Because of its resilience and drought-resistant properties, some have suggested hemp as a replacement crop for cotton. We’re not there yet.

During this past summer of intense heat, drying winds, and drought, the cotton farmers of northwestern Texas took an estimated $2 billion beating. Plants that should have matured into fluffy seed cotton balls withered. Those that did manage to bloom grew to a quarter or a third of their normal size, causing some farmers to simply leave them on the fields, forgoing the expense of a weak harvest. The result: a 58% drop in production for the state that grows almost half the cotton in the U.S., according to Phys.org, and possibly the worst cotton-growing year there in three decades.

Another crop, hemp, has been touted as potentially more drought resistant than cotton, leading to speculation by hemp enthusiasts that it could replace the world’s most widely used natural fiber. The versatile crop has shown promise in boosting the sustainability of textiles by replacing polyester fibers in blends, farming systems, even construction. (Meet the green building material called hempcrete.) If you imagined, though, that we’re nearing an era of hemp clothes everywhere — as touted by celebrities like Woody Harrelson and Emma Watson — we’re still a ways off.

It’s a crop that requires a license to grow, which is a hassle. Despite its versatility, there’s limited infrastructure to support fiber hemp and few markets into which to sell it, making many farmers wary of taking the risk. Even the rumor of hemp’s superior drought tolerance needs more research. “There’s a lot of work that still needs to be done in terms of understanding [hemp’s] resilience or drought susceptibility,” said David Suchoff, alternative crops extension specialist at North Carolina State University and director of the FFAR Hemp Research Consortium. He said that while fiber hemp crops survived a dry North Carolina June, in parts of Texas it got pummeled just like cotton this year.

Nevertheless, fiber hemp is beginning to show how it might have an important role to play in the future of sustainable materials. The trick: finding just the right cultivars for just the right and willing regional farmers, and building out the supply chain, bit by bit.

Seeding the Industry

Fiber hemp is grown exclusively for its stem so maximum plant height is desirable; the outer stem is gleaned for textiles while the core might become fuel or mulch or animal bedding. But domestic research into cultivars that do well in U.S. crop systems is lagging and, “We’re not at the point where we have a good domestic supply of seed,” said Suchoff. At the moment, most fiber hemp seed being used in the Southeast hails from China, the global leader in hemp production, which has been cultivating the crop for thousands of years. It’s cheaper and easier to procure seed from the EU, but these varieties flower too early in North Carolina or Texas, resulting in stems that are only two feet tall.

