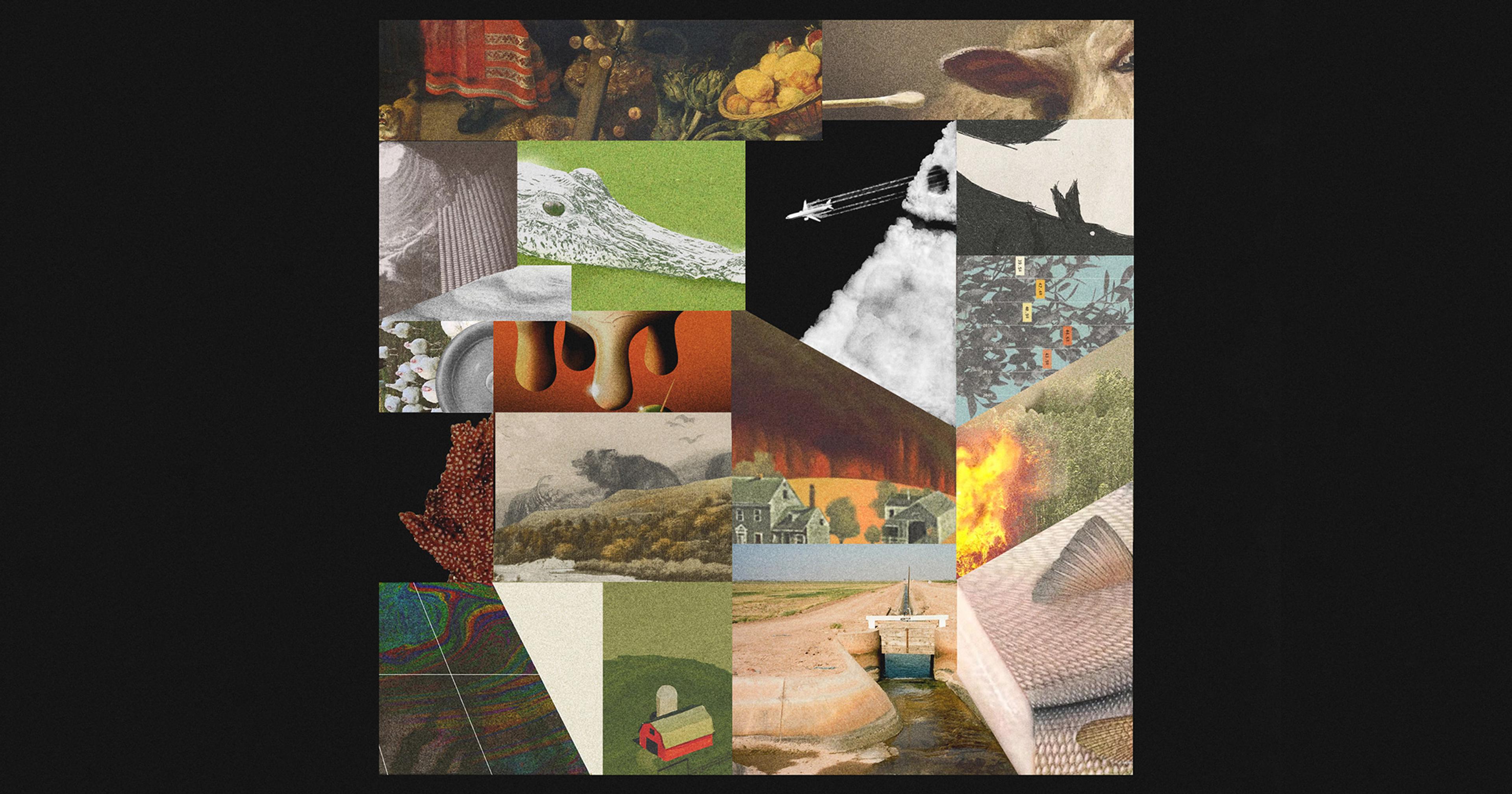

How long can the agriculturally vital San Luis Valley hang on to its biggest asset — amid waves of existential threats?

