During a historically dry year for crops, the space agency is aiming to work more closely with the agricultural community.

When NASA Earth scientists recently visited the Flickner Innovation Farm in Moundridge, Kansas, as part of the agency’s new “Space for Ag” listening roadshow, visiting farmers were engaged and excited. Perhaps most thrilled were Ryan Flickner’s children, 8-year-old Owen and 5-year-old Miles, both wearing NASA logo-emblazoned t-shirts.

“They know NASA, but they didn’t know NASA knew anything about agriculture,” said Ryan, who is the sixth generation involved in the 850-acre Flickner Farm, working with his father Ray who grows corn, wheat, and soybeans.

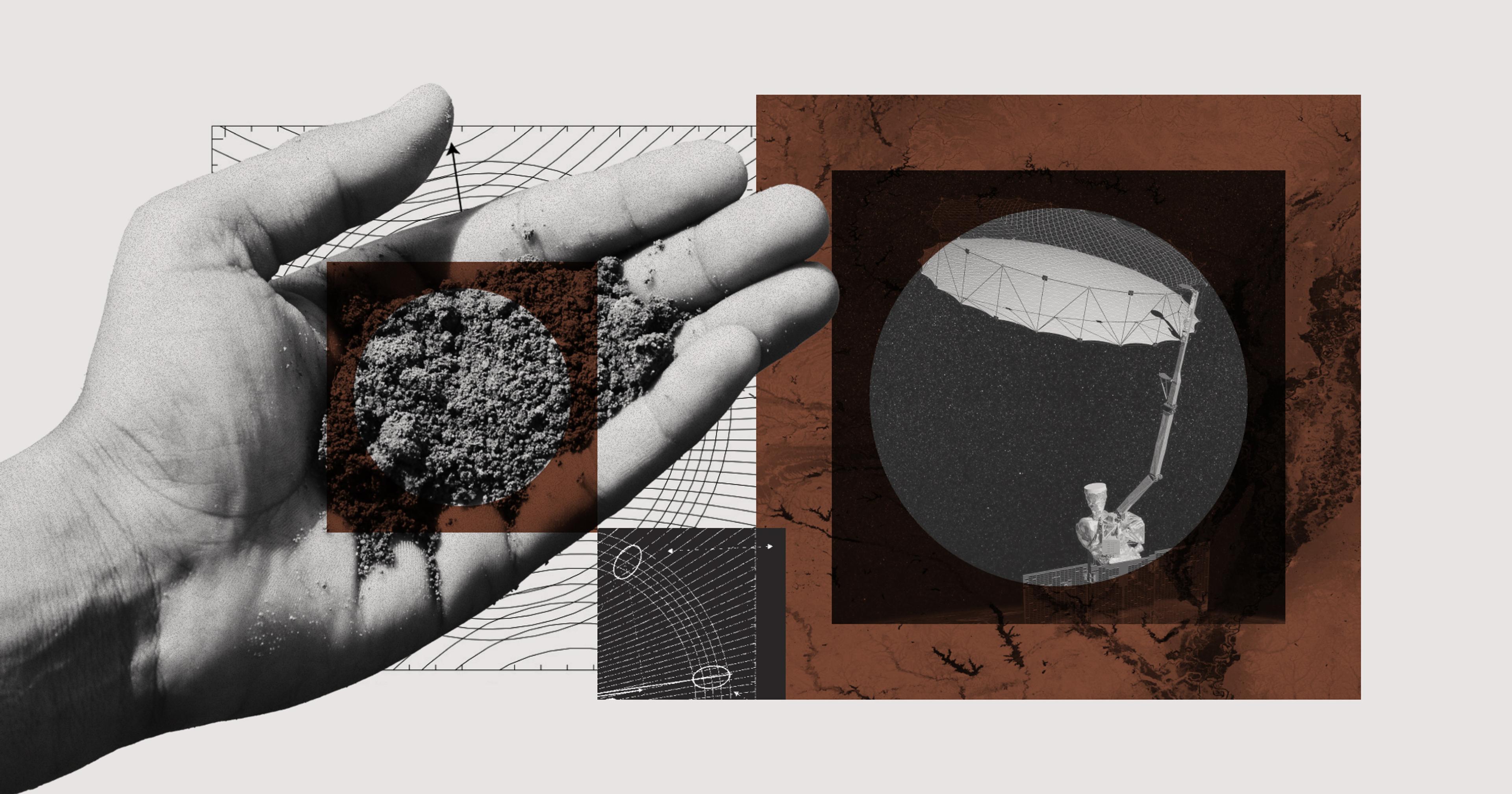

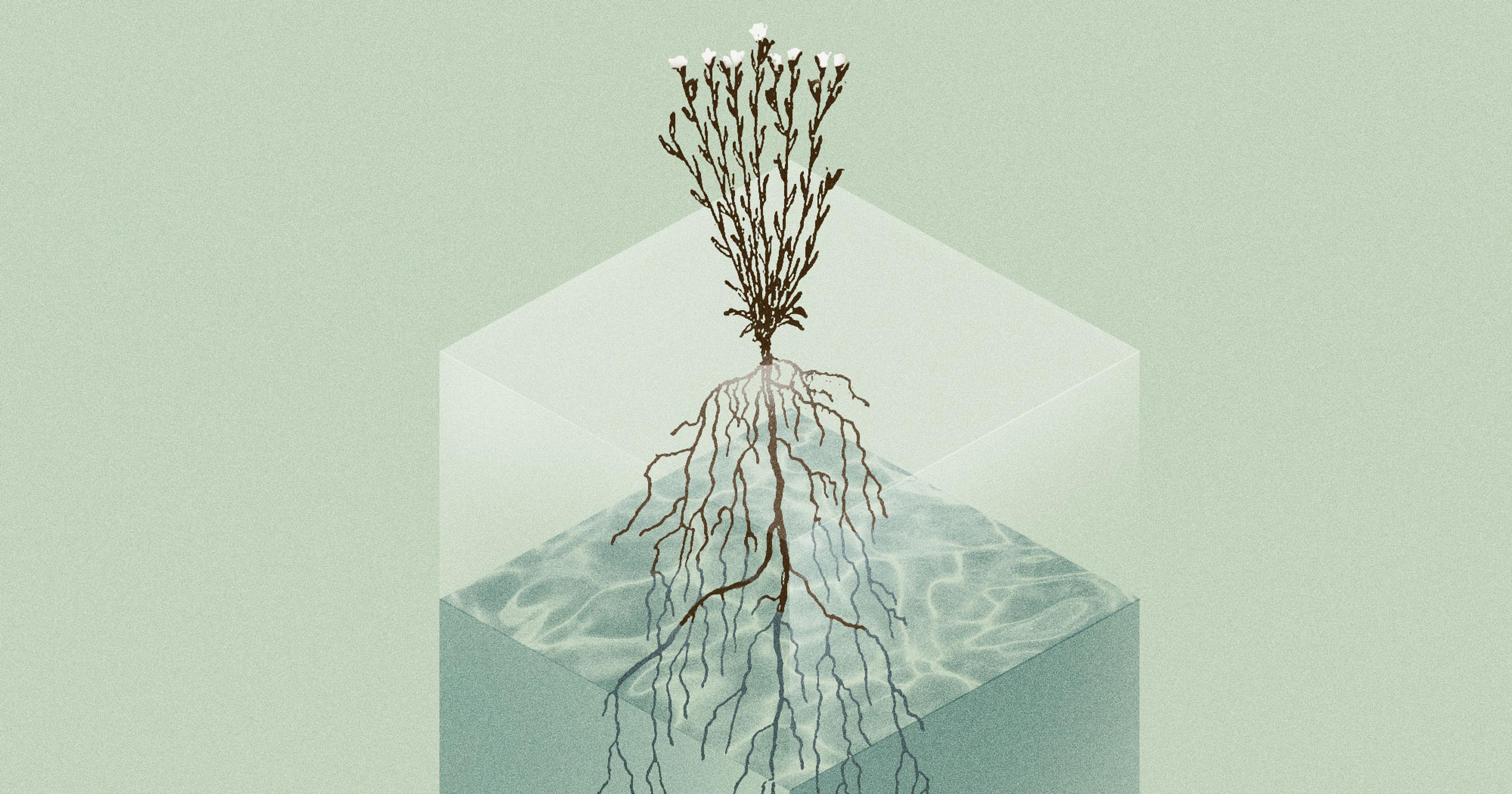

NASA is typically associated with looking outward toward the moon, the planets, and the stars, and, more recently, with crashing a rocket into an asteroid. But for everything it works on, the agency is not usually associated with earthly issues like agriculture and resource scarcity. Yet NASA maintains dozens of Earth-observing satellite missions and other sensors. These instruments focus on observing environmental conditions here on Earth, including collecting data about water resources and the hydrological cycle, which can help farmers plan better during the drought and other extreme weather conditions.

