Manure management on cattle farms is key to stemming antibiotic resistance, new research finds.

In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration banned the usage of antibiotics as growth enhancement for livestock. This was enacted to stem the growing resistance of bacteria to antibiotics, which had manifested into a significant global public health threat. We’ve seen the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and antibiotic-resistant genes (ARGs), which reduce the effectiveness of critical medicines on humans.

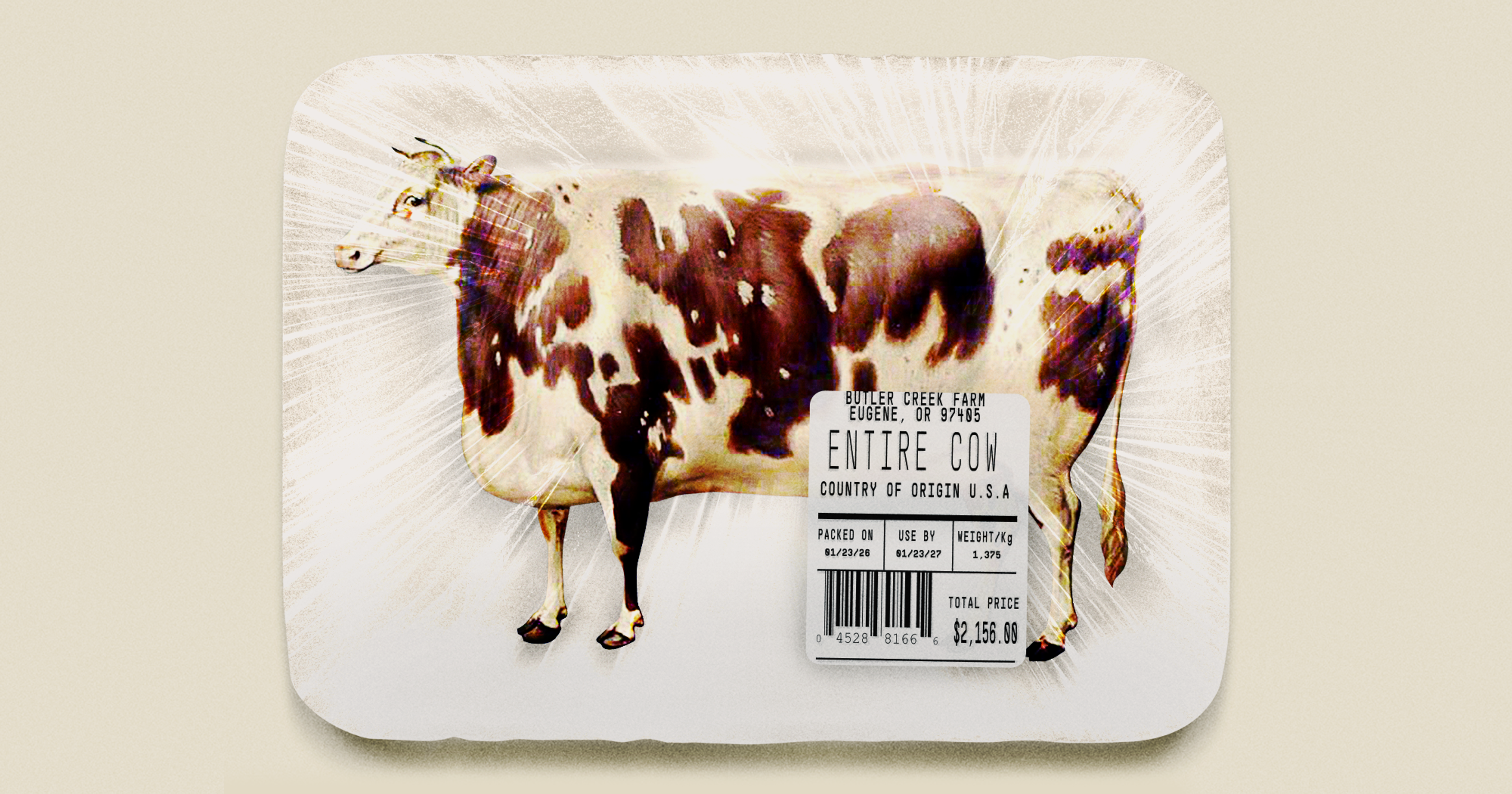

Now, a team of researchers has found significant evidence of global health risks in livestock waste or manure, posing as an important vector for ARGs. When animals are given antibiotics, resistant bacteria and their resistance genes can build up in their guts, which is then excreted into manure.

