Investors are looking to boost fertilizer production by mining off the Namibian coast. Ocean advocates would like a word.

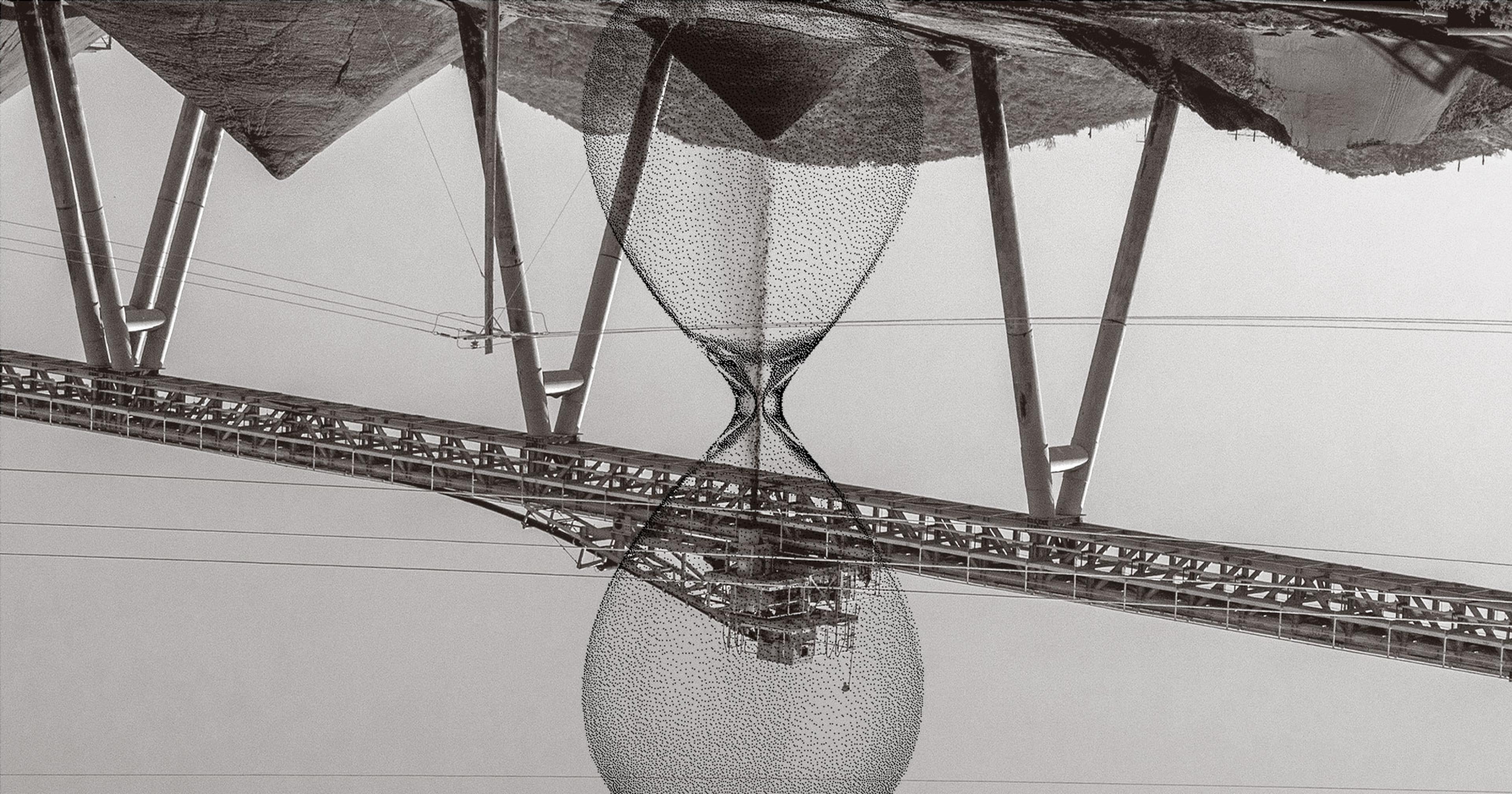

After plankton live long and productive lives in coastal seas, they slowly fall to the seafloor. With enough time — and plankton — they form a rock deposit of phosphate. When that phosphate is mined, it provides a critical ingredient for fertilizers around the world. Half of the world’s food comes from those synthetic fertilizers, and half of its phosphorus comes from those plankton.

