State-contracted range riders assist cattle ranchers in protecting livestock from predators — particularly on the vast stretches of federal land where the animals graze.

In Colorado, thousands of cattle graze upon a salad bar of forage found across 7.8 million acres. It’s one of the many benefits of raising cattle there, where the Bureau of Land Management operates about 2,400 separate grazing allotments used by more than 1,000 ranching operations. Yet, where a plethora of cows once roamed with little worry, much has changed since wolves were returned to the state via a voter-approved reintroduction effort.

Proposal 114 passed in November 2020, making it the first time voters were able to influence state wildlife management strategy. Prior wolf restoration efforts historically followed federal protocol outlined by the Endangered Species Act. When the measure passed, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) had three years to meet the Dec. 31, 2023, deadline to reintroduce wolves into the Western Slope.

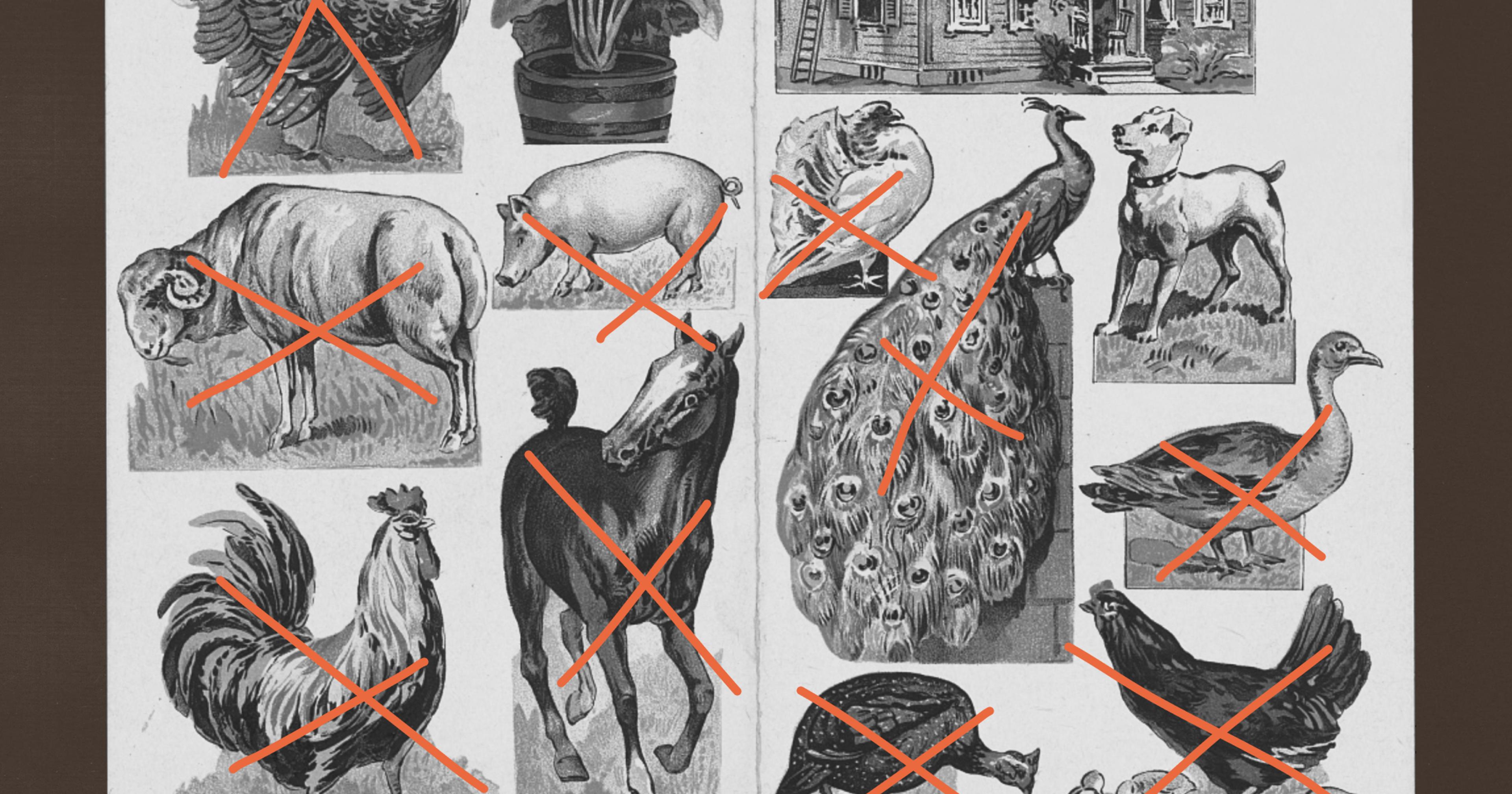

CPW released the first 10 wolves in mid-December of 2023, meeting their deadline. Since then, they’ve introduced 15 additional British Columbian wolves in Eagle and Pitkin counties, and have a goal of introducing 30 to 50 wolves over the next three to five years. Yet, as the reintroduction effort continues, reports of livestock depredation funnel back to both CPW and the Colorado Department of Agriculture (CDA). To date, wolves have killed 36 head of cattle, 15 sheep, one llama and one dog since the reintroduction process began, according to CPW.

