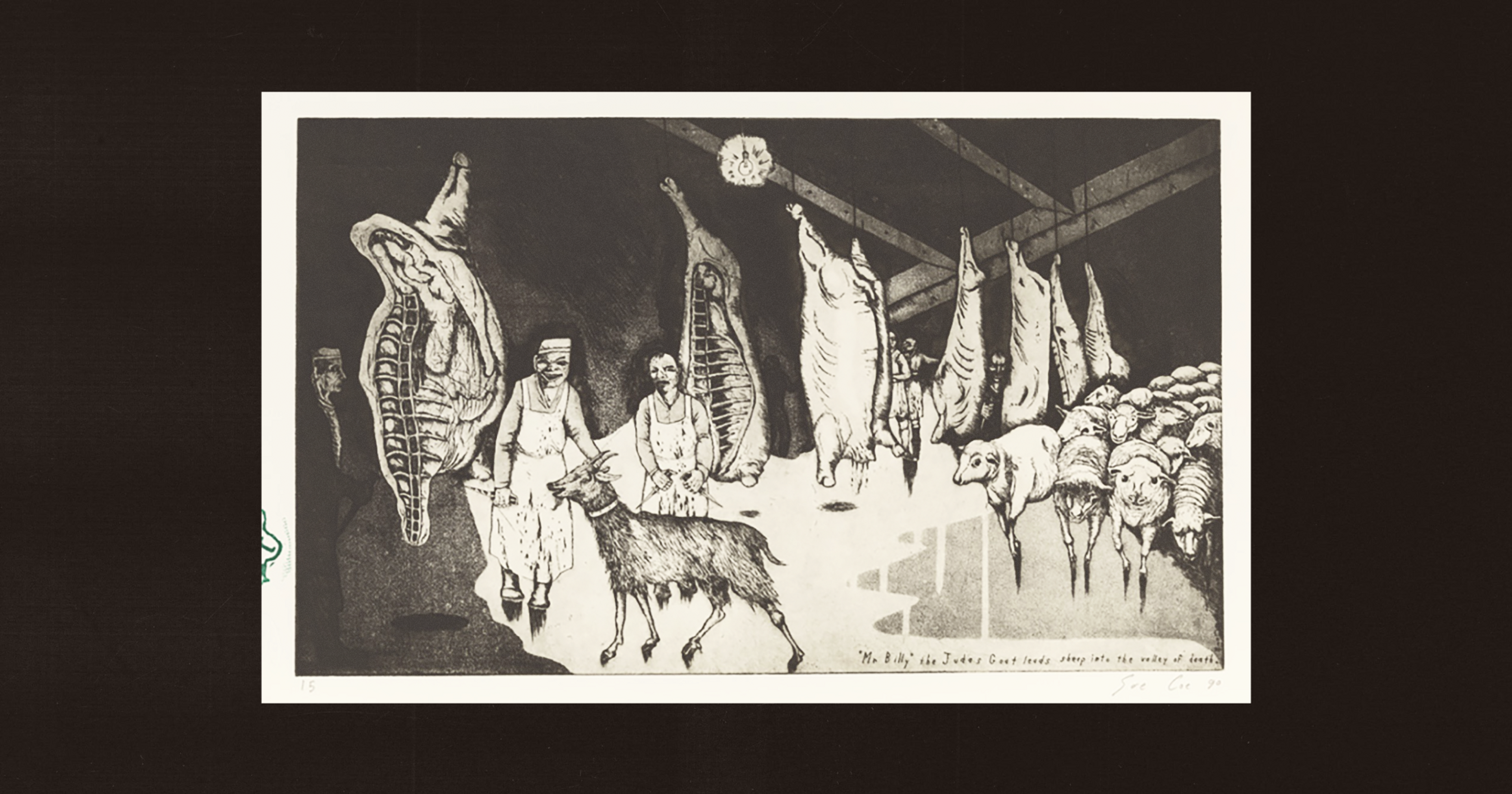

Named for leading their fellow livestock into slaughter, these betrayers aren’t as common as they used to be. But they’re still around.

In the American meat processing plants of yesteryear, sheep destined for dinner plates didn’t follow humans to their final destinations. Instead, they trailed behind aptly named Judas goats, trained to “betray” other livestock by leading them to slaughter.

