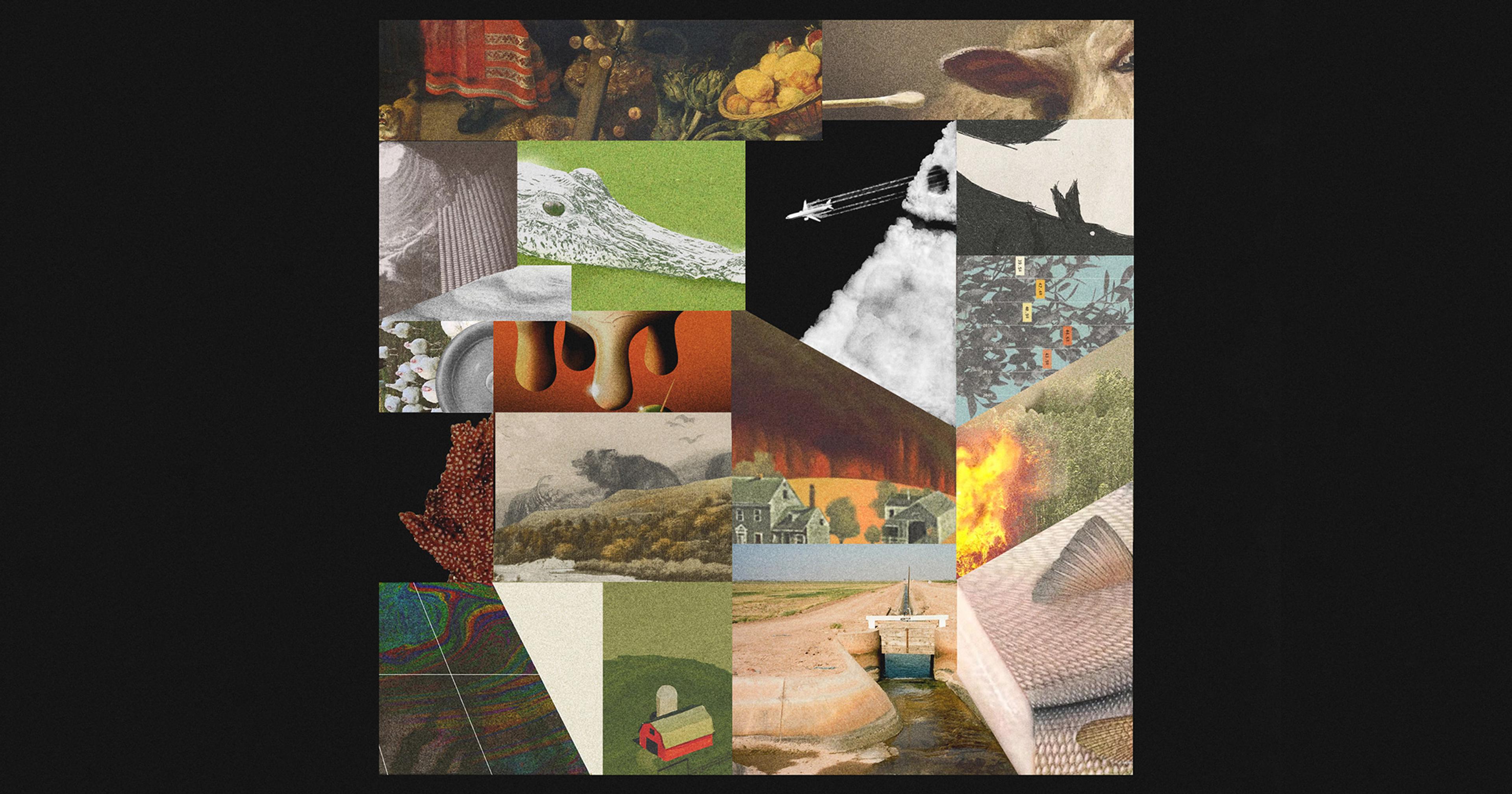

Dan Egan’s latest book investigates how phosphorus fertilizer enables the world’s food system — exacting a great price from from all of us.

Out of all the elements on the periodic table, phosphorus could have the most checkered — gothic, even — past. Phosphorus mostly does not appear in a pure form in nature. Yet it is a remarkable catalyst for plant growth, and has long been tapped into as fertilizer. To extract it, humans have performed a variety of unsavory tasks, many entailing Faustian bargains. In 1815, after the Battle of Waterloo left tens of thousands of corpses behind on the lowlands of western Europe, reports emerged of disturbances to the dead. Grave-robbers dug the bodies up and sent them to England, where their bones were in demand as — in a salient twist — fertilizer.

Although the English had previously used animal bones and manure for phosphorus, they needed more, and they found it in human corpses. Mills pulverized the bones into powder, then sent it to be scattered on fields. This grisly supply chain led to unprecedented crop growth, fueling England’s rise as an industrial and colonial power in the 19th century. In The Devil’s Element: Phosphorus and a World Out of Balance, Dan Egan presents readers with this history before laying out the massive impact phosphorus had over the following centuries.

