I ran Ambrook’s first engineering internship this summer with a simple goal: Build a repeatable early-career pipeline. I’m a software engineer at Ambrook — joined two years ago — and I’d been wanting to bring on interns since the beginning.

We’d hesitated in past years. Interns are an investment; as a small team we weren’t convinced we had the mentorship capacity, interview bandwidth, or project scaffolding to do it right. Last fall, I pitched the idea to the team: Treat it as a pilot, prove the value, and build something repeatable. We would bring on interns to ship real customer-facing work and establish a repeatable process we could scale for internal onboarding and early career recruiting. This summer we finally ran the experiment, setting out to bring on two engineering interns but ultimately bringing on one.

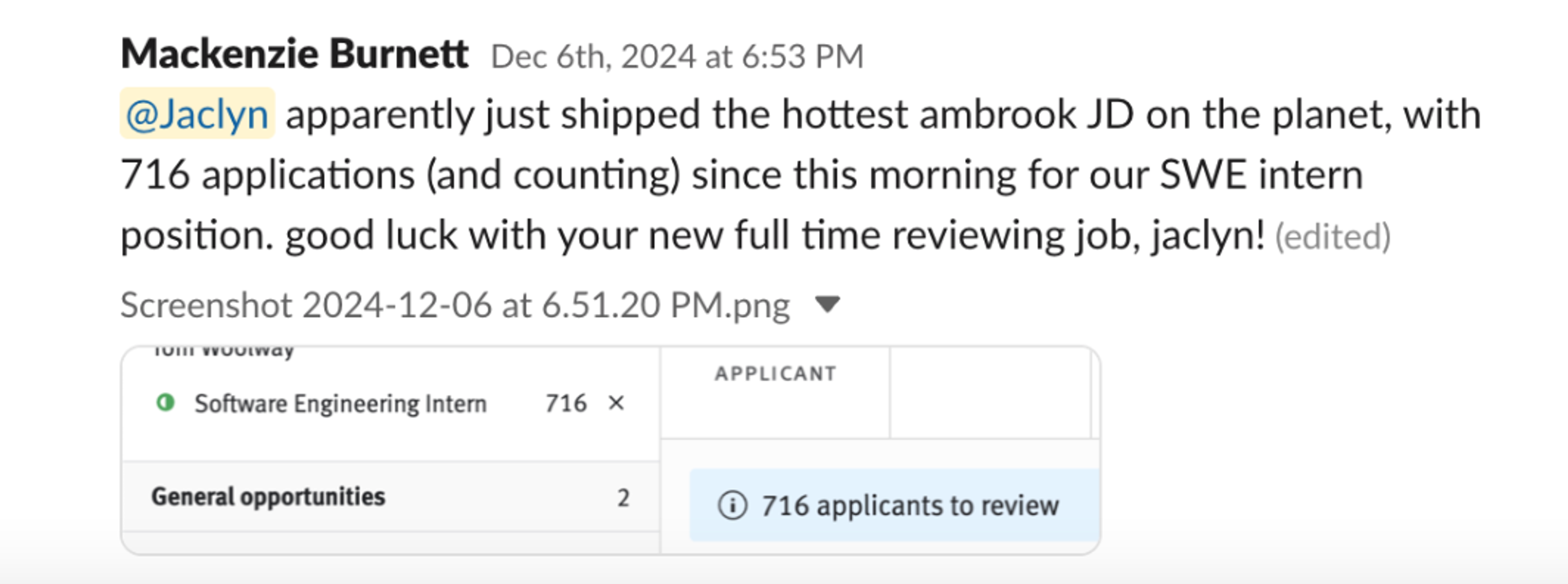

I made a candidate guide, posted on LinkedIn and Twitter, and waited. I didn’t know what to expect, maybe a few hundred applications?

Over 3,000 students applied between December and March. We manually reviewed more than a thousand, interviewed dozens, and ultimately hired Sam (who was incredible). Here are field notes on what I learned.

Why This Was Worth Doing

Our hesitations were real: Bringing on a few interns for the summer costs about the same as hiring one full-time engineer. That’s a tall ask for an early-stage startup! Add in interview time, selling the role, and structured onboarding, and you’re committing 1-2 engineers per intern across mentoring, managing, and onboarding. When you treat interns as overhead, you’re focused on what you’re giving up: time, resources, short-term velocity.

But that’s the wrong way to think about it — this was an investment in team capacity to train and uplevel each other. We wanted to codify what we’d been handling ad hoc — clear interview rubrics, a manager/mentor model with defined responsibilities, better onboarding documentation. The program would force us to build these systems, and I’d own it end-to-end: internal buy-in, sourcing, interviewer calibration, closing candidates, and creating repeatable processes. The hypothesis: Investing in a structured program would make all future onboarding less brittle and give our team reps in mentorship and leadership.

We ended up applying everything we learned to this year’s recruiting cycle and it made a massive difference. This time we started earlier in the recruiting cycle, focused heavily on outbound from day one, and pre-blocked engineering calendars into sprint windows for interviews. Instead of 3,000+ applications drowning us in noise, we got 150 targeted applications and moved fast.

The results: 50 intro calls, 20 technical assessments, 6 onsites. By the end of September (just 20 days after posting!) we extended 2 offers to candidates we were genuinely excited about.