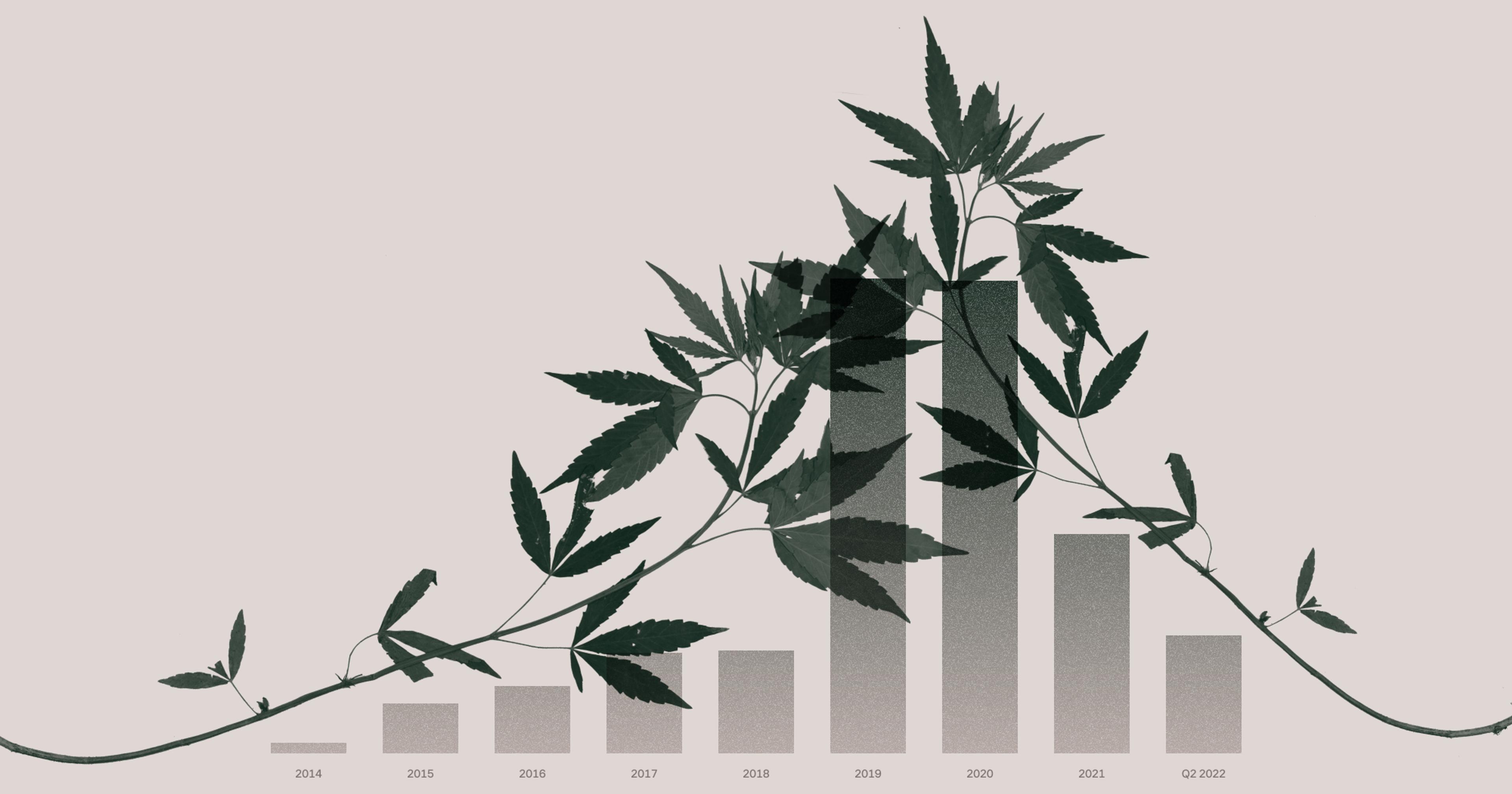

Some U.S. seed breeders are beginning to make headway on domestic production. But for the moment, the cost of imported seed, on top of its uneven performance, “inflates the input costs on the farmer to grow this crop,” Suchoff said, which makes it a hard sell. So does the fact that THC levels in Chinese seed “tend to be above the 0.3% levels that are [allowable] to meet federal guidelines here,” said Calvin Trostle, a professor and extension agronomist at Texas A&M AgriLife. Trostle is hoping the 2023 Farm Bill might expand the regulation from the 2018 bill that almost entirely addressed cannabinoid hemp meant for CBD production, an industry that bottomed out in 2020 — not the stuff grown for stalks and fabric. (Any crop with over 0.3% of THC has to be destroyed; “That should be moot for a fiber or grain crop,” said Trostle.)

