There’s a common belief among ranchers that if you throw a livestock guardian dog into a pasture, instinct will kick in and they’ll know what to do. That’s rarely true.

By the time Goose, a fluffy white Great Pyrenees puppy, had turned 10 months old, he had killed nine cats, three chickens, and had gotten into serious scuffles with other livestock guard dogs on the ranch where he had been living.

This behavior was a bad omen for the job he had been bred to do — protecting farm animals from predator attacks.

Goose had been passed from place to place before he wandered over to Amy and Danny Singleton’s hobby farm just outside of College Station, Texas. Rather than reclaim him, Goose’s last owner decided it would be best to surrender the aggressive roamer to the Singletons. “He kept running off and ended up at our little farm,” said Danny Singleton. “I fell in love with him on day one.”

Livestock guardians are one of the best tools to manage predators in a nonlethal manner and are often hailed as a quick fix to livestock depredation. But sometimes the animals — which can also include donkeys, llamas, guinea hens, and others — can turn on the animals they’re supposed to protect. Modern farmers are increasingly turning to livestock guardian specialty trainers and Facebook groups for help in managing these potentially deadly situations.

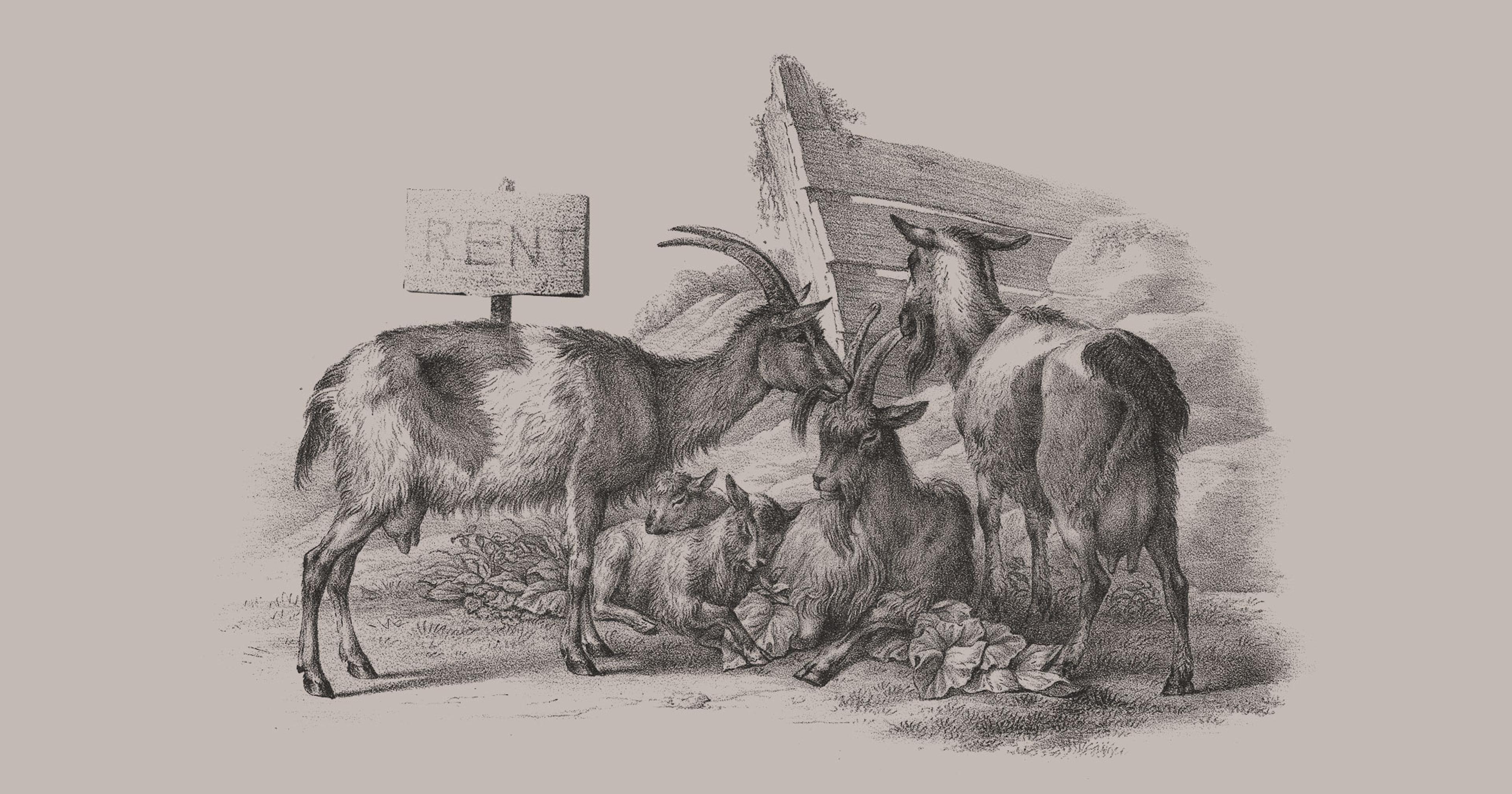

Predators killing livestock, specifically smaller animals like sheep and goats, is a huge, expensive issue across the United States. In 2019 alone, 71,440 sheep and 155,470 lambs were lost to predators according to the USDA, at a loss of nearly $30 million. Around half of those deaths were due to coyotes, which livestock guardians, especially dogs, are particularly effective at defending against.