“It was a huge change for us,” said Tim Ritschard, a fifth-generation cattle rancher in Grand County and president of the Middle Park Stockgrowers Association (MPSA), which represents producers in Grand and Summit counties where the first 10 wolves were released. “And none of us knew when it was actually happening.”

Enter the Range Riders

Range riders serve as on-the-ground livestock guardians in areas with high depredation. They can travel by foot, on horseback, in UTVs, or by truck, patrolling grazing areas to observe predator-livestock activity, using non-lethal methods — think noisemakers, scare devices, or guns loaded with rubber buckshot or bean bags — to keep wolves at bay. In fact, the use of range riders as predator control was included in the Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan to help ranchers combat livestock depredation. Because Colorado wolves retain both federal and state protections through the Endangered Species Act, it’s illegal to kill them, making non-lethal hazing a necessary component of Colorado wolf management.

Range riders aren’t a new concept to Western communities: “As a producer, most of the time we do our own range riding,” said Ritschard. However, agency-funded ones aren’t the norm. In fact, only two other states have officially funded range rider programs: Washington and Arizona.

“As a producer, most of the time we do our own range riding.”

In 2024, Dustin Shiflett joined CDA as their non-lethal conflict reduction program manager. He has extensive experience in both the agriculture and conservation arenas, having spent 16 years at CPW before spending a year in CDA’s Conservation Division. His first task? Working with local producers, livestock associations, CPW, and other stakeholders to hire the first group of range riders to serve Western Colorado while also developing a statewide range rider training program.

Washington and Arizona’s programs were paramount in helping shape Colorado’s program. He also collaborated with the Western Landowners Alliance, which provides four different Producer Tool Kits for Wildlife-Livestock Conflict Reduction.

“Ultimately, the goal’s to try and get a range rider training program that’ll be considered a gold standard in the Western states and I think Colorado is there,” said Shiflett. “While a traditional range rider might have done livestock management, fence maintenance — general ranch work — the modern range rider deals with wildlife and livestock interaction, mitigation, data collection, predator and livestock movement, and monitoring.”

During the hiring process, Shiplett included the community as much as he could.

“Every step of the way, CDA has tried to involve the producer,” he said. “The approach is more of a what’s going to work best for them because we don’t really know, aside from some of us raising livestock ourselves, what’s going to work best on their landscapes.”

There are currently eight range riders in Colorado, though they have funding for 12, paid via CPW’s “Born to Be Wild” license plate fund.

“Ultimately the goal’s to try and get a range rider training program that’ll be considered a gold standard in the Western states.”

Only months into the program, the idea’s still new. Many producers are skeptical of what the new range riders will do — and why CPW’s involved. Most ranchers don’t interact with the agency on a regular basis, according to Ritschard, who was involved with the hiring process.

That’s where Max Morton, CPW’s wildlife damage specialist, comes in.

“At the beginning, my job consisted of just calling producers all day, every day,” said Morton. “I’d say, ‘Hey, we have some wolves on your allotment. Are you okay with having a range rider out there? We’re not going to mess with your livestock. Just going to kind of make sure the wolves are staying out of trouble.’”

For the past few months, Morton has worked to build relationships within the communities impacted by the new wolf presence, noting how grateful he is to be “allowed on their properties to try to make the best of what they would call a bad situation.”

“I’m really happy to see the collaboration and the togetherness even in times of such stress,” said Morton.

