Scientists say “bee vectoring” could help control pests — but how viable is it?

A bumblebee prepares to leave its hive. But first, it passes through a dispenser and picks up a dusting of biofungicide, a pesticide made of mycelium, that it will soon pass on to every strawberry flower it visits.

The pest-control formula will then be transmitted from flower to flower by other bees and different pollinators who visit next, hopefully preventing the farm’s strawberries from developing the gray mold no one wants.

When the bee returns to its hive after a long day of work, it enters through a different, pesticide-free entrance than it exited, so that new pest-control dust would not be brought in to contaminate the whole hive. This isn’t an accident; it’s a precise design for a method called entomovectoring, a buzz-worthy biological control solution to the pests and plant diseases destroying between 20 and 40 percent of the global annual harvest.

“As long as the crop has flowers that are visited by pollinators … then the possibility is there,” said Peter Kevan, a British-Canadian entomologist and professor emeritus at the University of Guelph, who quite literally (co-)wrote the book on entomovectoring. The method takes advantage of the fact that bumblebees, honeybees, and other pollinators visit thousands of flowers each day, making them an unexpected delivery system for fungicides and insecticides made from biological agents.

“Pollinating insects by their very activity spread tiny [pollen grains] between plants, so why not [use] them to disseminate other tiny particles such as microbes, that can serve to suppress plant pests and pathogens?” reads the introduction to Kevan’s book. He is referring particularly to microbial pesticides, which consist of a microorganism such as a fungus, virus, or bacteria as the active ingredient — the chosen agents depend on the particular pest being treated.

