Long scorned by ag-tech investors, the once-simple structure is taking over indoor growing.

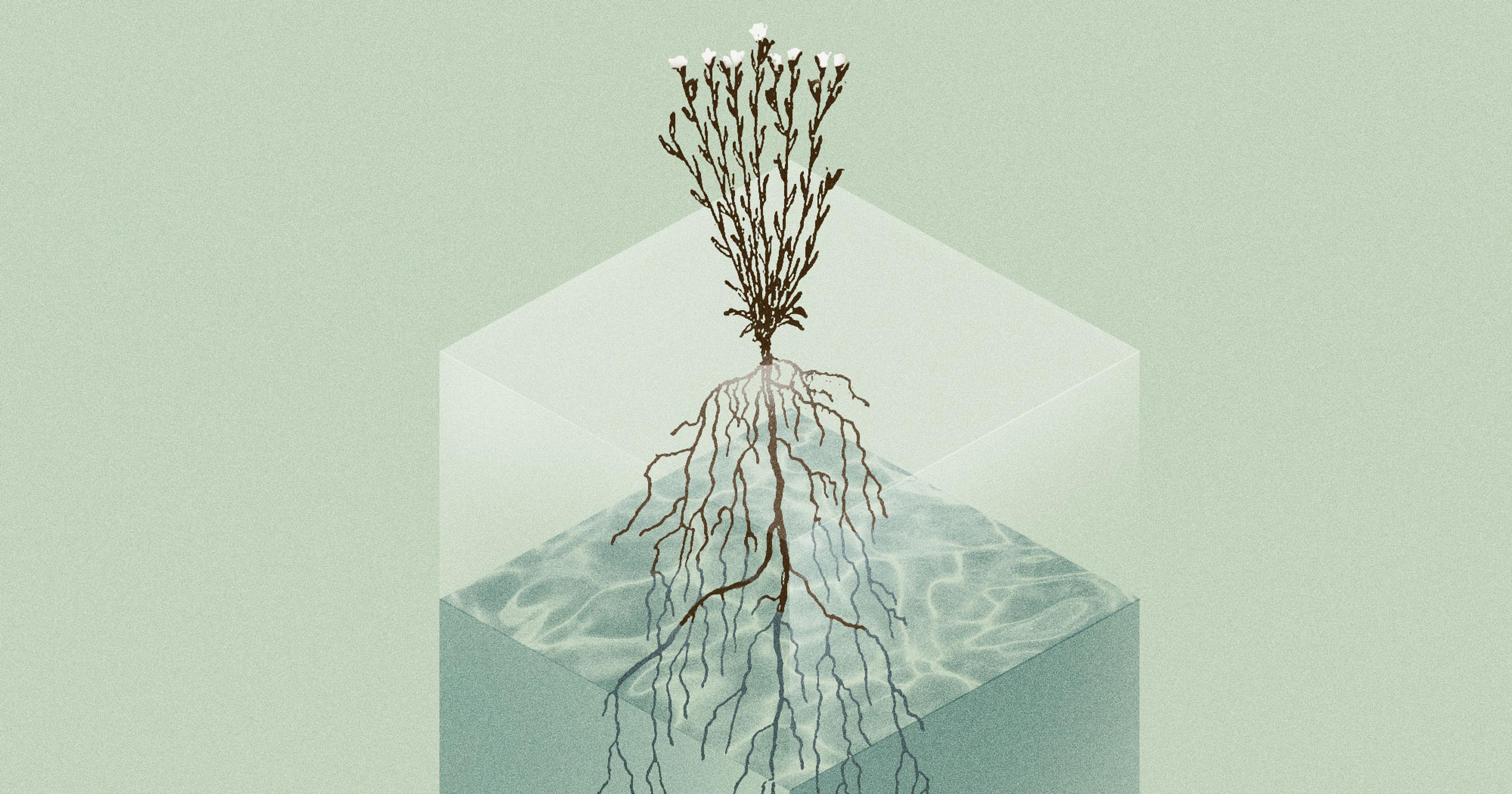

Around 30 A.D., the Roman emperor Tiberius decided he wanted year-round access to his favorite food: long-fruited melons, also known as Armenian cucumbers. Near his palace on the island of Capri, the emperor’s gardeners constructed wheeled beds with wooden frames covered by sheets of transparent gypsum, which let in sunlight and kept the vegetables warm even during the winter. These structures, called specularia, were the world’s first greenhouses, buildings designed to regulate the temperature and humidity of the environment inside.

