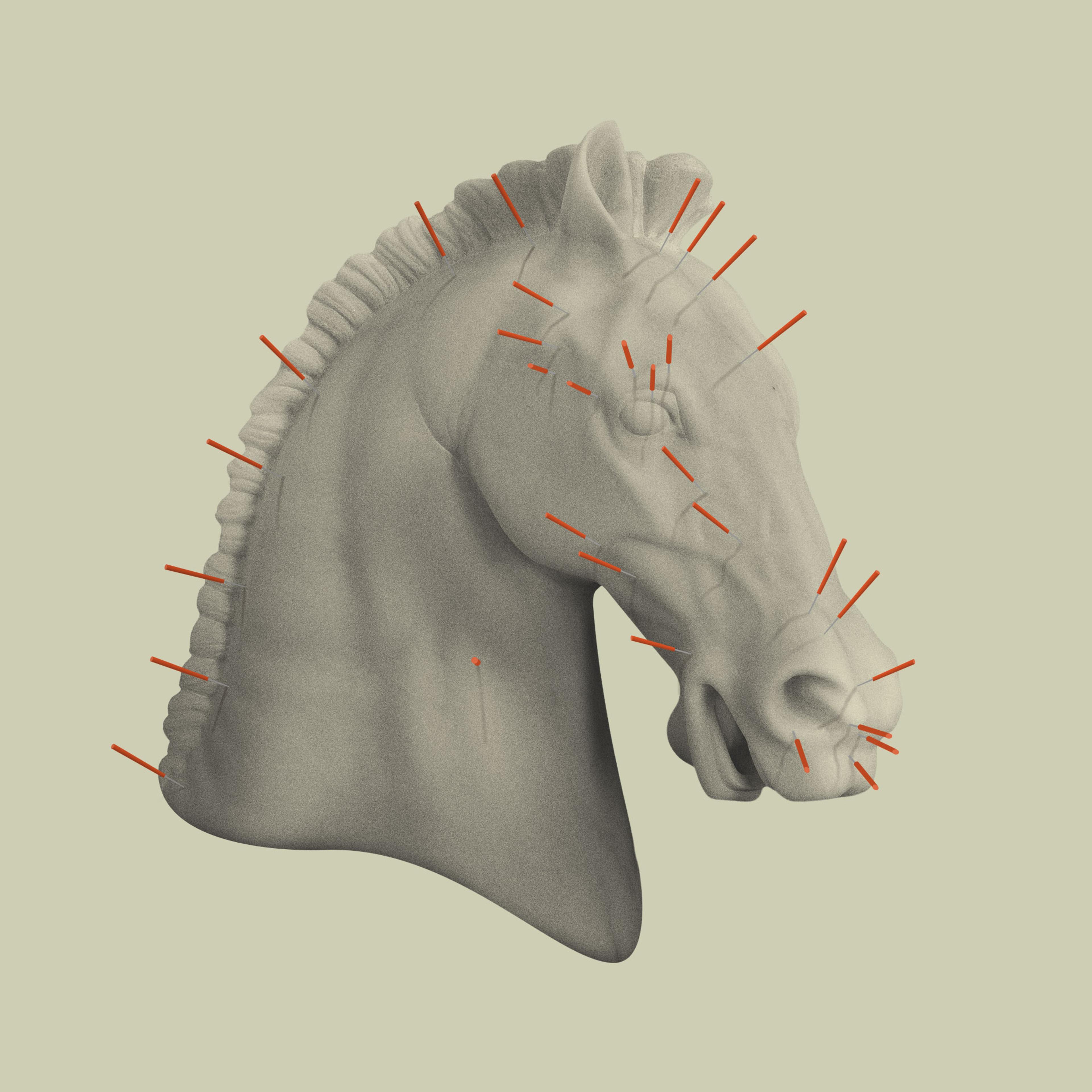

The professionals tasked with keeping our livestock healthy are increasingly looking to less conventional techniques like applied kinesiology, acupuncture, and chiropractic care.

