I

Turning onto a country road, I had the uncanny experience of being in two places at once. On the left side of my windshield yawned the moonscape of the New Mexico desert, a mesa of shifting dust and rock with a sprinkling of parched sagebrush. But on the right spread a canopy of trees: cottonwoods, mulberries, thickets of wildrose, and the occasional juniper. This road, on the outskirts of the northern New Mexico town of Española, seemed to exist in two different worlds, one lush and abundant, one desolate and dying.

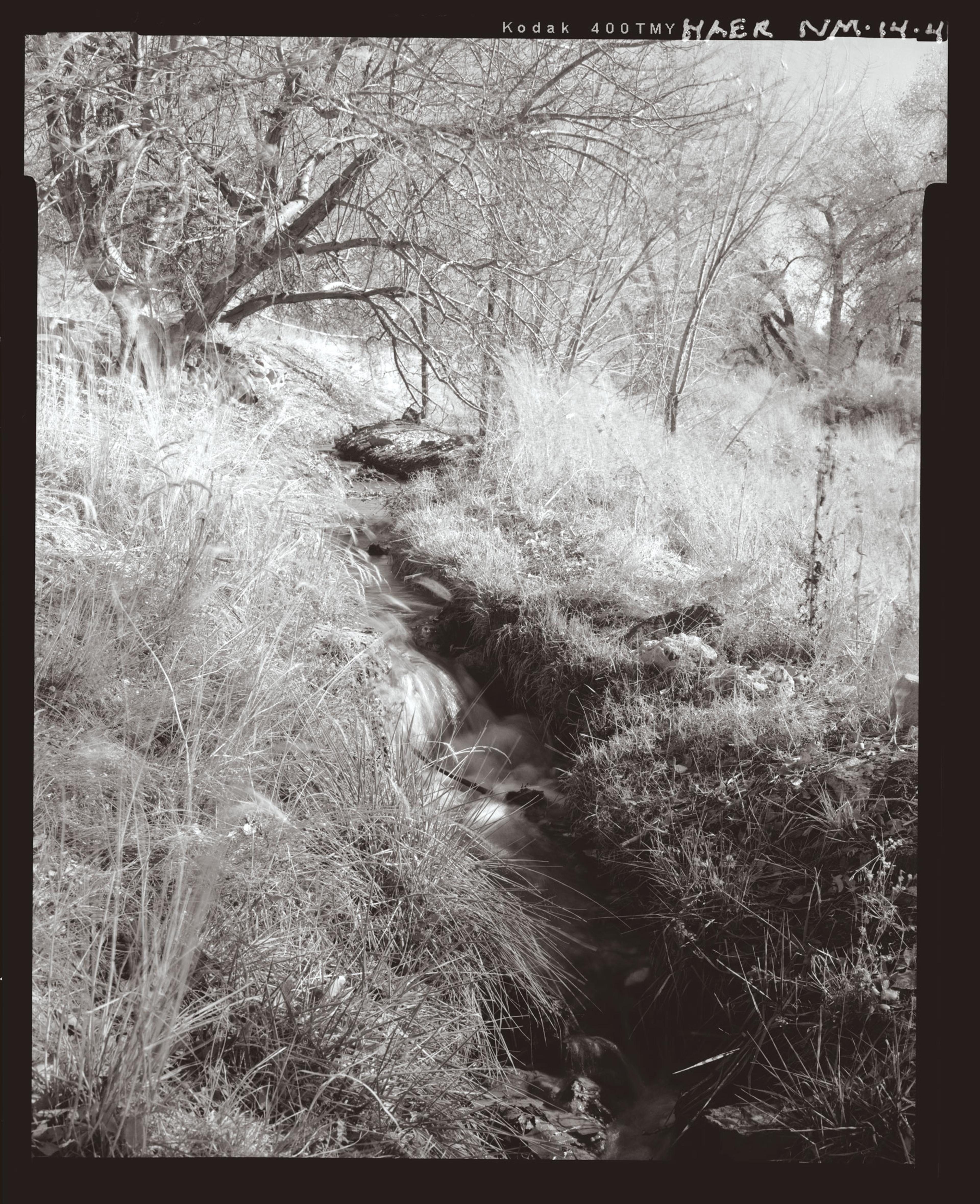

It wasn’t until I turned into Rick Martinez’s driveway that I understood why. Under the thick canopy of trees on the right, water flowed, muddy and calm, through a four-foot wide creek. It looked every bit a streambed shaped by water, earth, and time. Which it is, but with one additional, vital ingredient: community.