In a move meant to keep the sheep docile, the plant’s live-in Judas goat would receive training to routinely lead the flocks to their fates like a four-legged pied piper, stepping aside after completing the job — and often earning a reward of a cigarette to munch. The natural instinct of sheep makes them prone to follow a leader, even to their demise.

With a bell around its neck and tobacco in its belly, the goat would carry out its duty, time and time again at the slaughterhouses of the 20th century. The Judas goat’s harsh moniker was given because it leads fellow animals to their deaths, though today’s agriculture experts would be more likely to characterize them as leaders.

Today, its legacy lives on as they and other lead animals continue to herd on smaller scales nationwide.

By 2023, the practice of training goats to lead animals at abattoirs had somewhat fallen out of vogue, due in part to higher consolidation in the meatpacking industry that forced smaller players out. Still, from Texas to Hawai’i, farmers and government officials rely on Judas goats and other lead animals for duties that humans can’t fulfill.

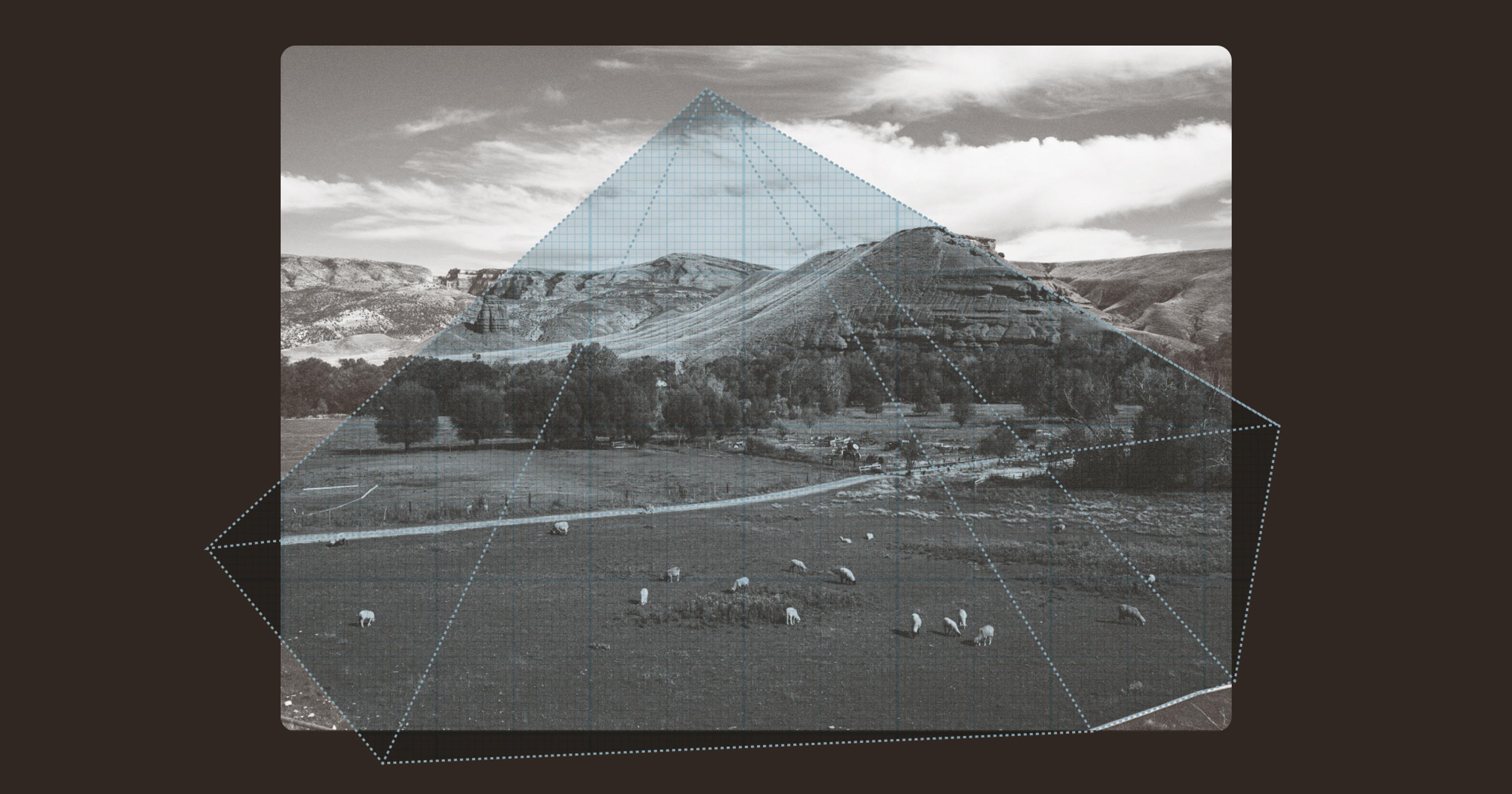

The Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island currently serves as home to three Judas goats — the final agents of an effort first launched in 1981 to protect the local ecosystem, said park spokesperson Jessica Ferracane.

