As the Trump administration fast-tracks mining for this potent fertilizer, advocacy groups sue over lack of environmental oversight.

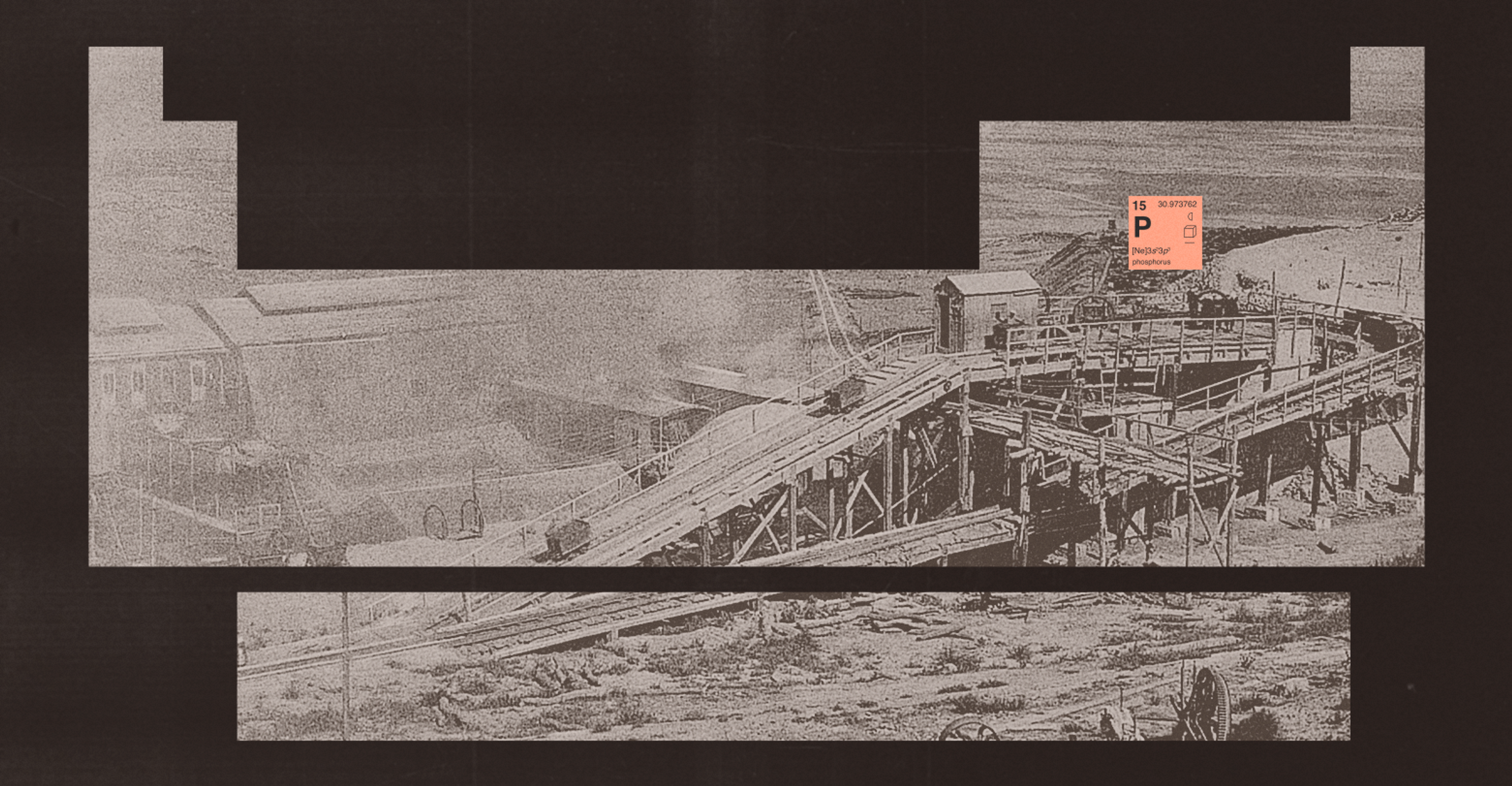

William Harrison tells a quaint story about a pink-hued mineral. In 2008, the research director of the Michigan Geological Repository for Research and Education got a call from an intern at a company that had built, then sold, a mine in the western part of the state. Did Harrison want their historic collection of core samples? Harrison turned up in his too-small pickup to find 4,000 boxes filled with cores drilled over a mile deep from a mineral deposit known as the Borgen Bed. Once (arduously) stored, the boxes were visited by representatives of another would-be mining outfit. Scientific analysis revealed that the samples were replete with high-quality potassium chloride. When processed to remove impurities, this becomes potash — a fertilizer rich in potassium, which is a primary nutrient for plant growth. And thus, the Michigan Potash and Salt mining company was born.