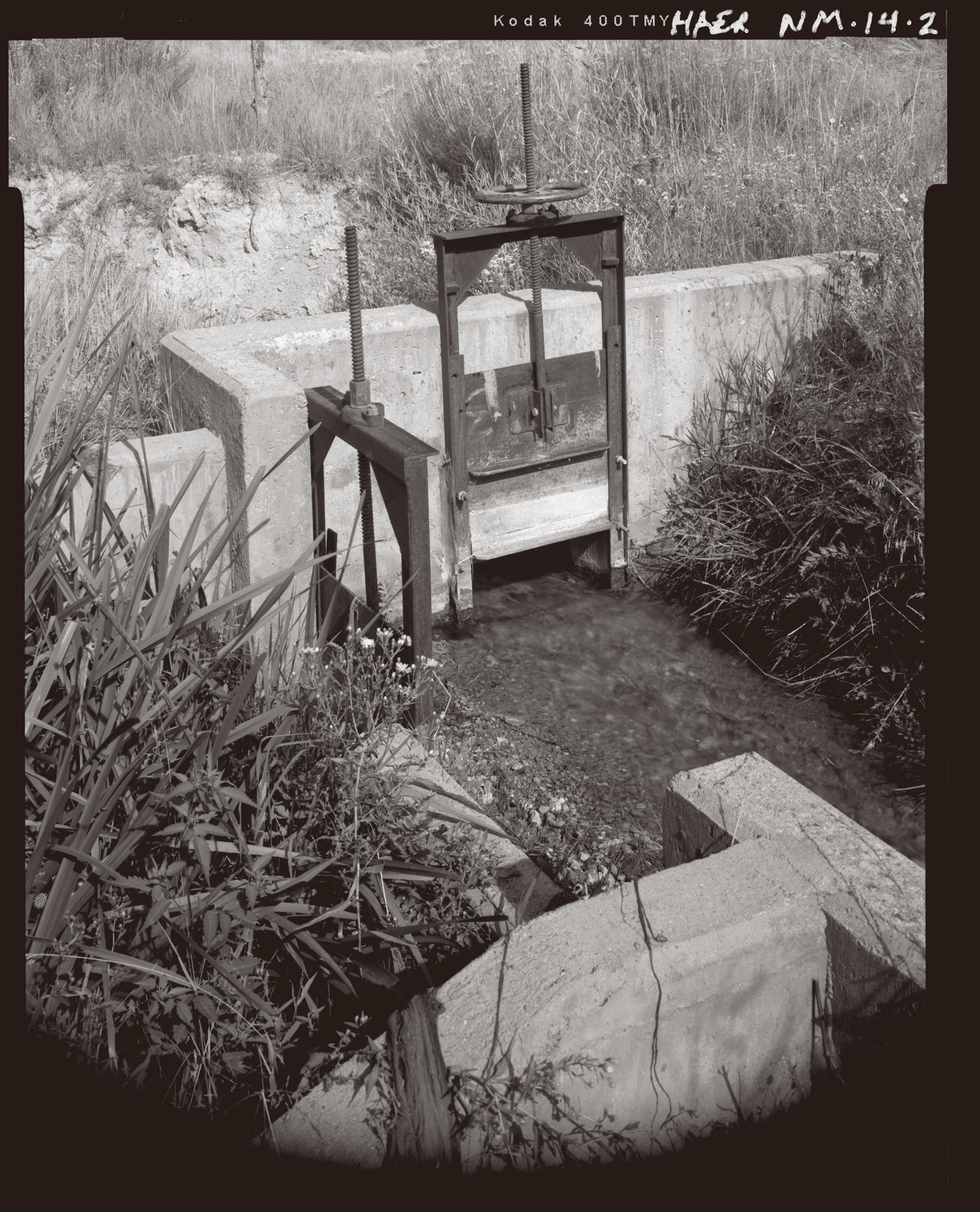

Rick met me in the driveway of his small farm, excited to tell me everything he’s learned in the seven years he’s been an active irrigator on the Salazar Ditch, that creek I’d just crossed. This particular acequia is one of the 22 Rio de Chama Acequia Association ditches, a series of hand-dug and community-managed irrigation systems along the Chama River. The association collectively holds the second-oldest water right claims in the nation, after Indigenous claims. This ditch was dug around the year 1600, and has been maintained and operated by one of North America’s oldest continuous democratic institutions ever since.

Rick’s role in the acequia is twofold: He’s a commissioner, partially responsible for some decision-making and administration, but more importantly he’s a parciante, a holder of a right to a share of the acequia water. Parciantes aren’t just physical irrigators, they also have voting power — they elect their leaders and must agree to collective decisions. In the past, parciantes remained in good standing by providing peons, workers, but today few ditches require parciantes themselves to clean the ditch in the spring or make repairs during the summer irrigation season. Dues now act as a substitute for work, and annual fees are used to hire backhoes.

