In a farming community that has accepted residential solar but isn’t sure about large commercial facilities, the Thanksgiving meal is coming directly from the solar industry.

Evan Carpenter’s fifth year growing turkeys looks a little different from all the others. Roaming three acres enclosed by electric fence netting and grazing down vegetation, the turkeys are now contracted employees of a solar company in Central New York — and they are likely the only “employees,” of sorts, in the business.

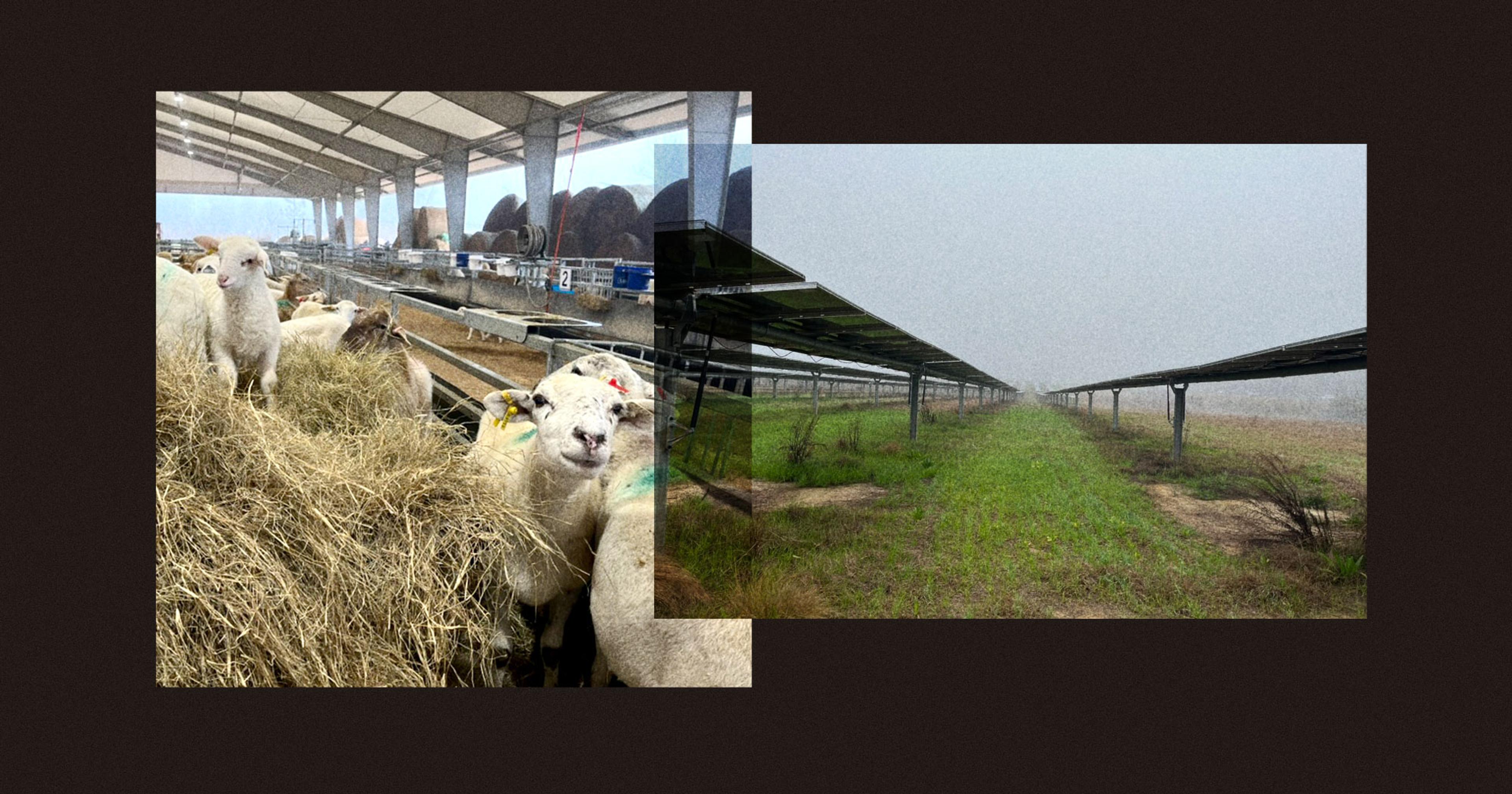

To get the job, they outcompeted a contract usually held by traditional lawn companies, or goats and sheep. Starting their lifespan in a warm room with a heat lamp until their feathers grew out, the flock of 650 spent the rest of their 14-week lifespan under solar panels. Feeders hang under the panels, moved week to week to even out the grazing. The weekend before Thanksgiving, the last batch of almost 150 direct-market fresh birds were processed for local residents.

Turkeys at Carpenter’s WideAwake Farms find shade under the panels and have become part of a dual-use agrivoltaic system, one that integrates solar energy production with food production. The farm has 25 acres leased under a commercial solar operation and manages, via sheep and cattle grazing, an additional 65 acres.