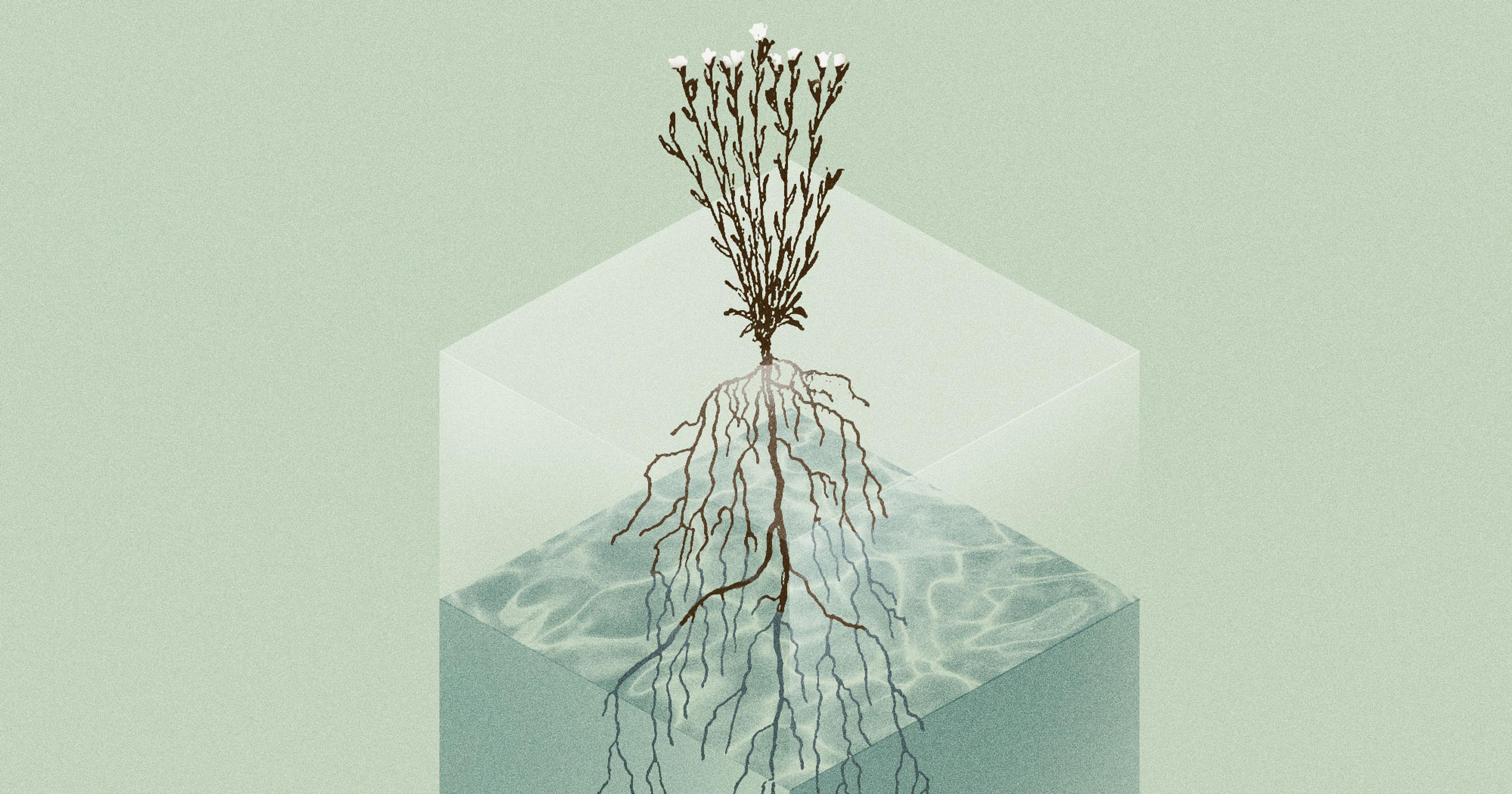

Since he first began studying this method two decades ago, Kevan has tested its potential on a number of crops including strawberries and greenhouse tomatoes, finding success with over 58% increased yield in some cases. Other studies around the world have also shown that biocontrol agents spread by bees can manage fire blight in apples, fungal diseases in tomatoes, and even borers in coffee plants when paired with specific microbial agents known to combat these issues. The method is being picked up across North America, Australia, Brazil, and Europe, and is now being evaluated in India, too.

“It’s taken off on a number of crops,” Kevan said. “People are becoming more and more interested in growing things without so much dependence on harsh chemicals.”

Along with crop protection without spraying en masse resulting in spray drift or run-off, this method claims to offer enhanced pollination. Bees spread pollen along with the protective treatment, which in turn improves crop yield and quality, especially for organic farmers who shy away from adding additional fertilizers and pesticides. Entomovectoring can also reduce the need for broadcast spraying equipment since hives are individually inoculated.

“Why not [use bees] to disseminate other tiny particles, such as microbes, that can serve to suppress plant pests and pathogens?”

The pesticides used through this method must be selected carefully, both for their effectiveness against the pest at hand and for their safety for bees. As a result, pesticides made of bacteria, fungus, and antibiotics have been the most successful. “It may be a little more management intensive in as much as there has to be somebody to look after the bees,” said Kevan.

Because of this, some are skeptical of how feasible this method really is. In 2024, Leisure Farms in Northeastern Ontario tried using entomovectoring to reduce aphids, which had been causing barley yellow dwarf disease in their oat fields. The hope was also to leave aphids‘ natural enemies, ladybugs, untouched.

The study showed a significant reduction in the population of aphids, but the family farm was left uncertain that the bee husbandry trade-offs were worth it. The scientists in this study did not track the impact of the bees on the final crop yield, leading to an incomplete picture for a farm that needs to closely monitor its bottom line.

