Turbulent meat prices could push Americans to buy a year’s worth of beef at a time — a huge shift to how we think about meat.

Lauren Bailey answered the phone just a few hours after she’d picked up her annual quarter cow. The butchers at her local shop in Eugene, Oregon, are always slammed, and that November day was no different. She waited as six workers ran around, cutting and processing meat. Eventually they cashed her out (around $900) and loaded up her car with roughly 125 pounds of frozen beef — enough to last Bailey and her husband the entire year, if not longer.

She acknowledges that the upfront cost might deter many, as would the inflexibility in choosing which cuts you take home. (A quarter of beef only has so many ribeyes, for example.) But it’s much cheaper than if she bought meat throughout the year from the supermarket, she told Offrange. And the stockpile of protein gives her freedom.

“I grew up pretty poor,” she said over the phone. “But to know I have a freezer full of meat, that I have a year’s worth of meals, is really helpful.”

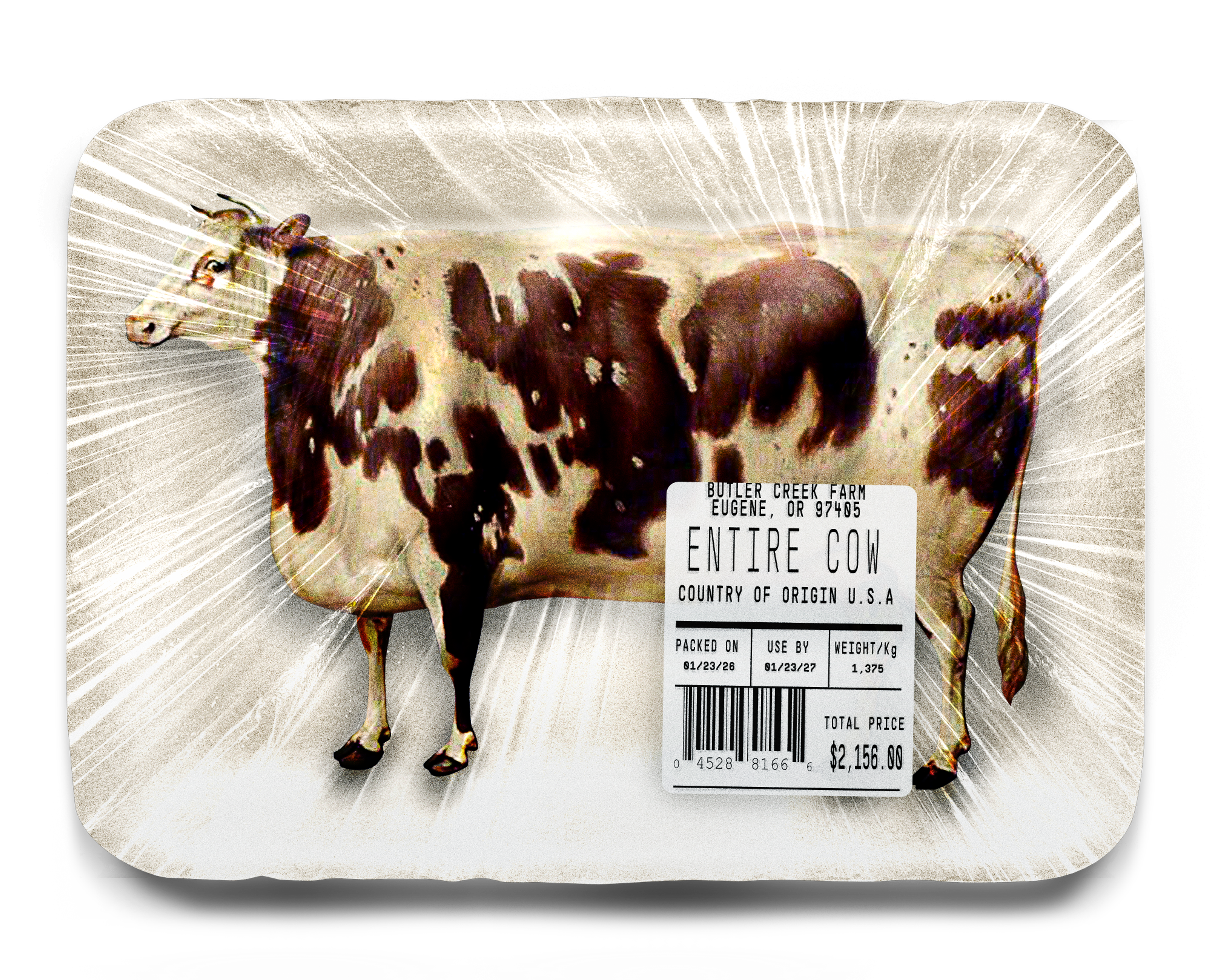

For the majority of U.S. meat-eaters today, this approach is foreign. Most consumers know their meat as the pre-portioned plastic-bound flesh lining rows of grocery store refrigerated shelves. But with increasing social, political, and economic instability, some are predicting more Americans will attempt to insulate their pantries and wallets by adopting Bailey’s style of purchasing: buying their meat in bulk directly from farmers.

Michele Thorne is one of those believers; she leads a nonprofit, the Good Meat Project, that’s committed to making more ethically produced meat accessible to the average American. Buying in bulk, she said, is a consumer- and farmer-friendly approach that skirts many of the pitfalls of the meat market today. Almost six years after pandemic disruptions laid bare the fragility of our food supply chains, meat remains especially unstable.

Beef prices are “near record levels,” according to the The New York Times, in part because drought-afflicted herds are shrinking. In November, the Trump administration green-lit low-tariff beef imports from Argentina, claiming it would lower beef prices in the U.S., but so far cattle ranchers say the move “hurts U.S. farmers,” according to CNN. Two major meat processing corporations have recently agreed to pay millions to settle a 2019 beef price-fixing lawsuit filed on behalf of consumers, according to NBC News. And meanwhile, record stagflation has sent grocery prices soaring, while millions of SNAP users’ benefits — wielded as political pawns during the recent government shutdown — were not guaranteed for a portion of this year, contributing to overall unease.