Amping Environmental Benefits

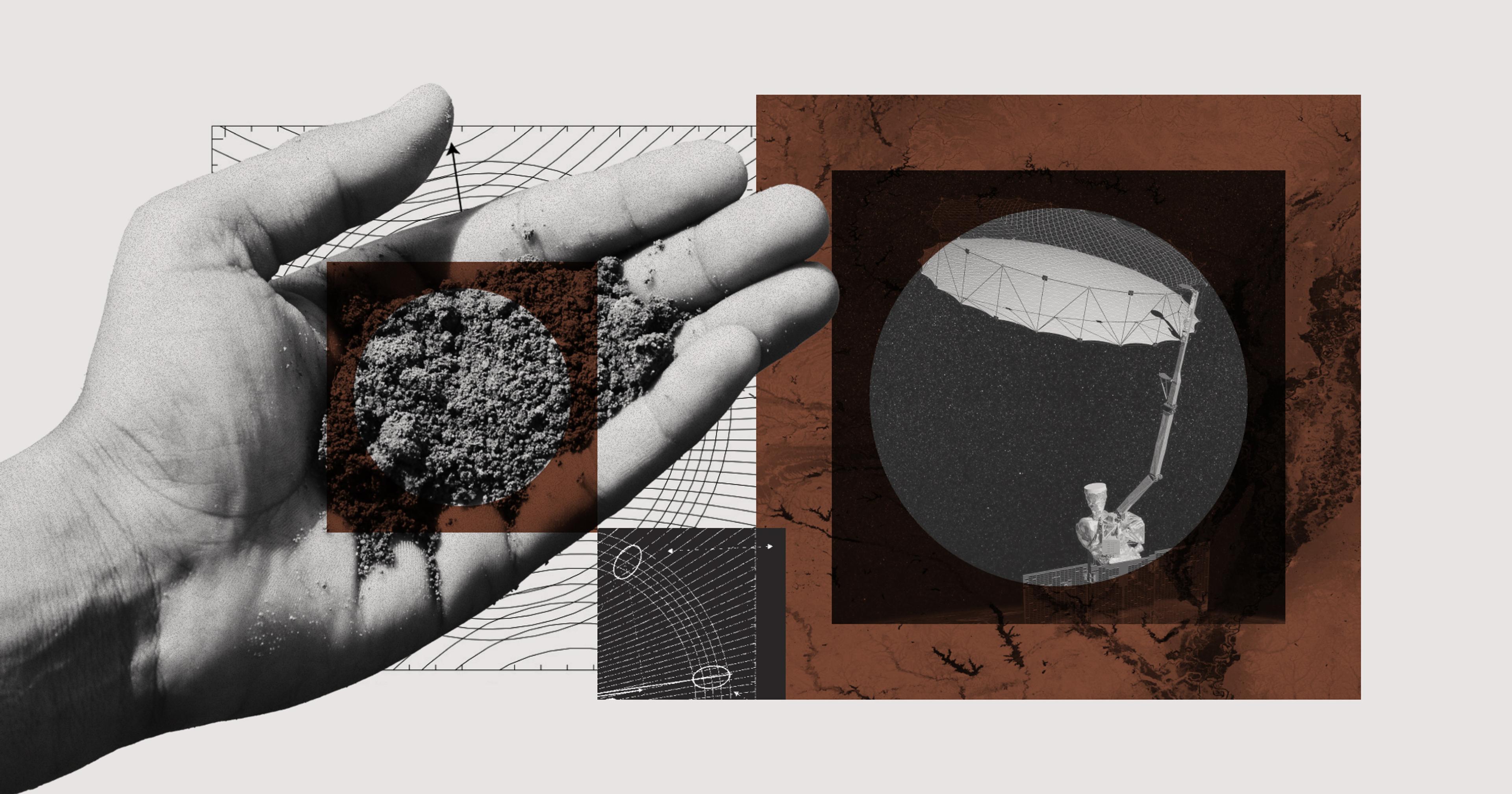

In Texas, North Carolina, Kentucky, and elsewhere, farmers are experimenting with plots of fiber hemp, trying to figure out its effects on soil health and other benefits. A lot of that depends on where the hemp is grown, “what variety you’re growing, the soil you’re in, when you’re harvesting it, and the type of system you’re producing — if it’s grain, if it’s fiber, if it’s dual crop,” said Suchoff. “There’s preliminary evidence showing that it does leave a pretty robust root system after harvest, and in rotation … folks will say that my wheat crop, my corn, my soy, did better after hemp.”

No one’s quite sure why, yet. When fiber hemp is harvested, its woody stalks are left to break down on the field so the bast fibers needed to make textiles are easier to separate from the stem’s woody core. “Those nutrients are going back into the soil, almost akin to how we manage cover crops,” Suchoff said. “The crop that is planted afterwards might be getting the benefit of the residual nutrients; the hemp root system may be able to tap into nutrients deeper in the soil, bringing them up closer to where more shallow rooted crops can utilize them; it could be improving the structure of the soil, allowing for better movement of water.”