Yet every single phosphate mine across the planet is on land. If it’s just waiting on the ocean floor, why wait until tectonics brings it above the water?

In Namibia, a proposal now sits on a commissioner’s desk for the world’s first marine phosphate mine, called the Sandpiper Project. It would mechanically dredge the sand below the coastal sea to extract the mineral. In the process, global farmers would get access to a little more fertilizer, and the company behind the project, Namibian Marine Phosphate (NMP), could make a tidy profit in a perpetually growing $27 billion industry.

The problem is that the offshore coastal shelves with the strongest upwellings and purest phosphate, including Namibia’s, are also home to a massive ecosystem of fish and fishermen. Sardines, mackerel, monkfish, and hake all live in the Benguela Current, off the coast of southwestern Africa, sustaining a Namibian fishing industry of 16,000 workers, That’s the third-largest industry in the country. But mining (primarily for diamonds and uranium at the moment) is Namibia’s largest.

Can you open a mine there without destroying the fishery? That’s the question in front of Namibia’s environmental commissioner, Timoteus Mufeti. In January he told me, “We expect the decision on this application to be made soon.”

The Sandpiper Project received a mining license in 2011 but was halted within a year due to environmental objections and a government moratorium on seabed mining forced. An Environmental Clearance Certificate issued in 2016 was overturned by Namibia’s High Court in 2021, and the project has remained inactive since, awaiting one more decision by the Environmental Commissioner. The health of one of Earth’s most productive coastal ecosystems could hang in the balance.

Global Growth

Mineral fertilizers mostly need three ingredients, Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Potassium (K). While plants use about 13 other elements, these big three are the most critical to plant growth and crop yield. Nitrogen comes from the air using high-pressure chemistry invented just before World War II. Factories producing it can be built anywhere in the world, generally using natural gas (though water can work too).

Meanwhile potassium is mined from ancient inland seas that evaporated slowly, where repeated cycles of seawater brought dissolved salts over time. These concentrated as seas evaporated, creating deep reserves. They’re rare, but pretty evenly distributed around the world. Canada produces the most, but Russia, China, Germany, and other countries have large deposits.

Phosphorus is different. Mined from biological material, there are only a couple of rich deposits in the world. Morocco holds about 70% of the global reserves, much of which is in territory called Western Sahara that the United Nations considers occupied. Its prices swing more wildly than the other two minerals.

Growth in demand for phosphate is estimated between 3-5% annually.

When they swing, those prices can shape the global food supply. In 2008, the price of phosphate rock doubled, which contributed to sharply rising food prices, hitting developing countries particularly hard. With world populations projected to hit 9 billion by 2050 and an estimated 70% more food needed, demand for the mineral isn’t going anywhere. Growth in demand for phosphate is estimated between 3-5% annually.

That has led some scientists to worry about “peak phosphorus,” where we’ll run out of the valuable mineral. But widely cited studies show we have at least 350 years worth of supply in reserve. Pedro Sanchez, director of the Agriculture and Food Security Center at the Earth Institute, does not believe there is a phosphorus shortage. “In my long 50-year career,“ he said, “once every decade, people say we are going to run out of phosphorus. Each time this is disproven.”

However, just like in oil, the easiest deposits are exhausted first, so companies have to begin extracting more and more challenging reserves over time. Namibian Marine Phosphate is the first to dip its toes into a new type of mine.

A recent Trump executive order declared “the threat of reduced or ceased production” of phosphorus “gravely endangers national security and defense.”

Phosphate provides such a boost to crop yields that some historians believe when the British built industrial mills to convert animal (and human) bones into a phosphorus-rich powder, it enabled them to outcompete their European rivals. A recent Trump executive order declared “the threat of reduced or ceased production” of phosphorus “gravely endangers national security and defense, which includes food-supply security.”

That security comes with costs, however. Because less than 20% of phosphorus applied in agriculture is uptaken by plants, the remainder runs off and can cause big environmental challenges like algal blooms and compromised water supplies. Many industry observers say that more phosphate must be recycled rather than relying on new stocks, which would also reduce the environmental damage. Still, demand for the mineral grows every year.