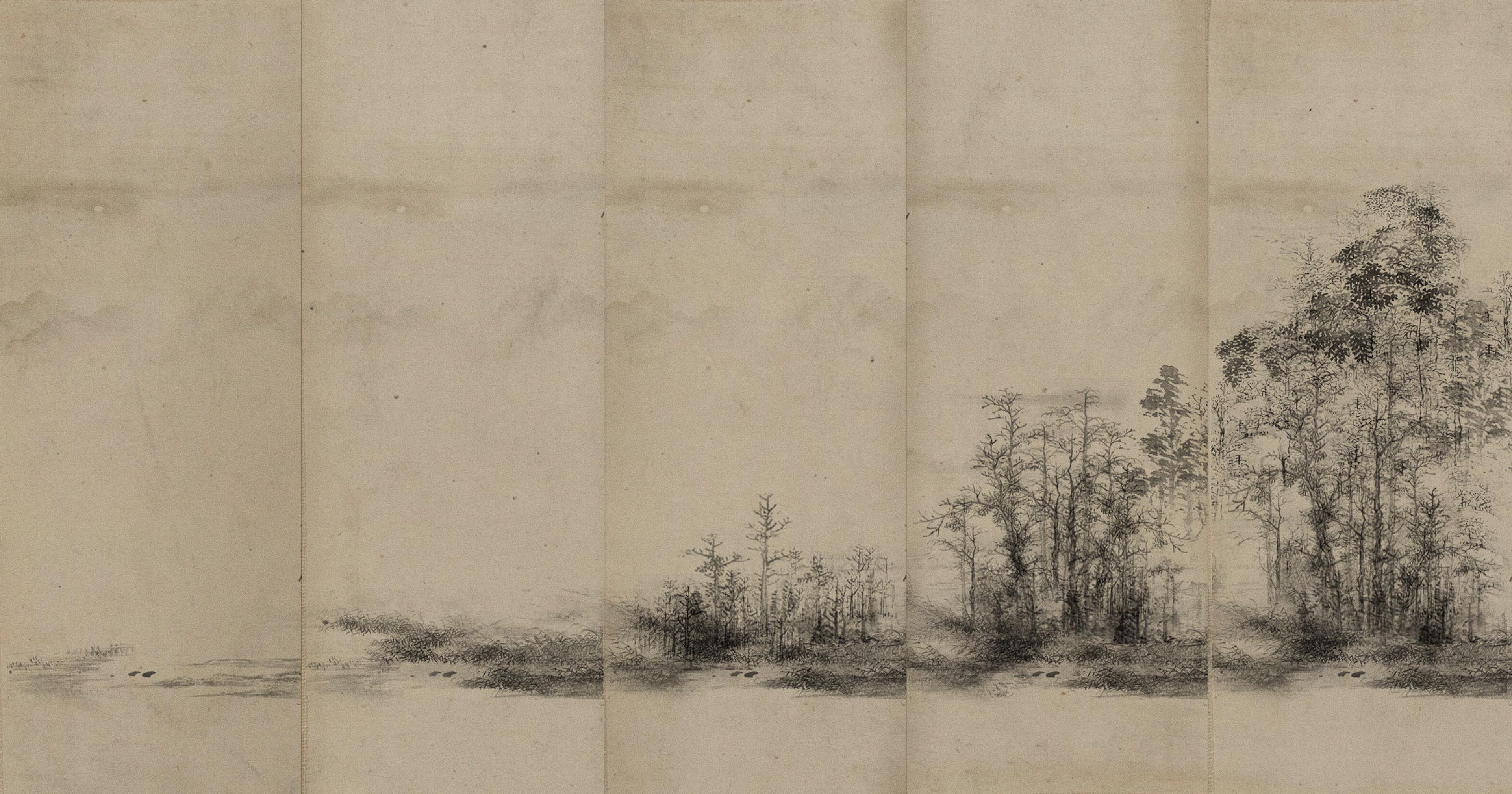

The Salazar Ditch is just a few miles long, with parciantes numbering in the dozens. And yet farmers along this acequia use the river’s meager flows to turn riverine lowlands into agricultural oases. In the space between the acequia and the river, the high desert is transformed from bare rocks and scrubland into pasture, orchards, bean and chili fields, the odd lawn and flower bed. Even more striking is the non-agricultural landscape, the cottonwood stands, the quaking aspens, the thick brush dusted with flowers and berries. Most years, there is water for all. Beyond the acequia, desert stretches to the horizon.

II

For most of human history, if you wanted to build a city that lasts, the middle of the desert was your best bet.

Today, many look at cities like Phoenix, Las Vegas, Albuquerque, even small towns like Española, and marvel at the stupidity of putting down roots in the parched terrain of the American Southwest. But to our oldest agrarian ancestors, nothing would have made more sense. First, if the aim is to settle and become dependent on labor-intensive, sedentary crops, your nomadic, pillaging neighbors just might show up for a raid at harvest time. Thus, having a hot, desolate desert barrier is a powerful security measure for farming communities. Second, many food crops thrive under bright sun and suffer from disease and insect pressure in moist conditions. Deserts have plenty of the former and much less of the latter, so as long as humans supply water, many plants thrive in desert conditions.

In the desert, of course, water rules. Desert civilizations rely on rivers for every aspect of their existence, but most importantly — to feed themselves. Irrigation was an early follow-along of the agricultural revolution, but how to bring the river everywhere that needs water, and do it fairly and effectively, is still very much an open question.