Like all plants, hemp also pulls carbon out of the atmosphere and stores it in all its various parts and in the soil, potentially important for mitigating climate impacts. Unlike corn or soy but similar to trees that are harvested for their wood, long-lasting industrial hemp products — fiber or construction materials such as hempcrete — store carbon too, Trostle said.

On the downside, there are currently no herbicides that are labeled for fiber hemp use. But seeds can be planted very close together and they grow fast enough, in some instances, to out-compete weeds. Also, said Trostle, “There were some early beliefs that hemp was a more drought-tolerant crop than cotton and would use less water. But farmers in my region [of Texas] say that to get to the level of production that you need for fiber, you’re probably looking at 25% more water than what you would put on that piece of land if it was a cotton crop.” Trostle and others are currently researching this but he said in places that get plenty of rainfall (as opposed to arid places like Lubbock that rely heavily on irrigation), this shouldn’t matter.

The Processing Dilemma

Fiber hemp requires rigorous and highly specific processing methods, as described in the figure below.

| How fiber hemp is harvested and processed: |

|---|

| 1. At harvest, crop is cut and stems are retted, i.e., left to break down in the field for a few weeks to aid separation of the bast fibers — what’s used to make fiber — from the woody core of the stalks called the hurd (used to make products like hempcrete). |

| 2. Stems are crushed in mechanical rollers in a process called decortication. |

| 3. Bast fibers are de-gummed, with heat, pressure, or other methods, to remove lignin and hemicellulose. |