Since dogs — which have been used by shepherds in Europe and Asia for thousands of years — are the most common livestock guardians, they tend to have the most problems. (Though both donkeys and llamas have also been known to harass, injure, or kill livestock too.)

There’s a common belief among ranchers that if you throw a livestock guardian dog (LGD) into a pasture, instinct will kick in and they’ll know what to do. That’s rarely true. Like all working animals, the right breed needs to be used for the right situation, and they need proper socialization and training to learn their job.

“In this country, 30 percent of livestock guardian dogs fail and most of those are euthanized,” said Cindy Benson, an Oregon-based certified trainer and Maremma-Abruzzese Sheepdog breeder. “Almost all of that is learned behavior due to management decisions or the owner.”

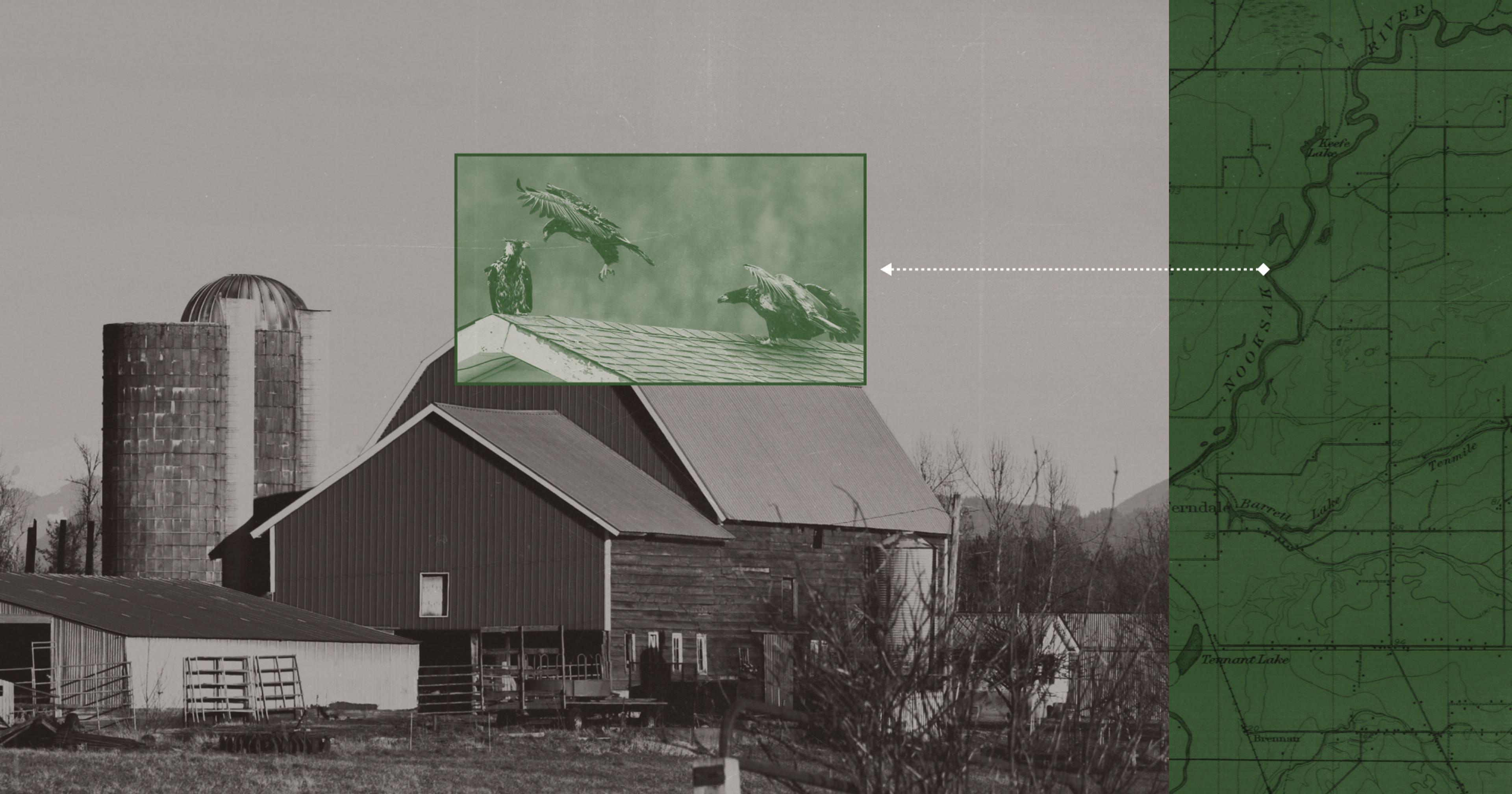

When not handled properly, these giant canines can become overly aggressive toward humans, livestock, working dogs, and other canines who live on their property, or non-predatory wildlife. Some LGDs also are known to roam far beyond the borders of their property, leaving their stock unattended and open to predation.

Like all working animals, livestock guardians need proper socialization and training to learn their job.

Though Goose’s roaming and reactivity issues are not uncommon, his start in life was anything but average. At a very young age, he was turned out with chickens without supervision. When he killed them, he was beaten and shot with a shotgun. At one point, he was covered in motor oil, Singleton assumes due to an old cowboy’s tale that it cures mange. (It does not.) Eventually, one of the men who owned him gave up on the aversive “training” techniques they had been using and dropped him off at a rescue.

In one sense, Goose was lucky. There are plenty of cases where these dogs — breeds such as Great Pyrenees, Kuvasz, Akbash, and Anatolian Shepherds — end up getting put down by their owners for perceived aggression.

This is especially true when guardian dogs are found eating dead lambs, kids (the goat kind), or other animals. Many ranchers who come upon these grisly scenes believe the dog is responsible for the death and, while that can be true, many of these dogs do have the instinct to clean up anything that might attract scavengers or predators to their territory including fluids like after birth.

“People assume that a dog is killing and they might need to shoot that dog — that isn’t necessarily true,” said Bill Costanzo, researcher for Texas A&M AgriLife Research livestock guardian dogs program. “There have maybe been four times [out of many calls] when a rancher actually saw a livestock guardian dog chase and grab a lamb or kid and kill it.”

Most of the time these dogs — which were selectively bred with a minimal prey drive — hurt another animal, it’s due to teenage rowdiness, said Costanzo, who oversees the only program dedicated to the study of livestock guardian dogs in the United States. Where most working dogs are mature enough to start learning the basics of their job at six months to one-year-old, livestock guardian breeds are about six months behind in their maturation process. Most issues with animal aggression show up between eight to 18 months of age.

