At the world’s largest cattle-feeding company, early disease detection couldn’t be more important. They’re still working out the details.

Five Rivers Cattle Feeding LLC is the world’s largest cattle-feeding company, employing hundreds of workers in 13 feedlots scattered across six states. Veterinarians, managers, health staff, and barn employees support the health and welfare of nearly 865,000 cattle.

These employees identify and treat respiratory diseases, pneumonia, viral and bacterial infections, rumen disruptions, lameness, and a host of other health-related maladies, injuries, and defects. They insert rectal thermometers, inject antibiotics, deliver oral drenches, and complete minor and major medical procedures to care for the sick.

Alongside this, dozens of riders comb through countless pens, scanning for a nearly never-ending, committed-to-memory list of symptoms and clinical signs including every consistency and variation of bodily discharges and fluids, irregular sounds, surprising behaviors, awkward gaits, funky smells, and much more. All this is accomplished from the back of a horse, often in extreme heat or cold, gale force winds, sheeting rain, and/or howling blizzards.

Even when deemed successful in their roles, too many animals die; cattle are prey creatures and use every shred of willpower to hide sickness until they’re no longer able. No matter how experienced and knowledgeable, even the best pen riders are mere mortals. They cannot see what isn’t yet there to see.

Five Rivers personnel aren’t unique or unusual in their abilities, but an example of what occurs each day across the cattle feeding industry. Veterinarians assess and prescribe, barn staff probe and record, and pen checkers ride and inspect, each mirroring various industry approaches to animal health. Five Rivers, as the largest feedyard in the country, is representative of the industry’s tech-driven push toward predicting cattle diseases earlier and more efficiently.

Tech Languishing in the Shadows

Technology has created superior vaccines, more efficient antimicrobials, and improved treatment deliveries, but identifying cattle illness before clinical signs appear has remained an industry challenge.

A ride amongst the pens at Five Rivers confirms evidence of tech-based aspirations. Currently trialed and functioning hardware hums quietly beside unused, previously tested gadgets deemed ineffective or impractical. Sporadically mounted on alleyways, light posts, gates, and bunk rails, they cast a shadow of proof on the efforts made.

“Being in agriculture has a way of wearing us down, as much of what we play a role in is often out of our control.”

“Seeing this evidence, it’s obviously a work in progress,” said Five Rivers’ head veterinarian, Josh Szasz. “Being in agriculture has a way of wearing us down, as much of what we play a role in is often out of our control. Early disease detection technology is no different, but this ... doesn’t stop us from returning to the table when something new shows promise.”

Five Rivers focuses on early disease detection innovations. If these advancements could ever crest the figurative hilltop, the cowboys might be able to ride into previously uncharted territory, identifying sick animals for treatment days before clinical signs surface.

“Our motivation toward using these early disease detection tools is to deliver fewer antibiotics and to use them more judiciously. We want to do our part in curbing antimicrobial resistance too,” Szasz said. “These kinds of improvements are good things.”

Look at Those Handsome Muzzles

Of course, if technology startups wish to showcase their capabilities, the largest feedyard in the world is the ideal place to do it. To this end, Five Rivers Cattle Feeding hosts periodic competitions with many disease detection startups exhibiting their offerings to capture the feedlot’s attention.

MyAniML, a Kansas City-based animal health technology company, attended one of these competitions, propelling themselves onto the feedyard’s radar. Their technology uses motion sensor cameras to photograph faces and, more specifically, muzzles. Facial recognition identifies individuals, and AI breaks down video and picture data, assessing muzzle distinctions to predict the onset of illness.

“Each muzzle is like a fingerprint,” said Shekhar Gupta, MyAniML’s founder and CEO. “They go through tiny changes as health status fluctuates. By studying these minute differences in a muzzle’s ridges, we can predict health events 2 to 3 days before noticeable symptoms occur.”