Livestock come in all shapes and sizes, fulfilling an array of assigned roles in the agriculture industry. Whether they’re a bucking bronco or rodeo bull in the performance sector, a dairy cow in the milking parlor, or a young calf racing its mates across a grassy pasture, they all regularly face injury risks, a reality underscoring the need for mindful stewardship in managing their well-being.

Enter the traditional, Western medicine-based large animal veterinarian.

These professionals fill this caretaker role much like our own doctors: diagnosing, treating, and preventing diseases, while also providing preventative care for whole-body wellness. The vet’s roles range from administering vaccinations to performing surgeries, depending on the specific needs of the animal at hand.

Yet some practitioners have found that traditional Western techniques are not enough to meet the veterinarian’s version of the Hippocratic Oath, and are turning to complementary or integrative treatment therapy tools, including applied kinesiology, acupuncture, and chiropractic care, to fill in the gaps.

These DVMs claim that integrating non-Western care methods with traditional practices can offer a more comprehensive and holistic approach to managing health issues. Anchoring these philosophies is the belief that all animals are unique and their care requires a customized methodology. Integrative care practices can help provide a more complete picture of an animal’s well-being, addressing pain, mobility, musculoskeletal problems, and even neurological and digestive conditions with potentially fewer side effects than conventional medications or surgeries.

Applied Kinesiology Turns on the Power

Dr. Keith Wagner, a seasoned Missouri-based DVM practitioner, works with horses of all ages, levels, and dispositions, ranging from Olympic athletes to acreage pets. He began his practice as a traditional Western medicine-based veterinarian, but over the last 15 years, he’s transitioned roughly 80% of his methods to applied kinesiology, acupuncture, and chiropractic treatments.

“I just had to make a change,” Wagner explained. “It was in my nature to continually ask why things happened and why something worked or didn’t work. Because of all these questions running around my mind over the years, I began adding and tweaking small things, slowly changing the way I was approaching health issues and how I treated them.”