| 4. Remaining cellulosic fibers are spun into hemp fiber. |

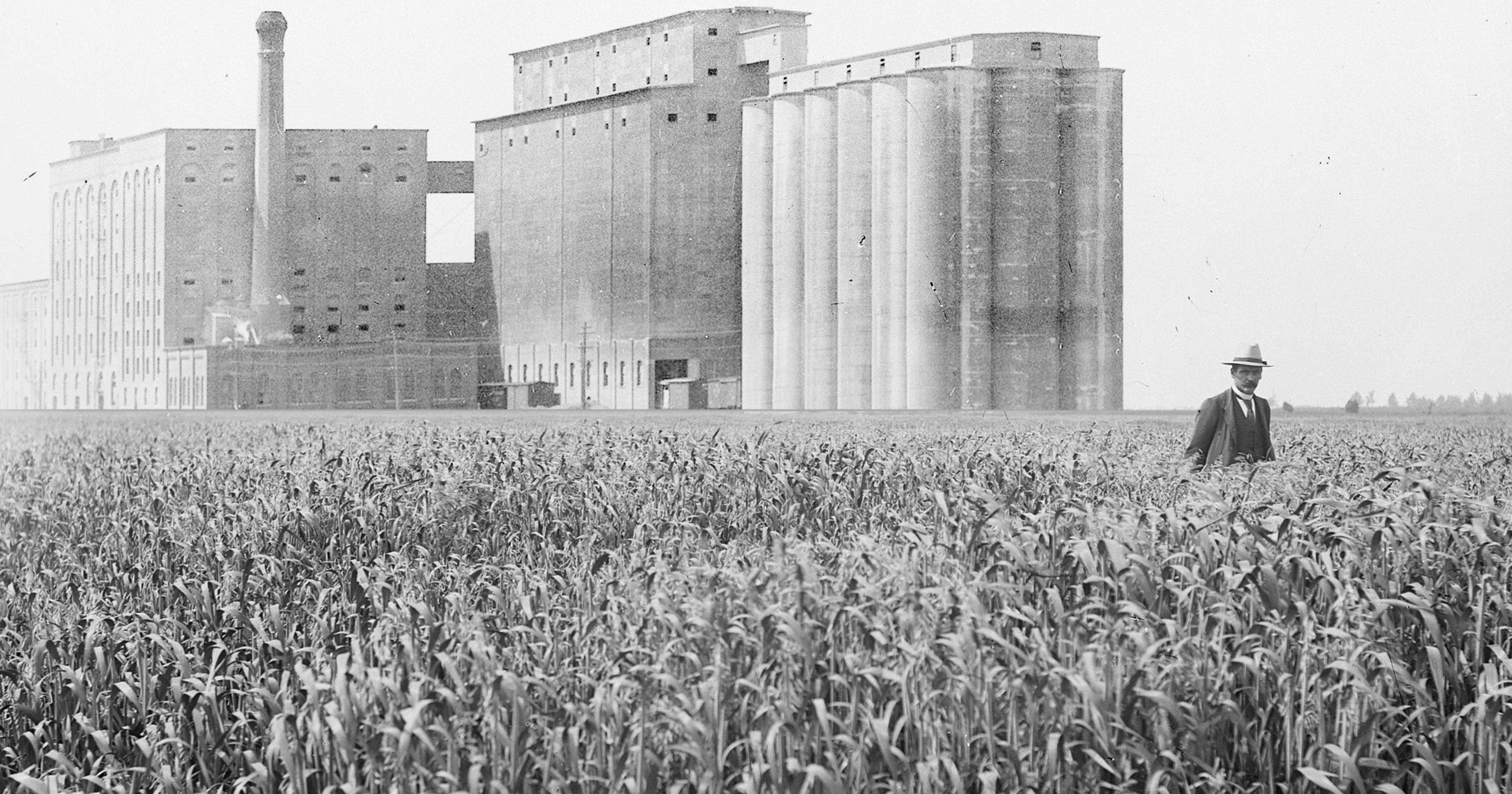

North Carolina has several facilities in place but elsewhere, the lack of that infrastructure is one of the biggest hurdles in getting farmers to plant it. Currently across the U.S., a little over 54,000 acres of farmland are planted with industrial hemp (versus almost 12 million acres for cotton). Bryan Wilson, co-founder of Environmental Living Industries, has spent the last few years scraping up $50 million to build a hemp processing plant in Dumas, Texas. Rather than starting from scratch, Wilson approached a Belgian manufacturer and made a deal to purchase $20 million of processing equipment from them.

It’s been complicated. “When you’re breaking ground on a new industry, going from zero to one is always the hardest part,” Wilson said. “But this is the same thing every other agricultural industry has had to go through whenever it starts industrialization.” When Wilson’s facility opens in late 2023, he said it will be able to process 12 tons of hemp fiber per hour; eventual capacity will be 80,000 tons per year. First, though, Wilson looped in two large-scale local farmers to grow 100 test-crop acres of an Australian strain of fiber hemp called MS-77 — it’s low in THC and proved high-yielding in Texas panhandle conditions. Wilson located harvesting equipment in Lithuania, “basically building out the entire supply chain all the way up to offtake,” he said. But the next challenge: “Who wants to buy this product from us right now, even before we get started building?”

Wilson said demand for industrial hemp products currently exceeds the processing potential of all U.S. facilities combined — what he calls a chicken-and-egg problem: “The industry is limited by the scale of processing, and processing is limited by those willing to risk establishing [off-taking] agreements with processors that are in their infancy.” Even when the industry does manage to scale up, Trostle, Suchoff, and Wilson don’t foresee a future for hemp-only garments — hemp, though durable, isn’t as soft as cotton. Said Trostle, “Even if things went really well, the scale of hemp fiber production would probably be only 1% or 2% of what Texas cotton acreage is.”

What experts do see for the future of the industry is “fiber hemp being a replacement for synthetic polyesters that they’re putting in cotton blends — that’s where I think that you’re going to see synergies between the two,” said Suchoff. Once infrastructure and markets are in place, he envisions farmers growing them both, possibly even in rotation, lending biodiversity to what would otherwise be a monoculture system for cotton farmers, and giving those farmers a second source of income. “I would love to see industries develop circular economies [that] flourish around this crop,” Suchoff said.