Dungeness crab season was a beloved Bay Area holiday tradition, an annual $40 million boon for crabbers and restaurants alike. But with Humpback whales getting entangled in crabbing lines, the tides have shifted.

Growing up in the Bay Area, Dungeness crab was found on the dinner table every holiday season. On Christmas Eve, with friends and family, we waited excitedly for the night to fall and consume crab and butter accompanied by my family’s homemade Caesar salad. We’d debate over the best sauce, who would eat the most, and, importantly, if it was best to pile the meat or eat as you go. It was a longstanding tradition, not only in our household, but in households across the greater Bay Area.

“I moved here in 1996 and only then learned about how San Francisco celebrated Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and New Year’s Eve with Dungeness crab,” said Kenny Belov, part owner of Fish Restaurant and TwoXSea fish distributor in Sausalito, California.

But in recent years, this tradition has been put in peril.

“With the ups and downs and the seasons of late, that tradition of having local crab for the holiday season has become a thing of the past, which is very hard for me to stomach,” Belov said. “There’s a full generation of people now who know nothing about that tradition.”

What was a cherished local winter staple and a critical source of income for local fishermen and their communities has slowly evolved into an annual struggle. Over the past six years the local California Dungeness crab fishery has been mired by late starts and early closures. The cause? An increase in whales becoming entangled in the lines of crab traps and other fishing gear. The delays have turned an historically six-month fishery into just a four-month one. Crabbing for Dungeness will likely have a late start again, in early to mid-January, entirely missing the lucrative holiday season.

Whale entanglements have been part of fishing off the California coast for many years. In fact, in 2016, entanglements rose to their highest numbers ever. They used to typically happen in spring, as hungry whales returned to their feeding grounds. However, it wasn’t until 2019 when entanglements began to occur more commonly in the winter, leading the California Department of Fish and Wildlife — which oversees the management of California fisheries — to delay the crabbing season to reduce the amount of fishing gear in the water entangling whales. Since then, there have only been two on-time starts to the season, almost entirely due to whale entanglements.

