Bovine respiratory disease is deadly, costly — and famously difficult to detect. A new pilot study charged dogs with tracking down the elusive illness.

By some accounts, bovine respiratory disease (BRD) is both the deadliest and most costly issue affecting beef cattle today. It’s also quite prevalent, affecting upwards of 16% of cattle on feedlots.

“The No. 1 struggle I have in farming is BRD. I believe it’s the biggest problem in the beef industry,” Indiana farmer Aaron Holt told Drovers in 2020.

But for all its destructive capability, BRD detection and targeted treatment remains a significant challenge for clinicians. Though some futuristic technology has shown promise, they haven’t solved the issue yet. The reasons are varied — cattle are adept at hiding illness, testing can take multiple days, symptoms aren’t always visible, new tech is expensive — but the outcomes can be grim. And the favored approach of treating large swaths of cattle with preemptive antimicrobials has helped put antimicrobial resistance on the World Health Organization’s top 10 most pressing concerns.

Enter the hounds.

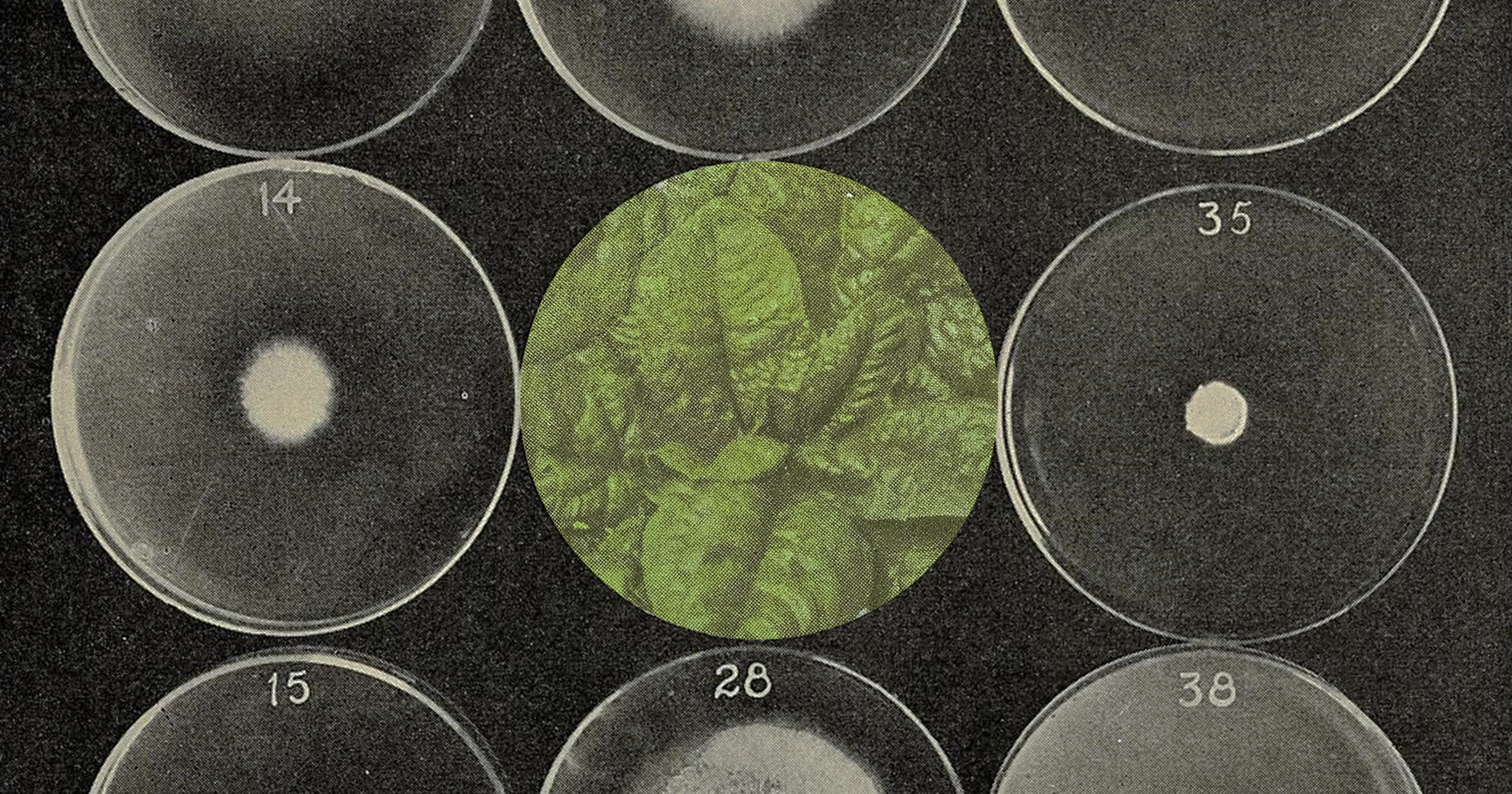

At Texas A&M University, a cross-discipline pilot study recently set out to discover whether working dogs, with their superior olfactory senses, could be used as early BRD detectors — just as other dogs have detected cancer or low blood sugar in diabetic humans. Using two hound dogs, Runnels and Cheaps, that were initially bred by the Texas Department of Justice for use in correctional facilities, a team of researchers spent months training the pooches to sniff out infected nasal swabs. It was a small study, meant to determine if more research is warranted.

“Because of the predator-prey dynamic that happens between humans and cattle, cattle are really good at masking when they don’t feel very well,” said Courtney Daigle, animal welfare specialist at Texas A&M, explaining what prompted the pilot study. “But cattle also communicate a lot through olfaction. And dogs have an excellent sense of smell, and we have a pretty good means of communicating with dogs.”

It’s a fairly straightforward hypothesis, but testing it out proved to be an elaborate and novel procedure (a variation on training used with other disease- or bomb-sniffing dogs). It started with three Christmas tree stands, placing food in one of them — an easy starter test. Next they switched to a novel artificial scent (the team used banana); the dogs were trained to sniff it out in increasingly faint levels on one of the stands. Finally they moved to nasal swabs which they’d kept in a deep freeze for months, from both cattle believed to be healthy (more on that below!) and BRD-infected cattle.

After many trials comparing one particular set of clean and infected swabs, the researchers were able to get up to 82% accuracy with one dog, and 65% with the other. But despite this eventual success rate with a specific set of samples, the dogs didn’t fare nearly as well when given only two chances to distinguish between a BRD-infected swab and a clean one.