Feedlot cattle generally live close together; disease transmission is a major concern. But Gupta believes facial recognition and muzzle analysis will help identify and isolate sick individuals earlier, saving money on treatment costs and reducing transmission risks.

Turn Up the Lights

Five Rivers has hosted several smart ear tag startups hoping to catch the operation’s attention with their unique product capabilities.

HerdDogg is a technology company that operates like a benign Big Brother, continuously watching over animal health from afar. Its Bluetooth-capable system uses accelerometers and sensor-equipped ear tags to detect minute temperature and movement changes even the most experienced handlers can miss. These smart tags collect data and upload it to the cloud, where algorithms correlate it to individual health status. Alerts of potential sickness or injury are delivered through text messages or emails.

“We’ve improved our health algorithms to be more customizable to each operation,” said HerdDogg CEO Andrew Uden. “Our system now allows users to remotely activate ultra-bright green LED lights on the smart ear tags of sick animals making it easy to identify them.”

Uden says their enhanced capabilities have cut false positives across the board without sacrificing detection of true positives. Their timing has also improved with shorter intervals between alerts and less time needed to ‘train’ the algorithms on new cattle or properties.

Currently, Five Rivers hasn’t committed to any smart ear tag startups, although they remain interested in their capabilities.

A Deep Breath to Assess

Isomark Health, a Wisconsin-based animal health company, has developed a non-invasive technology to monitor disease status by measuring and analyzing isotopic biomarkers in exhaled breath samples.

While they haven’t taken part in any of Five River’s events, they are currently attempting to advance their innovation further into beef markets.

Isomark’s patented breath analysis system provides sickness notifications one to two days before clinical signs appear. In ongoing, internal, dairy-based trials, the technology identified ketosis and milk production issues three to five days ahead of conventional methods. The company is currently enhancing its algorithms for infections and adding identifications for other metabolic diseases.

“Isomark is optimizing cattle management by observing health, metabolic status, and methane emissions,” said CEO and founder Fariba Assadi-Porter.

The company’s next goal is to place the device on more dairies and feedyards, screen more animals, and increase awareness while developing a smaller footprint for the next generation of their device.

Other Innovations

Many other start-ups have generated feedyard interest.

One biotechnology company developed a rapid farm-based blood test for immune health status. Smart rumen bolus devices claim to detect sickness up to 5 days before symptoms appear. Computer vision analyzes movements and behavior to identify illness, while internet-connected smart collars detect irregular patterns, including H5N1 avian influenza. Another start-up uses leg tags that monitor motion and gait for health issues. And out-of-the-box software programs are interpreting vocalizations to diagnose sickness.

