Animal chiropractors can complement traditional veterinary care through noninvasive, drug-free adjustments focused on spinal alignment and joint movement.

In a corral that skirts a weathered red barn, Emily Black approaches a chestnut brown horse, placing her hands against its shoulder, careful not to press too hard as she works with the animal to correct a joint that’s lost its full range of motion. It’s part of her typical day — and the horse is one of her regular patients — as an animal chiropractor who serves clients along US-131, from Kalamazoo to Traverse City, Michigan.

Black is part of a developing field of specialists — chiropractors certified to work on animals large and small. “Instead of treating just a six-inch square on a human, I’m able to treat both humans and all sorts of animals,” said Black, whose client list is about 75% animals and includes horses, cattle, alpacas, goats, and pigs. She also provides chiropractic services to humans on some of the farms she visits. “Vets recommend chiropractic adjustments for several reasons, such as pain relief, performance enhancement and overall wellness.”

Animal Chiropractors 101

Animal chiropractors have been around informally since the early 1900s. However, it wasn’t until the late 1980s that Michigan veterinarian Sharon Willoughby-Blake became interested in chiropractic care after seeing its effect on a canine patient, and a small group of colleagues founded the first school and established certification standards. In 1989, the American Veterinary Chiropractic Association (AVCA) opened as a central place for those interested in pursuing careers as animal chiropractors. Later, Willoughby-Blake also opened the Options for Animals College of Animal Chiropractic headquartered in Kansas, which provides the coursework needed to become a licensed animal chiropractor per the AVCA and International Veterinary Chiropractic Association (IVCA).

To date, there are 803 animal chiropractors licensed by AVCA and 714 by IVCA. A veterinarian or human chiropractic degree is required before becoming an animal chiropractor.

“It’s about 250 hours of education along with hands-on training with animals,” said Jess Stief, an animal chiropractor based in Illinois. Stief works with a variety of farm animals along with smaller animals like dogs and cats. “You sit for a board exam with either the AVCA or IVCA. Once you get your license, there’s continuing education and you re-license every couple of years — just to stay current.”

But What Does an Animal Chiropractor Do?