Ride, Ranger, Ride

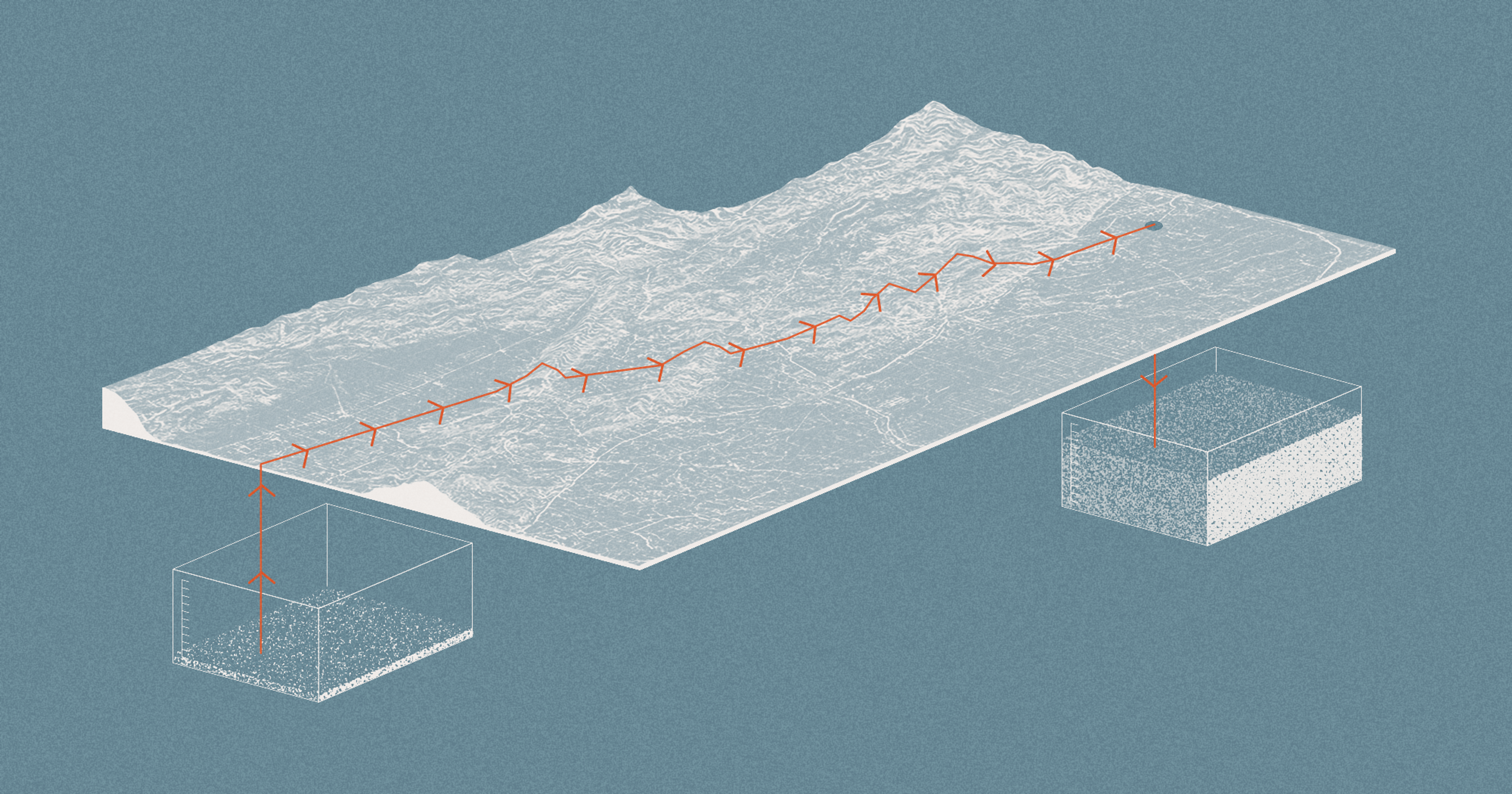

Unlike the old-fashioned depictions of range riders in Western imagery and paintings, those filling the positions have modern technology in their toolkits, which makes managing hundreds of thousands of acres by only eight contracted range riders manageable. With GPS collars on nearly 100% of the state’s wolf population, range riders know where the wolves are at all times — and can keep tabs on traveling packs.

And CPW anticipates the population will naturally increase. In July 2025, the agency confirmed three new packs — the King Mountain Pack in Routt County, the One Ear Pack in Jackson County, and the Three Creeks Pack in Rio Blanco County — though the exact count isn’t yet known. Female gray wolves average four to six pups per litter; however, pup survival rates vary based on location, with survival rates for the first year between 50% and 60%, according to CPW. The average lifespan of a wolf living in the Rocky Mountains is only three to four years.

“We’re coming to the tail-end of the denning season,” said Morton, noting that wolf pups are typically born in late April, sticking to their dens until the pups are about eight weeks of age “That kind of heavily localized wolf presence has really allowed our range riders to establish perimeters and work pretty closely with the producers who are in the immediate vicinity of highly localized wolves.”

“We want to give producers some peace of mind that somebody’s out there monitoring their livestock from predation.”