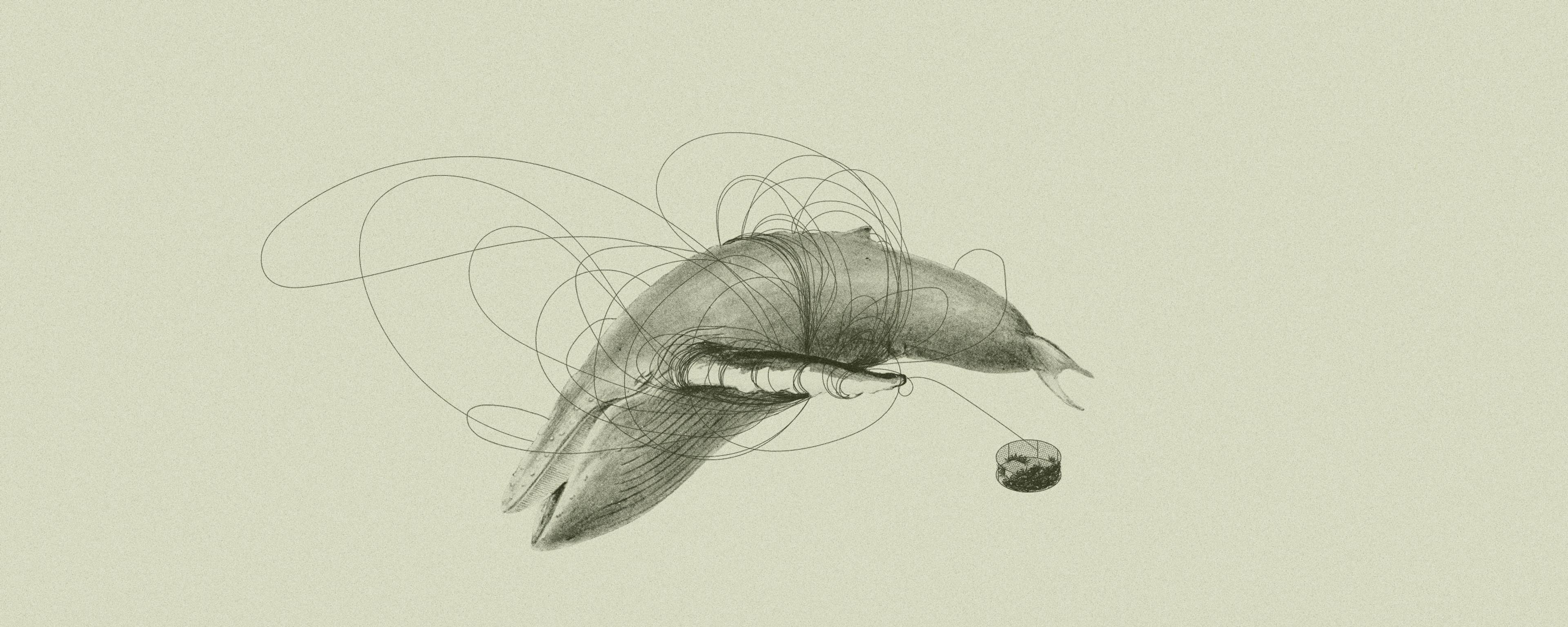

Whale entanglements are what happens when a whale gets caught up in any kind of fishing gear. This can cause something as mild as strain on the animal, but often can lead to death from getting trapped. Usually this is from vertical lines, long ends of rope, propped to the surface with a buoy and fixed to the ocean floor by the weight of a crab trap, often referred to as a pot.

“It used to be that we rarely would see a whale,” said Dick Ogg, Bodega Bay-based fisherman and a member of the Dungeness Crab Task Force, a working group between state and federal agencies, conservation groups, and crabbers. “Now we see them all the time, everywhere we go.”

“With all the delays and closures, it feels like a ghost town now during what used to be our busiest season.”