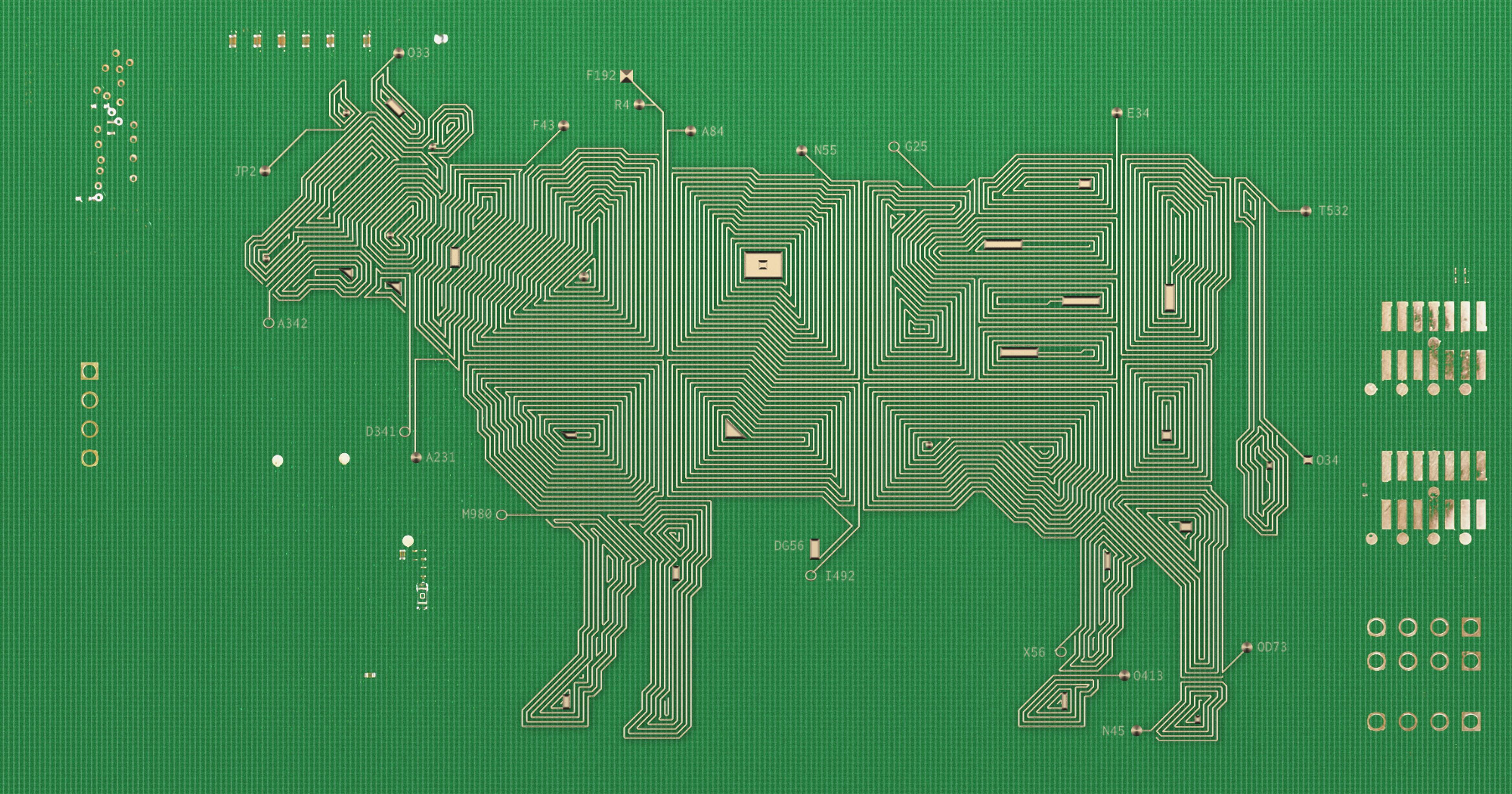

These days, greenhouses look a little different. In an airy, 8-acre facility in Texas, the roof is made of glass rather than gypsum, while fans, screens, and heating systems control the climate inside with precision. Leafy greens are grown in neat rows using a hydroponic system that replaces soil with a simple growth medium and delivers nutrients through water. When it’s time to harvest, a conveyor belt moves the lettuce underneath a mechanical blade and into the embrace of a robotic packing arm, which separates the greens into neat bags to be shipped to consumers.

This greenhouse is operated by BrightFarms, a company founded in 2011 which has since become a major player in the greenhouse-grown leafy green market. While vertical farms have struggled to break even, horizontal greenhouses like this one are booming, buoyed by advances in technology as well as energy and water savings that put them at an advantage. Aside from its Texas site, BrightFarms runs facilities in New Hampshire, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Illinois, boasting that it can deliver lettuce to two-thirds of U.S. consumers in as little as 24 hours after harvest.

As climate change makes traditional field-grown agriculture more risky and unpredictable, greenhouses like the ones used by BrightFarms are having a moment. According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, the number of “controlled environment agriculture” operations, where plants are grown indoors under carefully monitored conditions, doubled from 2009 to 2019.

