In Montana, free carcass removal programs help ranchers mitigate conflicts with grizzlies, wolves, and mountain lions — and make compost to boot.

When a rancher’s cow dies in southwest Montana’s Madison Valley, Linda Owens is usually the one they call.

A rancher herself, Owens has lived and worked in the valley the majority of her life, raising cattle on her family’s farm outside of the small town of McAllister. In 2017, she joined Madison Valley Ranchlands Group, a local rancher-led nonprofit, as a project director.

The project she leads? It’s a carcass pickup and composting program that removes dead livestock from ranches in order to mitigate attacks from grizzlies, wolves, and mountain lions.

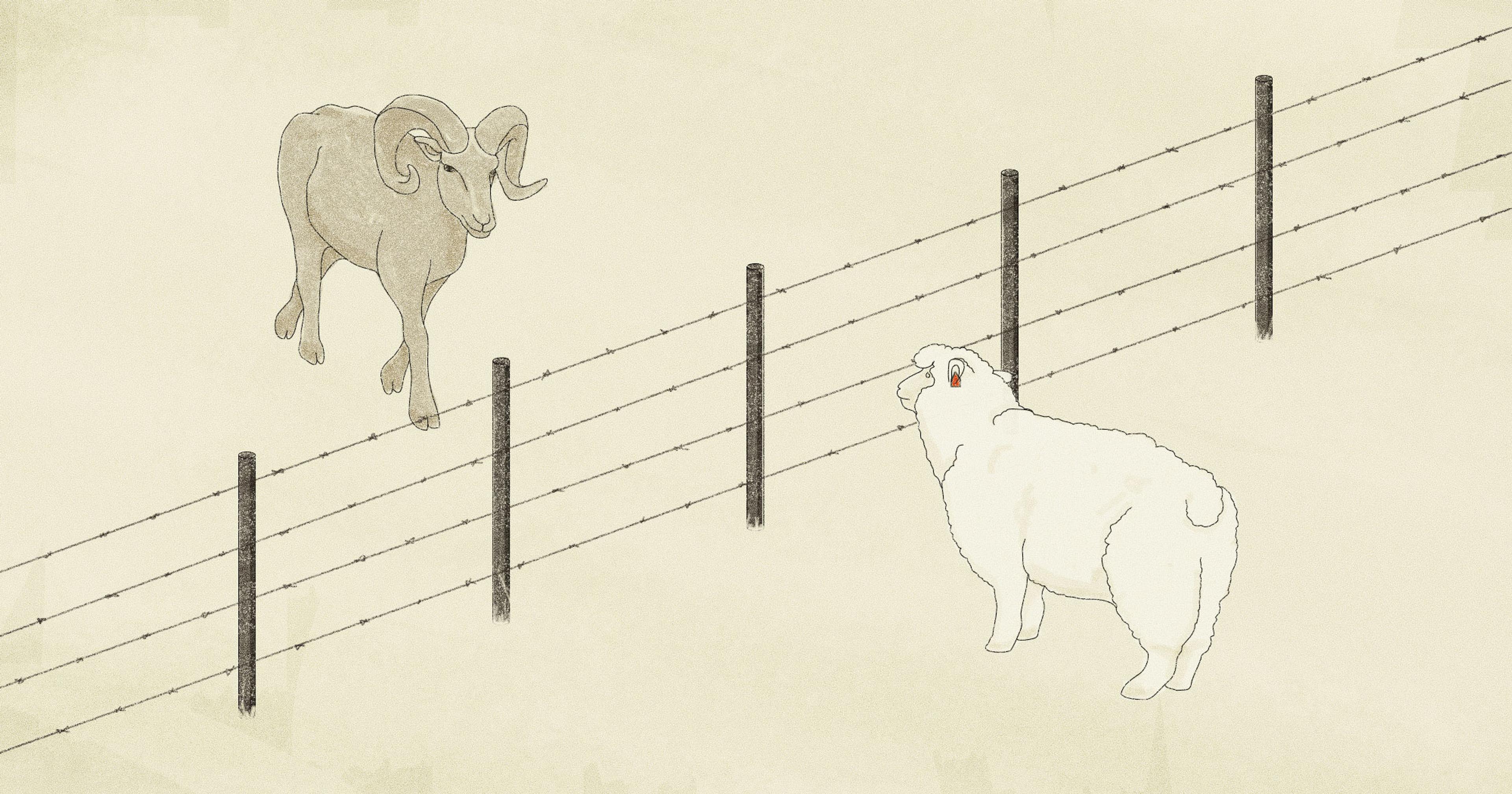

Before the program, ranchers would dispose of any dead animals (an inevitability of ranching) in boneyards, where they would slowly decompose. But these boneyards are smelly and attract vultures, scavenging critters, and large carnivores, too.

This issue has grown in recent years as grizzlies and wolves repopulated Western Montana due to protection through the Endangered Species Act and wolf reintroduction to Yellowstone National Park. Over the past three decades, their numbers have slowly but surely ticked up, requiring some ranchers to implement new management strategies for their operations. That’s where Owens’ program comes into play.

