Many farmers aren’t convinced that adding solar panels to their cropland is the right move. New research on light spectra efficiency could help.

As anyone who has used grow lights can attest, using differently colored lights to encourage plant growth isn’t new science. But a recent computer model shows that farmers can use colored lights to optimize both solar energy and crop production — assuming the right type of solar panel becomes more accessible.

To rid America’s power grid of carbon emissions, the country needs more solar power. A lot more. Federal estimates indicate that the amount of solar energy needed to achieve complete decarbonization would require about 10.3 million acres of land — roughly 1.15% of America’s current total farmland.

Installing that much solar will require convincing more farmers to let developers install solar panels on their working farmland — a buzzy synergy referred to as agrivoltaics. To that end, Majdi Abou Najm, one of the researchers behind a new computer model, thinks their results could prove persuasive.

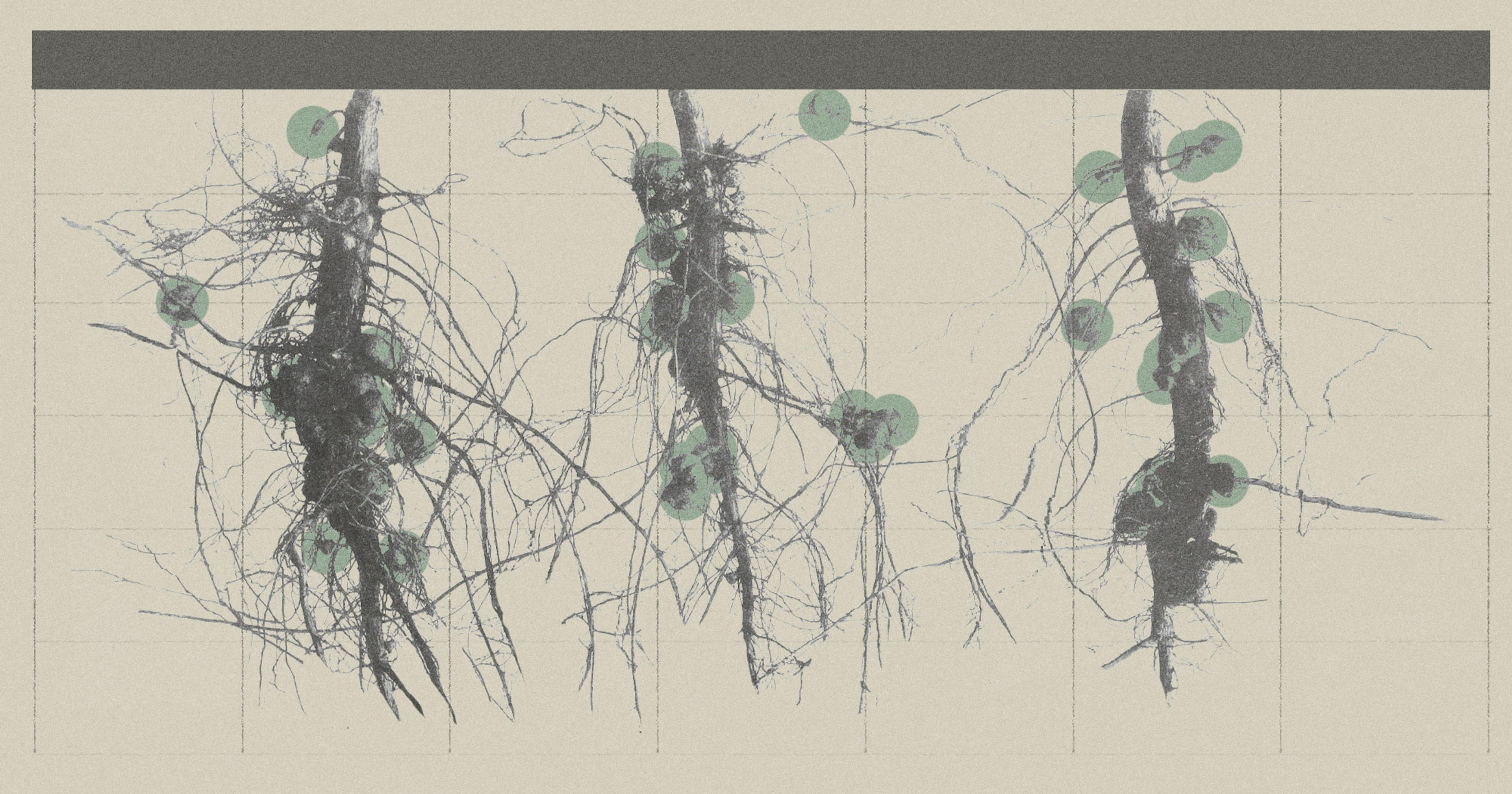

Abou Najm, professor of soil biophysics at the University of California, Davis, recently co-published a research article in Earth’s Future with Fulbright visiting scholar Matteo Camporese, describing how key plant productivity factors change when a plant is exposed to different light spectra.

