The Miyawaki method of reforestation inserts small, densely packed wild acreage into urban environs. It’s proving wildly successful.

Route 30 has been carrying vehicles across Pennsylvania for nearly a century. It’s the fastest way to travel east-west across the southern portion of the state, a divided four-lane highway that never stops making noise. For the Horn Farm Center for Agricultural Education in York, the endless roar of cars and trucks speeding past — not to mention the pollution they cough up — had long disrupted an otherwise peaceful site for regenerative farming and community programming.

If only there were a forest to serve as a buffer, the organization’s staff thought. So they planted one.

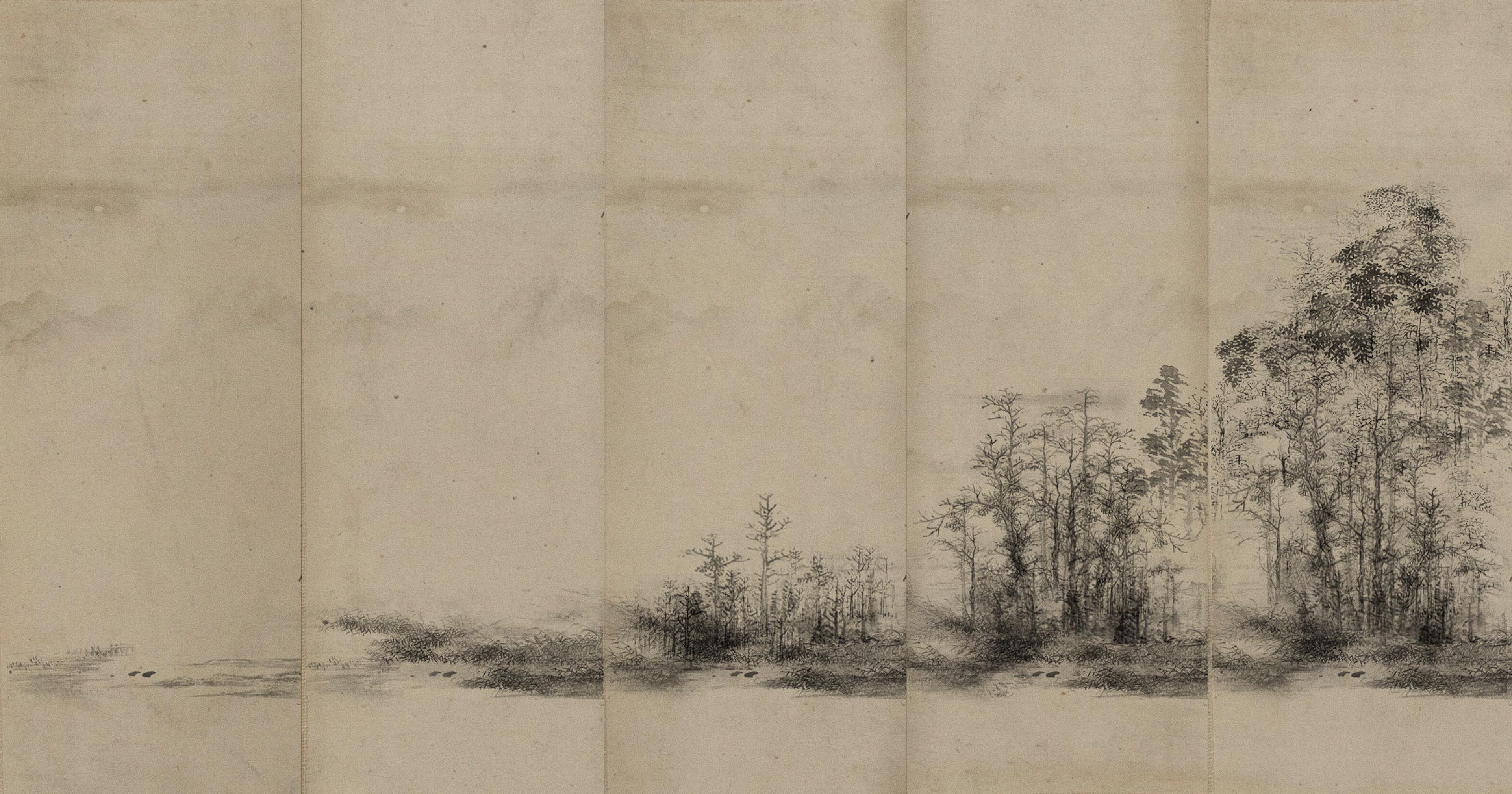

Trees move at their own pace, often taking decades to reach maturity once planted, but Horn Farm didn’t want to wait that long to address its concerns. Instead, it opted to experiment with the Miyawaki method, an approach to reforestation developed by a Japanese botanist. It places a dense, diverse assortment of native species in close proximity to one another in an effort to rapidly regenerate degraded land. Andrew Leahy, the farm’s education and outreach specialist, describes it as “the marriage of competition and collaboration,” a riot of trees fighting for and sharing resources as they grow.