This southern Colorado valley is dry and dusty. The sun bakes the topsoil relentlessly, and powerful winds haul up from the West grabbing sand as they go, depositing dunes on the eastern flank. The center-pivot circles of potatoes growing along its 100 by 50-mile expanse are dots of color on a muted palette. When I need to run errands I make a day of it, driving hours in various directions to get to a Home Depot or a Target. In between the San Juan and the Sangre de Cristo mountain ranges, there’s not much other than a handful of small towns and a lot of agriculture.

Underground, though, the San Luis Valley has something that much of Colorado lacks: water.

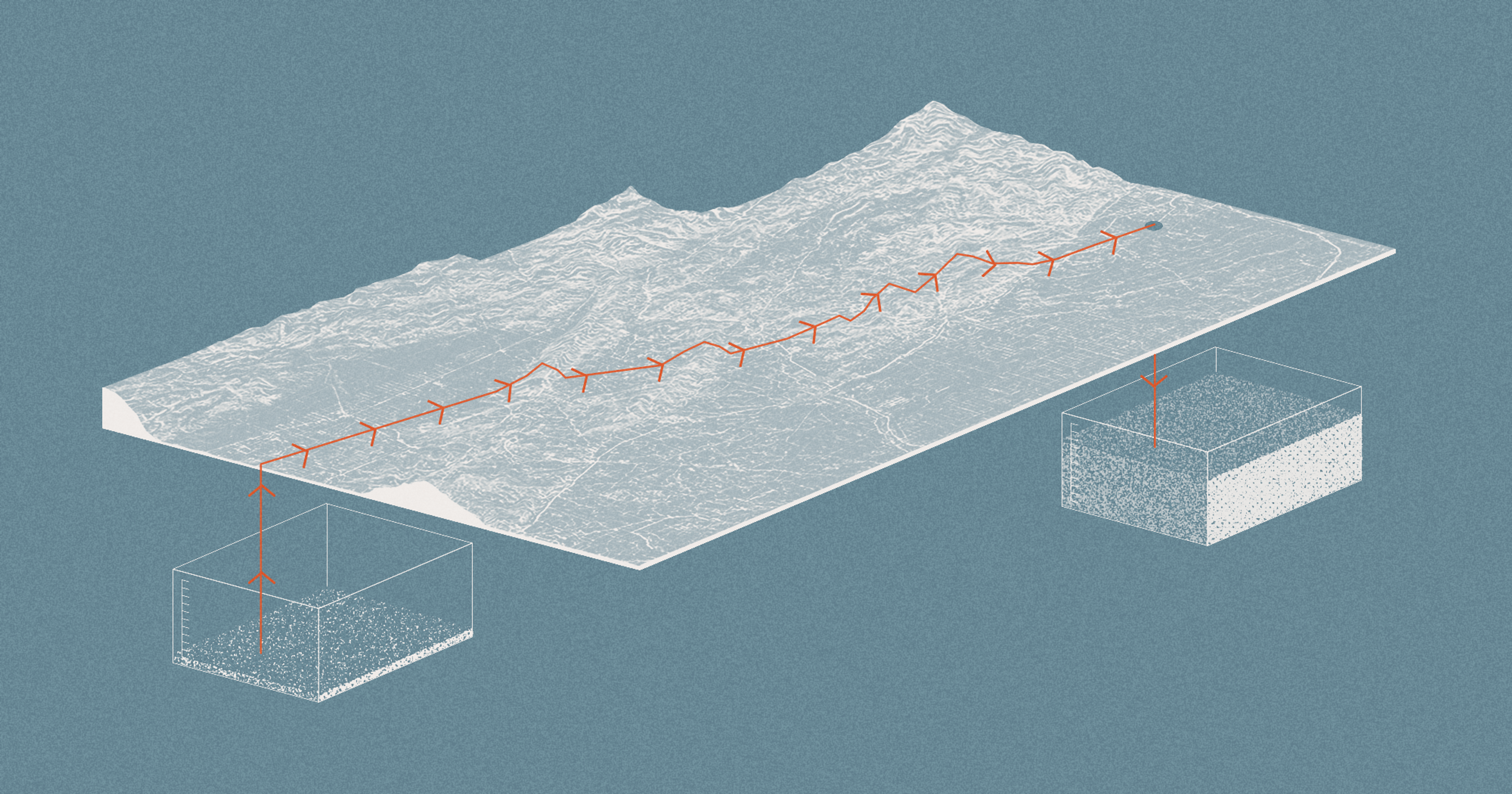

South of the Saguache-Alamosa county line this groundwater feeds the Rio Grande as it flows out of the mountains and heads for New Mexico. But to the north, the water that runs off the western flanks of the Sangre de Cristos sinks into a closed aquifer, which irrigates farms and ranches and the largest cooperative cannabis park in Colorado, as well as drinking water for Saguache County.

I moved here in 2021 as a compromise. I wanted to farm peppers; my partner wanted to climb mountains. This was an alright place to do both. The swath of 14-thousand-foot peaks that lines the east side of the valley like a massive predator-proof fence was the first thing I noticed when we arrived.