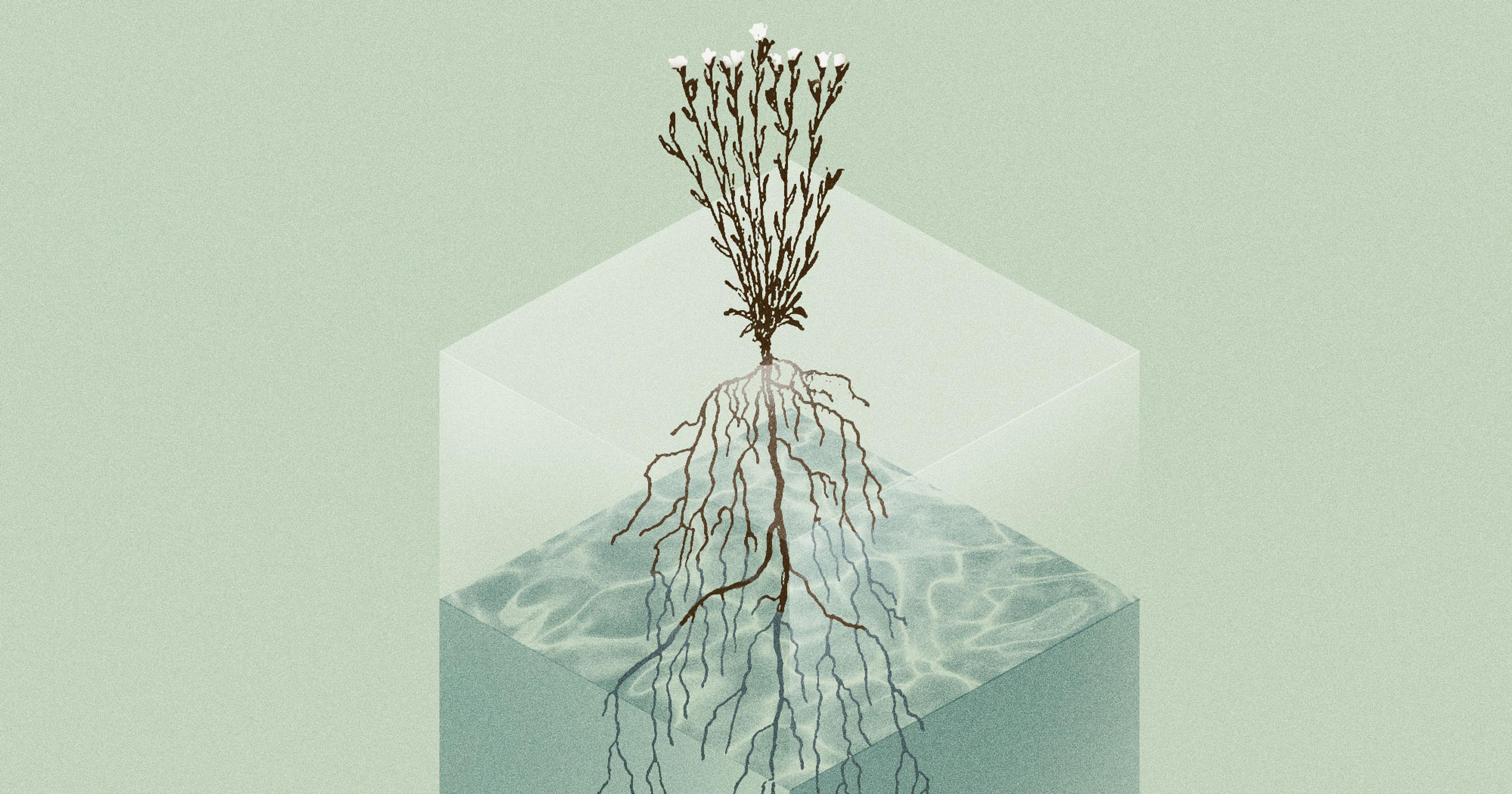

“Most of the existing yield and crop models that are available today that we use in agriculture assume that we have a full light spectrum,” said Abou Najm. By contrast, their model lets researchers input different light spectra, the visible energy-intensive wavelengths we see as colors, and estimates critical factors like transpiration, carbon assimilation, stomatal opening, and water-use efficiency.