Miyawaki forests — alternately described as micro, tiny, or pocket forests because of their small stature — have been spreading internationally for years. Katherine Pakradouni, a horticulturalist who has planted several in Los Angeles through her landscaping and restoration business, Seed to Landscape, says the movement “has altered the way people think about reforestation.” The method is still building steam in the U.S., where supporters admire it for quickly establishing young forests with myriad environmental benefits and the ability to reconnect people with nature.

In 2019, Horn Farm planted what it believes was the first Miyawaki-style forest in the Eastern U.S. — more than 500 native trees in a 12-foot-wide strip along Route 30. Roughly 100 feet long, it features five major species and 23 supporting species. Six years later, a thriving overstory of oaks, hickories, and sycamores stands nearly 30 feet tall, surrounded by redbuds, dogwoods, and shrubs including elderberry and viburnum. Bluejays and robins nest in the branches, pollinators gather among their host plants, and predators like wasps feed on agricultural pests. On a bright morning in early October, the forest was thick enough to nearly drown out the sights and sounds of the highway just a few paces away. It’s “infinitely eye-catching” for anyone who spends time near it, Leahy says, but more importantly it’s a haven for biodiversity and a boon for soil, air, and water remediation.

Although Miyawaki forests are often found in urban settings, where land is precious and trees are hard to come by, Leahy says they could be a welcome complement for agriculture, particularly on farms with a regenerative bent.

“As opposed to creating systems where we’re farming in a vacuum and then relying on insecticides and chemicals to make it possible to grow things, why not foster the habitat needed by the very predators that naturally keep those things in balance?” he says.

Horn Farm has gone on to apply the method to other sections of its land, including a flood-prone plot that also borders Route 30. With root systems in place, it stopped flooding, instead serving as a sponge that absorbs water during storms. The forest helps prevent run-off and soil erosion, while supporting the farm’s effort to rehabilitate a nearby stream that feeds the Susquehanna River. To make way for its young forests, Horn Farm first decompacted and aerated soil that had been used for conventional agriculture for decades, then planted its seedlings and gave them a heavy mulching, including inches of leaf litter gathered by the surrounding township.

He describes it as “the marriage of competition and collaboration,” a riot of trees fighting for and sharing resources as they grow.

“It’s a cool thing to say we took all the leaves from the community and built a forest with them,” Leahy says.

Reforestation is a global undertaking, backed by a vast assortment of governments, nonprofits, and private companies seeking to address habitat loss and respond to climate change. There’s no shortage of opportunity: 482 million acres globally could support reforestation, according to a recent study by The Nature Conservancy. U.S. nurseries produce 1.3 billion trees annually, enough to plant around 2.5 million acres. For its part, the Forest Service reforests about 190,000 acres annually, partly by planting trees and partly through projects that support the natural regeneration of forests. In traditional reforestation efforts, seedlings are planted some 10 to 12 feet apart to allow each one to thrive. The Miyawaki method applies a much different approach to a much different context.

Akira Miyawaki developed his namesake reforestation technique in the 1970s, inspired by the small protected forests of indigenous trees that surround Shinto shrines and the need for Japan to address the mounting threat of industrial pollution. The method was organized around the concept of “potential natural vegetation” — the overstory, understory, shrubs, and herbaceous species that would occupy a given piece of land if not for human intervention.

Facing the rapid rise of environmental degradation, he also emphasized urgency. His method — simple as it may be — was to identify the species that might once have populated a swath of land, prepare the soil to support their addition, and plant densely so competition for light, water, and nutrients can encourage growth. Some trees won’t make it, but “death is built into the system,” Leahy says. When a tree falls, it feeds the growth of its neighbors.

Miyawaki honed his technique on the campuses of corporations like Nippon Steel and Honda Motor, eventually planting more than 30 million trees across 1,500 sites and winning the Blue Planet Prize — the environmental equivalent of the Nobel Prize. When he spoke at the Toyota plant in India in 2009, he inspired the industrial engineer Shubhendu Sharma to found Afforestt, a for-profit social enterprise that has honed Miyawaki’s principles with a manufacturer’s eye for efficiency. The company has planted well over 100 tiny forests in at least 10 countries, carrying Miyawaki’s method around the world.