Nowhere has the debate raged more fiercely in the U.S. than along the banks of the Colorado River. This 1,450 miles of liquid property stretches from the Wyoming Rockies all the way to Baja California, watering much of America’s high and low deserts with the melted snow of countless mountaintops. The flows rushing through this artery, like the waters of the Nile and the Tygris, don’t whisper about the agricultural possibilities they can support. They roar.

People in the Southwest have responded to that call since time immemorial. This region boasts evidence of some of the earliest North American civilizations and today, Pueblo peoples carry on that legacy of Indigenous settlement. Europeans heard the call too, first the Spanish, then Euro-Americans. John Wesley Powell — the famed Colorado River explorer — and his contemporaries saw the river and marveled at the tremendous opportunity it promised.

To unlock that promise, today we hand over as much as 80% of the Colorado to cultivated plants and animals. We do this in many ways, but mainly we pump water out of the river using fossil power, and haul it across the desert in pipes, hoses, or cement-lined ditches. The aim is that not one drop be diverted to a non-right holder. Once this water arrives at its destination, often dozens or hundreds of miles from its source, the crop is watered: by sprinkler, drip hoses, or open pipes that flood water along rows of lettuce, alfalfa, or cotton.

From this distant, shrinking river, plants drink, and what remains sinks into distant underground water tables. Or, more likely, it disappears into the blinding white air.

III

Acequia is a Spanish word, borrowed from Arabic, as Spaniards learned the practice of carving their own streams from the desert-dwelling Moors. And there was a lot to learn — the engineering required to build your average acequia is stunning, a fact I learned from Don Bustos, who farms on the other side of the Española Valley from the Salazar Ditch.

“400 years ago, someone stood here,” he told me, gesturing around at his farm, perched on a hillside overlooking the Rio Grande Valley, the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in the distance. “They said, ‘There’s the Rio, but we’re going to go to the Santa Cruz River, and dig a seven-mile long ditch using hand tools, getting the water to travel north in some places, to bring it to this land.’” Such an endeavor took considerable ingenuity, but also a village’s worth of labor to create and maintain it — a resource truly by the people, for the people.

Today, New Mexico’s state constitution formally recognizes the autonomy of acequia associations, and that recognition, along with centuries of community organizing, has helped to keep water flowing into more than 700 ditches across the state. Though acequias once existed all across the Southwest, those found in neighboring states never received the same level of recognition; most have faded from memory.

A saving grace of New Mexico’s acequias is that they mostly draw water from the Rio Grande and its tributaries, rather than the Colorado. The Colorado is, even in the heart of the Arizona desert, a monstrous being, disgorging around 22,000 cubic feet of water per second. The Rio Grande, at its fiercest, holds about one-tenth of that. But New Mexico’s relative water poverty has likely shielded it from the periodic blue-gold rushes that have plagued its western neighbor. There’s simply not a quantity of water worthy of waging billion-dollar, decades-long, multi-state wars over.

Beneath the notice of economic giants, an entirely different way of thinking about water and farming survived along rivers and creeks like the Chama and Santa Cruz and Rio Grande. And as climate chaos advances into what is already the hottest and driest region of the country, acequias stand as a reminder that our newest ways of thinking about water are neither the only nor the best.

Take, for example, the governing principle of Western water law, the prior appropriation doctrine, the “first in time, first in right” idea that, as John Oliver once quipped, is basically an elaborate system of “dibs.” This principle essentially provides senior rights holders the most significant and secure access to water, ensuring that if your ancestors occupied a geography first, you would be the last forced off the land due to drought (though for the last two centuries, those Indigenous groups with the oldest claims of all were, naturally, excluded). Prior appropriation is a very practical legal principle, or it would be, if humans were perfectly rational economic actors with no sense of community or desire to work, live, and connect with others.

The acequia system offers an alternative. The principle of repartimiento, or shortage sharing, requires parciantes themselves to determine how much everyone will cut back to ensure that water still flows all the way through a given ditch and back into the river. The repartimiento schedule might be drawn up by leaders, but it has to be approved by a quorum of the association. Similar rationing plans are negotiated between acequias who share the same river. Without a doubt, shortage sharing can be a fraught business, sparking inter- and intra- ditch feuds that span generations, leading at times to folkloric levels of conflict. But in the end, the gravity of acequias, with their historical and physical ties that bind parciante to parciante and community to community, has for centuries outlasted droughts and dam-breaks, floods and fistfights.

It’s vital to note: Water in the acequia is used by the parciantes, but it is not owned by them. In the North African desert, where acequias originated, to deny a person water was tantamount to murder. In such a tradition, water is the right of all. So parciantes own the ditch, that parabola of empty space a few feet deep and a few miles long, and have a right to some share of the water that flows through it — which is not assumed to be a fixed, annual amount. A share of the water requires a share in labor costs and shortage, and how exactly that sharing works is a question that parciantes must decide together.

A few hundred miles west, the legal doctrine that has governed the Colorado River for less than 200 years is already starting to unravel. The river states have spent much of the last decade playing a high-stakes game of chicken over sharing an ever-depleting quantity of water, while the lives and livelihoods of tens of millions of Americans and Mexicans hang in the balance. Already, individuals, states, companies, and even nonprofits are sniffing around the edges of Western water law, looking for loopholes and technicalities that will allow them to buy water rights, stockpile them, and generally profit from future water scarcity.