Because goats are considered invasive and destructive mammals on the islands, the government tried to rid them from the park in the 1980s through fencing and other methods of removal. The park staff’s initial success meant only around 250 goats remained, but they lived in small groups across remote areas spanning a total of about 80,000 acres, Ferracane said. They were exceedingly difficult to track.

In order to wipe out those herds, employees turned to Judas goats to lead them to the rogue animals. They fastened radio-tracking collars to kids, which are more likely to find the other goats “because they don’t want to be alone,” Ferracane said. Although the technique isn’t entirely foolproof — for instance, the Judas goats might stay solo or their collars could malfunction — she called it “a cost-effective method” for the job.

Across the Pacific Ocean, officials on the Galápagos Islands also embraced Judas goats at the turn of the 21st century as their solution to exterminating its non-native goat population, which was wreaking havoc on the islands’ habitat. In an effort similar to the Hawaiian initiative, Judas goats led them to the other goats, with the project considered a success by 2006.

They fastened radio-tracking collars to kids, which are more likely to find the other goats “because they don’t want to be alone.”

In addition to tracking other goats, they’re also still used to herd livestock. Dana Stewart of the Martin Cattle Company in Judsonia, Ark., first witnessed Judas goats at work a few years ago at a sheep and goat auction in Texas.

“It was very fascinating to see sale animals follow the lead goat, or Judas goat, into the ring,” she said. “Watching these Judas goats work was like watching a well-orchestrated system of moving parts — livestock and people working together.”

The Judas goats would bring groups of animals into the ring, then lead them into pens or outside of the arena following transactions. “This went on throughout the sale, sometimes with another Judas goat offering relief to the others, like subbing players on a sports team,” she added.

Stewart, 40, counts as the sixth generation to reside on her family’s beef cattle farm. Her great-great grandfather purchased Hereford cattle in 1936, intending to raise registered seedstock and sell bulls to other ranchers. Five years ago, the family also began selling goats to 4-H and National FFA Organization students, with about 60 in their herd right now.

“Having a trained animal to lead the herd is a smart move,” she said. “If there’s not a leader, it takes more manpower to gather the animals and move them to where they need to go.”

Instead of opting for Judas goats, Stewart’s farm uses individual cows to drive each pasture group when it’s time to eat or move. Often, an animal naturally leads the herd — a cow “that, without fail, is always the first to come” when called. “If you can get one or two moving in the right direction, most of the herd will follow,” she said.

For instance, in a natural goat herd, the group relies on a pecking order of dominance that results in a top buck and a top doe, according to Cornell University. The doe’s responsibility is to lead the herd to graze.

Some slaughter plants and feedlots still utilize Judas goats, although “good facilities should negate the need for them.”

In a domestic herd, if a human takes on the role of feeding the goats, “the herd may attempt to follow you wherever you go,” Cornell reports. “This becomes a problem when you try to send the herd out to pasture and they keep trying to follow you home.”

And among sheep flocks, commercial operations use Judas sheep from the farm to transportation to marketing to processing, said the American Sheep Industry Association’s Amy Hendrickson. She called the term Judas sheep “simply another name for a ‘lead’ sheep,” noting that sheep will easily follow a leader.

“These sheep live for years on an operation, providing wool but obviously no lamb production,” Hendrickson said. She called the use of lead sheep “simply another management tool, similar to herding or protection dogs.”