Photo by Amy Williamson

·Goose: Trying to be a good boy.

“During that time, a lot of dogs will chase sheep, chew on kids‘ ears or tails and do a bunch of bad things adolescent dogs do,” said Costanzo. “75 percent of the phone calls I get are about adolescent issues.”

To ensure success, producers should expect to offer focused management to livestock guardian dogs until they reach two years of age. This could mean using game cameras to make sure dogs aren’t roughhousing with other animals and herd leaders aren’t picking on the dogs — which is a big reason these dogs react and fight back. It’s also important to ensure dogs are properly bonding with their flock. They need to be supervised while they are being socialized to things like adding new members to the herd and, especially, lambing and kidding — which can be very confusing for an inexperienced pup. “All of a sudden their stock is distressed and this raises the concern of the dog, like what’s wrong, and then a bloody lump falls out of it,” said Tarma Shena, a Central Maine-based trainer, writer, and breeder of Anatolian Shepherds. “The dog has no experience with what’s going on.”

Tarma and other trainers like Benson advocate for using safety lines when introducing puppies to these kinds of novel situations to give them freedom to make good decisions while enabling handlers to protect all animals from potential overexcitement or stress.

The goal of training is to help the dogs to bond with the flock and their shepherd, so they can learn how to effectively do their job. When that bond isn’t present, issues are more likely to arise, like learned aggression and — one of the more common problems with livestock guardians — wandering. “We believe the main cause of roaming, or one main cause, is because dogs are not properly bonded to livestock as a puppy,” says Costanzo.

Goose may not have had that prime bonding time with stock in his early days, but the Singletons have been working hard with a positive reinforcement trainer to solidify their bond with him and safely socialize him with their horses, cattle, goat — they’re leaning heavily on a kennel and lots of leash work. Within a couple of months, Goose has learned important commands, such as “Leave it.” So, when he has gotten overly excited by their rowdy Nigerian dwarf goat, he now knows he’s expected to control that impulse. Though the couple has no plans to leave him unsupervised around their animals anytime soon, they do anticipate he will mature into a good working dog who will be able to keep their cattle and high-value horses safe from harassing coyotes and other threats.

“I totally intend to let him do his job,” said Amy Singleton. “I believe these are some of the most misunderstood dogs on the planet — they’re getting labeled as bad dogs but it’s really just bad training.”