Amid this uncertainty, buying in bulk can be a balm. Bulk shoppers like Bailey pay one price per pound for everything, whereas the price per pound at supermarkets will have “such a huge range,” Thorne told Offrange. And it’s better for producers, too. “I enjoy supporting a local farm, because I know that my money is staying in the community, in the state,” she said. “It’s a money multiplier, it boosts the local food system.”

“The timing was right during Covid because people couldn’t get stuff at stores, people were searching for farms they could buy directly from.”

For Bailey, her “local” farm, Butler Creek, is actually about two hours away, closer to the Oregon coast. It’s managed by an old friend of hers, Nadja Sanders, who also lives in Eugene, and whose family has managed Butler Creek Farm for close to 150 years. About 25 years ago, Sanders introduced bulk purchasing options and cow-shares. Since then, the customer base has grown entirely by word of mouth, with the advent of the internet making it easier for people like Bailey to place orders.

Because of the farm’s remote location, Sanders has few options for butchers. She partners with a Eugene-based mobile butcher, 4-Star, which will typically slaughter about 13 cows for them, once a year, around October.

“We’re about as far as they wanna go,” Sanders told Offrange of 4-Star. “They’re super willing and super efficient,” though she caveated that their customer service isn’t always the … gentlest. Sometimes they can be a little “gruff,” she admitted, but only because they’re always busy. They’re so slammed, in fact, that Sanders has to make arrangements for her butcher dates at least a year in advance. When she spoke with Offrange, she had just set the butcher date for October 2026.

But 4-Star isn’t an outlier. This country’s butchering industry has been shrinking for the last half-century, stretching the remaining butchers to their limits. In her professional spheres, master meat-cutter and fifth generation butcher Kari Underly talks a lot about the “missing middle,” or the slow disappearance of the butcher trade. It’s a trend that’s been disastrous for farmers and ranchers, who rely on butchers to connect them to the consumer — and who make bulk purchasing from small, independent farms possible. For example, 4-Star handles the slaughtering, processing, and final point of purchase for Butler Creek customers like Bailey.

