Beef meatpacking lines — unlike those for chicken and pork — have long resisted full automation. Physical AI is changing that.

An artificially intelligent robot with an orbital saw capable of speedily processing an 800-pound cow carcass can feel reminiscent of the Terminator movies — but we might just have to get used to it.

Like other agricultural sectors, the meatpacking industry is not an exception to the automating economy. While mainstream meats like poultry and pork have seen decades of increasing automation — alongside a simultaneous reduction in the labor force — the process of turning a side of beef into store-ready meats has resisted simpler robotics.

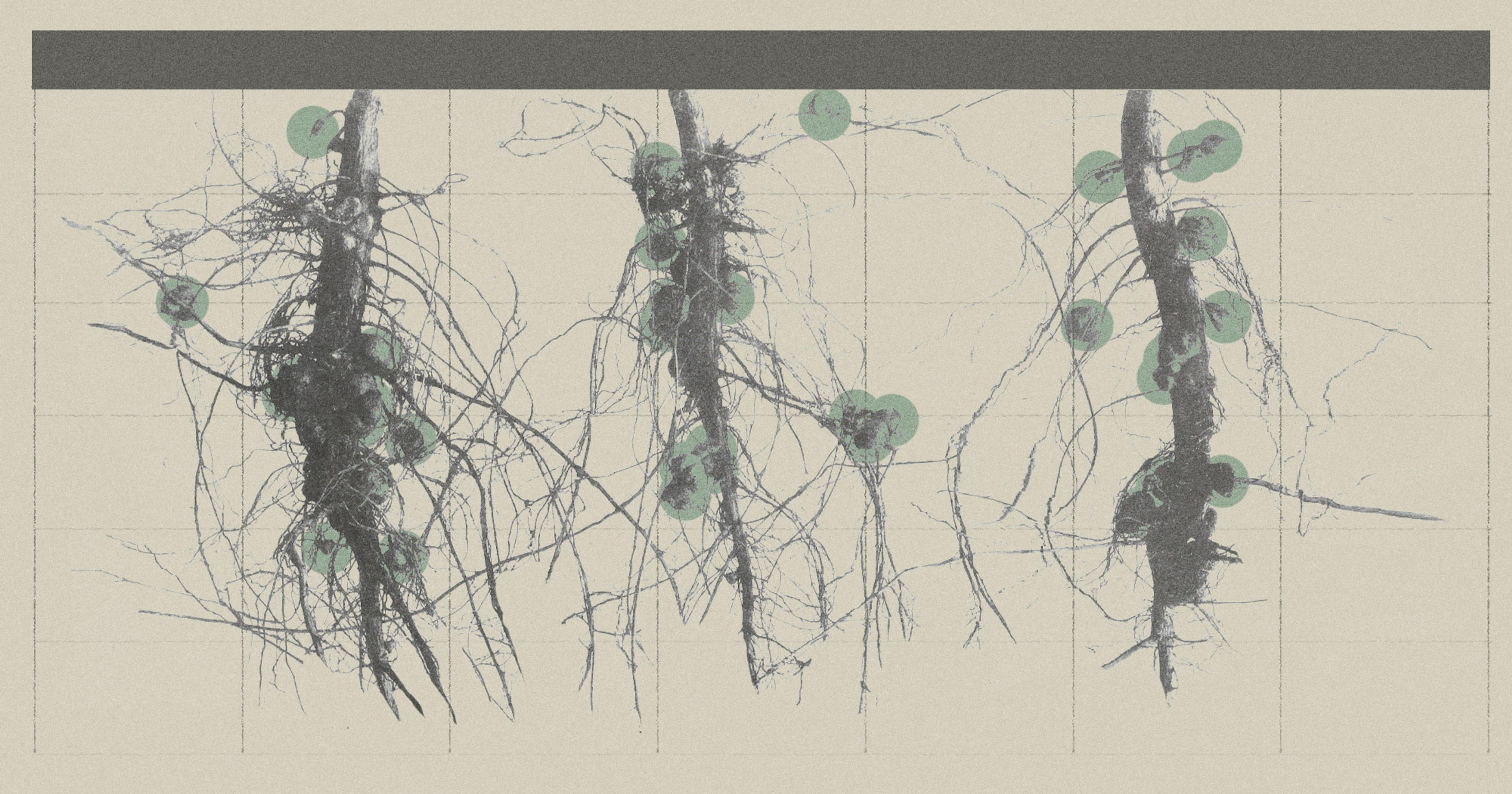

Unlike smaller-sized animals, two cattle from the same origin can have a weight difference on the scale of hundreds of pounds. Up until the AI boom, designing systems that could handle the variety of beef carcasses coming down a processing line had been out of reach. Meanwhile human labor is challenging, extremely physical, and rife with labor violations and shortages. But new AI-enabled technologies have brought the potential for sweeping changes to the industry.