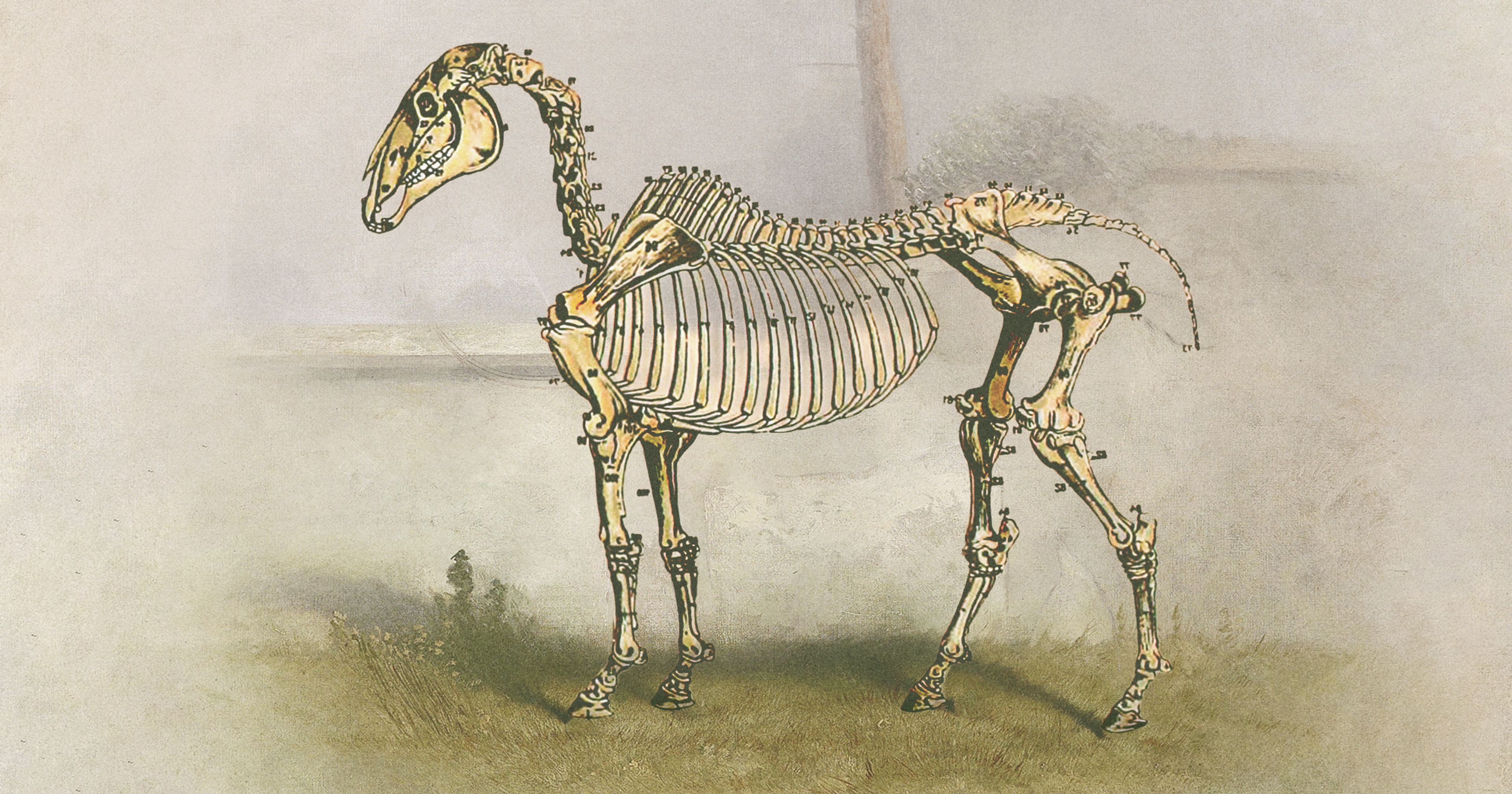

His diagnosis method of choice is applied kinesiology (AK), also known as muscle testing, a diagnostic process to assess and treat functional illnesses and neurological imbalances. AK is a supplementary approach to standard medical practices, evaluating muscle responses and aiming to identify underlying nervous system dysfunctions that may contribute to health issues.

“I examine and assess the electrical function of the individual by touch to test muscle strength,” said Wagner.

Using applied kinesiology, Wagner checks approximately 25 central pattern generators (CPGs), essentially making up the hard wiring of the nervous system. Each CPG has an indicator muscle that becomes weak when CPG dysfunction occurs. Injury or pathological changes in the body create this dysfunction.

“Because of all these questions running around my mind, I began adding and tweaking small things, slowly changing the way I was approaching health issues.”

“When the muscle weakens across a joint, stability is lost, causing laxity or play during movement, followed by inflammation,” Wagner said. “Once I identify the problem CPG, I can essentially turn it back on to help restore the joint’s stability.”

Typically, these inflammations and weaknesses are treated with injections into the affected joint.

While applied kinesiology is Wagner’s primary diagnostic tool, he typically follows up with chiropractic procedures or acupuncture.

“To address the ongoing cycle from youthful wellness to later disease in horses and humans, early treatments such as acupuncture, applied kinesiology, and chiropractic care have preventative benefits,” he said. “These methods focus on maintaining balance within the body and preventing minor issues before they become major health concerns. In contrast, traditional Western medicine becomes more beneficial during later stages, providing effective treatment at end-of-life.”

Wagner believes combining these approaches delivers more comprehensive life cycle health and disease care.

“We correct the mechanical functions, which in turn helps us not to go down the aging and disease path so quickly,” he said. “In a perfect world, using complementary care earlier in life and Western-based medicine later should be the goal. We can’t stop disease and death, but we can slow or restrict them.”

Breaking Out the Modalities

Dr. Quinley Koch, owner of Elite Equine and Veterinary Services in Wichita, Kansas, offers acupuncture, chiropractic, traditional Chinese medicine, and physical therapy for horses, cattle, and rodeo bucking bulls. Traditionally trained in Western veterinary medicine, Koch eventually branched into “integrative” work, a term she’s passionate about; she considers the often-referenced “alternative’” a misused word.