It’s telling that even Powell, the Euro-American who did more than anyone to bring attention to this region, believed that the only way humans could flourish in the Southwest was if water was managed by its users, at a relatively local level. Powell returned from one of his final expeditions with a map of the West, divided, as he envisioned it, into dozens of states where today we have fewer than ten. Powell’s states’ borders followed watersheds, proposing to unite highland timber users, mid-altitude grazers, and lowland farmers and cities both politically and aquatically. Together, he believed, watershed-bound communities that share a common resource could negotiate through scarcity. He also prophesied that creating boundaries that arbitrarily split watersheds between states would lead to nothing short of a “heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights.”

IV

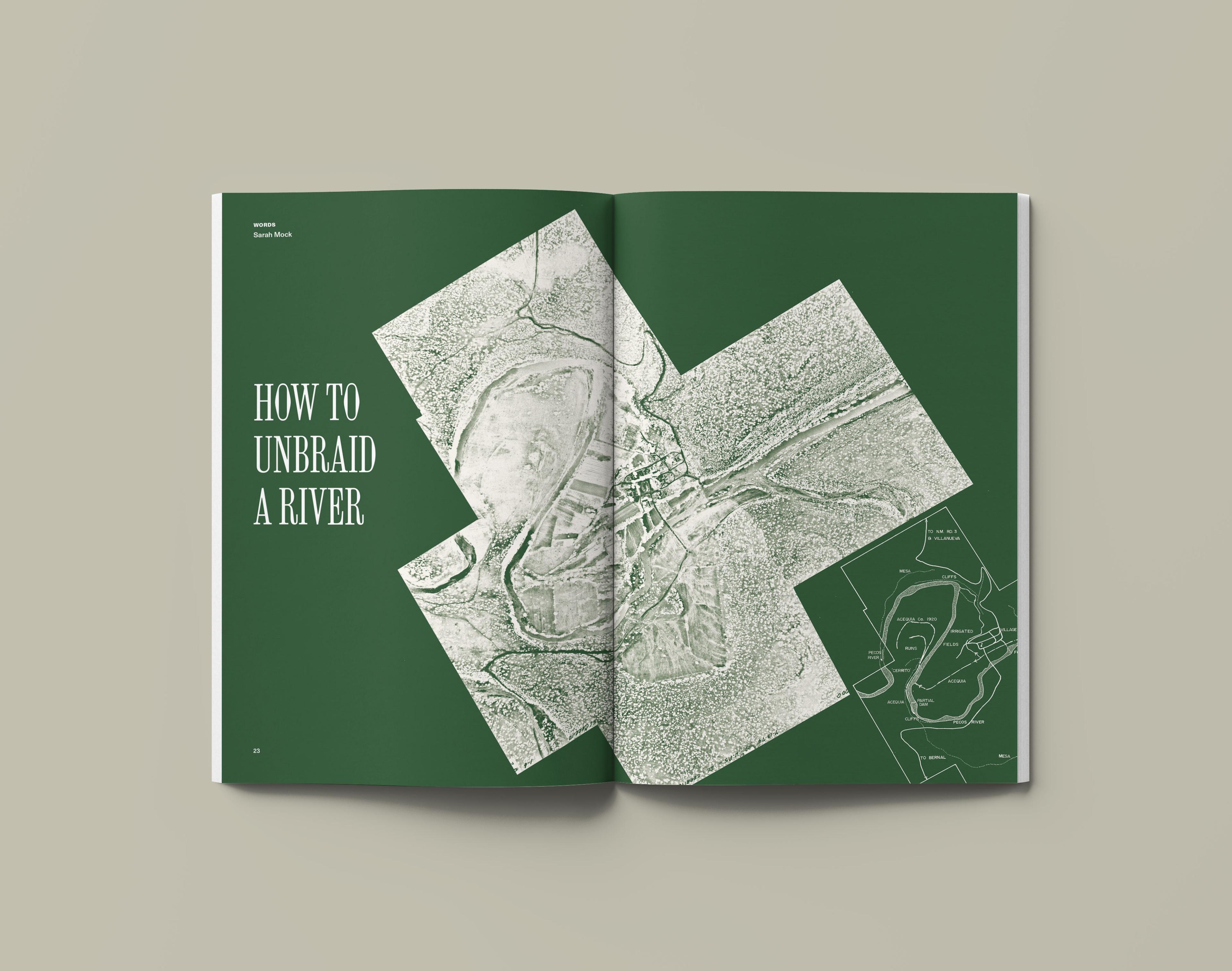

Downriver, far below where the Salazar Ditch rejoins the Chama, and the Chama and Santa Cruz reach the Rio Grande, the Arenal, Armijo, Atrisco, Los Padillas and Pajarito acequias are like unbraided threads of the Rio as it winds through the Atrisco land grant. The land grant, along with two adjacent grants, are part of the wider Albuquerque area that could best be described as the opposite of ex-urban (perhaps in-rural?), consisting of swaths of farmland and countryside intermixed with strip malls and fast food joints, a mere ten minutes from Albuquerque’s skyscraping downtown.