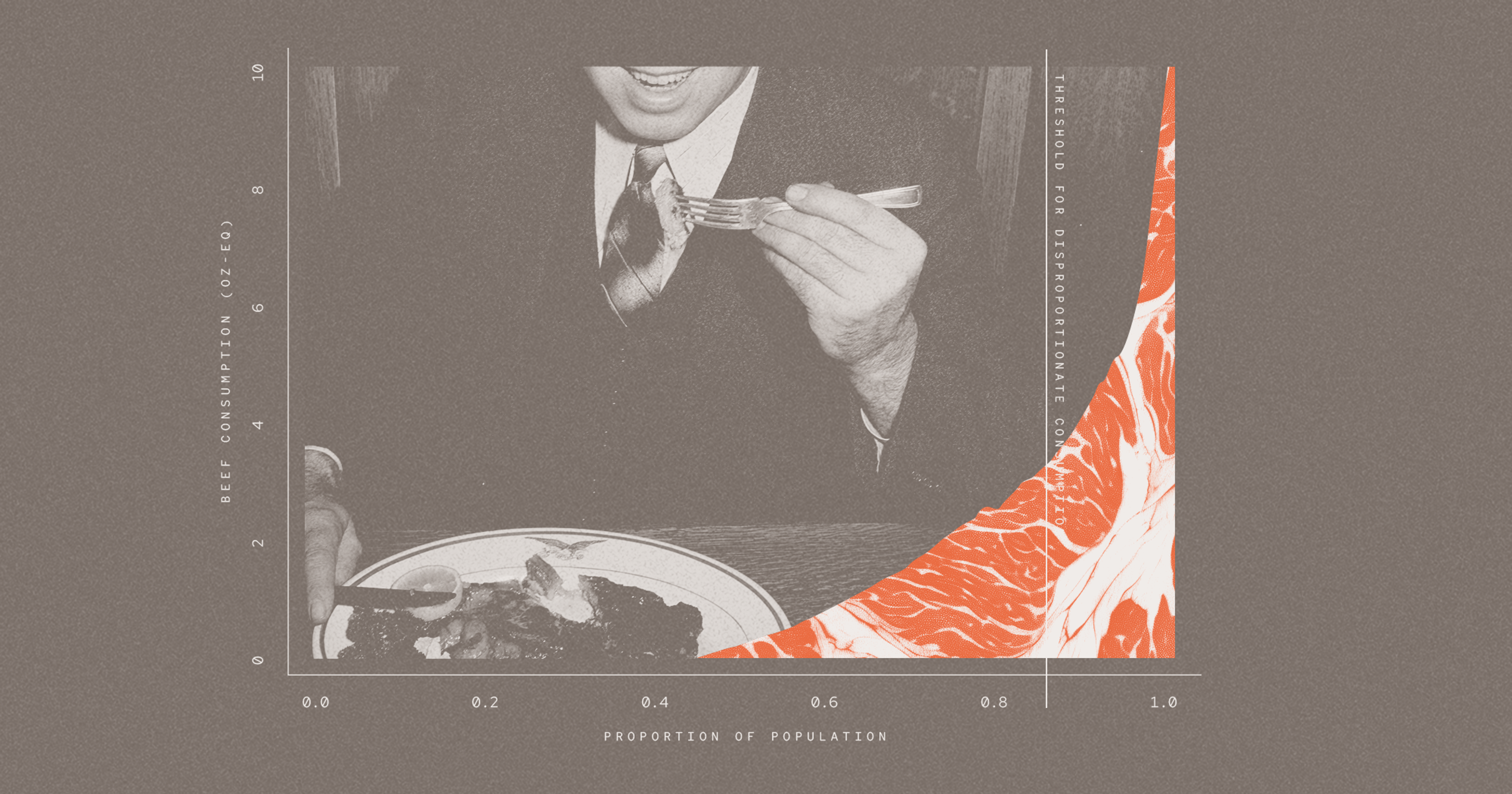

Small- and medium-sized meat processors are increasingly outcompeted by the “Big Four” meat companies — Tyson, Cargill, National Beef, and JBS Foods — which “dominate the industry and have the resources to control every aspect of the meat supply chain from animal feed to meat processing to distribution,” according to sustainability nonprofit The Lexicon. These corporations, which receive government subsidies, are able to process exponentially more animals at a time and undercut the costs of smaller producers, contributing to the loss of local butchers in communities around the country.

As the market value of skilled meat-cutters has declined, Underly said, so has the skilled labor pool — and companies have supplemented with undocumented immigrants who are frequently paid and treated worse. As of 2024, it was estimated that anywhere from 30 to 50 percent of meatpackers in the U.S. were undocumented, in some cases making poverty wages. This year’s tornado of ICE raids has led to the detention of many of those workers and pushed others into hiding, further decimating the meat processing workforce, Underly noted.

On the consumer side, the upfront cost is a deterrent, even if bulk-buying saves money over time.

She agreed with Thorne that a widespread transition of American families buying their meat in bulk directly from farmers would go a long way towards patching up the meat industry’s problems. But without more butchers helping to connect customers directly to their local farmers and ranchers, she said, it’s unlikely to gain ground with the average household.