About half of the continental U.S. is currently experiencing drought, with about 30% in severe drought, according to the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor map. This drought “is a doozy,” according to Mark Svoboda, director of the National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC), which produces the Drought Monitor in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

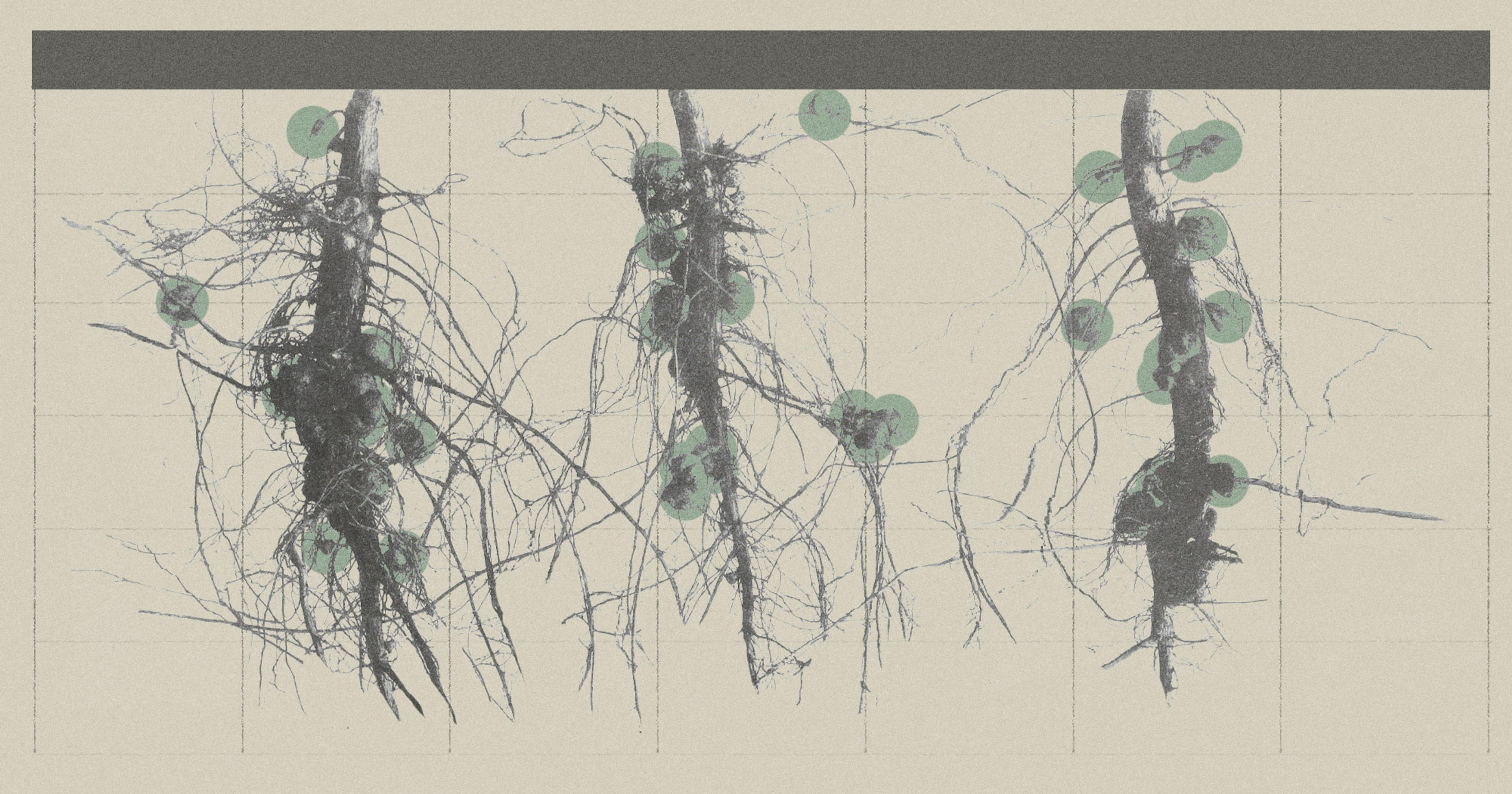

Although NASA is not an official NDMC agency partner, NASA data related to soil moisture, groundwater, and other aspects of the hydrological cycle also feed into the Drought Monitor. NASA’s tools “are helping us portray the drought situation more accurately on the weekly Drought Monitor map,” which is crucial for decision makers and individual farmers, Svoboda said.