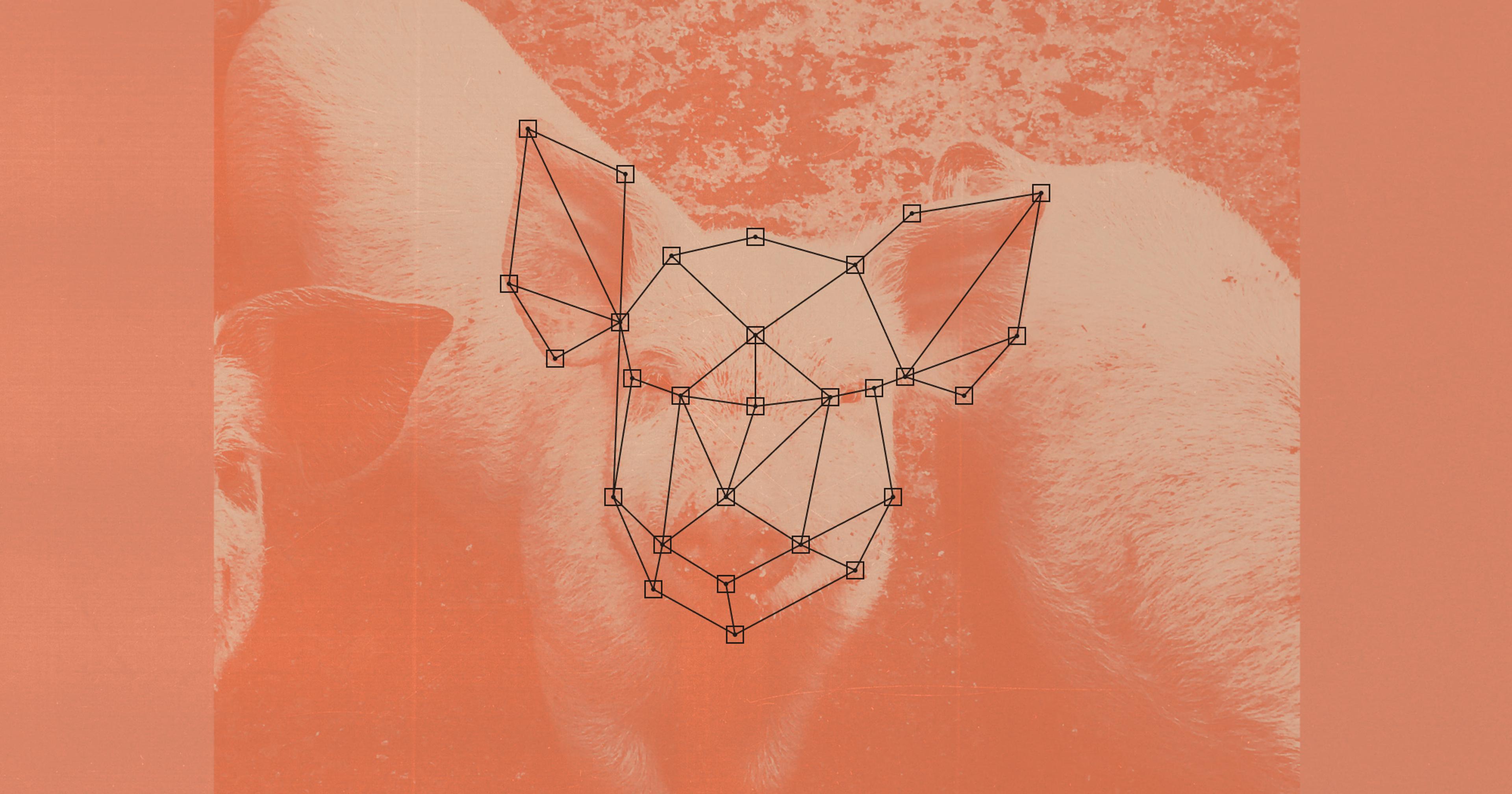

Casey Kammerle, spokesperson for the North American Meat Institute, described sheep as gregarious, making them “more at ease following a lead animal, which limits the need for human handlers, which could cause additional stress.”

Many farms depend on leader animals — “not necessarily goats” — to guide the others, said Susan Schoenian, sheep and goat specialist emeritus at the University of Maryland Extension.