The second thing I noticed was the ubiquity of the protest stickers. “RWR,” they read, protesting in black letters with a big red circle-and-line superimposed on top. They’re on trucks and EVs; they’re taped up on windows of local stores and slapped on the backs of stop signs. You can buy them for a couple of dollars at local retailers across the valley. It didn’t take me long to corner a neighbor who sported one and ask her what the deal was.

“Oh, that,” she said, before explaining. “They’ve backed off for now, but not for long.”

RWR stands for Renewable Water Resources. The group is spearheaded by former Colorado Governor Bill Owens and his chief of staff Sean Tonner. Their goal is to purchase enough water rights in the San Luis Valley to pump 22,000 acre-feet of water from the aquifer and pipe it northeast, over several mountain passes, to Douglas County, a rapidly growing suburban area south of Denver.

The project, its proponents state, would be beneficial to our local economy. The “benefit”? Water rights purchased at a premium from local farmers, at the cost of their irrigation systems. It would provide drinking water to an area of the state that is growing unsustainably, with houses built faster than the county can provide resources for them.

The San Luis Valley is a quiet place, with a light reputation for weirdness. We have a UFO watchtower and an alligator rescue. Hot springs bubble up all over. We’re home to the Great Sand Dunes National Park, a beachy landscape that looks very out of place in the middle of the high country.