The world’s phosphate mines today produce about 240 million tons annually, which Sandpiper’s proposed 3 million tons wouldn’t tip the scales on. However, since it would be the first marine operation to scale, it could unlock a new category of extraction to be replicated elsewhere. Large volumes of phosphate are expected on the world’s continental shelves, but actual estimates globally don’t yet exist. Peru, Baja California, Morocco, and parts of Australia all have powerful upwelling habitats and recorded phosphorite deposits, but no one knows just how large.

Testing the Waters

“The Namibian fishery is already in a delicate state,“ Faye Brinkman, PhD in Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, told me. ”Many of Namibia’s most important commercial species depend on the continental shelf as critical spawning and nursery habitat, which overlaps directly with the depth range proposed for marine phosphate mining. These stocks have been shaped by decades of fishing pressure and are now further stressed by climate variability and long-term ecosystem change. Sardines have not recovered despite a fishing moratorium, suggesting the system is operating close to ecological limits.“

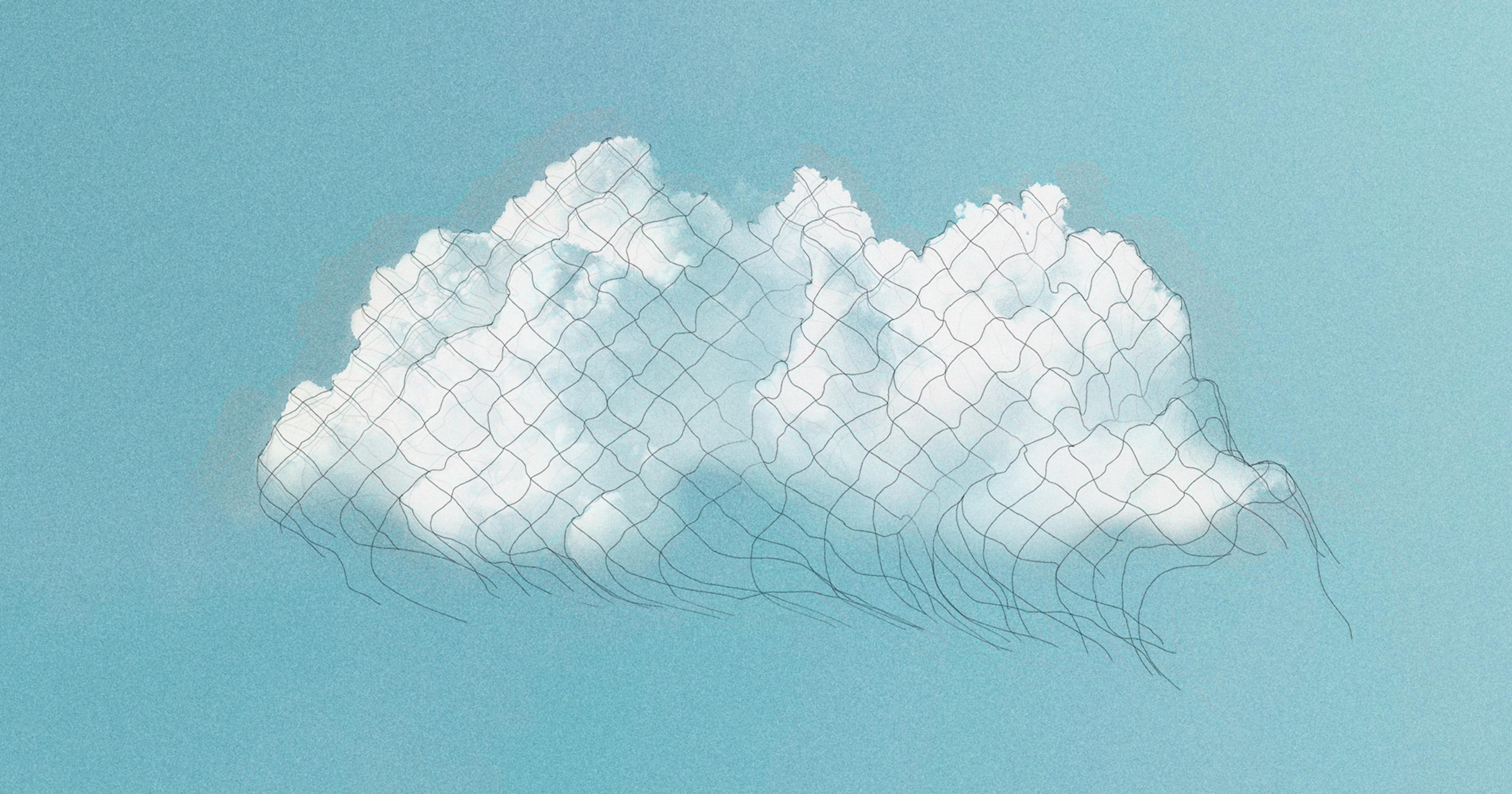

“Large-scale seabed mining in such a productive and sensitive area risks permanent habitat degradation, increased turbidity, oxygen depletion, and the release of toxic substances, all of which directly undermine fish recruitment and food-web stability. In a system that underpins livelihoods, food security, and national revenue, a precautionary approach is essential.”

For these reasons, the Confederation of Namibian Fishery Associations has noted its strong opposition to the project.

According to a recent interview with Paulus Kainge, ecosystem coordinator for the Benguela Current Convention (an international collective devoted to the health of this part of the African coast), “Fishing also contributes to food security, where per capita fish consumption in Namibia stands at about 13 kg. It is estimated that about 18% of the animal protein intake of the Namibian population is derived from fish and fish products.”

“The productivity of the fish stocks, and that of the entire ecosystem, will be negatively affected as the targeted mining area is not only the main spawning ground for important fish stocks like hake, but it is also a main nursery and recruitment area. So, this will result in significant species-level changes or impacts, such as extinction or significant decline in abundances.”

“Large-scale seabed mining in such a productive and sensitive area risks permanent habitat degradation, increased turbidity, oxygen depletion, and the release of toxic substances.“