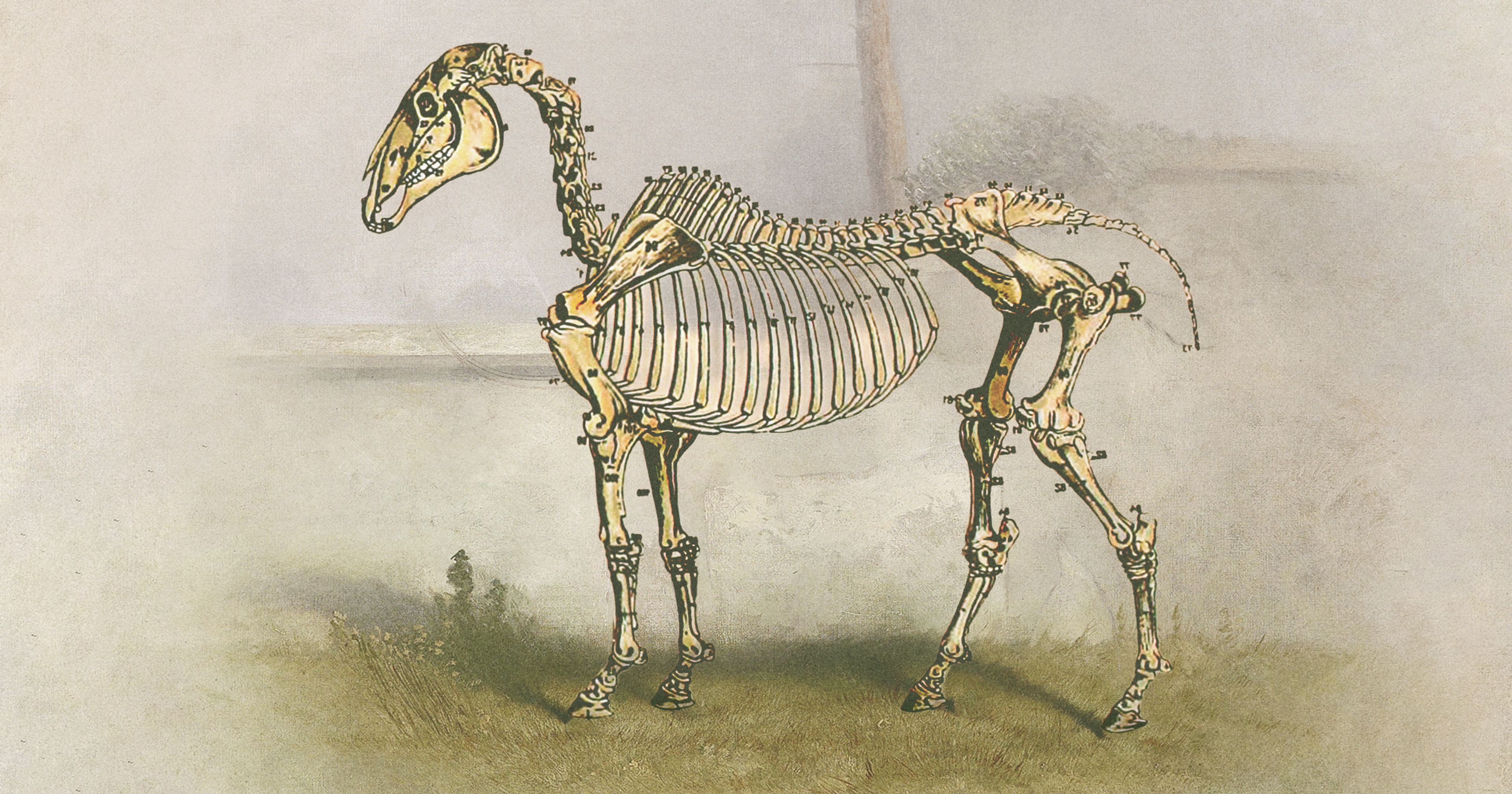

Just like humans, animals can develop issues with joint mobility, spine alignment, arthritis, muscle spasms, and more. While traditional veterinary medicine often turns to pharmaceutical solutions, an animal chiropractor focuses on correcting alignment and function with physical intervention.

“Imagine large working draft-type horses getting sore and experiencing dysfunction in their back end, dairy cows getting sore in their hips and stifles from their udders, show goats presenting with sore necks from training, and agility dogs with sore shoulders,” said Black.

Common ailments where a farmer or rancher would contact an animal chiropractor or request a referral from their vet include problems with an animal’s gait, posture, chronic pain, mobility issues, and behavior such as extreme stress or anxiety.

But it’s not like animal chiropractors are putting the cow or horse up on a drop table like a human chiropractor does. Stief, for example, uses a step stool or ladder, depending on the size of the animal she’s treating, in order to get to the right angle to adjust their spines, pelvis, or hips. Black often moves with each animal, say, applying pressure to a horse’s shoulders while it is walking.

Livestock vs Humans

Animal chiropractic adjustments are similar to human chiropractic adjustments. Once the chiropractor locates the problem area — usually one with decreased or restricted motion — they apply a “high-force, low-amplitude thrust” specific to that joint to regain normal movement. For Black and Stief, this equates to gentle pressure with ideally little to no pain during the adjustment.

Without any “conscious, verbal communication,” according to Stief, they must rely upon non-verbal cues, especially when it comes to farm animals. “Most of them are going to be flight animals, right? They’re prey animals so my work with a dog versus cattle in that regard, I have to take into account how they’re wired a little bit differently.”

And, of course, it depends on the type of animal. For example, a horse will be used to human contact through regular grooming and riding, while a dairy animal that’s had little human touch tends to be more skittish, providing a much smaller window in which it can receive care.

“Once in a while, if something is really sore, I’ll get a little ear flick here and there, or somebody will kind of cock a leg or bite a little, but really, there’s not a lot of that aggression at all,” said Black.

But Is There Proof?

Chiropractic care, in general, is often met with skepticism as some practices or therapies lack scientific-based evidence proving that they’re beneficial. Further, within the animal chiropractic field, some veterinarians argue that there’s no evidence that these sorts of adjustments actually improve animal health. And, if animals can’t talk, how do animal chiropractors know the adjustments are working? Observance of better mobility and motion, the appearance of reduced pain and discomfort, and improved gait and posture, according to Black.

Rachel Rice, co-owner of True North Equine LLC at Cold Spring Farm in Maple City, Michigan, said she can attest to the value of an animal chiropractor’s abilities to keep animals like the horses she trains healthy and happy.

“Horses are always just messing around,” said Rice. “They lay down and roll and throw their neck out of place. It doesn’t take much for them to mess themselves up.” Especially since many of the horses she works with also barrel race, Rice has Black out monthly to work on 12 to 15 horses — she said the results speak for themselves.

“We had this mare with some underdeveloped muscle,” said Rice. “The horse’s withers, which are like extensions of their vertebrae right above their shoulders, had sunk down below her shoulder.” Rice credits the horse’s recovery to regular chiropractic adjustment, specific exercises and the use of MagnaWave — an unverified type of therapy that claims to use electromagnetic pulses to stimulate cellular activity, improve circulation, and promote healing. “The mare now has correct position and her back’s lifted up, allowing her to compete at a much higher level than she was previously.”