Maggie Gelbwak

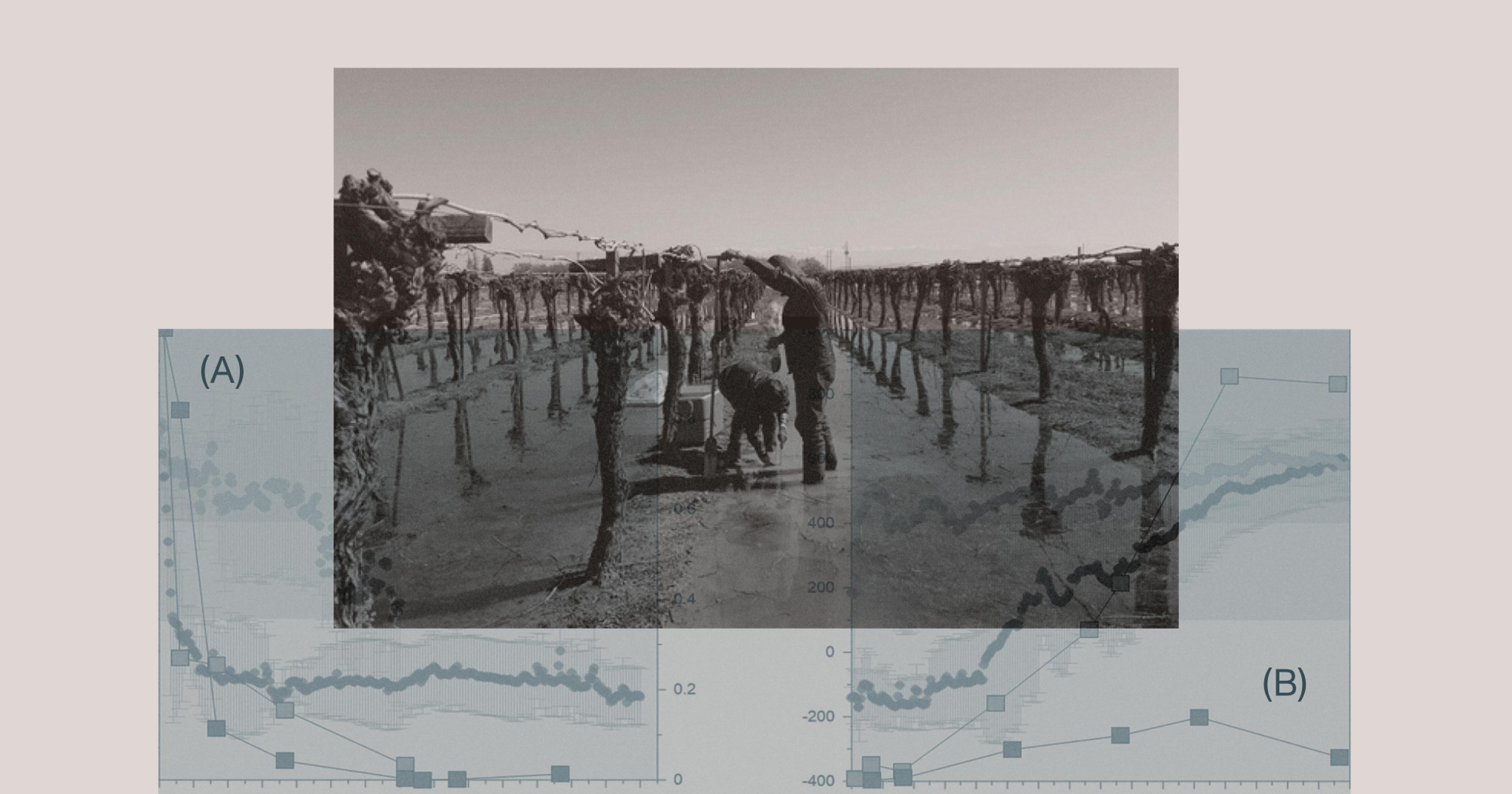

A lot of food grows here. The sunshine makes it a perfect location for sunflowers. Decades ago, lettuce and barley were the biggest exports, but potatoes became king due to the sun, the soil, and the giant aquifer. There’s no lack of animals, either. Herds of cattle graze between the farms, interspersed with yak ranches, goats, and bison.

It’s also poor. Poverty rates here are estimated to be over 21%, and two of the counties that make up the valley grapple with persistent poverty. Other than tourism from the Dunes and the annual sandhill crane migration, there’s not much fueling the economy outside of agriculture irrigated by the aquifer.

Colorado’s water rights are governed by prior appropriation. “First in time, first in right,” the state calls it. This means that whoever was granted their right to water from a certain stream or river last is the first to lose it if the stream’s volume decreases.

For this reason, farms with older water rights are worth a lot of money. And if a farmer in Colorado wants to make some cash, selling those water rights — or leasing them for a royalty — can net a significant amount.

The Colorado River Compact, written in 1922, allocates the water moving through that basin into equal portions for both the Upper and Lower river basins. In times of drought it requires the Upper division to send “one-half of the deficiency” down to the Lower division. And it mandates that usage by Upper division states — Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming — cannot cause the river’s flow to be depleted below a certain amount for the states downstream.