Robots Dream of Electric Beef

Australia’s Intelligent Robotics is among the companies developing new meatpacking technology. In partnership with 3D machine vision lab PhotoNeo, the firm invented an AI-driven beef rig in 2023, and are now furthering a transformation that started with smaller-weight proteins like chicken and pork. And Scott, a New Zealand robotics company with clients in automotive, appliance, and healthcare, provides a mix of fully automated and manually operated mechanical systems for the butchering of lamb, beef, and poultry.

“The beef industry … is the protein area which has the least amount of automation so far. Part of the reason for that is the sheer variation in size that you get in beef, relative to [poultry or pork],“ said said Jonathan Cook, general manager of Intelligent Robotics. ”You might have a 160-pound side coming through one second, and then the next side of beef will be 800 pounds, and you’ll get everything in between.”

The step of the meatpacking process that Intelligent Robotics has developed technology for is known as “beef scribing,” or the breakdown of whole sides of cattle into more manageable sections that can be further cut into portions —think brisket, rib, or chuck — that can be sold to grocery stores. Typically, sides are hung on hooks and cut along the skeletal structure by employees using electric saws. The assembly-line work is physically demanding and repetitive.

In the plants that Intelligent Robotics supports, the large-scale cuts produced by the automated process are sent to be further butchered by laborers who perform tasks that require more dexterity. Still, Cook would like an entry point into automating technologies for producing these smaller, more complicated cuts “within the next couple of years.”

Whereas prior technology couldn’t accommodate the many challenges of butchering such a large and variable animal as a cow, AI possibly can. “Using a rules-based … system becomes very complex, [and] that’s the area where AI shines,” Cook said.

Labor on the Line

A 2024 cost-benefit analysis of the beef scribing technology at a KGF Kilcoy beef processing plant found that automated beef scribes were more accurate in their cuts than laborers across all cutting lines. With increased butcher accuracy, less meat left on carcass bones translates to higher repeated profits. And since these robots are fully autonomous, they obviously do not require the cost of labor.