Certain members of the farming community expressed elation over the venture. Agriculture publication FarmProgress enthused over the company’s proposed operation for its “potential to reduce imports of potash, improve the nation’s trade balance, create jobs, greatly increase the state’s tax base, improve the rural economy, and provide farmers with an easily accessible U.S. product”; CropLife deemed it essential to national security. Michigan Potash’s new plant was supposed to come online sometime around 2017, provide a few hundred jobs, and produce over half a million tons of potash a year (eventually upgraded to 1 million tons). Nine years later, construction has yet to begin.

But a March 2025 executive order from the White House designating potash a “critical” mineral; a promise of some $1.4 billion in federal and state loan guarantees, tax-exempt bonds, and subsidies; and a sudden flurry of expedited permits means that this mining operation might come into being after all. It’s a possibility that some, like Ken Ford, a forester and member of action group Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation, are less than thrilled about, because of the potential for the mine to pollute drinking water and impact wildlife. “People around here want to know exactly what’s going on,” he told Offrange, and they don’t like what they’re hearing.

“Simply replacing foreign-made inputs with domestic ones only partly addresses the issue.”

U.S. farmers use 4.75 million tons of potash fertilizer a year, mostly on corn and soybeans, to help with photosynthesis, starch formation, root growth, and other plant functions. Not every farmer believes potash mining on American soil or elsewhere is worth the expense, effort, and environmental cost. “Nobody that values soil as a regenerative resource — a capital investment — who respects the land, would use refined potash on soil, any more than they would use urea in production farming,” one California farmer told Offrange.

Lara Fornabaio, a food and environmental lawyer at the Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment, agrees. “Simply replacing foreign-made inputs with domestic ones only partly addresses the issue,” she said. “Inputs remain costly, and over time their impacts on soils and ecosystems can actually undermine the very productivity farmers depend on.”

According to a new USDA report on the fertilizer market, the U.S. is “heavily dependent on imports to meet potash fertilizer demand.” The small amount of domestic potash we use comes from mines in New Mexico and Utah, and our reserves of the stuff are around 220 million metric tons. We export zero potash. The remainder is imported mostly from Canada (75% in 2021, now subject to a 10% tariff), Russia (despite the war in Ukraine), and Belarus (currently sanctioned).

Michigan Potash’s founder, Ted Pagano (who did not respond to Offrange’s requests for comment), told the Kalamazoo Gazette back in 2013 that his plant would produce “a Michigan product for Michigan farmers that would dramatically reduce the expensive transport costs on the more than 300,000 tons of potash consumed in our state annually.” In the intervening years, another 700,000 tons has apparently found an eventual buyer in Illinois-based food processor ADM, according to Forbes.

Pagano also insisted to that outlet that his mine would be virtually imperceptible on the ground, an idea that makes Ford balk. The operation has leased 14,500 rural acres, about 80 of which are earmarked for the mines themselves, and the refinery. A neighbor was reportedly told by Pagano himself, “You’re going to smell it, you’re going to hear it, and in fact, you’re going to see it.” Transporting potash away from the plant — which will be sited amid 50 pristine wetlands — will require, by the estimate of one local county’s road commission, about 80 round-trip semis a day, “roaring through our peaceful little neighborhood,” said Ford. This means no one in the community is a “real happy camper.” In fact, Ford’s organization petitioned the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s oversight body, the Environmental Appeals Board, to review six permits that it believes were granted to the company without proper environmental review.