“The carcass pickup is a proactive tool,” Owens said. “What we’re trying to do is not draw [grizzlies and wolves] in and make them feast on something that, even if it’s just scavenging, it’ll get them in trouble.” If the predators start hanging around boneyards and attacking livestock, it could mean their death if a rancher has reason to think they’re a threat. In Montana, it’s legal to shoot a bear if it is attacking or threatening livestock.

That’s the trouble Owens wants to keep grizzlies and wolves out of.

When she gets a call for a pickup, Owens usually shows up same-day to the ranch with a trailer and a winch to haul the carcass out. The cause of death varies, but this year she’s picked up several cows who were struck by lightning.

After loading the carcass into the trailer, which is lined with a biodegradable spill mat to catch any seeping carcass fluids, Owens transports them to a two-acre composting facility surrounded by electric fencing to keep scavengers out. The carcasses (and spill mat!) are covered with soil, manure and straw, sprayed with water, and left to decompose for several months. Unlike the boneyards, there’s hardly any smell, which Owens said helps keep the neighbors happy.

The service is free to ranchers, paid for by private grants from places like the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and Vital Ground Foundation. Owens takes donations, but her perspective is that the service should not come at a cost to ranchers. “I am a firm believer that my ranchers should not be paying for this,” she said. “We are not the ones that asked for the wolves and the grizzly bears.”

Some History

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, wolves and grizzlies were extirpated from much of the West with the introduction of cattle and loss of native prey animals like bison and elk.

Ranchers became accustomed to ranching without these large carnivores on the landscape, so their return has been a difficult transition for some. Wolves have been a particularly contentious topic for Montana and other states like Colorado, where they were reintroduced through a ballot measure in 2023.

Matt Barnes, a wildlife scientist who works with organizations like Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative to help ranchers implement predator management, credits the ongoing debate to the legacy of cowboy culture in the American West.

“I am a firm believer that my ranchers should not be paying for this. We are not the ones that asked for the wolves and the grizzly bears.”

“If you’re the descendant, either literally or figuratively, of the pioneers, the fact that we are now restoring the very species your ancestors worked so hard to get rid of, probably feels like a repudiation of your cultural history,” Barnes said.

The settlement of the West, Barnes said, is often framed as a heroic epic of scrappy young cowboys making a life for themselves on the range and removing predators in the process. But that narrative leaves out the wholesale removal of native wildlife and widespread ecological destruction.

As wolves and grizzlies repopulate their historic habitat, efforts to mitigate conflict with livestock make up the latest chapter in the long story of ranching in the West. While carcass removal won’t ever be a silver bullet to end livestock depredation — experts say there will likely always be some amount of it when ranching in carnivore country — it’s one of the most effective strategies ranchers can employ to protect their livestock.

The Challenges

But getting these carcass removal programs off the ground is not always easy.

In the Madison Valley, it took several years to get approval from county health officials to build their composting facility. Even after they got the green light, finding a location for it proved to be tricky. In the end, they built the facility on private land offered to them by Matt Moen, owner of Bar MZ Ranch. In 2018, they finally started picking up and composting carcasses.

“Departments of health or environmental quality can have some pretty strict laws that make it really challenging to set up these carcass composting sites,” said Matt Collins, the Working Wild Challenge manager at the non-profit Western Landowners Alliance. “Just years and years of red tape and different permitting to get them going.”

Seven years into the program, Owens of the Madison Valley Ranchlands Group said county officials have finally come around to the idea of the composting facility. She’s helped assuage some of their concerns over disease by getting the compost tested twice per year for pathogens like E. coli, salmonella, and brucellosis. Since they started operating in 2018, they have not yet removed the compost to be used anywhere outside the facility.

In the Blackfoot Valley, about 175 miles north of the Madison Valley, the non-profit Blackfoot Challenge has led a similar program since 2003 with great success: About 90% of the valley’s ranchers participate. Their pickup program is also free to use, but runs in partnership with the Montana Department of Transportation and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. That means their composting facility also takes roadkill.

“The fact that we are now restoring the very species your ancestors worked so hard to get rid of, probably feels like a repudiation of your cultural history.”

But with the rise of chronic wasting disease — a fatal neurological disease affecting deer, elk, and moose — some worry the compost the facility produces could spread the proteins that carry the disease. The state has stopped using their wildlife compost to grow roadside vegetation because of this concern, according to the Blackfoot Challenge.

“In one sense, integrating the wildlife and livestock compost can be helpful because these communities have a lot of roadkill,” Collins said. Removing roadside carcasses also protects scavengers like golden eagles and vultures from getting hit by cars as they feast. But limiting the compost pile solely to livestock has alleviated chronic wasting disease concerns. That’s the system Owens has going, and so far it’s working well.

During her first year in operation, Owens wrote out objectives for the program. She hoped for long-term project viability through partnerships with a diverse group of agencies and people, and a healthier and safer landscape for both animals and people.

When asked if she thinks she’s met these objectives yet, Owens was hesitant to say absolutely yes or no. To her, it’s an ongoing process, but a gratifying one. Even if just one cow or one wolf is saved because of the program, she said that makes her work worth it.

“It takes a lot of time, but I feel I’m actually providing something that [the valley] can see a benefit from,” Owens said.