For its part, the Good Meat Project is trying to address the access gap with a tool called the Good Meat Finder, which maps out farms that offer direct purchasing by region. They also hold marketing workshops and seminars for farmers and ranchers on how to transition to these types of direct sales.

Still, on the consumer side, the upfront cost is a deterrent, even if bulk-buying saves money over time. It’s an investment, Thorne said. She spends the whole year leading up to her annual half or whole cow purchase from Butler Creek Farm financially preparing. “Instead of paying $6,000 a year on meat, I’m reducing my costs by 25 or 30 percent every year by buying in bulk,” she said. “It’s a discipline like anything else you’re saving money for, like a house, or a car.”

“It really is a shift in purchasing decisions,” she said.

To dampen the sticker shock, some people go in on an order with other family members or neighbors — or sometimes even people they don’t know, not dissimilar to a CSA. Thorne, for example, split her first bulk purchase from Butler Creek with a stranger.

Resource-pooling might not come as naturally to those of us living relatively isolated 21st century lives. But, as Thorne pointed out, it was only two or three generations ago that it was more common — like in the 1970s, when her parents, aunts, and uncles all split meat boxes. They got “hundreds and hundreds of pounds of meat” that none of them would have been able to afford individually, she said.

But the average American has moved pretty far from that model. Community bonds are frayed, butchers are in short supply, and being precious about where your meat comes from is likely to come off as “elitist,” as Underly called it. And in order for bulk buying to catch on at a larger scale, consumers would need a serious meat re-education, too. Unlike at a typical grocery store, you can’t drop in at random and select the cuts you want. Buying a quarter of beef means you’re going to get all sorts of cuts — not just 50 pounds of steaks.

“It’s a discipline like anything else you’re saving money for, like a house, or a car. It really is a shift in purchasing decisions.”

At May Hill Farm in Campbellsport, Wisconsin, Carrie Stevens has gotten very good at managing customer expectations, though it’s yet another layer of labor on top of her already-demanding workload. Without a mobile butcher nearby, she and her husband haul their own animals to a handful of carefully vetted butchers in their region, who then handle the slaughter and processing. Stevens said next year they’re targeting 50 cows for butchering, and they’ve seen a steady increase in demand each year since the pandemic, when they began marketing meat directly to consumers. (They also raise pigs and chickens.)

“The timing was right during Covid because people couldn’t get stuff at stores, people were searching for farms they could buy directly from,” she told Offrange. And now with beef prices as volatile as they are, the bulk orders for quarter and half cows have been rolling in. But some of her customers need a lot of hand-holding.

“Buying in bulk is really different if you’re used to going to the grocery store,” Stevens said. “There’s only one tongue on a beef, only one heart, only one oxtail.” Some of her customers in the Milwaukee area ask for “like, 10 beef cheeks” at a time, apparently not grasping what it means to purchase a section of a steer.

But while some may feel deprived of their favorite cuts, Bailey happens to love that her annual quarter of beef lets her try meat she wouldn’t otherwise find at the local supermarket, like rump roasts, half briskets, and heart. Sure, she only gets a limited amount of steaks per order, but she chooses to look at the glass as half-full: Buying in bulk lets her experiment.

There are plenty of reasons the average family might not be able to buy meat the way Bailey and Thorne do it. Prohibitive upfront costs, the surrendering of total choice over cuts, the sheer weight of all that meat, and the challenge of actually storing it (between chest freezers, standup freezers, and fridge freezers, Thorne, for example, has five working freezers and one she plans on fixing up). But the experience of buying meat directly from a farmer instead of shrink-wrapped at the grocery store would seem to outweigh the negatives for many.

“We serve a lot of families, and people who maybe grew up with farming in their family,” Stevens said. “They say things like, ‘This pork tastes like the pork my grandma used to make.’ They really can tell the difference, and they appreciate that.”

Thorne believes that, if nothing else, buying directly from farmers and butchers goes a long way toward strengthening the overall community fabric. “There’s ways to get closer to your food, to get to know your butcher, to be in relationship with your farmers and local meat supply chain and meet the faces of the people who are working so hard to keep their product so quality,” she said. She’s befriended her local butcher, who gives her free bones for her dogs, and she’s known the folks at Butler Creek Farm for years.

Buying her meat this way just feels good, she said. “It’s like Christmas when I pick up my meat from my butcher.”