“Livestock manure carries antibiotic resistance genes that can defeat every major class of antibiotics used in human medicine — including those considered ‘last resort,’” said Xun Qian, professor at the department of environmental science at China-based Northwest A&F University, one of the authors of the study. This makes manure one of the most concerning reservoirs of resistant bacteria in the environment, he added.

ARGs are zoonotic pathogens that can be transmitted to humans through food. What was most worrying for the authors was that the genes were often located on mobile DNA elements, which meant they could move from harmless bacteria in manure to dangerous pathogens, potentially creating “superbugs that are hard to treat.” The authors analyzed over 4,000 livestock metagenomes — a study of genetic material from organisms — in 26 countries, and devised a comprehensive catalog of livestock ARGs. The United States and Brazil, leading global beef producers, showed the highest resistome abundance in cattle manure when compared to other countries.

How manure is managed makes a huge difference, according to Siddhartha Thakur, veterinarian and executive director of Global One Health Academy, a research organization at North Carolina State University. One of the ways bacteria are commonly transmitted is through food. When arable land is treated with manure that is not properly composted, crops grown underground and even above-ground plants like tomatoes become susceptible. For example, salmonella can grow inside a tomato, which means washing it externally is not going to help when the tomato is consumed raw, said Thakur, who has over two decades of experience in the study of antibiotic-resistant foodborne pathogens.

“Livestock manure carries antibiotic resistance genes that can defeat every major class of antibiotics used in human medicine — including those considered ‘last resort.’”

Leafy greens have been associated with a fair share of foodborne illnesses. A 2023 listeria outbreak was linked to lettuce, while kale and spinach emerged as culprits behind a 2021 E. coli outbreak. A recent paper put things in perspective when the authors attributed 9.18% of foodborne illnesses to pathogens associated with leafy greens, which meant these greens accounted for almost 2.3 million illnesses — the costs of which can rise as high as $5.2 billion annually.

These outbreaks often stem from the usage of water contaminated with faecal matter of cattle to irrigate crops, illustrating the magnitude of the threat outlined by the study’s authors.

Further, the global disease burden for antimicrobial resistance remains high. In 2021, a study published in The Lancet estimated that 4.71 million deaths were associated with anti-microbial resistance between 1990 and 2021. This death toll is estimated to reach almost 10 million by 2050. Given this, the Chinese scientists intend for their new research to help governments target surveillance, policy, and interventions where they are needed the most.

One of the major challenges with ARG-related deaths is the issue of underreporting, Thakur pointed out. “Surveillance programs figure out how many people died. [In] many of the low to low-medium-income countries, the surveillance programs are not robust enough to catch the people who have died,” he added, stating that we might already be inching closer to the 10 million threshold.

Xun also mentioned that applying untreated manure to fertilize farm fields can increase transmission risks. One of the best ways to reduce this risk, he noted, is to reserve antibiotic usage for treating actual infections.

4.71 million deaths were associated with anti-microbial resistance between 1990 and 2021. This death toll is estimated to reach almost 10 million by 2050.

This holds true for Bill Niman of Niman Ranch, who made that choice in 1975. He told Offrange that they use antibiotics only when necessary — when animals get sick. To avoid frequent sickness, the ranch keeps a lower number of animals, which affords the pigs and cattle more space. And while he believes in treating sick animals with antibiotics, he found no reason to feed the cattle the drugs otherwise. “[Antibiotic usage] only works as a compelling business model,” the 80-year-old said — the cons to growth enhancement far outweigh the pros.

Meanwhile the regulations governing antibiotic usage in livestock have been getting tighter. “The Food and Drug Authority guidelines (209 and 213) prevented the over-the-counter sale of medicated feeds and prevented growth promotion use of medically important drugs,” said Thakur. He also noted that over the last 10 years, there has been a 37% decrease in drugs that are medically important for human use in the food animal industry.

Notably, we observed a decline in ARG abundance in U.S. swine manure between 2016 and 2018, which may be linked to the implementation of the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD) in 2017,” Xun said. “This provides encouraging evidence that well-designed regulations can effectively reduce resistance pressure in livestock systems.“