The model draws from existing, published research on hydroponics and indoor agriculture, applying it to an arid California agricultural climate. While it doesn’t estimate exact yields, it does confirm that red lights — which have longer, less energy-intensive wavelengths — are more efficient for crop growth, while solar generation benefits more from blue lights, which have shorter wavelengths and greater energy.

Eventually, Abou Najm wants the model to help translucent solar panels take advantage of blue light for energy production and shine red light on crops for optimized growth. The work builds on earlier data supporting an agrivoltaic future, such as a 2013 study published by French researchers, who found that crops under solar panels grew at a similar rate with or without solar panels overhead, and studies on shading plants to prevent sun scalding.

“This will be transformative; I call it the second generation of agrivoltaics.”

To test the model in the field, Abou Najm began a “very small, focused experiment” last summer using tomato plants; he is currently analyzing that data and intends to publish the results this year. More species-specific data on plant responses to different light treatments is needed to confirm the model, and this summer, he and his team will conduct further experiments to see how much natural sunlight reaches crops grown under opaque panels.

“What we’re hoping for is that our data will inspire a newer generation of those solar panels that will also become mainstream that you can buy and install,” said Abou Najm. “That will be transformative; I call this the second generation of agrivoltaics.”

To actually filter the different light spectra in an agrivoltaic array, Abou Najm envisions translucent panels would need to be manufactured to optimize solar power generation and the development of specific crops. The U.S. Department of Energy notes that the part of a solar panel that converts solar radiation into heat can be color-adjusted in a newer technology called organic photovoltaic cells, which can be used on building facades — but at the moment, there isn’t a wide commercial availability of such sheer panels.

Sheer are currently around three times more expensive than traditional, opaque panels, according to Ian Skor, co-founder and chief executive officer of Sandbox Solar, a solar power developer based in Fort Collins, Colorado.

That said, solar panels that aren’t completely opaque could benefit crop yields even without filtered lights, according to Skor. His company is piloting the crop yield impact of solar panels that are about 40 percent transparent with researchers at Colorado State University’s Agricultural Research Development Education Center.

There isn’t enough of a current need to build enough semi-transparent solar panels to make them less expensive.

Their research found that “many crops respond very well to partial shade conditions without hindering growth,” according to the project’s profile on AgriSolar Clearinghouse.

“Since then, we’ve been conducting studies every year … starting out with specialty crops the first year like tomatoes, cilantro, peppers, and a couple other leafy greens,” explained Skor. The team found “only a minor reduction in yields” underneath the semi-transparent panels, which Skor said are typically less than 8% transparent depending on the manufacturer. With 40% transparent solar panels, “there was actually an increase in yield.”

Even with promising yield results, Skor said there isn’t enough of a current need to build enough solar panels with different levels of opacity to make them less expensive. Additionally, he said, it can cost tens of thousands of dollars for testing certifications of new electrical products to be approved in the U.S.

The feasibility of the panel technology becoming commercially viable is one question; whether farmers will embrace agrivoltaics is a separate issue. “I had a problem figuring out if solar was actually going to be a good deal,” said Colorado corn and soybean farmer Thomas Wishall.

While “higher yield is the language that farmers speak,” getting them on board for agrivoltaics projects is nonetheless “tricky” because of the questions around what the business model looks like for both solar developers and farmers, said agrivoltaics consultant Alexis Pascaris, founding director of AgriSolar Consulting.

Overstating the value of currently available information would damage community trust.

“As the farmer, do I own this system? Do I own the rights to all of the sale of the crops? Do I care about an increased yield, or is the developer gonna take a share of those profits?” said Pascaris. “Those are the complexities being worked out in real time right now.”

In her experience, one of the main drivers for farmers adopting agrivoltaics is the revenue diversification. But even for some economically driven farmers, it’s hard to embrace such an endeavor when it’s still unclear whether they’ll make enough money to justify the effort, she said.

For that reason, Pascaris said it’s vital to ensure farmers feel empowered to make informed decisions that secure their farms for long-term profitability. She’s quick to note that with any research that specifically ties increased yields to the use of different light spectra through solar panels, there needs to be “a lot more data validation before we bring those claims in front of agricultural communities“ as the industry trudges through this “touchy phase of deployment.”

Abou Najm and Camporese acknowledge in their study that more research is needed to “assess which crops and climates are more suitable” for optimal food, water, and resource use. So overstating the value of currently available information would damage community trust, Pascaris adds.

“I don’t want us to be telling a Michigan bean farmer that he’s going to double his beans by doing it under solar panels, but I will want to sell an Arizona tomato farmer on that concept,” said Pascaris.