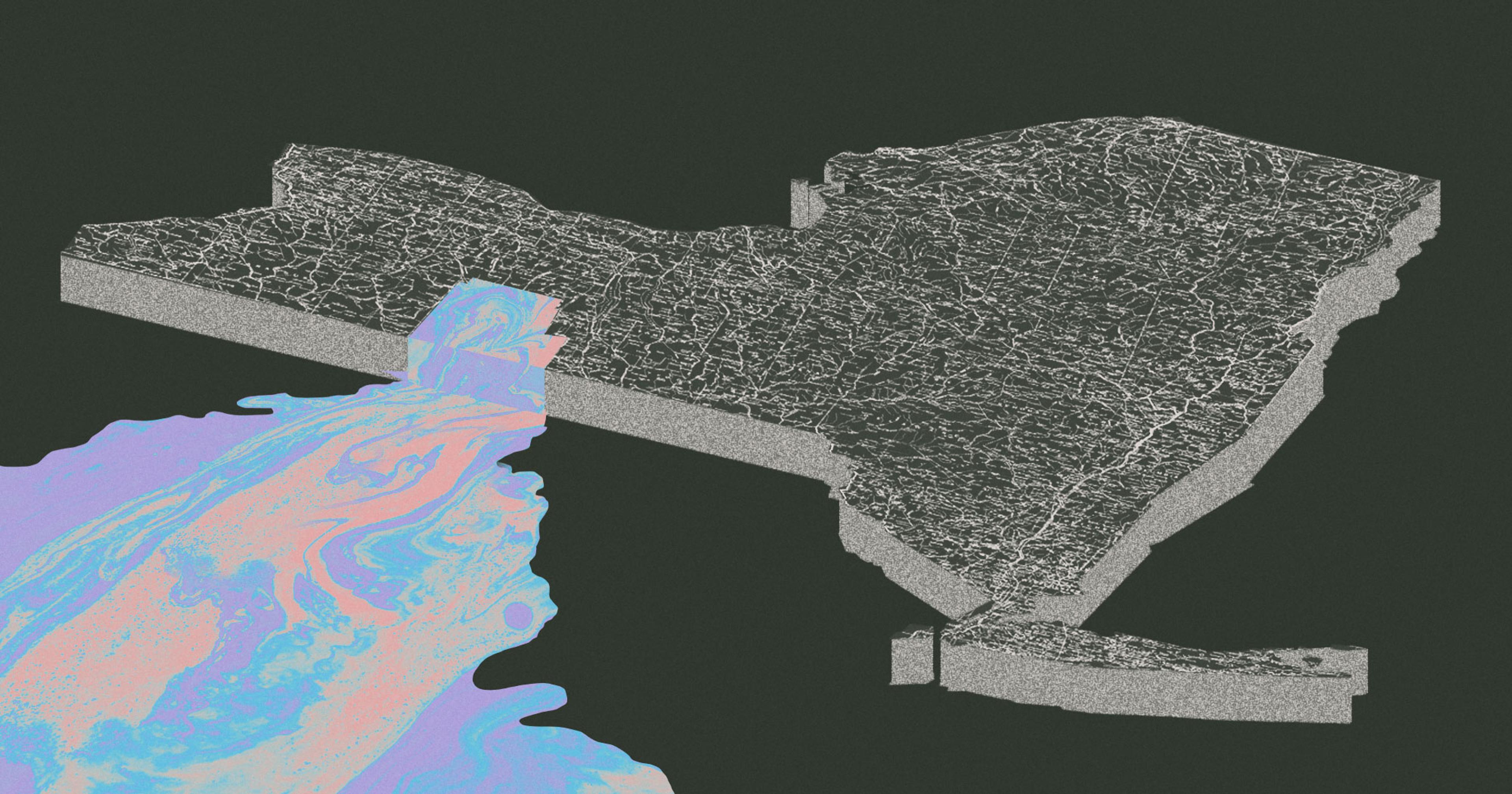

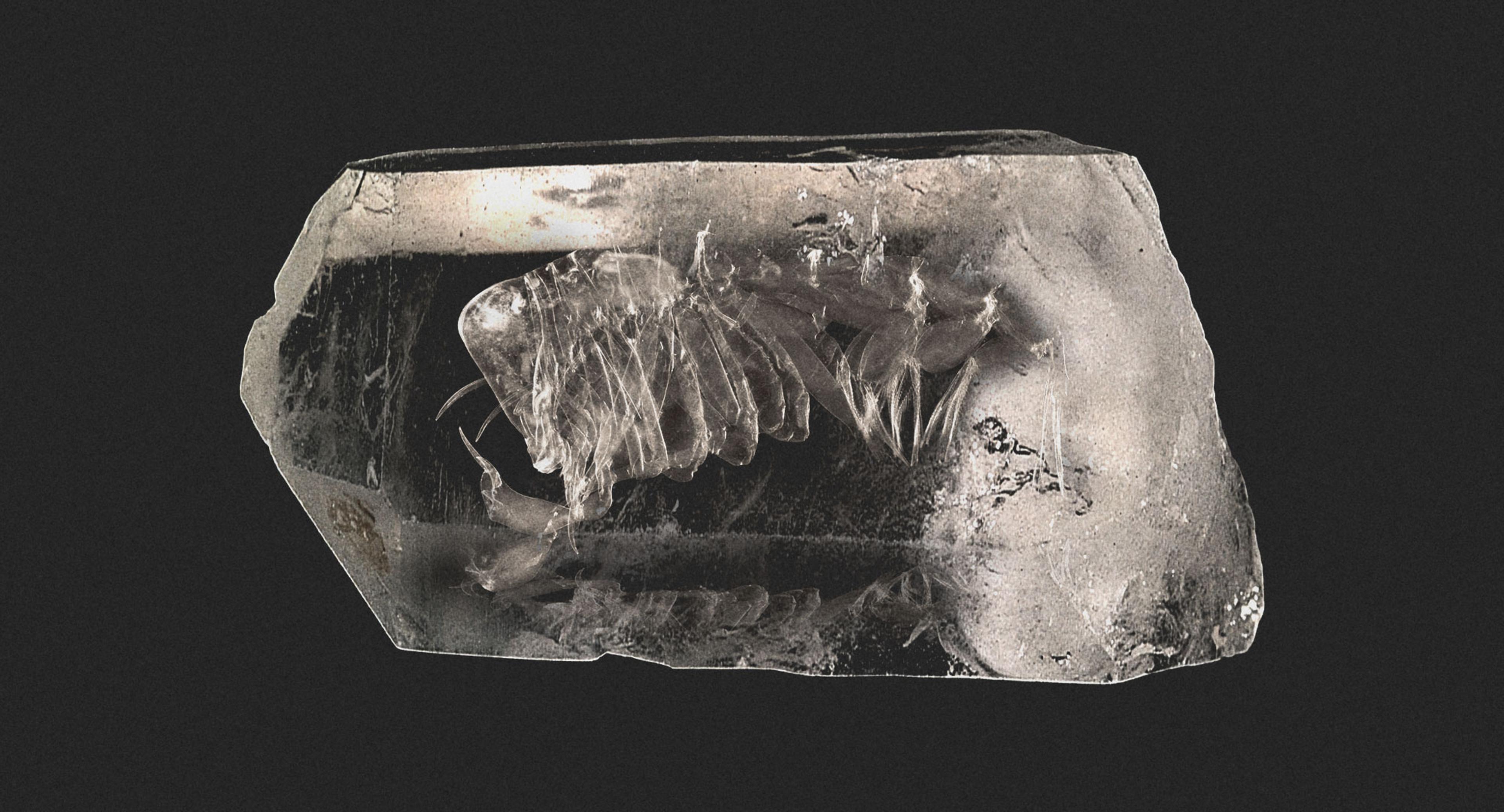

Steven Emerman is a hydrologist and mining consultant based in Utah. He said that solution mining, which is what Michigan Potash intends to use in its operation, is, “on the scale of mining operations, getting toward the more benign end. That doesn’t mean there’s no problems.” Water — in this case, almost 2 million gallons a day, drawn from an aquifer separated by only 170 feet of clay and sand and gravel from another aquifer that supplies drinking water to two counties — is pumped into the ground to dissolve potassium rock. The resulting salty solution is pumped back up and the water is evaporated; what’s left behind are potash crystals. In the case of Michigan Potash, any waste, known as tailings, would be injected deep underground via disposal wells, the likes of which have a habit of leaking.