NASA often funnels its data through other agencies and to the private sector — with little or no credit — for them to make that information available to the agricultural community, said Brad Doorn, program manager for water resources and agriculture in the Applied Science Program of NASA’s earth science division. That’s because agencies other than NASA might be responsible for water and irrigation management, for instance, according to Doorn. “NASA isn’t designed to provide operational support for the ag industry; USDA is designed to do that,” said Doorn. He added that NOAA is designed to provide weather forecasts, the Department of the Interior and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are designed to support water management, and the private sector is set up to provide support to producers.

During the listening tour, which signals a more direct approach for NASA, Doorn and others met with farmers in Nebraska and Kansas to learn about the challenges farmers face and information gaps they need filled. They also told the agricultural community about NASA’s longstanding involvement with farming.

“This nation’s space agency has an agriculture program, and the ag community needs to own it.“

Doorn said that NASA “has always been there” for the agricultural community, starting from the first weather satellites that helped improve weather forecasts. NASA’s other tools include a number of satellites such as the Landsat satellites and the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) observatory; OpenET, which provides satellite-based estimates of evapotranspiration for improved water management; and the NASA Harvest Mission, which works to improve food security in the U.S. and worldwide. In the works is a Harvest-like program specifically geared toward U.S. agriculture.

“This nation’s space agency has an agriculture program, and [the ag community] needs to own it,” Doorn said.

During a recent briefing, NASA Earth Science Division Director Karen St. Germain explained that the agency is “increasing the scope of our work in the agriculture sector because of the potential impact climate change may have on our nation’s ability to feed itself.” Doorn said that an additional factor in NASA’s increasing focus on agriculture is the evolution of NASA’s data and the concurrent demand on the ground for the data.

Farmers “are keenly aware that they are making use of satellite-informed decisions every day,” said Susan Metzger, associate director for agriculture and extension at Kansas State University, who has helped introduce NASA scientists to members of the ag community. Metzger added that she is less certain whether farmers are aware of the connection between NASA and the satellites.

For producers to be successful, especially with the scale of agriculture in the Midwest, they make use of data and technological tools at a robust scale, she said. Without that satellite information and other tools, “you wouldn’t be successful.”

Brothers Brandon and Zach Hunnicutt operate Hunnicutt Farms in Giltner, Nebraska, another site which NASA scientists visited.

“When it comes to NASA being the beginning of much of the weather data, I don’t think we had thought about it.”

Prior to the listening tour, the brothers had been somewhat aware of NASA’s importance, particularly regarding GPS. However, Brandon Hunnicutt noted, “When it comes to NASA being the beginning of much of the weather data, I don’t think we had thought about it.”

He added, “Really, everything that we’re doing on the farm starts with NASA. It starts with a satellite array somewhere up there.”

“The everyday, behind-the-scenes importance of NASA is something that we don’t recognize, but it’s hard to overstate,” Zach Hunnicutt said, pointing, for instance, to soil moisture estimates provided from NASA instrumentation.

In addition to NASA’s current tools, he — and others — would like more actionable information from NASA, including more accurate 14-day forecasts and improved spatial accuracy, and better ways to use the data.

“We are drowned in data” from satellites and from ground instrumentation, as well, said Ray Flickner. “Data for the sake of data can become overwhelming.” It’s got to be in a format that can actually provide information to make management decisions, he said.

“We have heard time and time again that the information has to be accessible, cost-effective, and make [farmers’] lives easier,” Metzger said. She and the farmers said NASA appeared to be listening to the ag community, and that there is promise for a continuing dialog. Ryan Flickner said he thinks NASA “very much wants to plant its flag, so to speak, within the agricultural space” and be an additional resource that producers and others can rely on.

Doorn and others at NASA said they hope the agency’s emphasis on actionable and applied science, and on solving real problems, can further help the ag community. “If we see farmers using our data, whether they know it’s NASA data or not, and are solving problems with that, that’s great,” he said.