While it doesn’t seem like a lot of riders, Morton added “given the biology of the wolves and the number that we have in the state, coupled with the technology that we have to our advantage, we’re making it work pretty well.”

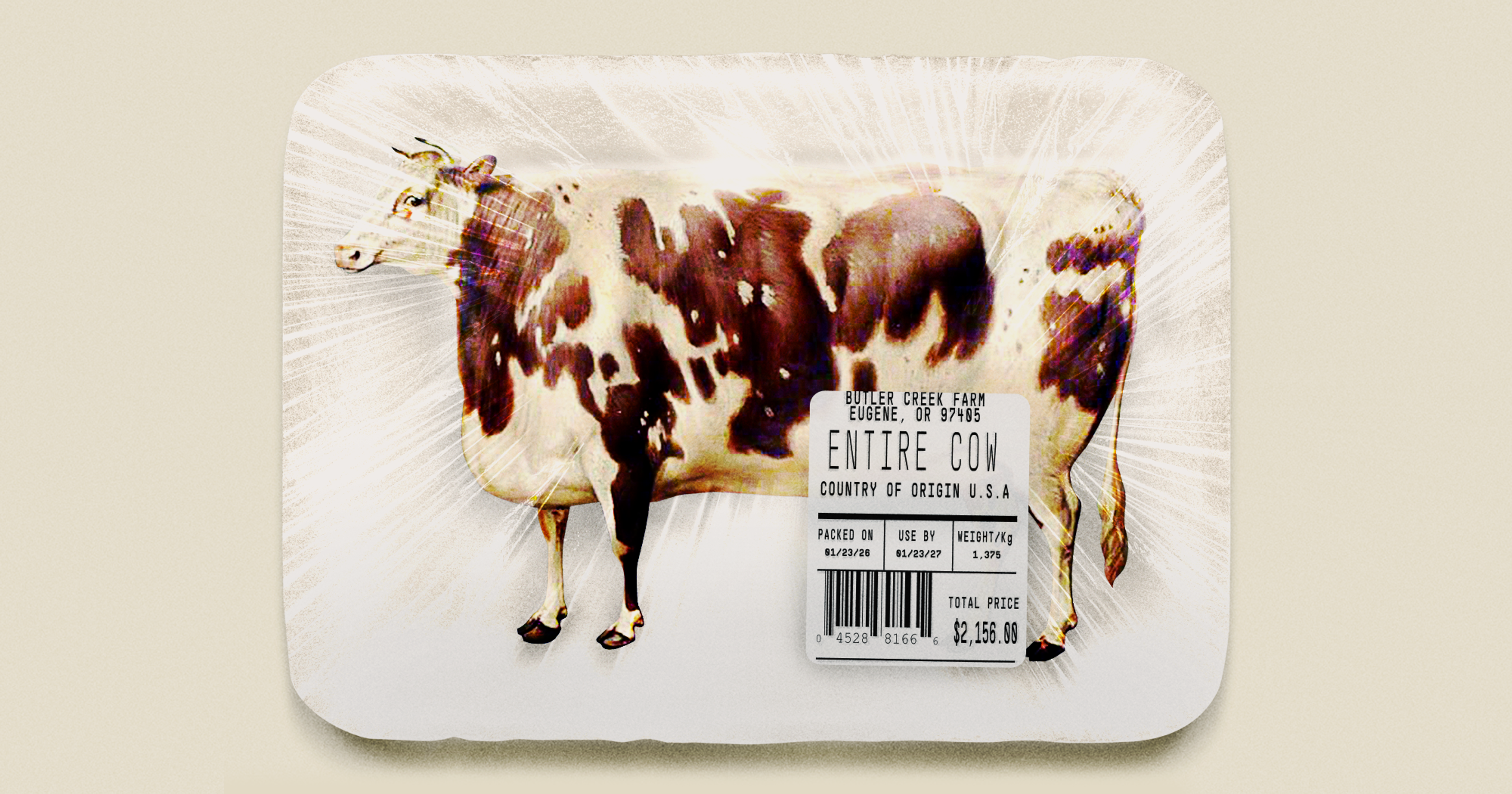

To measure success of the program, CPW will be collecting data, including GPS coordinates at range rider locations to compare with wolf presence, location of carcasses, wolf tracks, scat, and hair to see if range riders do decrease depredation for local producers. The state will compensate producers for lost livestock, up to $15,000.

As for the length of the program, Shiflett said the on-the-ground program will likely run seasonally — April through October/November — due to Colorado weather patterns with additional range rider training occurring during the offseason.

“Hopefully, we’re being effective out there,” said Shiflett. “We want to give producers some peace of mind that somebody’s out there monitoring their livestock from predation.”