Emerman’s worried that pipelines transporting corrosive brine, which have a high failure rate, could effectively poison drinking water. “Do you actually have a safe route where a rupture is not going to destroy anyone’s water supply? What rivers are you going to cross? That’s all of what should be in an environmental impact study,” he said. Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation’s petition to EPA alleges that the agency’s environmental review was inadequate to protect community water sources; since then, EPA confirms the permits for the company have been withdrawn. MCWC’s counsel hopes this will trigger a new application and review process, which EPA declined to comment on.

Emerman’s also concerned about the ground sinking as material is extracted, known as subsidence. According to Harrison, potash will be taken from a depth of 7,600 feet, where “the structure of the earth is much more stable.” Countered Emerman, “If someone says there’s no subsidence, where’s the report, where’s the study? And if there’s no report, then it’s just gossip. It’s a rumor.” The materials supplied by the company are unpersuasive, he said. Ford fears that subsidence could cause the lower aquifer, which contains salts and arsenic, to leak its contents into the drinking-water aquifer above.

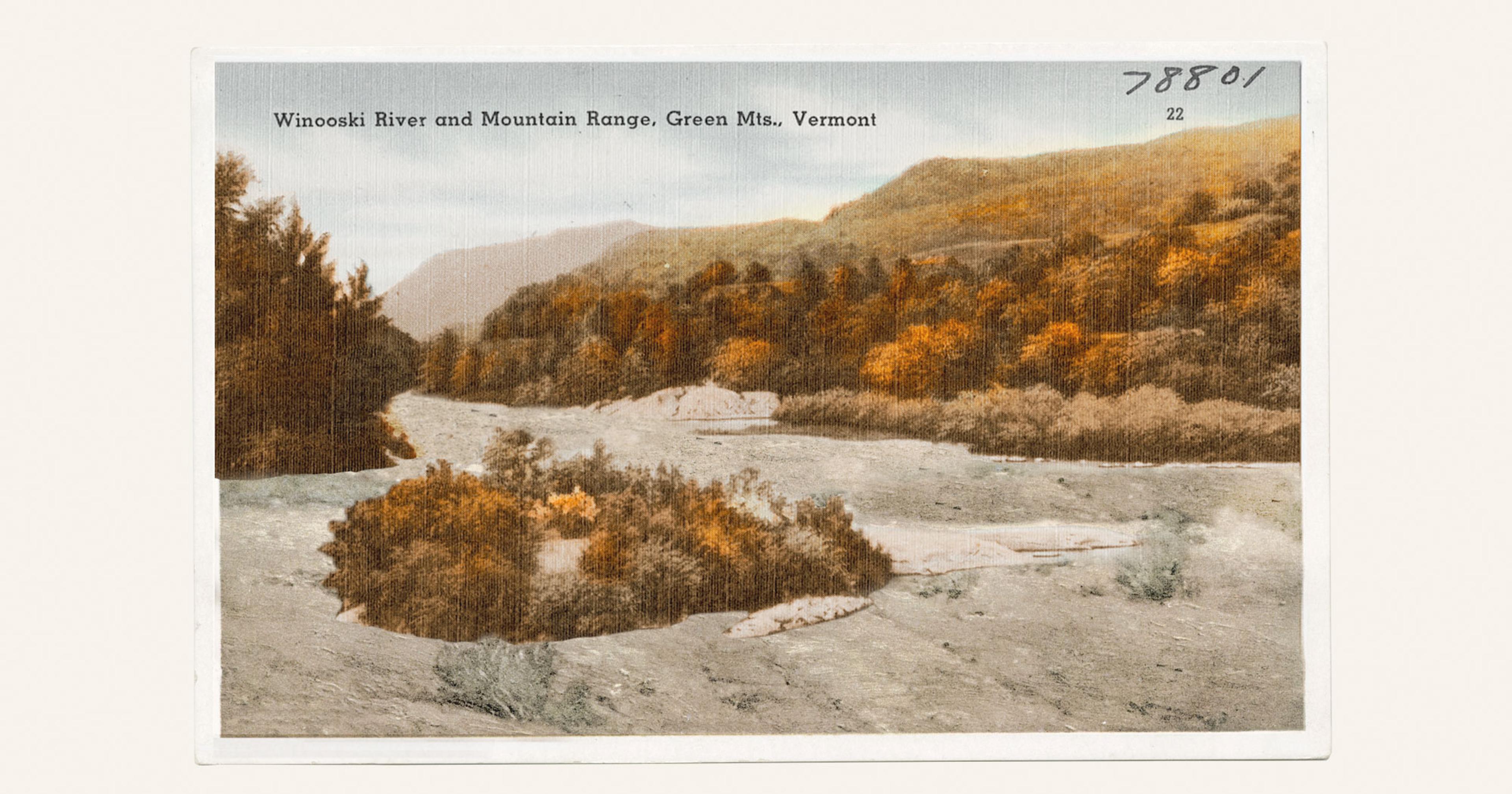

Emerman has greater concerns over another planned potash mine in a proposed wilderness area and critical bird migration stop in Western Utah. Similar to Michigan Potash, Peak Minerals has been trying to launch its mine for over a decade, on the Sevier Playa. Its website promises a “positive environmental impact,” although it plans to use a destructive method of brine mining, in which deep trenches are opened up and filled with fresh water to create a potassium chloride brine, which then evaporates in ponds. Similar mines contain waste behind earthen dams that have a history of failure, with devastating environmental results.

“This is very, very much a surface-disturbing operation,” said Hanna Larsen, staff attorney at the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance. The plan here is to extract increasing tons of potash over 50 years, starting at 215,000 tons a year and eventually hitting 474,000 tons. A representative of Peak Minerals told Offrange that intended purchasers of their potash include specialty crop farmers in California and the Pacific Northwest.

Emerman worries about the company’s consumption of surface water in an arid area, and how that might affect the surrounding ecosystem. The Bureau of Land Management’s own environmental analysis found that the mine would worsen dust pollution in the region and decrease aquifer water levels — although, according to Peak Minerals’s spokesperson, this analysis also showed improved aquifer health, expanded wetlands and riparian habitat, and support of wildlife during mining operations. But groundwater pumping will have “much longer-term impacts far beyond the life of the project,” Larsen countered.