“First, these types of modalities are not ‘alternative’ to anything,” Koch said. “With many procedures, for example, neutering, there’s no alternative. Alternative is not an accurate term for what I do. Integrative is much better as it allows different processes and philosophies to work together.”

She commonly works with other veterinarians who provide vaccinations, joint injections, colic treatments, and other mainstream protocols. Koch said most members of the animal health and performance sector, including owners and veterinarians, use at least some form of integrative medicine as they’ve witnessed its positive results firsthand.

“There’s ample room for both mainstream and integrative practitioners. It’s an amazing, symbiotic relationship, achieving superior results.”

“There’s ample room for both mainstream and integrative practitioners,” she said. “It’s an amazing, symbiotic relationship, achieving superior results. Group efforts are far better than singular endeavors.”

Koch focuses on muscles, the nervous system, bones, and tendons, but her processes include the entire body. “The beautiful thing about acupuncture and physical therapy is it’s a whole-body approach,” she said. “If I help balance the body better than the body balances itself, it’s successful without using medications.”

Like Wagner, Koch also believes the veterinary community is changing, becoming more accepting of integrative methods. She thinks the shift started with human medicine, then trickled down.

“A huge push has occurred for integrative strategies on the human side as more and more people have tired of doctors prescribing medications without finding root causes,” she said. “With chiropractic treatment, acupuncture, and Chinese medicine, we’re able to find and treat the root cause along with the symptoms. Human medical shortcomings have created this massive interest, which has pushed its way into the veterinary field as owners want to treat their animals the same way they want to be treated.”

Claiming the Well-Traveled Road

Typically a veterinarian is called to assess, diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate using traditional, mainstream medical practices.

“When I’m faced with a new large animal patient, I start with a strong Western approach including a visual assessment, a thorough physical exam to make a diagnosis, radiographs, and lameness locators for travel issues, discussions of nutritional health, and sometimes a neurological exam,” said Kelsey Walker, assistant clinical professor at the Oklahoma State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “Treatments often consist of antibiotics for infectious diseases, pain medications, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), joint injections, plus surgery to insert pins and plates.”

Walker treats all types of livestock from rodeo bucking stock to sheep, goats, and pigs. “Our clinical management depends on where the underlying source of the problem is found,” she said. “These large animals are often aggressive, of course, but we complete our Western-based protocols, keep them in the hospital, and apply a lot of positive reinforcement through their rehabilitation process. It’s amazing when fire-breathing dragons [Ed. Note: not actual dragons] limp into the clinic, and a few weeks later, they’re begging for scratches as they proudly walk back into their normal lives.”

Walker believes mainstream medical research and trials create the underlying foundation of performance animal care, reinforcing diagnosis and treatment protocols, and installing qualified and certified caregivers.

“The biggest problem is that we’re years behind human medicine, but we’re expected to provide the gold standard with data we don’t have. Continuing research is so vital to keep progressing.”

She notes Chinese medicines and herbs can help but is concerned about unregulated products and withdrawal times. She’s also seen modalities being misused and causing injuries by those without the correct training. If practitioners are certified with appropriate training, they can hold a positive place. She even utilizes acupuncture in her own treatment regimen when she deems it necessary.

“We’re all striving for the same results, and every integrative practitioner I know is willing to work together with more mainstream Western medicine practitioners.”

“For emergency matters like broken legs and acute illnesses, in my opinion, it’s obvious traditional Western practices fit best,” said Walker. However, “Due to how the body responds to long-term pain management, for more chronic issues, other modalities might be more effective,” she admits.

Walker credits a new generation of veterinarians and the open-mindedness of the general population with a shift to more out-of-the-box diagnosis and treatment methods.

“We’re all striving for the same results, and every integrative practitioner I know is willing to work together with more mainstream Western medicine practitioners,” Koch said. “By using a well-balanced strategy mix, we can provide the best possible, whole-body care.”

All three DVMs admit that both human and animal health have a long way to go. “Roadblocks to performance animal care include the same issues as on the human side,” Walker said. “Much of it comes down to education and explaining what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. Clients are asking for these modalities. They should be able to coexist successfully with Western veterinary medicine. I think it’s the way of the future.”