His region faces yearly arguments about the next commercial operation — solar and new data centers — that will be built in New York’s highest-producing agricultural regions. “They like the idea of not using fossil fuels for their electricity, but they don’t like looking at the solar panels,” said Carpenter about his community.

Tompkins County, New York, a renewable energy–forward county, is known for being an early adopter of residential solar, but it’s still finding its boundaries as Central New York is targeted as a key renewable-energy production site. Home to Cornell University, the town sits in a hotbed of research which is also expanding university solar fields, regardless of local public opinion.

Solar arrays make up 7 percent of America power production, with livestock grazing on nearly 130,000 of those acres of production, according to the United States Solar Grazing 2024 Census. But grazing doesn’t stop at sheep.

Evan Carpenter

When he sold off the cows on his New York dairy farm in 2016, Carpenter began leasing some of the land to a commercial solar site, a contract paying enough to gradually cover the rest of his farm mortgage. But he knew farming wasn’t over for him; his next form of farm income would be from the same solar company that is leasing his land, but through a vegetation contract. “Agrivoltaic ideas have gone through my head for years,” he said.

With five years of free-range turkey experience, Carpenter grew his flock and used the land he was already letting his sheep graze on. “We’ve been wanting to have more of a market for them — just haven’t gotten there,” he said. With the help of a 4-H student, 150 birds are being marketed locally and the rest going to a specialty processor.

The data and results of this trial flock will be shared with project collaborators United Agrivoltaics and Cornell University, to study the feasibility and business model of Carpenter’s project to scale dual-use income land.

Caleb Scott, owner of United Agrivoltaics, a company that connects farmers directly with vegetation contracts from solar companies, said farmers are earning the same as landscapers, but with a few added benefits. “They’re providing food off the same land that electricity is being provided off from, and they’re doing a significantly better job than the lawnmowers,” he said.

“It’s natural for a farmer to look at the best way to maximize the use of land. That’s what they’ve always done.”

Around the country, Scott oversees 184 projects and 64,000 sheep. He explained that while sheep are practically custom-made for this work — perfectly sized, docile, shade-loving animals — the turkeys “make it look like a golf course.” Scott also calls WideAwake’s operation the largest turkey agrivoltaic operation in the world.

Poultry grazing is far from common, said Stacie Peterson, executive director of the American Solar Grazing Association. She noted that while the 500 solar sites — 40 percent being utility projects — report using sheep in their vegetation management, “It’s natural for a farmer to look at the best way to maximize the use of land. That’s what they’ve always done.”

Funding and innovation in agrivoltaics is catching up with Carpenter’s operation. The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority recently awarded $750,000 to United Agrivoltaics to explore adding pigs, poultry, and specialty crops at existing solar sites on more than 100 acres. “Farmers are the best site planters for the solar industry. The solar industry just hasn’t figured that out yet,” Scott said.

It’s one of many investments New York state is making in the solar industry, despite a federal shift away from incentivizing renewable energy production. The Trump administration’s political will to reduce renewable-energy protections, combined with Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins’ actions to protect and preserve farmland from solar conversion, has resulted in the end of all forms of renewable-energy tax credits and loans. The decision sent shock waves through renewable business communities, leaving some out to dry.

Evan Carpenter

Projects must be under construction by July to remain eligible for federal tax credits like the Investment Tax Credit and Clean Electricity Investment Credit, which Congress voted this summer to eliminate in the One Big Beautiful Bill. As a result, Scott said, there is now a race to acquire land, install solar panels, and contract solar grazers.

The tax credit cut is anticipated to reduce the amount of renewable projects in the long run, but in the short term, the solar industry is not as concerned. The New York Times reports companies stockpiling solar panels and supplies to show the Internal Revenue Service that their projects are underway. Research firms are also increasing their forecasted wind and solar battery capacity by 10 percent through 2027.

Peterson expects that, even after the tax credits end, there will still continue to be huge growth in the solar industry. “It is the cheapest form of energy,” she said. Her organization is ramping up certification programs with solar companies to take on vegetation contracts, companies that otherwise wouldn’t know livestock can do the job of mowers.

Peterson, who started the agri-solar clearinghouse in the U.S. Department of Energy earlier in her career, has worked directly with livestock grazers since 2018, when ASGA was created. “I watch people in real time change their minds about what possibility there is and what this could be for farmers,” she said.

A 2022 study in Michigan found that over 80 percent of respondents would be more likely to support solar development if it integrated agricultural production. While some argue that ecological and community benefits outweigh methane emissions, overall acceptance of solar still remains contentious.

WideAwake Farms will have even more turkeys next year, farming in a system that may not be common across the country. They are considering more crops into their agrivoltaic system like pumpkins below the solar canopy and apple trees surrounding the property.

“This solar project isn’t seen from the road because of the crops we grow on three sides of it, 75 percent of the year,” said Carpenter. But whether most people realize it or not, Central New York is getting a taste of agrivoltaics this Thanksgiving.