Last year the process took over three months. This year we went from job posting to accepted offers in three weeks. The learnings from last year helped us turn what felt ad hoc into something repeatable.

Recruiting

When I first started last year’s recruitment process, my first mistake was thinking high volume meant a healthy pipeline. Within hours of posting the application, we received hundreds of applications. Over the first few weeks, we received thousands. But that didn’t mean there were thousands of qualified applicants.

The standout candidates had tangible signals: projects, websites that showed taste, thoughtful short answers. However it was hard to identify these qualities from among the pile of thousands. The best pipeline ended up coming from referrals, fellowships, and school communities, not the job board firehose.

We also quickly learned that timing matters. Many tech companies, particularly Big Tech, recruit in late summer/early fall for the following summer. We started in December, when top students had already signed offers. We lost strong candidates due to it.

One thing we got right was creating an in-depth candidate guide. It outlined our philosophy on early-career mentorship, answered common questions, and doubled as a pitch. Many students prefer bigger, more established companies with well-known recruiting processes and strong brand recognition. The candidate guide self-selected for the right people who were eager to dive into the scrappiness of a startup. Those who read it asked sharper questions and moved faster. I thought about it as a search query to find intentional, curious, and scrappy people who’d fit at Ambrook.

By January, inbound applications dipped. My triage backlog was full of people I should’ve contacted earlier who got lost in the application pile.

I asked for personal intros and sent personalized notes to dozens of candidates. This ended up being the highest quality group of applicants.

I pivoted to outbound. I went through my network — former colleagues, friends still in school, campus communities. I asked for personal intros and sent personalized notes to dozens of candidates. This ended up being the highest quality group of applicants.

For technical interviews, we invested upfront in getting our questions right, iterating to establish a consistent pass bar for future cycles. We also experimented with a take-home test for cold applicants after noticing many failed the technical phone screen. Take-homes are useful for early-career hiring and making sure folks pass the technical bar earlier in the process, but we also lose out on the opportunity to sell candidates on why they should be excited about working at Ambrook. We saw significant drop-off and removed them from the process this year.

Last year, between waves of inbound and outbound sourcing, the take-home experiment, and interview calibration, the entire process from application posting to hire took over three months. Spacing out interviews and switching between intro calls, technical screens, and team chats required context switching from the eng team. It wasn’t efficient.

My recruiting takeaway: Start earlier in the school year, be intentional with outbound, and pre-block calendars to run sprint windows — defined periods for intros, technicals, and team chats.

The Intern Experience

Once we found Sam, the hard part began: choosing an impactful project and creating the conditions for him to thrive.

Many companies park interns on side projects. We decided Sam would work on an important strategic project, just like any other engineer. Startups don’t know what that project is months in advance, so we did selection closer to Sam’s start date. About a month before he joined, customer feedback converged on a longstanding request: taxes, fees, and discounts on invoices. It touched core accounting and multiple product surfaces, had clear user impact, and could be scoped to ship in 8-10 weeks with room for fixes and side quests.

We started onboarding with an architectural walkthrough tied directly to that feature and set a steady cadence: three check-ins a week, plus availability for quick huddles when progress stalled. We held ourselves to fast code-review turnarounds so momentum didn’t die in someone’s PR review queue. In week two, Sam shared his onboarding learnings with the wider team. We’re still figuring out how to scale engineering onboarding, so fresh eyes and a quick feedback loop helped!

Shipping is the best teacher. Our weekly Weeding Day, a day we set aside to focus on customer quick wins, doubled as an onboarding accelerant. Sam moved across the codebase, fixed real issues customers noticed, and built context faster than any toy project could provide. While working on general bugs took time from his main project, he got exposure across product surfaces and worked with more people on the team. Sam became a fan favorite with our customer success team whenever he shipped a highly requested fix. And he got to witness real-world customer impact like any full-time employee.

To anchor the work in reality, we put him in the room with users: design-partner calls and UX research sessions tied to his scope. He joined engineering and all-hands meetings, came to our engineering retreat, helped at our summer soiree “Lettuce Party,” packing CSA bags for guests and even visited 4K Cattle, one of our design partners in Missouri!

We only brought on one intern instead of our initial plan for two, but the timing worked out. A few new full-timers started during his term, so onboarding Sam alongside new peers created a lightweight cohort anyway. New joiners swapped notes and unblocked each other as they onboarded. If we can batch intern start dates with new hires in the future, we will.

Midway through summer, I ran a formal midpoint review synthesizing input from engineers, designers and product specialists across the team working with him. It helped us step back and create a specific, actionable growth plan. It’s easy to get caught up in the day-to-day chaos of an early-stage startup, so setting aside dedicated time for feedback was important for investing in early-career growth.

Reflecting

An intern program isn’t just about building an early-career pipeline. The team gets stronger: We build mentoring muscle, turn onboarding into a repeatable process, and spread institutional knowledge.

If you’re running your first intern program, I hope this saves you a few cycles. Start recruiting earlier in the school year, be intentional with outbound, and treat it as an investment in team capacity.

And if you’re an engineer looking for your next opportunity, whether an internship or full-time role, we’re hiring! We’re looking for people who want real ownership and measurable outcomes. That’s how we think about hiring at Ambrook — every new person is a chance to level up the entire team.