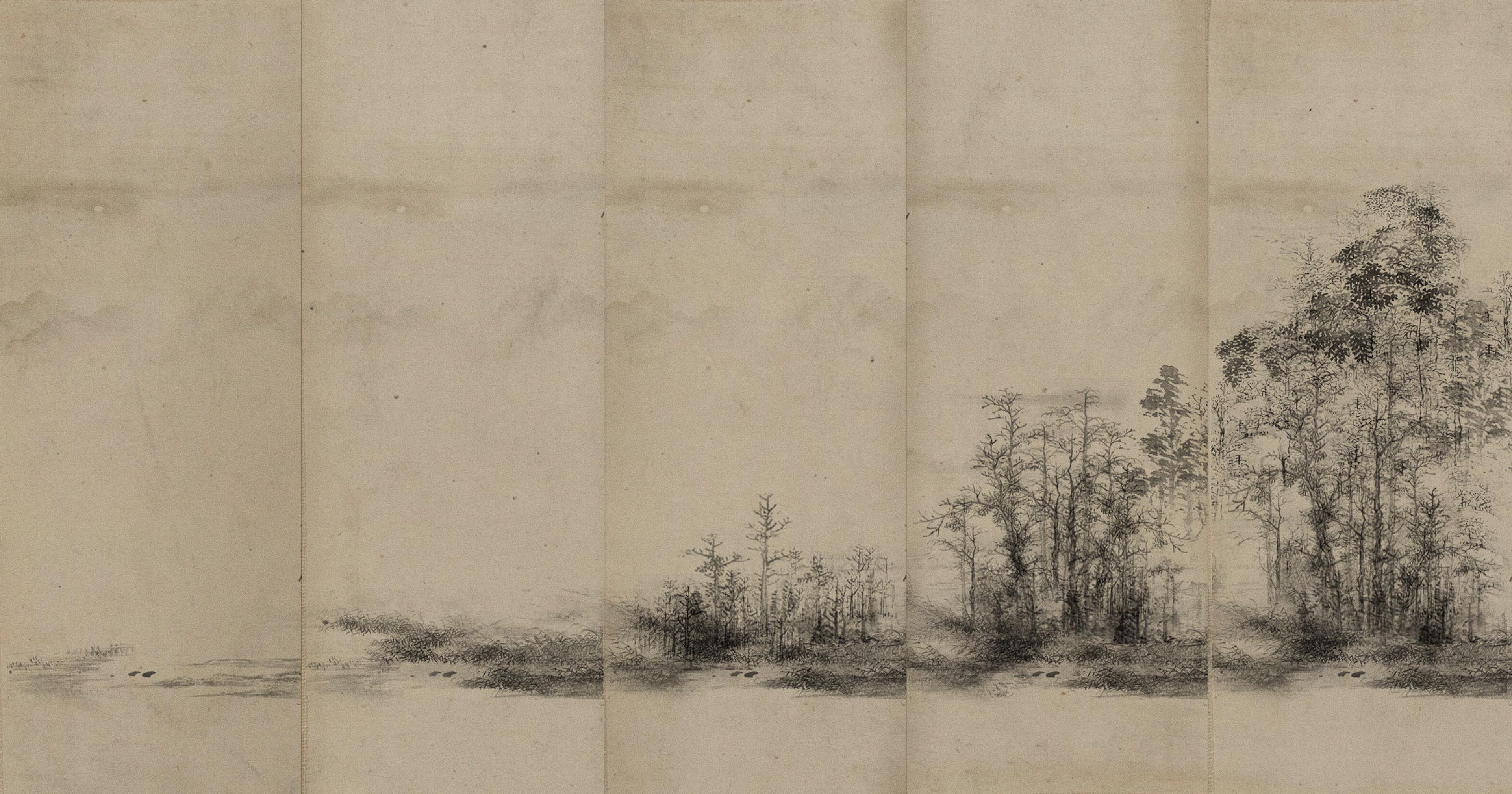

For many observers, this shows that whale conservation efforts are proceeding well. This may not be entirely true. From 2012 to 2021, scientists observed a decrease in the population of humpback whales by nearly 7,000 individuals, or close to a quarter of their population. Scientists widely believed this was caused by a massive marine heatwave in the region, ominously called “The Blob,” which impacted what they ate, and in turn harmed their numbers. After this event their numbers began to rise, but scientists noticed that the whales were coming closer to the coastlines to search for food, putting them in contact more often with Dungeness crab traps and other fishery lines. This has created the situation the Dungeness crab fishery is in today: a shortened crabbing season leaving many crabbers — who might only catch Dungeness crabs and may not have knowledge of other fisheries — out of work.

As the years have gone on, Ogg said, the crab fishery has been doing much better to avoid whale entanglements by spreading out where they place their lines, ideally leaving more room for whales to pass. The Dungeness fishery is so popular, however, that this is not always possible.

“There is not one fisherman that would say, ‘Oh, yeah, I want to go out and entangle an animal,’” said Ogg. “We’re doing everything we can to minimize our potential interaction.”

It is important to note that many other fisheries cause entanglements as well. That said, the Dungeness crab fishery has historically been the most detrimental to whales due to the sheer number of crabbers going out during the first days of the season. According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Dungeness crabbing season gives out anywhere from 350 to 700 permits any given season accounting for many thousands of traps and lines in the water, making around $40 million in a decent year. Compare this with one of California’s other lucrative fisheries, market squid, which makes on average $60 million, but usually gives out 150 permits.

In a recent press release from NOAA fisheries, confirmed whale entanglements in 2024 were up to 95. “This is higher than the 64 confirmed large whale entanglement cases in 2023. It is also above the average annual number of confirmed entanglements over the previous 17 years, which was 71.4,” the press release states. These numbers are a total for the whole of the United States, but 25 percent, the greatest contribution from any region, occurred off the West Coast in California waters.

For Belov, the delays impact his sales during the winter; luckily his businesses have gained back those lost months in February.

“There is not one fisherman that would say, ‘Oh, yeah, I want to go out and entangle an animal.’”