“You’re going to smell it, you’re going to hear it, and in fact, you’re going to see it.”

Larsen is spearheading a lawsuit against BLM for its failure to conduct an updated environmental analysis after the company amended its mining plan in 2025, and for the original environmental analysis it conducted in 2019, which she calls arbitrary, capricious, and in violation of the National Environmental Policy Act.

“I think it’s that attitude of, this has to happen now, it’s got to happen quickly, President Trump says so, so we’re going to do it,” Larsen said. (In an email, a BLM spokesperson said the agency would not comment on litigation matters.)

Peak Minerals claims it will create over 200 jobs during its construction phase and 175 jobs thereafter. Larsen is skeptical. “Milford or Delta would be the [very small] towns that people would be living in if they were gonna go work on this. It’s pretty far from those towns” — over an hour’s drive in each instance — “so I don’t know whether it would have economic appeal for people to pick up and move to these areas,” she said.

Many experts are wondering how to balance what Farm Bureau and related organizations are saying — that we need to boost American potash production to defray costs to producers — with community and environmental needs. Omanjana Goswami, a food and environmental scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, points out that, as a nutrient, “potash has no replacement or alternatives in nature.” But its manufacture comes with enormous environmental costs. Consequently, she’s urging farmers to reduce reliance on potash by “adopting practices that build soil health and improve the ability of soil to sequester nutrients naturally.”

Similarly, CCSI’s Fornabaio advocates for farmers “shifting toward less intensive — and, where possible, regenerative — practices [that bring] multiple benefits, including lowering farmers’ costs for fertilizers and other agrochemicals.” It’s even a concept supported (at least on paper) by one branch of the Farm Bureau, in Iowa.

Emerman’s idea for a different (if unlikely) model involves a collective of farmers that agrees to build a potash mine on their collective land. “We’ll get the benefits, we’ll assume the risks. That would be a utopian idea, okay, but that would be the ideal,” he said.

Because as it stands with these mines, he said, farmers and other community members are being forced to assume all the risks while the companies reap the benefits. “Is it really that simple that potash from a [U.S.] mine is going to supply what a local farmer needs at a cheaper price than he would have got it from Saskatchewan?” Emerman asked, citing the case of the Oak Flat copper mine, which is being fast-tracked to produce copper concentrate destined for export to China. “What’s American about that?”