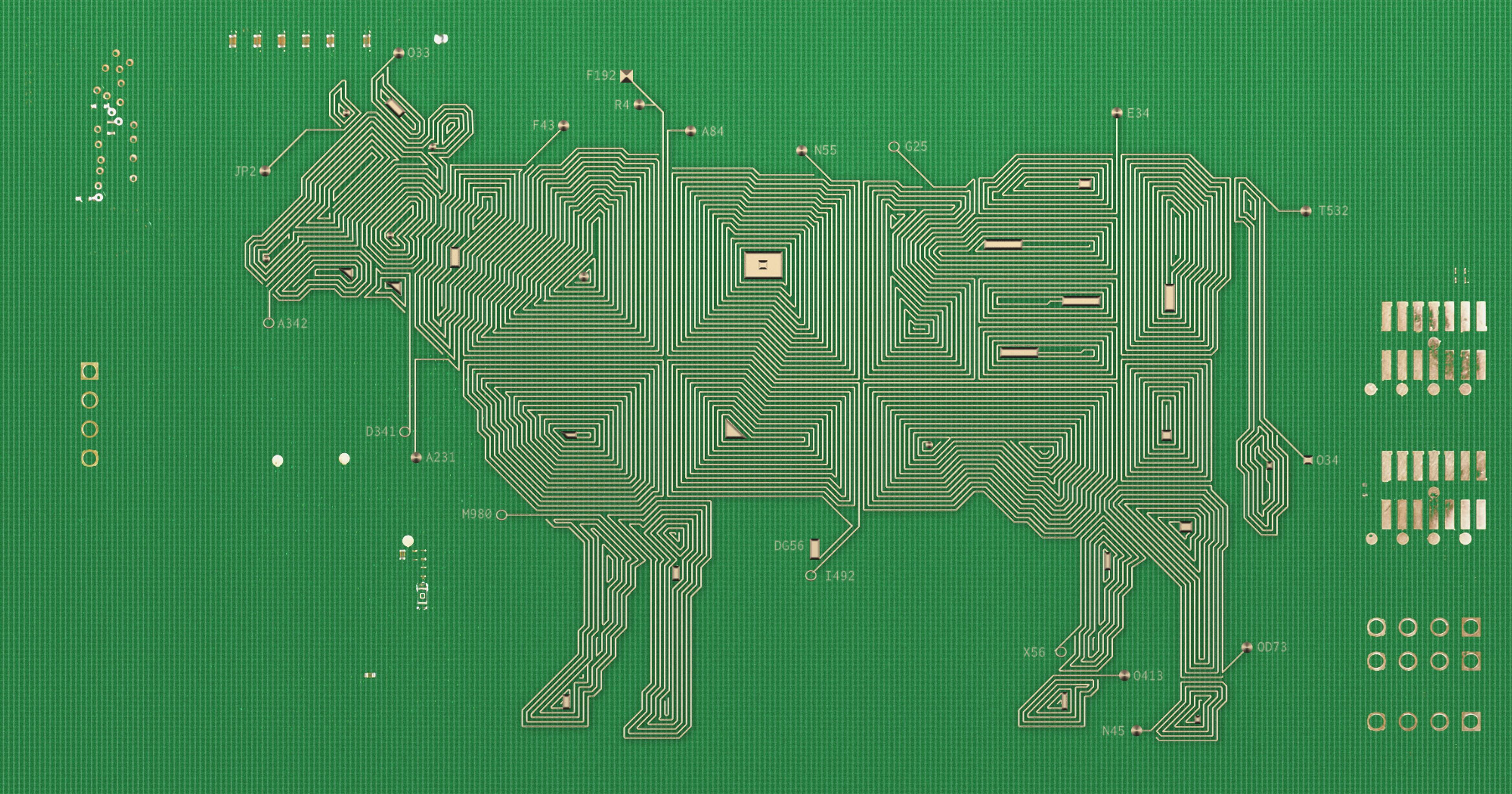

“Oats, wheat, barley, these are relatively low-value, high-volume crops. In other words, we have to produce it cheaply and productively, and if we’re managing bumblebees … that’s not productive,” said Ben Schapelhouman, agronomist for Leisure Farms. “I’m not all that interested in that, just because … even if it does work, it might be too expensive to carry out and not scalable,” pointing to the fact that there might only be specific use cases where it is actually profitable to raise and care for bees.

There are other limitations to bee vectoring. Sometimes, the pollinators can spread harmful pathogens to their hives, and other times they may not be able to fly through extremely hot or rainy weather. Chemical agents also often work faster than their microbial counterparts. In many places, there’s also a lack of existing support for growers who may want to implement and troubleshoot bee vectoring technology.

“We have to produce [crops] cheaply and productively, and if we’re managing bumblebees, that’s not productive.”

“Bee vectoring is not a silver bullet and, as such, should be used as part of a more holistic pest management program,” said Les Shipp, a former greenhouse entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in an earlier interview.

However, there are companies scaling bee vectoring successfully. One such company is BVT, currently in the process of getting permits to operate under regulations in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and European markets. It already has customers trying out bee entomovectoring with a proprietary powder mainly made of fungus. It’s been used on sunflowers, fruit, and even canola, another high-volume crop, and promises yield increases of at least 30 percent.

“It’s our job as farmers to distinguish ourselves and be different, to do something bigger, better, or more efficient than the next guy, so it’s a competition out here,” said Winn Morgan, co-founder of Major League Blueberries farm in Nicholls, Georgia, in an interview with BVT in 2021, adding that bee vectoring helped his operation switch to organic. “This technology using bees as a vector … it changed the way we farm here.”

“If you have a normal rate of 50 percent pollination success we’re having more like 65, 68 percent on most of our varieties here, and it’s throwing out a bigger crop,” Morgan said.

There is still lots of work to be done to determine just how widespread entomovectoring could become in helping solve pest management and pollination challenges. But, ask one of its many staunch proponents — they’ll argue that involving pollinators in our food systems in this new way could help us rise to the challenge of meeting global food demand.