people. For all the averages and benchmarks, on any given at bat a human drama was unfolding.

Over my two years at Ambrook, that’s how I have come to feel about accounting. On the surface, you have a ledger with debits and credits or incomes and expenses. Underneath you have a story: risks and rewards, trials and tribulations, choices and constraints. Most importantly, it’s a story about people.

At Ambrook we spend a lot of time working with people. Some are entrepreneurs getting a business off the ground, some are transitioning family-run businesses, some are striving to make the world a better place. The product we make helps people understand and tell their stories. And, when the timing is right, we help people make important business decisions that will shape their futures. The numbers are only one small part of the story, but they have a big impact. When you see a concept click for someone — their eyes light up and they start to talk excitedly about the future — the value proposition is undeniable.

Despite my enthusiasm for accounting, I wouldn’t try to claim that it’s fun: The value is in the process, not the product. Like so many lessons — in baseball or in bookkeeping — the most important learnings come from getting practice and reps. Getting your hands dirty and doing the books helps you get a sense for what is actually going on with a business. Accounting for a loan helps crystallize how money flows back and forth between the balance sheet and the income statement. You build intuition that helps you figure out when something seems incorrect. Before I started at Ambrook, I would have said that I know how accounting works; now I think I know how accounting feels.

The core idea behind Moneyball is that before analytics were popularized, people were looking at the wrong things. Scouts would go to college games and index on swing mechanics or if a pitcher had good stuff. As a result, talented players would go unnoticed and overlooked. In many respects that’s the case with agriculture today — the first sector we’ve focused on serving. In an industry steeped in culture, doing things the way they have always been done feels safe.

About a year ago, I visited a ranch customer in Southern California. I had helped set them up on the app, spent time cleaning up the balance sheet, and learned about their business in detail. I knew how the prior year’s income had been impacted by rainfall and why the question of “how many replacement heifers should I keep this year” is actually non-trivial. I had read extensively about livestock accounting and talked to industry experts about best practices for ranch financial management.

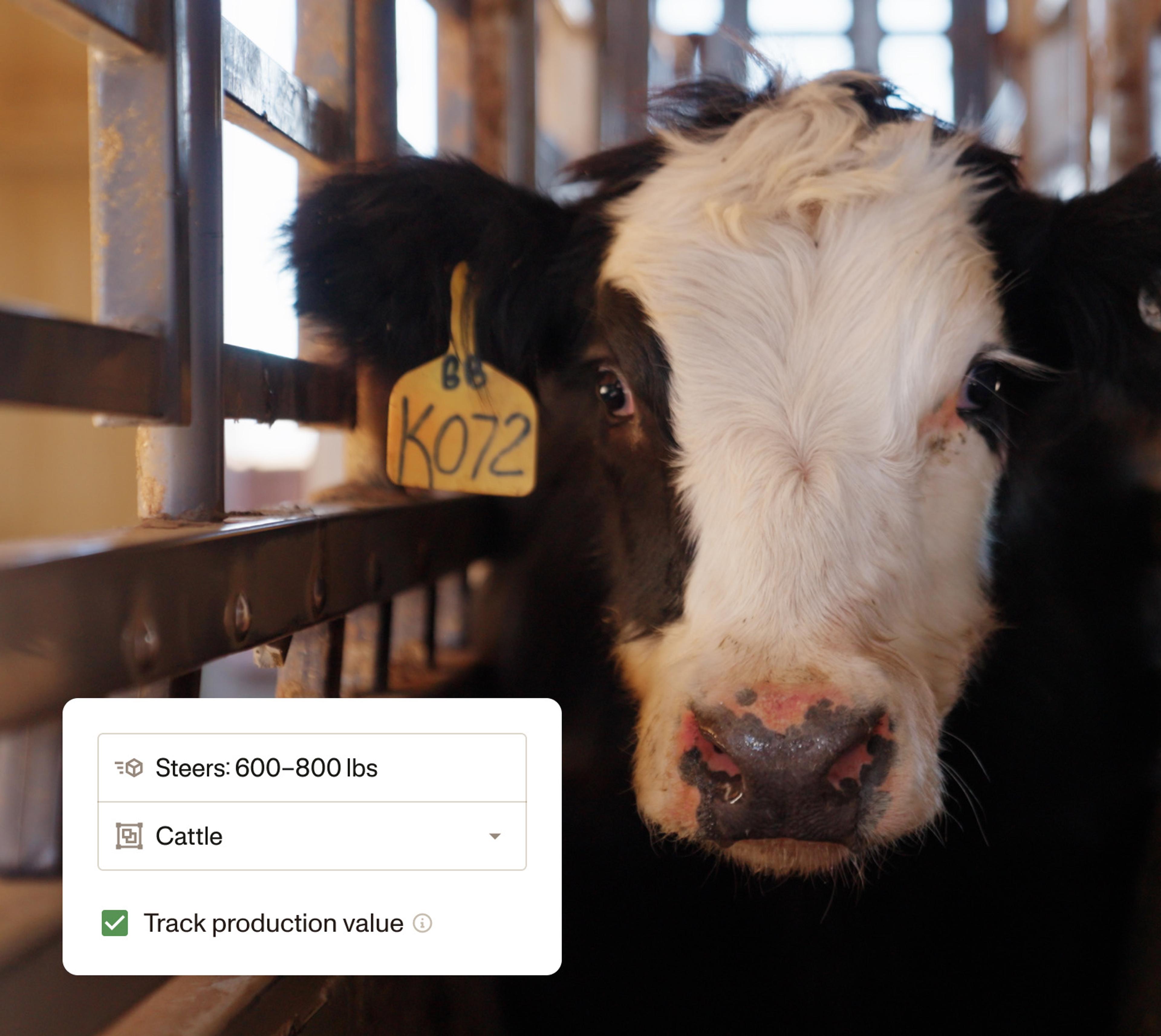

This was all well and good, but the story truly clicked when I was on the ranch at 5:15 am on a crisp October morning and I finally met the calves. In accounting terms, the calves didn’t exist. They were farm-raised, so according to conventional accounting methods they had no value. (Cash-basis businesses aren’t required to go through the exercise of capitalizing the expenses to raise these animals onto the balance sheet.) But in practical terms, they were an asset. They represented years of hard work. There’s no way to be out on a ranch, look at a calf crop, and think that those animals don’t matter.

So, we went about upgrading the accounting. Using Ambrook features like enterprise tags and pulling from livestock accounting practices, we figured out exactly what those calves were worth, in terms of the expenses laid out to raise them. We were able to calculate the breakeven price for calves and compare the profit margin of selling at commodity market prices versus selling direct to consumer. Retaining half the herd went from looking like a major net loss on a cash basis to looking like a sensible investment in the future.

An overused adage you might get in the classroom is that “accounting is the language of business,” but it is directionally correct. In baseball you can compare a pitcher to an outfielder using a statistic known as wins above replacement — in accounting, we have return on assets. Financial metrics are a way to look at two completely different things and try to make a statement about which is better, while still acknowledging that “better” is a human term. Better for what, or better for whom. Some folks want to maximize cash, others want to minimize risk.

The thing I have valued the most working at Ambrook has been having the chance to talk about what better means for hundreds of people all across the country. Accounting is just a useful entry point to the conversation. The learning has been that there’s no right answer. We can help with a cost of production analysis, or scenario planning, but the best option is all about the people we serve. When you think about a job in those terms — how can you not be romantic about accounting?