“For a long time here in New Mexico, we have existed within a clash of civilizations. On one side, we have our farming traditions, our culture, our ways of participating with the land and water and each other. On the other side is industrialization.”

Jorge Garcia has done much to preserve and rehabilitate the land grant acequias as part of his work as the founder of the Center for Social Sustainable Systems, which aims to preserve the traditions and science-based practices of local and Indigenous communities related to land and water. He does this work because, despite their long history and relative success, many New Mexican acequias are struggling. Not for lack of water, but lack of community participation.

“For a long time here in New Mexico, we have existed within a clash of civilizations,” Garcia said. “On one side, we have our farming traditions, our culture, our ways of participating with the land and water and each other. On the other side is industrialization, which requires the state to come and distribute the resources.” When it comes to water in an industrialized worldview, Jorge argues, people assume that the state acts on their behalf and in their best interest.

But how can the state, Garcia challenges, simultaneously act in the best interest of an Española parciante, an Albuquerque city-dweller, and a southern New Mexico mine operator? We all need water — more all the time — and the quantity is limited. Like a painful game of rock-paper-scissors, the questions go round and round. Does an ancestral claim to water for subsistence agriculture outweigh the hope of new mining jobs in an economically depressed region? Does the need for clean drinking water in a growing metro area outweigh the demand of thirsty industrial uses? Which state bureaucrat could possibly decide whether it’s more important to honor our past, enjoy our present, or invest in our future?

These questions are being answered across the Southwest, and as always, the conclusions are vigorously and bitterly disputed. Blood runs thick and hot in these deserts, where rivers flow not along boundaries, but through the heart of the problem. Acequias don’t offer a silver-bullet solution, but they do offer a human-scale avenue to address them, which in turn creates space to account for things we value beyond dates on land deeds.