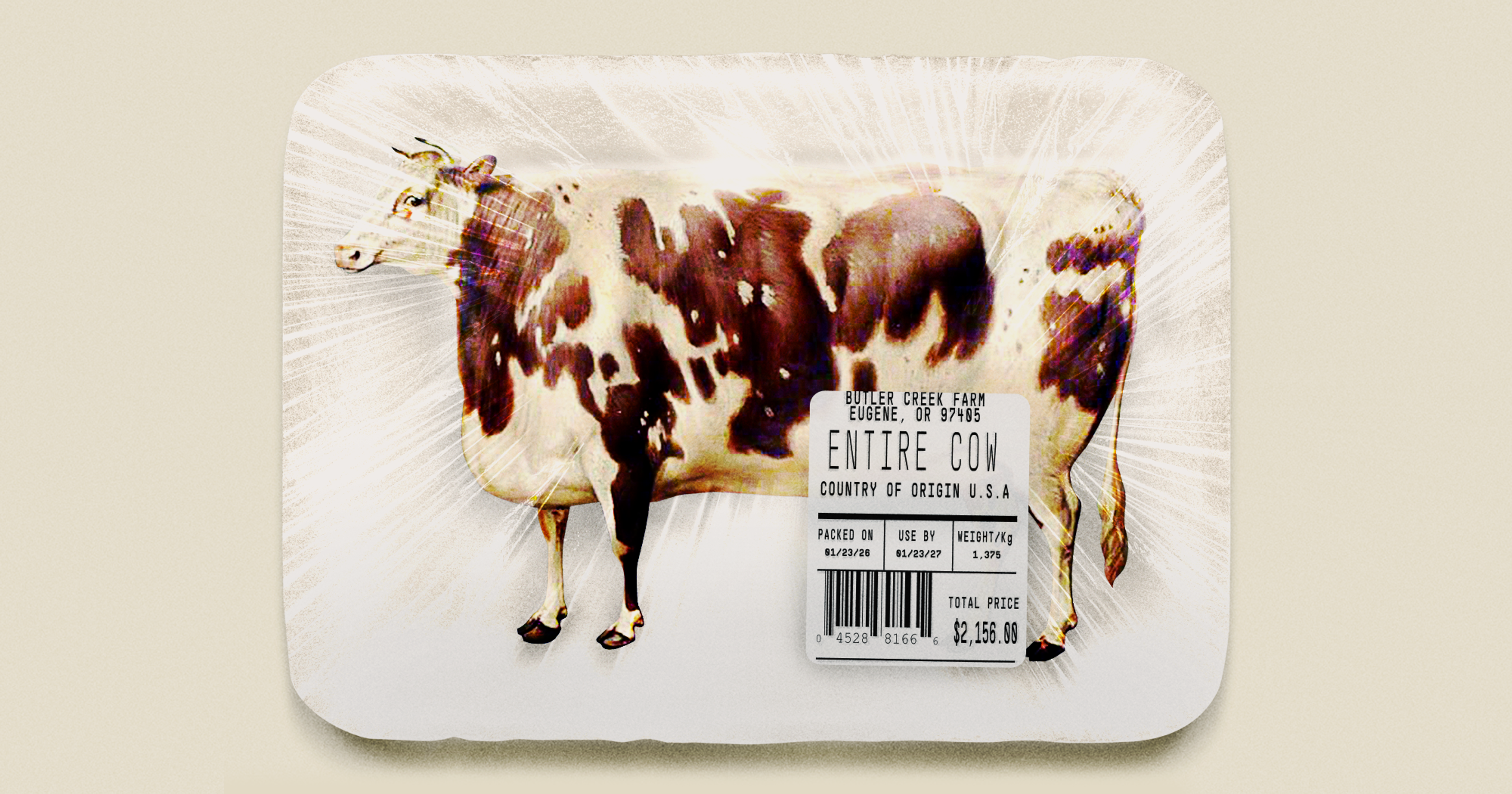

It remains to be seen if any of these innovations will “pass go” on the way to Five River’s ground floor. For Dr. Szasz, this speed of commerce always represents the massive elephant in the room. It’s where he gauges promise.

“If our motivation to pursue innovations is sidelined by cost or speed of commerce not matching our reality, it tends to go away.”

“If we have to adapt our handling chutes or hire an extra person to run a device, it tips the scales,” he said. “We continue to show interest, but If our motivation to pursue innovations is sidelined by cost or speed of commerce not matching our reality, it tends to go away.”

“Early disease detection technologies are promising; they really are,” Szasz added. “[But] while this potential is getting closer, some truths still make us hesitant.”

He’s tested many innovations but continues to find most are still too expensive, don’t work well in the realities of production, have cumbersome hardware, exhibit connectivity issues, or are simply too far off to be a genuine option.

Yet Szasz continues to be hopeful. “I’ve got to stay optimistic something positive will come along or an upgrade to something currently out there will be the answer,” he said. “Maybe the next pitch we hear will move the ball down the field. If it’s a break-even proposition and the right thing to do, we’ll do it. Even if we lose a little money or efficiency, and it’s the right thing to do, we’ll do it. And especially if an animal welfare breach occurs if we don’t do it, it’s a no-brainer. I’m optimistic. We’re on a slow march but at least we’re still moving.”