Massive federal action stopped the Dust Bowl in its tracks. Will policy changes erode the progress we’ve made?

Ninety years ago in 1935, a cataclysmic wall of dust swept across the Great Plains. Known as Black Sunday, it wasn’t the beginning of the Dust Bowl era, but it was the moment it entered the public consciousness. Photographs of towering clouds swallowing towns stunned Americans, driving home what had already been years of creeping environmental catastrophe.

The Dust Bowl began in the early 1930s, as drought gripped the central United States. Unsustainable agricultural practices, particularly intensive tillage of fragile prairie soils that they thought would enhance its moisture retention, had caused massive erosion. Soaring commodity prices in the 1920s and new tractor technologies had caused farmers to expand operations to produce huge volumes on marginal land. As the drought deepened and topsoil blew away, millions of those acres became unproductive for decades. Entire communities were displaced, and the federal government responded with landmark legislation that changed United States agriculture for most of the last century.

Now, those protections could crumble under changing federal priorities.

Today, conservation practices have grown considerably, largely thanks to federal policies. Cover crops grow on at least 5% of total U.S. cropland (around 15 million acres). Acreage cultivated without any tillage is over 100 million acres, and the USDA estimates that reduced tillage now comprises the majority of cultivated cropland.

Still, the gulf between health and declining soils in U.S. farmland is deepening. Dust storms affecting roadways in 2025 killed eight people in Kansas and four in the Texas Panhandle. Climate change is making these cataclysmic events even more likely. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, “Although erosion rates have slowed since the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) began estimating them in the 1980s, soil loss from the nation’s farms is still unsustainable. Every year, U.S. croplands lose at least twice as much soil to erosion as the Great Plains are estimated to have lost annually during the peak of the Dust Bowl.”

Without the right mix of federal policies, incentives, and networks, the progress that’s been made over the last 90 years could erode. The gains of the post-Dust Bowl era were the result of deliberate, layered investments including locally led conservation districts, federal technical assistance, and a broader shift in agricultural norms. The National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) today is facing structural changes that could affect them all.