NMP and supportive industry groups counter that extensive Environmental and Social Impact Assessments (ESIAs) have been conducted. Reportedly 28 studies with external peer reviews have indicated that the operation is unlikely to cause significant environmental harm or devastate fisheries. They cite historical coexistence between commercial fishing and other seabed activities, such as diamond mining, as evidence that regulated resource extraction and marine ecosystems can operate side-by-side.

Their 2022 Assessment says: “Commercial fisheries data indicate that the majority of historical fishing effort occurs outside the core mining area. No population-level effects on commercially important fish species are predicted as a result of the proposed dredging activities.”

NMP is majority owned by Oman-based Mawarid Mining, and most of its board is comprised of oil and diamond mining executives from other countries. One of the board members, Chris Jordinson, was convicted of insider trading in his home of Australia. It’s possible they are less familiar with the vulnerability of the environment off the coast of Namibia than in their home countries.

However, even if marine mining for minerals like diamonds wasn’t extremely damaging (and it is), phosphate mining offers new challenges that could wreak havoc. While diamond deposits are concentrated in a few patchy layers, phosphate is diffusely spread through huge areas that require dredging almost all of the ocean floor (and nesting habitat) of the target region. At the same time, marine mining is likely to spill sediment, phosphate, and pollutants into upper layers of the ocean, causing hefty damage. All in the most environmentally sensitive area of the coast, where the fishing industry depends on strong populations.

Fish or Farms?

The debate and coming decision on Sandpiper reflects a global tension between two essential dimensions of food security. Without abundant phosphate, global farmers would not be able to grow at their current scale. Simultaneously, fisheries produce almost 100 million tons of food annually, which can be more than 50% of animal protein consumed in developing countries. Extracting marine phosphate could boost farm production while limiting access to critical fish.This tension plays out most starkly in countries like Namibia, where both sectors are central to economic sustainability.

Other powerful coastal upwelling ecosystems, likely to have potent phosphate reserves, are off the coast of Peru, California, Pakistan, and Vietnam. If Sandpiper succeeds and demonstrates strong profits, they could all be on the table.

For Sandpiper itself, its phosphate would be exported away from Namibia. Its few million tons won’t upend the market on its own, but if enough other marine mines emerge, fertilizer prices could eventually stabilize or even drop. That would support farms globally. But long-term ecological risks would be localized, affecting fisheries, protein supply, and food webs that are already under pressure. The hunger that it reduces globally might be dwarfed by what it causes locally.