At the time of the compact’s signing, there were no provisions in place for things like megadrought, environmental conservation, or the fact that the writers of the Compact were misunderstanding the amount of water that flows down the Colorado River every year.

People have been living and farming here for longer than the State of Colorado has existed.

The Colorado River is on the other side of the continental divide from the San Luis Valley. But the ripple effects of the Colorado River Compact echo throughout Colorado’s landscape. Every year that the drought gets worse, cities along the front range find themselves at risk of water shortages. Douglas County is made up of these cities: wealthy suburban neighborhoods, bedroom communities for Denver and Colorado Springs.

RWR seeks to solve these drinking water woes. As Douglas County grows, its population will need to harvest water from somewhere. The South Platte River, which flows out of the mountains through Douglas County, is already tapped by states and municipalities to the east and north.

The humble aquifer underneath the San Luis Valley, though, seems like a massive deposit of water for a comparatively small population. And because of the physics of the closed aquifer, this water doesn’t really go anywhere. One could be forgiven for imagining that it’s not already being used.

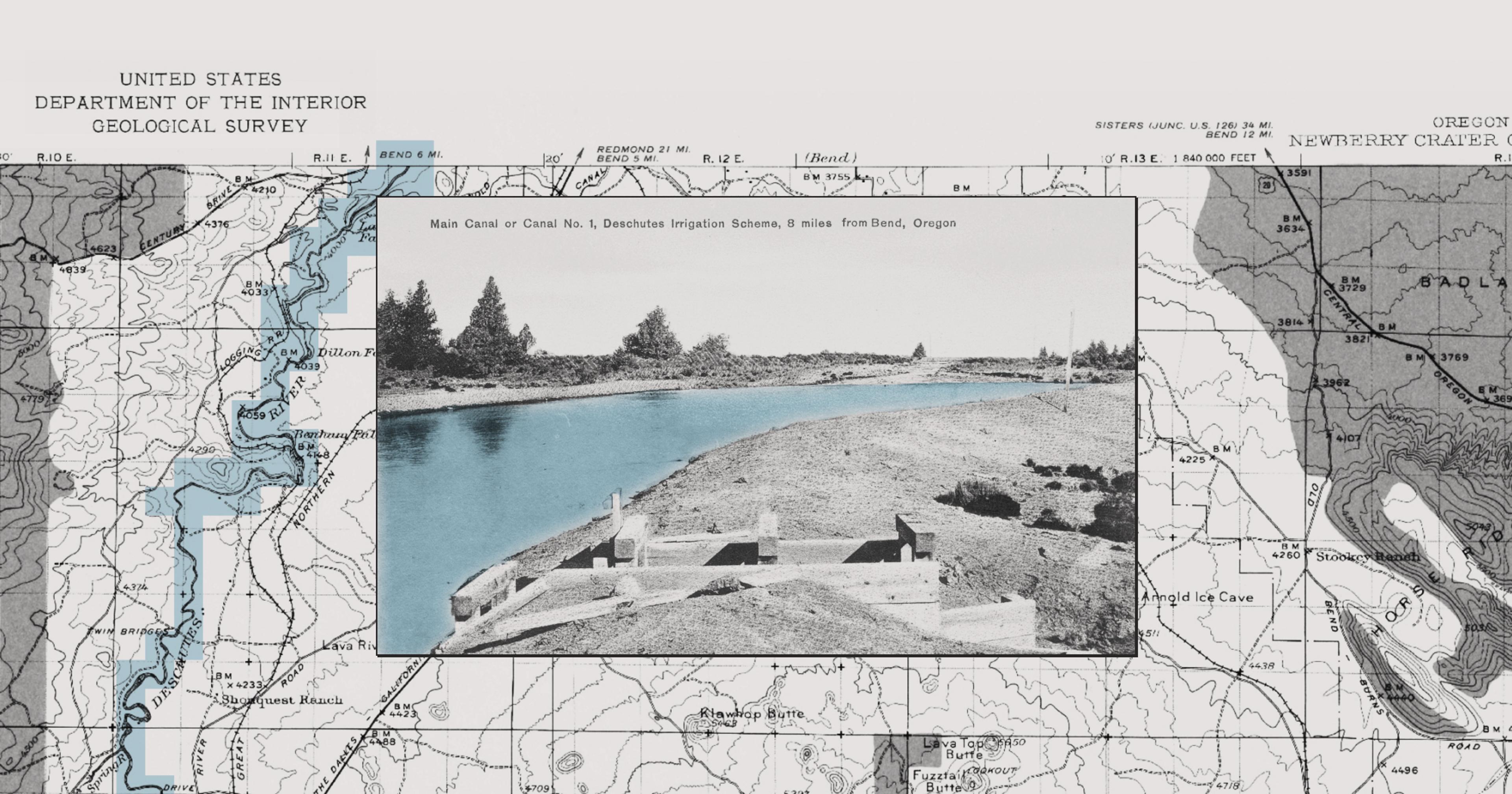

People have been living and farming here for longer than the State of Colorado has existed. People have been speculating about the valley’s water for just as long.

Before there was RWR, there was a group called American Water Development Inc. In 1986 AWDI applied for a permit to pump water from the San Luis Valley and pipe it over the mountains to Denver. After a long legal battle, which included testimony from geologists and conservationists about why the plan was impractical at best, the permit was denied. Now, 40 years later, a different former governor and a different water speculation group wants to try the same thing.

“The water security challenges in the Valley are difficult enough as is and the consequences of shipping water out of the Valley just exacerbate the challenges exponentially,” said Republican state Senator Cleave Simpson, a fourth-generation farmer and rancher and San Luis Valley native. “Not good for our community and not good for the state of Colorado.”

In a rapidly aridifying American West, every drop of water is precious, and none of it is affordable to lose.