The First Response

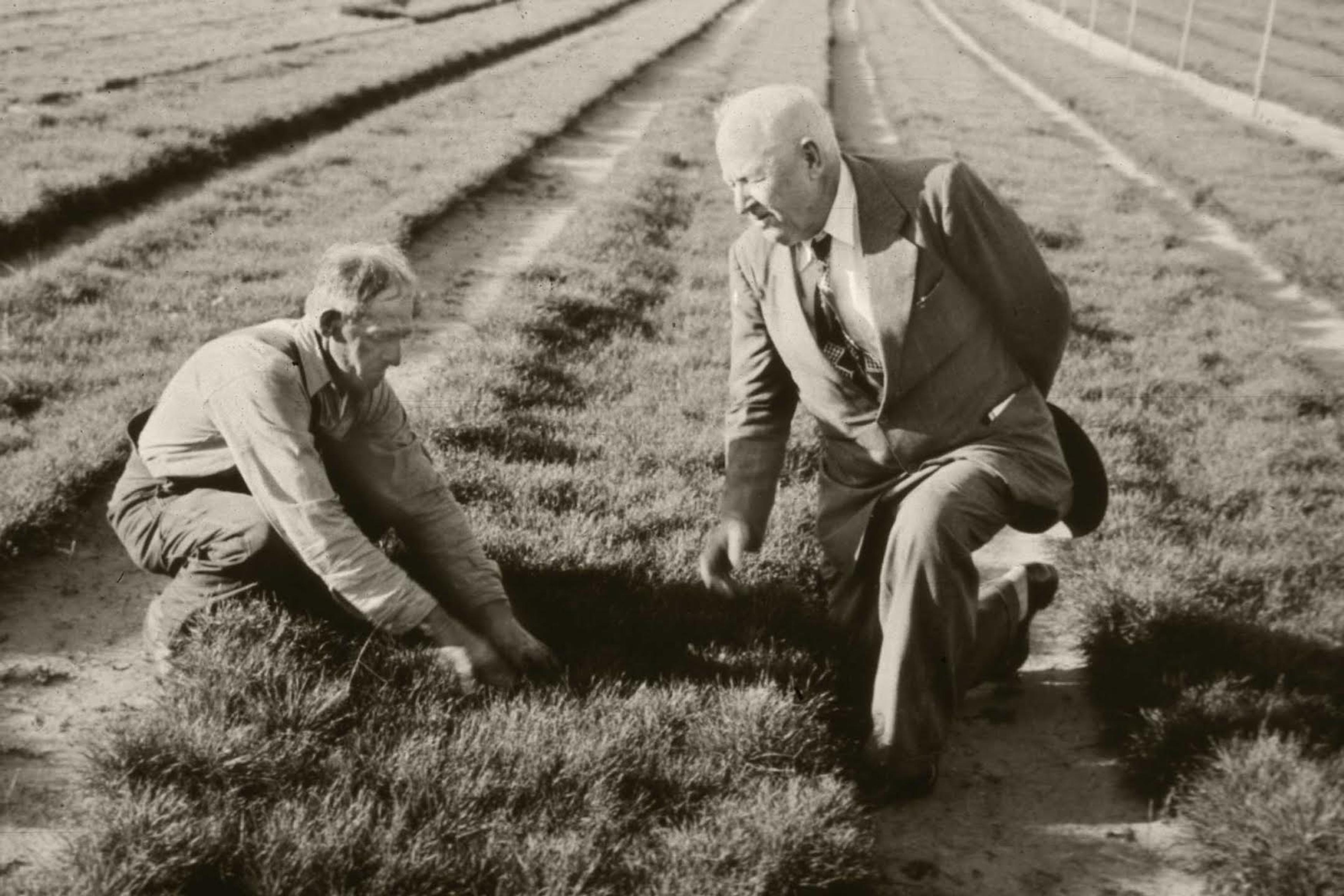

The Soil Conservation Service (SCS) was formed in 1935 following dramatic congressional testimony from Hugh Hammond Bennett, calling for a federal response to the soil erosion crisis on the exact day that the dust from Black Sunday blanketed the sky above the U.S. Capitol.

Promptly, the Roosevelt administration formed the Soil Conservation Service and appointed Bennett head; this agency ultimately became the NRCS in the 1990s. This group provided direct cash payments per acre for conservation techniques, such as planting soil-conserving crops, contour plowing, cover cropping, and retiring highly erodible land.

Hugh Hammond Bennet, right, the first head of the Soil Conservation Service, speaks with a farmer in his field.

One lesser-known element of the Dust Bowl policy response, beyond financial incentives and crop insurance programs, was the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act’s creation of conservation districts throughout the country. These locally led entities were rooted in peer-to-peer networks: farmers working with fellow farmers, supported by federal technicians. Demonstration plots on private land were dotted across the country, showcasing sustainable practices, serving as powerful tools of persuasion. A culture of conservation began to take hold, reinforced by neighbor-to-neighbor engagement. Today there are over 3000 conservation districts in the United States.

This layered approach, leveraging financial incentives from above and social cohesion from within, formed a durable model for promoting sustainable agriculture. Work wasn’t perfect, but it was advancing. For decades, SCDs served as hubs of innovation, advocacy, and practical support.

The Rise of Top-Down Incentives

Direct payments, through Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) payments, Environmental Quality Improvement Program (EQIP), Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) have grown from the 1940s to the 2000s alongside crop insurance subsidies, forming a suite of financial tools to encourage environmental stewardship.

However, recent research suggests these top-down financial incentives alone face huge challenges. Aparna Howlader, professor of economics from Chatham University, analyzed every conservation district and demonstration plot in the decades following the Dust Bowl and found that while financial incentives for conservation practices were available nationwide, “empirical data analysis shows that areas with strong conservation districts had a consistently higher yield and profitability during the massive 1957 drought.”