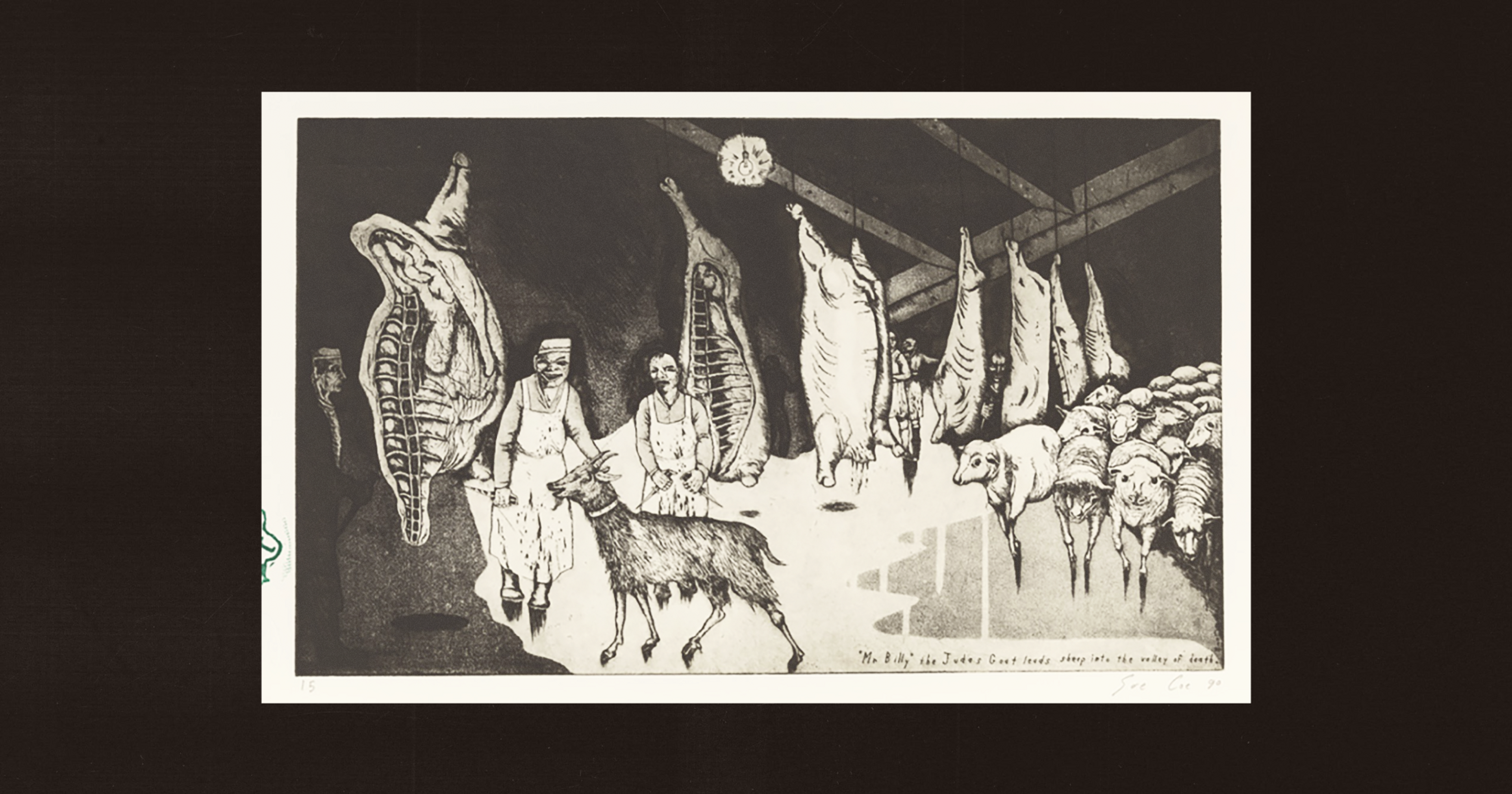

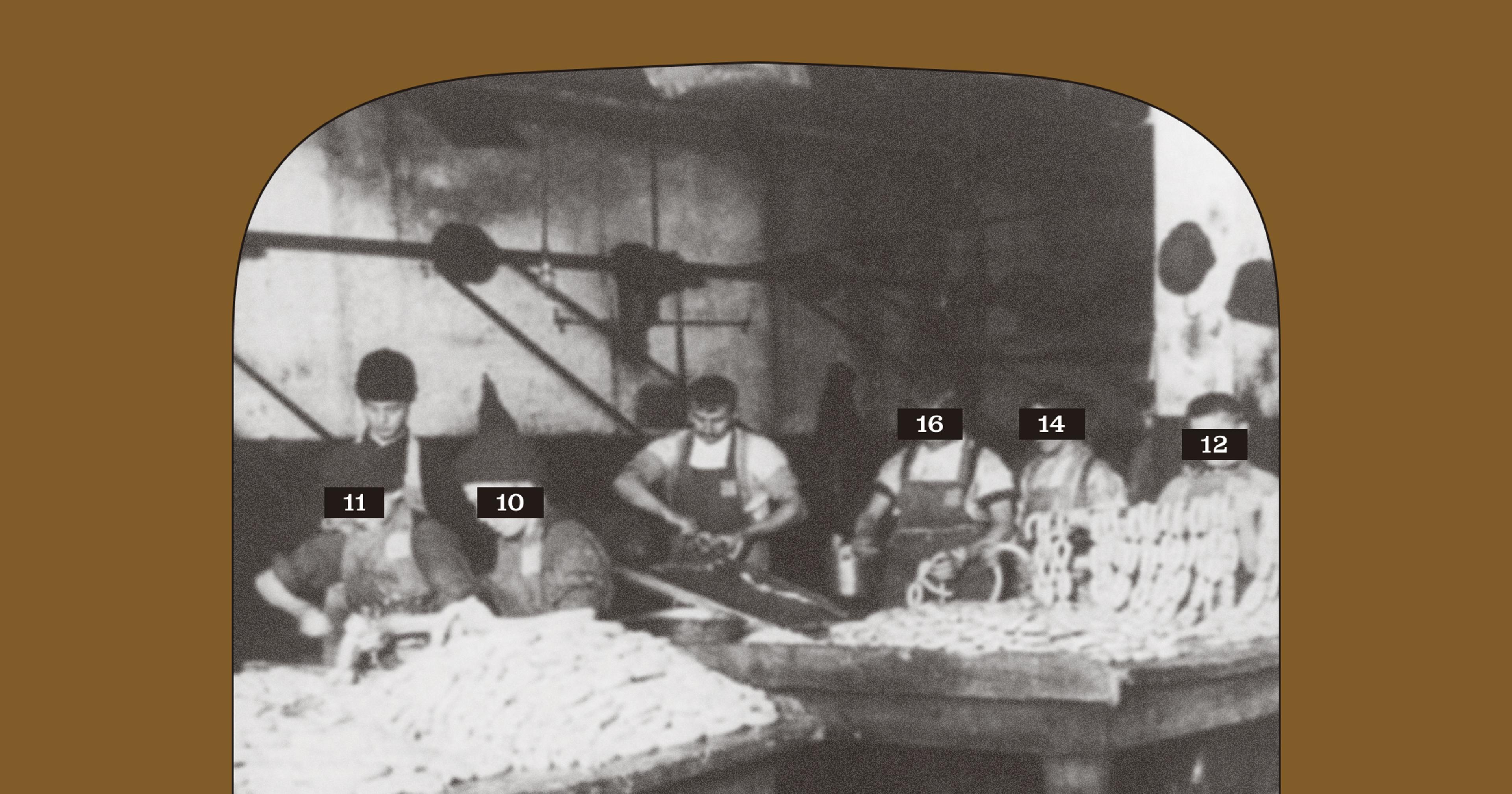

Robotics boosters suggest that the jobs aren’t all that desirable to begin with: Scribing is dangerous, tiresome, and extremely repetitive. Conditions may have improved significantly since The Jungle exposed America’s slaughterhouses in 1905, but that isn’t saying so much. Slaughterhouse workers were among the essential workers very negatively impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, with some of the worst workplace outbreaks in the United States. The job remains undesirable to many, and staffing remains an issue. In 2023, Iowa passed a law to allow 14-year-olds work in meatpacking plants, and recent waves of deportations have left fewer laborers for the industry.

Megan Elias, associate food studies professor at Boston University, noted that the initial turn towards mechanization at the beginning of the 1900s is to blame for many of these dangers in the meatpacking workplace. “In the days when you just had your local butcher chopping things up at his own pace, it was not dangerous at all,” Elias said. But as the United States urbanized, food producers moved farther away from food consumers.

In 1900, 40% of Americans were agricultural workers; now, about 1% are. The history of American agriculture is the history of automation, Elias remarked. “When people are rounded up and taken out of the country, nobody will save those positions because [they’re] difficult. And so that seems like a problem for AI … if nobody wants to make the potatoes, can AI do it?”