“One of [the dogs] was 45% accurate, and one of them was 39% accurate in picking out the right one, where what we’d see by chance is 33%,” said Aiden Juge, a doctoral student who helped carry out the experiment. “So they were slightly better than chance but not great.”

That said, Juge noted that the experiment may have been marred by some of the very difficulties it was setting out to address — namely, clinical detection of BRD remains imperfect. “Since it is so hard to visually identify those cattle that are sick, it’s quite possible that some of the ones that we labeled as healthy might actually have been sick to a certain extent and not showing symptoms,” he said. “Which means that it’s possible there wasn’t really a clear, healthy reference to train the dogs.”

“From a veterinary perspective, why would I medicate an animal that doesn’t need an antimicrobial?”

Additionally, BRD isn’t caused by one specific type of bacteria; Daigle noted that “there are dozens of viruses and bacteria involved and different sorts of concentrations and combinations.” Some are more common causes than others, but Daigle said they didn’t want to pigeonhole one particular pathogen over another. Rather, the infected swabs weren’t traced back to specific causes; they simply came from cattle with clear visual signs of BRD — an imprecise art.

The team is working on refining these variables and others — mixing samples from bulls and castrated steer may have added a hormonal variable to the results as well — but remain hopeful that it’s a fruitful scientific pursuit. John Richeson, a BRD expert who also worked on the study, said the primary goal would be to provide more targeted antimicrobials to feedlot cattle.

“Right now we determine whether cattle need an antimicrobial on a mass basis when they arrive at a feedlot, depending on the history of the animals, how they were purchased, different factors that determine the risk of a group,” said Richeson. “The hope is that a dog could allow us to go within a higher risk group and find the individuals that really need antimicrobials for control.”

And of course, reducing the broad use of antimicrobials and antibiotics is a shared goal of much of the veterinary profession. Ron Tessman, principal research scientist at the animal health company Elanco, said he was excited to hear about this potential new tool in BRD detection and antimicrobial reduction.

“From a veterinary perspective, why would I [medicate] an animal that doesn’t need an antimicrobial, with the potential that there may be some adverse consequences to that?” he asked. “Not to mention it doesn’t make sense from a pure economic perspective. I welcome anything that could make us more accurate at diagnosing the animals that actually need antibiotics.”