Both greenhouses and vertical farms fall under the umbrella of “controlled environment agriculture,” or CEA. But there’s a key difference: While vertical farms stack plants on top of each other and rely entirely on artificial light, greenhouses tend to spread out horizontally and utilize some sunlight, with additional lighting provided when necessary.

That arrangement makes vertical farms more suitable for growing crops in the middle of urban areas where space is limited, endearing them to tech companies and start-up investors who saw their potential to “disrupt” agriculture. The hype, though, by and large hasn’t paid off; a number of vertical farming companies have gone under in recent years, plagued by high energy costs and consumer indifference.

Greenhouse-grown lettuce ... is now seeing “explosive growth,” increasing five-fold in the past five years.

“Greenhouses have continued to grow because we now have exceptional control over the climate” inside them, said Abby Prior, BrightFarms’ chief commercial officer. At the same time, they have advantages over vertical farms because they still rely on sunlight as their primary energy source. “Sunlight is free. It’s how we’ve been able to scale this business and also build a business model that’s financially sustainable as well as a better solution for the planet.”

The first greenhouse in the U.S. was built in Boston in 1737, and by the 19th century, greenhouses were common around the Northeast, allowing farmers to sell fresh produce in the cities even during the off-season. Then, starting with the Great Depression, the value of greenhouse-grown vegetables trended steadily down, said Neil Mattson, director of the CEA program at Cornell University. The nationalization of the food system, with year-round produce being grown in California and Florida and shipped by refrigerated trucks across the country, made them less necessary.