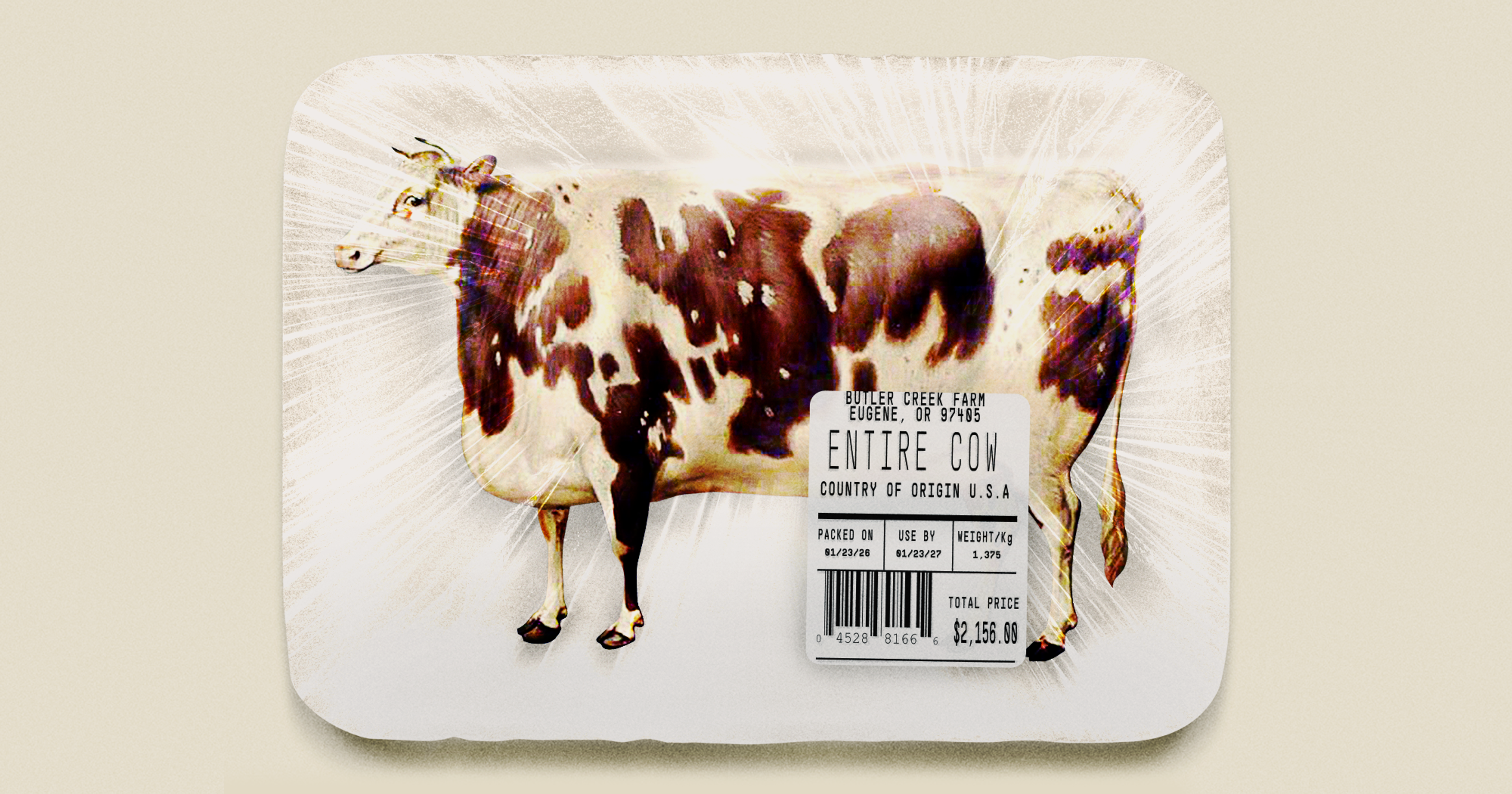

Instead of thinking of it as an either/or situation, the work of animal chiropractors can complement traditional veterinary care.

“The overall medical field and people’s interest in alternatives that are noninvasive, that don’t require drugs — these types of approaches, I think, are just growing in popularity and understanding around a healthy animal,” said Stief.

“This isn’t a replacement for traditional veterinary medicine,” said Stief. “But I will say I think the veterinary field — just like human medicine has — is getting more open-minded and holistic in its approach. I’ve never had a veterinarian respond poorly to the work I do.

“An animal that feels better in their body is going to have lower cortisol levels, it’s going to feel better, it’s going to digest its food better and so what you’ll notice is an animal — whether it’s a farm animal or a horse — is that if it feels better, you’re going to see overall improvement in the quality of life, whether you’re measuring performance or digestion, you’re going to see changes as that body falls back into homeostasis and balance.”