An environmental journalist, Egan visits communities from the American Midwest to northern Germany that have deep ties with phosphorus fertilizer — the production of which has moved from bones and manure to extractive phosphate mining. His interviewees detail how fertilizer overuse and runoff have impacted the world and its people. They vividly narrate mysterious ailments and waterways that have turned a ghastly green.

Egan writes, “Phosphorus is the elemental link that completes the circle of life.” Written for a general audience, his book is full of lively anecdotes that propel new understandings of the world’s food system. He juggles explication with a keen sense of the bigger, heavier questions that surround phosphorus use.

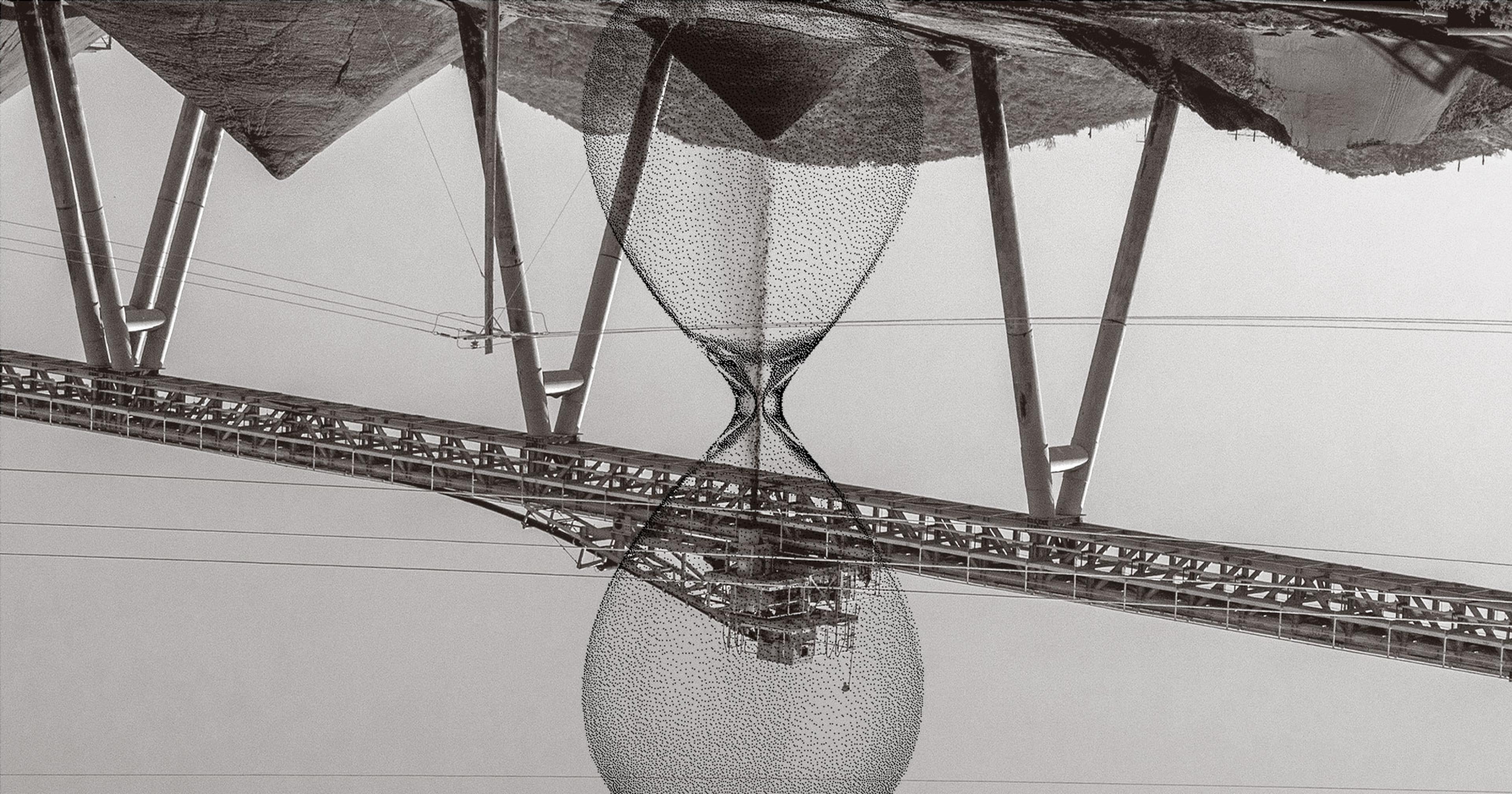

Phosphorus follows the law of conservation of energy: Indestructible, it persists by shifting from one form to the next. Historically extracted from bodily waste and remains, it never loses its potency, activating a perpetual cycle of pollution. This element is volatile. It can as easily stimulate growth as cause profound destruction. Egan notes how some have weaponized this destructive quality in the form of phosphorus bombs, whether in Germany or Ukraine. More recently, Israel used white phosphorus against Gaza and Lebanon. Egan writes, “Whether in water, on land, or toggling between the two, the phosphorus atoms let loose in the world entered a timeless tick-tock between the living and the lifeless.”