“If you see truth in a very simple language, it gets inside your heart,” says Gaurav Gurjar, a jungle tree expert at Afforestt. “And that has happened. People have connected with this method.”

It can be hard to convince grant funders and conservationists that such small-scale restoration is worth supporting when acreage is often the currency of the realm.

The most challenging part of growing a Miyawaki forest is reading the landscape, Gurjar says, in part because most of the world has been so deforested that finding pristine land to mimic is rarely possible. The world has lost over one-third of its forests and half of that loss has come in the last century; an additional 25 million acres are estimated to be cut down each year. Micro forests can’t make up for all that loss, but they can still serve an important role.

“It gives people hope and it empowers them,” Gurjar says.

In Los Angeles, Pakradouni’s experiments with Miyawaki-style planting began with a 1,000-square foot forest in Griffith Park in 2021 and expanded with the development of a 10,000-square foot forest in Ascot Hills Park — about one-sixth the size of a football field — that features 850 native plants sourced from local nonprofits. She sees micro forests as an opportunity for ecological reconnection.

“The world is way bigger than the concrete and the cars and the bills and the news,” Pakradouni says. “There’s something much more essential and close to our souls — that is, the natural world. We can uncover that and be exposed to it and experience it in lots of places we didn’t think we could before.”

Demian Willette, an applied ecologist at Loyola Marymount University, has been studying the Ascot Hills forest, using a neighboring plot as a control and tracking changes based on environmental DNA, remote sensing, and hands-on measurement. The plant survival rate is 89 percent — well above the standard on park land, he says — and in less than two years the forest is already home to 51 percent more biodiversity than its counterpart.

“Biodiversity begets biodiversity,” he says. The forest has also sequestered roughly one ton of carbon dioxide, allowing Willette to project that in 20 years’ time it will be trapping 55 tons annually — not the primary purpose of the Miyawaki method, but a significant climate benefit nonetheless. Leahy suggests micro forests could help farms offset carbon-intensive aspects of their work.

For Willette, Miyawaki-style forests can bring the unwieldy work of biodiversity restoration and climate resilience down to an approachable scale. By gathering communities together for planting and creating unexpected opportunities to engage with nature, they can serve as “a gateway to environmental thinking,” he says. And as his research is showing, their rapid emergence can lead to rapid results.

“It’s actually working,” Willette says. “It’s real and it’s worth the effort. It’s not just hopes and dreams.”

“It’s actually working. It’s real and it’s worth the effort. It’s not just hopes and dreams.”

The accelerated growth rate of a Miyawaki-style forest resembles what sometimes occurs following an avalanche or a forest fire, says Ethan Bryson, the founder of Natural Urban Forests, an Afforestt partner that has planted dozens of forests, beginning in the Pacific Northwest and expanding as far as New Zealand. He likens the forests to “urban acupuncture.”

The costs involved can be significant. An average micro forest typically runs around $25,000, Bryson says, while the Ascot Hills forest cost $35,000. Because juvenile trees aren’t planted in the shelter tubes often used for protection against hungry animals in a tree’s early years, adequate fencing is an important — and costly — consideration for getting a forest to take root in an agricultural setting, Leahy says.

And as he notes, it can be hard to convince grant funders and conservationists that such small-scale restoration is worth supporting when acreage is often the currency of the realm. Micro forests are so densely planted that there’s hardly any space for humans among them, which can deter supporters in urban settings who want to keep park space available for public use, Pakradouni says. Although the Miyawaki method is catching on in the Western world, it still represents a niche within reforestation and ecosystem restoration whose effectiveness will take time to prove out.

But evidence is growing, including research from the UK that found Miyawaki plots had a 79 percent survival rate, even through drought, compared with control plots that averaged 47 percent. Growth rates, too, far outpaced control plots. And despite the higher upfront costs tied to planting densely, the cost per surviving tree ended up lower in Miyawaki plots than in those planted conventionally. Given the range of environmental concerns trees can help ameliorate, the Miyawaki method is “an exciting tool for addressing a lot of the urgent challenges we’re facing,” Bryson says.

Those environmental attributes can make the Miyawaki method an asset for farms, where it can help rebuild soil health, protect crops, and serve as part of a broader water management system, perhaps in the form of a riparian buffer, Leahy says. More than anything, though, he sees it as a reminder that reforestation and restoration can be engaging work, rather than something done from a distance to revive degraded land.

“It restores our sense of being woven into the ecosystem and being active practitioners in the ecosystem. Restoration isn’t about removing ourselves,” Leahy says, “but actually about bringing ourselves back.”