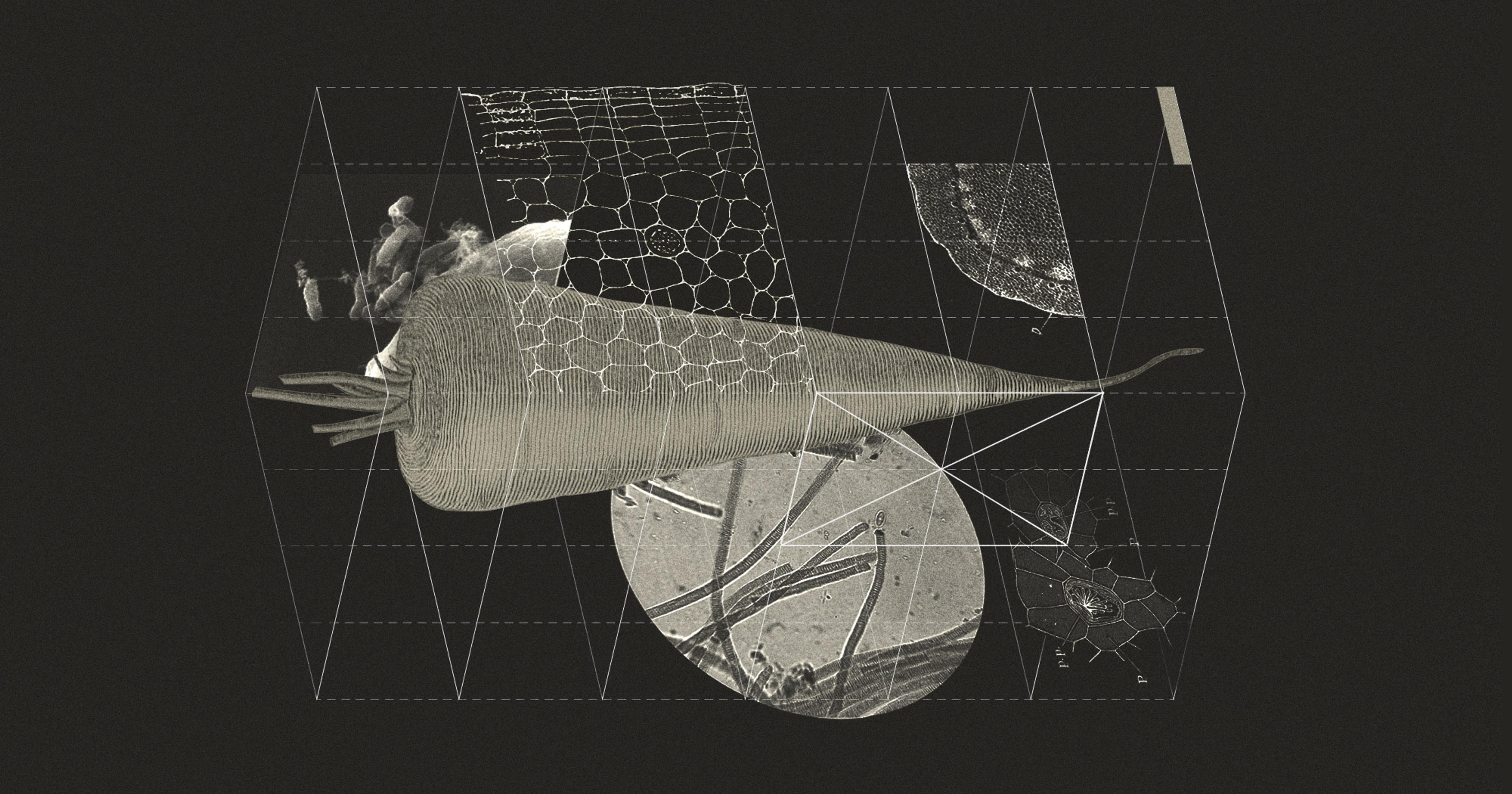

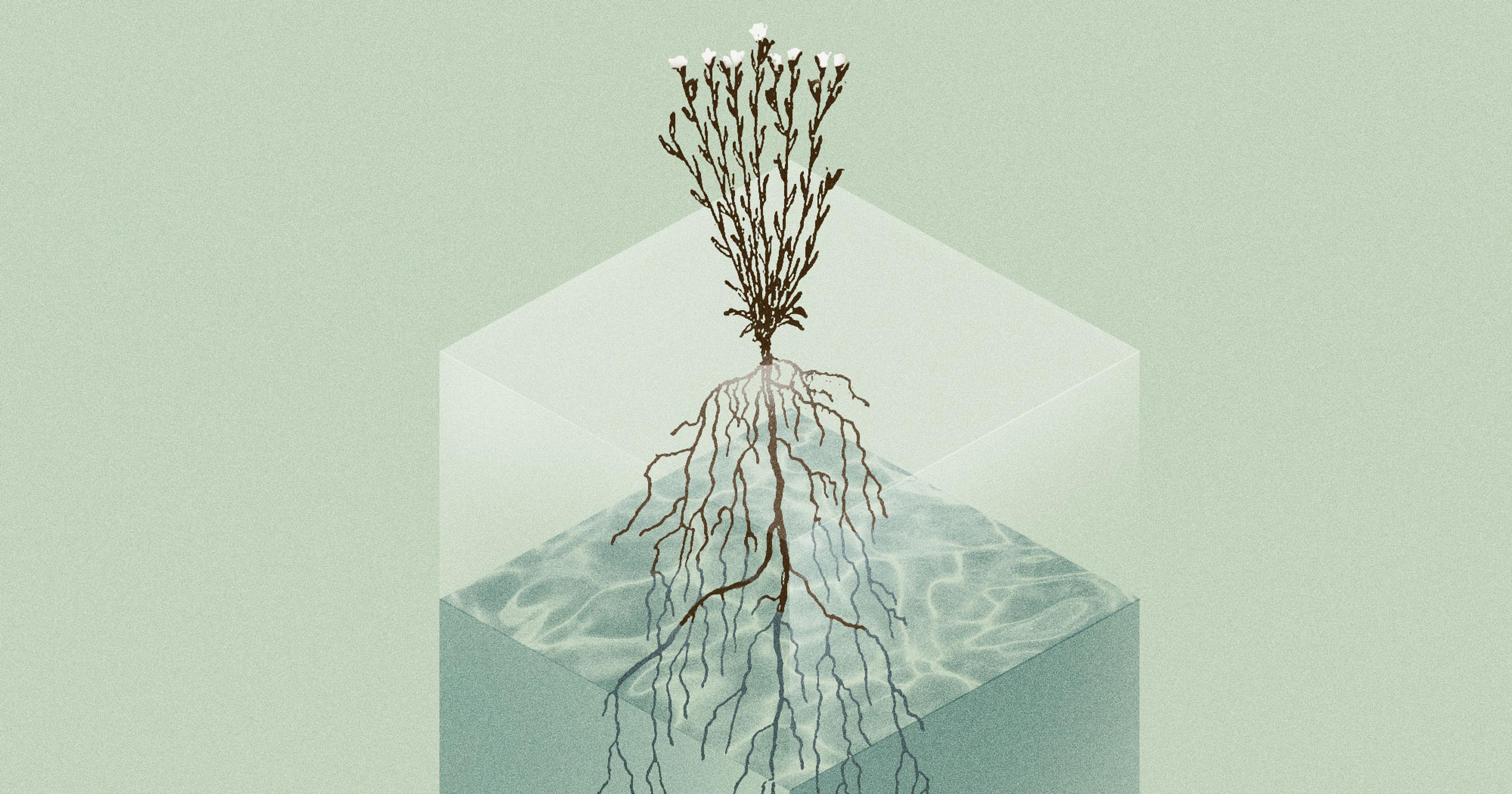

AI Gets Physical

The shift towards robotic beef meatpacking is part of the larger movement to implement “physical AI”: Think self-driving Waymos, humanoid Amazon workers, and unmanned surgery. Unlike a large language model like ChatGPT, physical AI utilizes a “digital twin” — a virtual model of a real-life object that is updated in real-time with input from motion imaging and other sensors.

Cameron Bergen, CEO of Mode40, a Canadian consultancy, works with a range of manufacturing companies in both the United States and Canada. Bergen believes that the Canadian sector is far outpaced by American industrial adoption of new, automated business practices.

“The AI-robotic innovations entering meatpacking draw the principals heavily from other sectors like surgical robotics, automotive manufacturing, and advanced material-handling systems,” he said. “The difference is that those industries have massive economies of scale that drive rapid iteration and standardization. Meat processing doesn’t.” Adoption of automation in beef meatpacking has lagged behind other industries because “the technology hasn’t been configurable, adaptable, or affordable enough for high-mix, variable raw inputs,” according to Bergen.

Cow Crisis

As the beef plant undergoes structural changes, economic trouble has hit the U.S. market. Ground beef is 51% more expensive than it was in February 2020, a spike created by a classic supply and demand dilemma: Just as demand for red meat is going up (and TikTokers are eating their steak off cutting boards), a drought cut the American cattle herd to the smallest supply it’s been in 75 years.