For newcomers, Egan’s evocative framing creates a context for the large body of phosphorus research being produced today. A 2023 Idaho study traced the impact of glyphosate, a phosphorus-containing pesticide that has elsewhere been used in chemical warfare, on 40 pregnant women. Phosphorus exposure caused shorter gestational lengths and reduced fetal growth. Consuming an organic, glyphosate-free diet for one week did not make any difference to their exposure.

“If you live close to a field during the spray season, you’re getting so much of your exposure from that residential proximity that your diet is a drop in the bucket,” said Cynthia Curl, one of the scholars driving the study. After reading Egan’s assessment of how phosphorus mediates the cycle of life and death, it is difficult not to see it animating the data.

When phosphorus spills into water bodies, it continues to catalyze exponential growth. In particular, it fertilizes blooms of cyanobacteria, a distinctly green algae that chokes aquatic life and makes water unsafe for drinking or swimming. Egan documents how algal blooms have created dead zones from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. Since it spreads across watersheds, cyanobacteria makes a surprisingly effective narrative device. A Wisconsin resident, Egan writes movingly about how cyanobacteria has infiltrated the waterways of his youth. He speaks to farmers and other locals with similar laments.

“The phosphorus atoms let loose in the world entered a timeless tick-tock between the living and the lifeless.”

“It is undeniable that we have cracked the circle of life and turned it into a straight line, and that line has an end,” Egan writes. Despite the labored metaphor — it’s hard to square a line with the shape-shifting character of phosphorus — the stakes are clear. At times he gets lost in glibness. His brief accounts of environmental racism leave a good amount to be desired and showcase the limits of Egan’s scholarship. But when he dives deeply into a place or story, he does manage to bring readers to unfamiliar terrain while illuminating sometimes stupefying relationships.

Donald Boesch, a marine science professor at the University of Maryland, said, “As a scientist, you’d like to see details. But I think [the book] does a very effective job of telling an interesting story and bringing people into it.” Phosphorus research reveals plenty of startling arcs.

Boesch has spent his career studying the Chesapeake Bay, which suffers acutely from legacy phosphorus. “We actually see, despite the efforts, some recent trends where runoff of phosphorus is increasing,” he said. Boesch said fertilizer has accumulated so much in regional soil that reducing use does not necessarily result in decreased runoff.

The gap between research and policy motivates this book. Egan talks about how farmers can voluntarily reduce fertilizer consumption but that the environmental impacts don’t provide sufficient incentive. “Voluntary has not worked yet,” said Donald Scavia, a professor emeritus of environment and sustainability at the University of Michigan who formerly served in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “It needs to be something more than voluntary.”

Boesch suggested that the money for incentives exists, but ought to be redirected. “Different federal policies … provide lots of money to pay farmers to farm more effectively and efficiently. That’s the power of that money and how we use it could be enormously influential,“ he said.

Solutions are certainly easier to come up with than to implement.

Solutions are certainly easier to come up with than to implement. In the last section of his book, Egan advocates for better wastewater treatment of human excrement for use as fertilizer, delighting in the shock value of a solution that doesn’t align with typical conceptions of hygiene. Yet the most sizable phosphorus polluter remains animal waste. Although it is far from easy to condense the past, present, and future of the element into a short read, there could have been a more balanced analysis of solutions.

Scavia emphasized the importance of outcomes in developing solutions. “It’s hard to measure phosphorus coming off of an individual farm, but you can monitor it in the larger watershed. One of the ideas is you bring all that group of farmers together, and you tell them, ‘If you reduce the nitrogen and phosphorus coming off the watershed, you will get aid,’” he said. Farmers don’t need to be told how to reduce nutrient runoff, just rewarded for achieving results.

When alchemists synthesized pure phosphorus in the 17th century, they knew that they were playing with fire. After his defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon was exiled to the British possession of St. Helena. He went from globe-spanning ambition to confinement on an island used for guano mining — a symbolic emblem of the hubris swirling around the tale of phosphorus. One of Egan’s choicest quotes comes from the German chemist Justus von Liebig. Of England’s phosphorus extraction, Liebig said, “Like a vampire it hangs upon the breast of Europe, and even the world, sucking its life-blood without any real necessity or permanent gain for itself.”

Now, we must grapple with the fallout at a scale stretching beyond the scope of U.S. foreign and domestic policy. At the end of the day, the profile of phosphorus is very human. It tells of greed and nutrition, industry and depravity. Its attraction lies in its reward and its risk. As Egan shows, this leaves us sitting uncomfortably with our own responsibility.