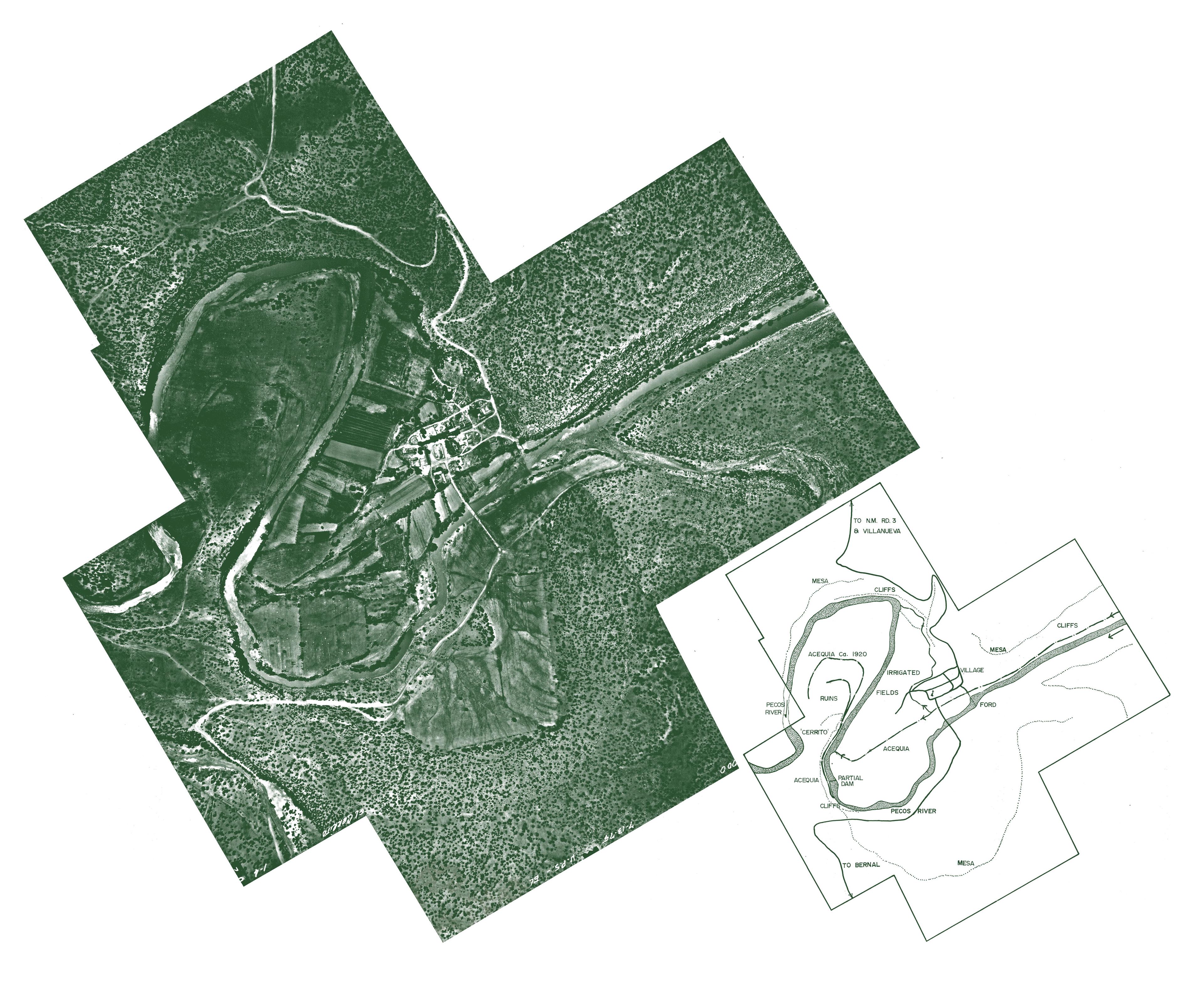

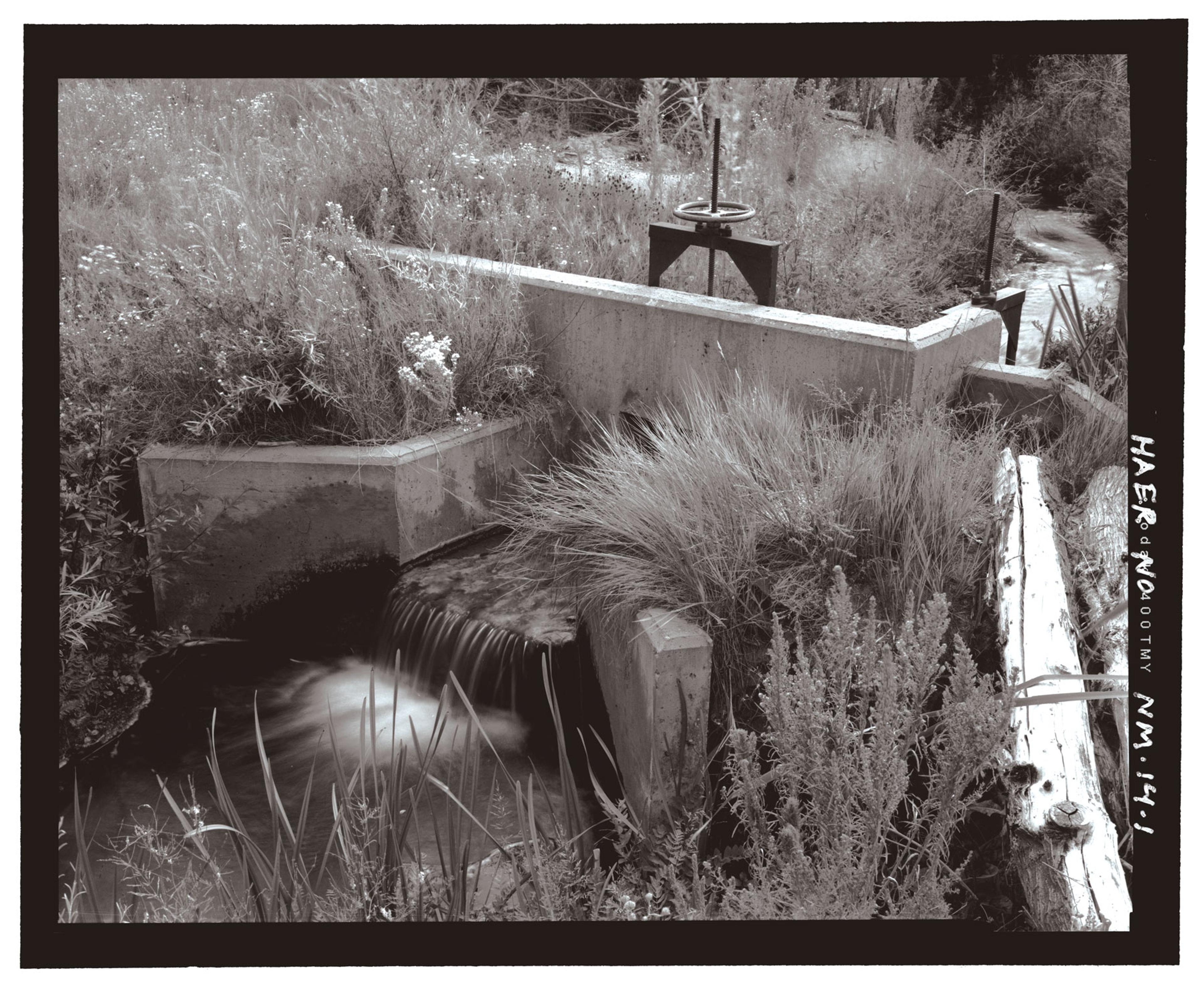

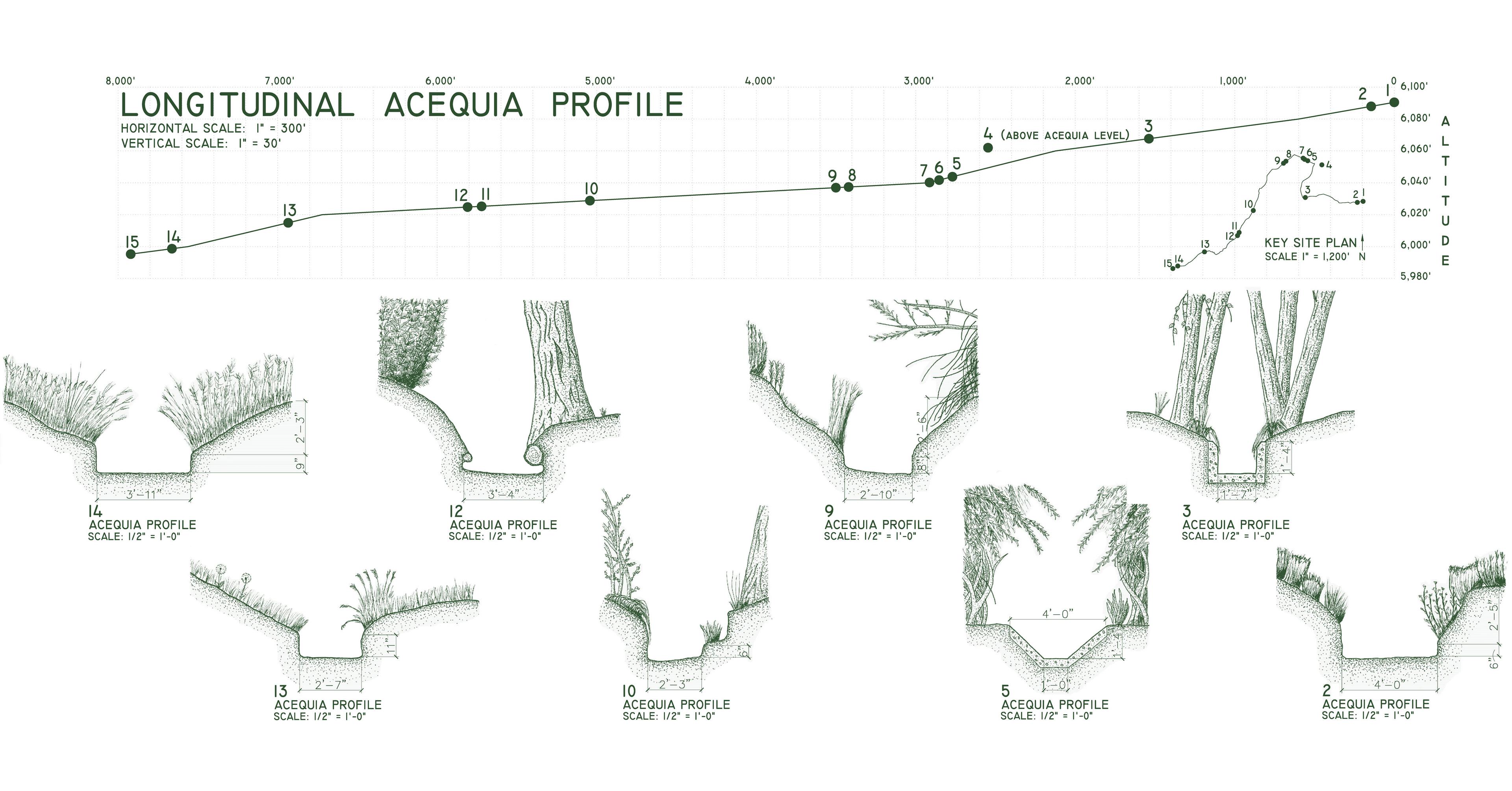

Acequia Profiles

·Diagram from Library of Congress

What might some of those other valuable outcomes be? Some recent research by acequia scholar Devon Peña suggests that acequias not only cut through desert landscapes; they reshape them. His ecological studies have illustrated how acequia architecture, which relies on earthen ditches, allows some amount of diverted water to seep into surrounding ecosystems, expanding the riverine footprint to

provide more habitat for native species, and over time, transforming soils, plant life, and even helping raise groundwater tables, all without the use of carbon-based energy. Perhaps it will not be a great leap for new studies to find that, with more water in the landscape, acequias also help arrest the advance of climate-related impacts like aridification.

In this way, acequias literally expand the livable space, not just for humans, but for animals and plants too. Left to its own devices, the Rio Grande would race unrelentingly through the dry mountains of northern New Mexico, acting as an effective drain. Acequias arrest that rush, sending parts of the busy river off its course for a few miles at a time, allowing water to infiltrate the soil, helping create homes for aspens and roses, muskrat and crawfish, Rick Martinez and Don Bustos, and thousands of other New Mexican farmers. These intertwining threads of water have bound these communities together for hundreds of years, creating an ecosystem strong enough to resist desolation even in the very heart of the desert.

This article first appeared in Ambrook Research Journal V. 01, a limited-edition print publication.