There’s very little local support for the project in the San Luis Valley. There’s no pro-RWR version of that bumper sticker that’s so ubiquitous around here. Even on RWR’s website, the only praise they can advertise is damning: “When people learn about the full project, local support climbs to more than 42 percent.”

I asked around at the local market and at the post office, to see if I could find someone who would give me a positive quote about the project. Nobody could. The most common sentiments I heard were indignation and bewilderment. Sure, RWR would offer landowners a premium when buying the rights to their water. But at the cost of depleting our own resources, it doesn’t seem worth it.

“Our agricultural producers are already facing incredible long-term drought and over pumping,” says Liza Marron, Saguache County Commissioner. “We surely don’t need to… sell our water out of our basin and end up relying on a prison economy to survive.”

If the water gets diverted, the farms suffer. If the farms suffer, the valley suffers. It’s a simple equation to those of us who live here. Already drought worries us. In recent years the snowfall is below average, and the snowmelt coming down the mountains decreases in kind. The San Luis Valley’s annual precipitation is some of the lowest in Colorado. The aquifer’s ability to replenish itself from surface water is starting to come into question.

In 2022, Douglas County rejected RWR’s pump-and-pipe proposal. The county’s attorneys “…said the proposal did not comply with the Colorado Water Plan, which favors projects that don’t dry up productive farmland and which have local support.” Within a year, RWR began funding candidates for one of the county’s water board elections, donating tens of thousands of dollars to an election that usually sees candidates self-fund for far less. And now, Sean Tonner, one of the principal investors of RWR, has been appointed to Douglas County’s new water planning commission. While the proposal itself has been shelved, the group is still working, and there are sure to be new developments as demographics and governments change.

What is the worth of a rural agro-economy? When do the wants and needs of a metropolitan area supersede those of the people and the landscape far away from it? The aquifer underneath the valley is already in use: by potato farmers, by cannabis growers, by locals with their vegetable gardens and the elk and sandhill cranes. In a rapidly aridifying American West, every drop of water is precious, and none of it is affordable to lose.

It’s easy for Valley locals to turn up their noses at the Douglas County prospectors, to tell them to get water from their own aquifer, but they have none. Someone will eventually have to share.