The cattle market is facing a historic supply low, and as a result, meat giant Tyson Foods announced that it would be closing their Lexington, Nebraska, beef slaughterhouse, eliminating 3,200 jobs in a town of 11,000, and eliminating one of two shifts in their Amarillo, Texas, plant. These moves will reduce the nationwide beef processing capacity by 7-9%. In 2025, Tyson Foods expects a $600 million operating loss on beef.

In 2023, Tyson committed to invest $1.3 billion to automate meatpacking processes.

What the Consumer Wants

While price optimization is the primary driver of automated meatpacking, not all consumers are interested in the cheapest version of their favorite cut of meat. As specialty grocers become more popular in high-spend metros — and as protein-loading continues to dominate diet trends — a demand for independent butcher shops may follow suit.

Bradley Darr, a veteran whole-animal butcher at The Meat Hook in Columbia County, New York, came into the trade after decades in the restaurant industry. The art of whole animal butchery, he said, includes an attention to detail that machines will find hard to match. While a mass return to mom-and-pop butcher shops is an unlikely fantasy, the option to shop from local operations does have demand from consumers seeking a higher quality cut.

“There are so many hidden gem steaks that you are never going to see outside of all animal butcher shops. [For instance,] two little steaks sit in the hip joint: they’re called oyster steaks or spider steaks. They’re so small, you’ll never see them in a grocery store.”

Independent butcher shops are not going to be able to offer prices that match the machine-slaughtered meat available in chain grocery stores. And there are many other signs of automation in the food supply chain that have become visible over decades of industry shifts. While white-collar, “knowledge economy” jobs are considered first in conversations about AI disruption and job instability, physical labor — often staffed by immigrants and people of color — is just as susceptible, if not more so, to replacement by machines.