According to Howlader, “Soil conservation strategies mostly work when neighboring farmers are working together.” In times of high commodity prices, the appeal of conservation payments weakens. Land that might otherwise be left fallow or cover cropped is instead kept in production. Additionally, tenant farmers, who often make land-use decisions but don’t receive direct payments through federal programs, may lack motivation to adopt conservation practices at all. Soil conservation districts and their networks of technical support appear to have offered a kind of insulation against the boom-bust dynamics of commodity agriculture.

Today’s Soil Policy Environment: Incentives Retained, Support Eroded

Funds for federal conservation incentives programs are stable now, but other policy shifts may be undermining their effectiveness. The GOP-backed One Big Beautiful Bill maintains EQIP, CRP, and CSP funds by rerouting funds earmarked for climate resilience from the Inflation Reduction Act. Simultaneously, technical support around those practice changes is dwindling.

According to Richa Patel, policy analyst for the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, “The greatest challenge for soil health today is wavering federal support.” The White House has proposed eliminating the NRCS’s entire Conservation Technical Assistance (CTA) division, which now awaits congressional approval. Patel said, “CTA is a foundational component of supporting farmers in adopting conservation practices — and ultimately improving soil health and productivity — on their farm.”

This is in addition to the Department of Government Efficiency terminating the leases of 59 office leases for the Farm Service Agency/NRCS and approximately 12,000 NRCS staff dismissed in mass firings. Funding freezes at the beginning of the new administration either paused or ended tens of millions in support for conservation districts. The federal architecture of conservation is tilting heavily towards financial incentives as the scaffolding of peer networks and technical is eroding.

Conservation districts themselves and the technical support they represent are experiencing uneven funding shifts. In some states, like Texas, Minnesota, and Oregon, resources have kept generally stable or even increased. More, like those in Illinois, Indiana, and Arkansas have sharply reduced funding due to state or federal policy shifts. Others, like California, have funding in limbo from federal changes to the Inflation Reduction Act.

The National Association of Conservation Districts represents the nation’s conservation districts to Congress. According to their CEO, Jeremy Peters, “One of the things we’re concerned with is a generational loss of conservationists. If the resources for technical support aren’t available, then we may lose the opportunity with this next generation of farmers to demonstrate how important conservation agriculture is to their bottom line. Our research shows on average, farmers can realize a net increased return of $65 per acre, based on efficiencies that are gained through conservation measures.”

At the same time, today’s crop insurance programs provide little incentive for new conservation techniques, as the risk for lost harvests from soil erosion and climate change for large farms falls on the federal government rather than the farmers themselves.

The Farm Journal’s 2020 “State of Sustainable Ag” report surveyed 500 farmers and found more than half believe implementing conservation practices typically improves a farming operation’s profitability in the long run. “Row crop farmers tell us they are willing to do the work, but they do not feel that they can, or should, individually shoulder the burden of the agronomic and financial risk associated with adopting new practices.”

Targeted soil conservation incentives are just one piece of the puzzle, however. Patel said, “To help prevent future Dust Bowl-like conditions, not only are voluntary programs like CSP valuable for increasing the implementation of important soil health practices, but it’s important we don’t continue to subsidize unsustainable farming practices on lands that are unsuitable for farming. Ideally, basic soil health standards tailored to all farmland can become a future prerequisite to receive federal crop insurance and commodity subsidies.”

Looking Back, Looking Forward

The Dust Bowl catalyzed an extraordinary response of federal investment, local engagement, and cultural transformation. In the decades that followed, resilient networks took hold, centered around conservation districts to embed a conservation ethic into rural life. Today, that ethic persists, but the structures that supported it are under strain.

Ninety years on, the lessons of the Dust Bowl remain visible in the programs and policies that shape American agriculture. Financial incentives from the federal government remain strong, but the support structure around them to help the transition towards conservation practices are faltering. Future policies, and farmers’ decisions in their fields, will determine whether 90 years of response after the Dust Bowl is taking root or in the wind.