“I’m now, as a wholesaler, selling Valentine’s Day crab,” Belov says. “For our first 15 years of business, we never saw our fleet fishing through Valentine’s Day. They were long done by then, getting ready for salmon. So it’s not so much that we’ve lost sales. We’ve just shifted when we have those sales.”

He also emphasized the importance of accepting and moving with the changes in a shifting market. “I am a huge proponent of change, and that you always have to be growing your businesses and adapting to changing conditions. Doesn’t matter what business you’re in,” said Belov. “You always have to have an eye on the future. And if you don’t have an eye on the future, you’re going to be left behind.”

Belov, however, is fortunate to have a restaurant in Sausalito, a wealthy suburb and tourist destination just outside San Francisco. Having so many more potential customers to serve on a weekly basis may mean that he is in a more fortunate position than others.

For decades, the crabbing season brought in vital tourism to more remote coastal communities across the Bay Area. Gurpreet Singh, owner of Fishermen’s Cove restaurant and tackle shop in Bodega Bay, said he has lost around half of his revenue during the November through January holiday season due to entanglements.

“With all the delays and closures, it feels like a ghost town now during what used to be our busiest season,” said Singh. “It’s affected a lot of people’s livelihoods, including ours.”

“You always have to be growing your businesses and adapting to changing conditions. Doesn’t matter what business you’re in.”

With a late start this means that, rather than make that money back later in the season, Singh just outright loses it. Since Bodega Bay is a small town far away from the urban hubs of the Bay Area, businesses there rely heavily on tourist dollars to stimulate the economy. As the holiday season is the most common travel time for people around the country, this is a very important time of year for restaurants and businesses in the North Bay. Losing out on the crabs has meant that the whole of the community is impacted.

While the impacts of the entanglements are great, solutions are on the horizon. Conservationists and a growing number of fishermen believe that the relatively new technology of pop-up crab pots may be the answer to the issue of entanglements.

Since 2018 many crabbers in conjunction with conservation groups and fisheries have been experimenting with this new technology during the spring season. Crab pots are dropped to the bottom of the ocean with a long rope, often with a buoy attached to the top for easier retrieval. This line, as noted earlier, is the key cause of entanglements. Pop-up pots are simply crab traps with no vertical line, thus reducing the threat of entanglements. This new kind of pot drops to the ocean floor with a line and buoy trapped inside of it. When the crabber is ready to haul in the pots, they can release the buoy via a sonar signal, bringing up the rope only for the necessary moment of retrieving the traps, greatly reducing the chances for whales to get trapped in the gear.

Over years of experimentation under experimental fishing permits, many crabbers have found it to work fairly well. However, this tech is only for the spring season, when the waters are less choppy, and the chances of whale entanglements are typically greater.

“This was never going to be solved by the government, by, you know, the people making the technology, by the NGOs, right? It was really a few fishermen that decided to step up.”

Oceana, an ocean conservation organization, recently released results of a study of pop-up crab pots and their economic viability for the spring. It shows that across California during this last spring season, when the waters were closed for conventional crab traps, pop-up pots brought in 1.4 million dollars of crab, showing that the traps can be economically effective while an area may be full of whales.

“This was never going to be solved by the government, by, you know, the people making the technology, by the NGOs, right? It was really a few fishermen that decided to step up,” said Geoff Shester, California campaign director for Oceana. “And I think a lot of fishermen took a big risk by going out there and trying this — a financial risk, a risk within their own community. And they really brought this from a concept to something that now looks like it really could be the future for the fishery.”

Fishermen are still hesitant about using ropeless pots in the winter, due to large swells and safety concerns. Regardless, it is a cause for hope that, at least for the spring season, the crabbers could remit their losses slightly as more of them take on this new style of equipment.

The crab fishery itself has been remarkably stable since it began to be regulated by the state in 1895. However, as the climate begins to warm, these sorts of impacts will increase. What we know currently is that the season has shortened. Along with that we are watching the local environment change alongside local economies and traditions.