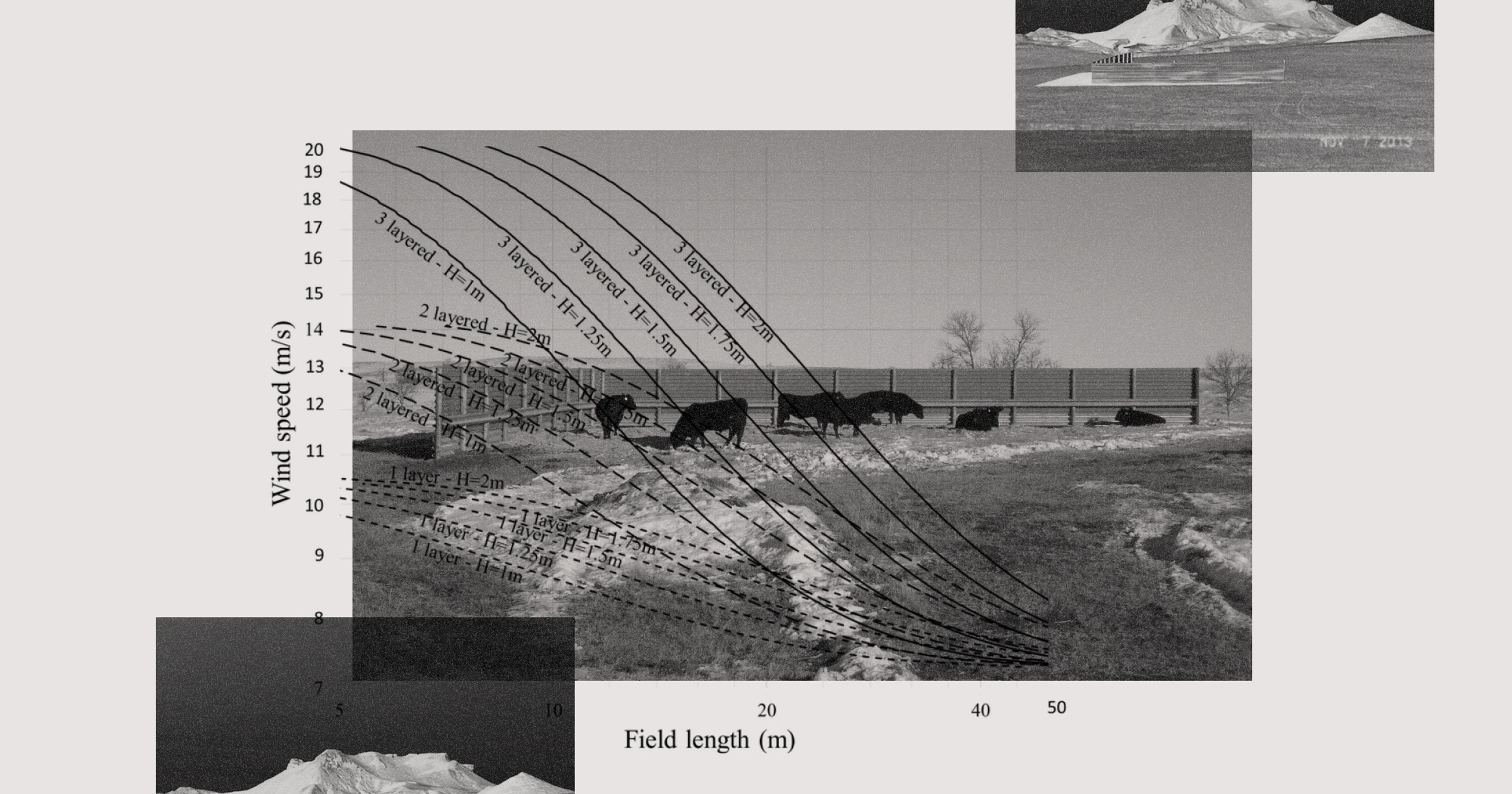

Some slaughter plants and feedlots still utilize Judas goats, although “good facilities should negate the need for them,” she said. This can be achieved through intentional design. “With pens and corrals, the animals can be moved naturally from one point to another, following the one ahead of them,” Schoenian said. “There are specific ways to design facilities to move animals through slaughterhouses naturally.”

Although the role of the Judas goat has evolved over time, and expanded to include other lead animals, some can recall its original purpose. Even without an agriculture background, Allan Musterer, 80, ties a distinctive moment in his childhood to Judas goats. In the 1940s, his father brought him and his brother to a Hoboken, N.J., slaughterhouse run by a fellow church congregant.

After taking them to a corral of lambs, his dad fed several cigarettes to the flock’s lone Judas goat — a bell hanging around its neck, Musterer said. A noisy signal at the plant spurred the goat into action, gathering the livestock and marching them onward.

“They just kept following and following, lamb after lamb, until all the lambs were in that chute,” Musterer said. “The goat came out, the door closed, and the lambs went off to slaughter.”