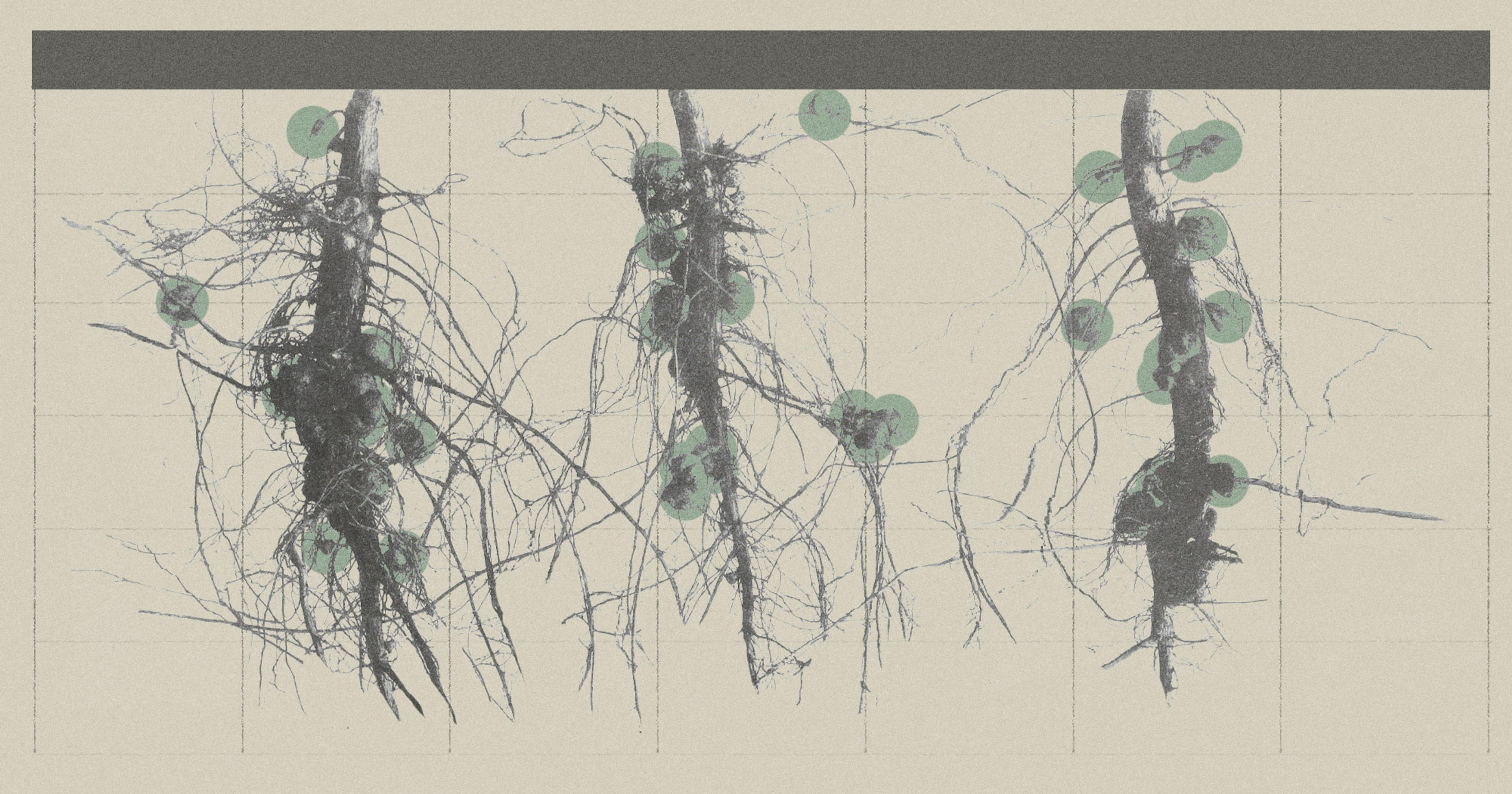

But since the 1980s, that trend has reversed, with new greenhouse technology imported from the Netherlands — the world leader in CEA — driving down costs of production and encouraging the expansion of some greenhouse crops, particularly tomatoes. A majority of the fresh tomatoes Americans eat now come from greenhouses, Mattson said, and though greenhouse-farmed lettuce holds a much smaller share of the market, it’s now seeing “explosive growth,” increasing five-fold in the past five years.

There are a few reasons behind this shift, Mattson explained, starting with consumer preferences. The popularity of bagged salads has led to greater demand for fresh, varied, and flavorful lettuce at any time of the year; growing greens indoors near major urban centers rather than trucking it in from California allows them to stay on store shelves for longer, leading to a better experience for buyers as well as less waste for retailers.

Climate change, meanwhile, is wreaking havoc on traditional lettuce-growing regions like California’s Salinas Valley, with erratic weather patterns shifting between droughts and torrential rains. This has made harvesting more difficult, encouraged the spread of diseases, and led to worries about water use, as California grapples with high demand from its agricultural industry. And the Covid-19 pandemic caused supply chain disruptions that exposed the fragility of a centralized food system, pushing some suppliers to focus more on distributed, local production.

A majority of the fresh tomatoes Americans eat now come from greenhouses.

At the same time, greenhouses still face some challenges. In 2020, Mattson and his colleagues at Cornell published a study showing that in major urban areas, greenhouse-grown lettuce was still at least 50 percent more expensive than field-grown lettuce because of higher associated costs of electricity and labor. Companies like BrightFarms or Gotham Greens have to charge at a similar price point as organic produce, and rely on consumer willingness to pay more for lettuce that’s labeled “local” or “pesticide-free.”

Technological advances, though, could eventually bring these costs down as greenhouse production expands through economies of scale, Mattson said. Inside, greenhouses today don’t look like the simple constructions of yore; they’re integrating much of the technology typically associated with vertical farms.

Lamps made with light-emitting diodes, or LEDs, have become widespread in the last 10 years and use much less energy than older incandescent bulbs, bringing electricity costs down and allowing greenhouses to operate year-round. Climate control systems regulate the humidity and even the carbon dioxide levels in a greenhouse, maximizing crop yields. And automated systems, like those utilized by BrightFarms, use robots at all stages of the growing process, from seeding to harvest and packaging, reducing the need for human input at a time when farms are facing labor shortages.

“Greenhouse technology has gotten so sophisticated,” said Tom Stenzel, executive director of the Controlled Environment Agriculture Alliance, an industry group that was founded in 2019 to represent leafy greens growers and has since expanded to include all kinds of indoor crops. “It’s not the old plastic cover — you’re controlling everything.”

At the same time, developing these systems requires a huge up-front cost, which can be a barrier for growers trying to enter the industry. That’s why Stenzel’s organization is lobbying for government support for CEA — for example, by pushing for USDA programs to encompass indoor agriculture as well as outdoor. And more recently, Stenzel said, they’ve had to speak out against Trump’s tariffs, which would raise the cost of imports from countries like the Netherlands that supply greenhouse technology and make the business more expensive for growers.

In major urban areas, greenhouse-grown lettuce is still at least 50 percent more expensive than field-grown lettuce because of higher associated costs of electricity and labor.

So far, the greenhouse-grown lettuce market seems to be expanding alongside traditional field-grown lettuce, rather than replacing it. But Stenzel and Mattson don’t expect that to continue for long. Modern greenhouses require less water, less fertilizer, and little to no pesticides, putting them at a long-term cost advantage and aligning them with consumer preferences. And particularly in areas of the world with little water and abundant energy — the Middle East, for example — indoor agriculture is much more pragmatic than outdoor.

In the U.S., companies like BrightFarms are also expanding into new areas, focusing on building a network of regional greenhouse-grown salad “hubs” that bring their product closer to consumers. Freshness and quality, they believe, will give them an advantage over still-cheaper field-grown lettuce.

“There is value in being able to eat every single leaf in the container,” Prior said. “And in the product looking beautiful in your refrigerator even well past the sell-by date.”