To repopulate land with specialized native flora, it’s not as easy as visiting the seed store.

Dina Brewster’s journey to the seed shortage started with the bug shortage. The Connecticut farmer learned that her blueberries and tomatoes were gradually becoming less juicy due to the shortage of pollinator visits. And the pollinators weren’t visiting as often because of the shortage of native plants in her area. So Brewster went hunting for native seeds, and made an unpleasant discovery.

“I said, ‘Great, we’re going to restore our native plants to our farms and to our neighborhoods and we’re going to save all these bugs,’” said Brewster. “So I went to [a local expert] and said I needed native plants for this region. She said, ‘I’m so sorry, no one is making them.’ I was like, ‘There’s no plants!’”

Across the country, there are hundreds of small and large-scale ecological restoration projects underway, attempts to undo the damage of climate disasters, pollution, and unchecked human development. The goals are varied: supporting pollinators, preventing species loss, shoring up against the effects of climate change. But securing seeds for the plants that are native to particular regions — that have adapted to local soils and climate conditions over many years — has become a surprisingly challenging hurdle to overcome.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine released a report this year, detailing the urgency of building a native seed supply chain. “As the vulnerabilities of humans, wildlife, and critical ecosystem services … grow, the need for ecological restoration in the 21st century will continue its trajectory toward an unmatched scale,” the report reads. “In the United States just as elsewhere in the world, a limited supply of native seeds and other native plant materials is a widely acknowledged barrier to fulfilling our most critical restoration needs.”

Not Just Any Plants Will Do

It’s probably no surprise that many of our native ecosystems are ailing, battered by centuries of human disruption, exacerbated by ever-increasing climate disasters like wildfires and flooding. In recent years, a broad cross-section of government agencies, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations have recognized that ecological restoration needs to be one of our foremost priorities.

For instance, in parts of the West, as wildfires continue to ravage our open lands, a vicious cycle is in place: The fires return each year, burning off local flora which is replaced by non-native grasses. This leads to increasingly big and intense burns; an entire ecosystem is at risk. “The increasing magnitude and frequency of such climactic mega-disturbances is straining not only our economy but the recovery capacity of ecosystems, in synergy with other unceasing stresses including invasive species, energy and mineral extraction, urbanization, and land conversion,” reads the recent report.

Rebuilding an ecosystem can look very different depending on what part of the country you’re operating in and what type of damage you’re trying to undo. Restoring marshlands in the Southeast has a very different flavor from tending to degraded Midwestern prairie landscapes. But there’s a common thread to much of the work: the need for more native plants, essential building blocks to rebuilding healthy ecosystems.

“We believe we’re [at] the beginning of a kind of exponential growth curve, in terms of [native plant] needs,” said Susan Harrison, lead author on the National Academies report and chair of the Environmental Science and Policy department at the University of California, Davis. “Climate-driven events get more and more frequent, more and more severe. We’re already in a place of not having enough [native seeds] to do proper restoration, and it’s very possible to imagine that situation really getting out of hand.”

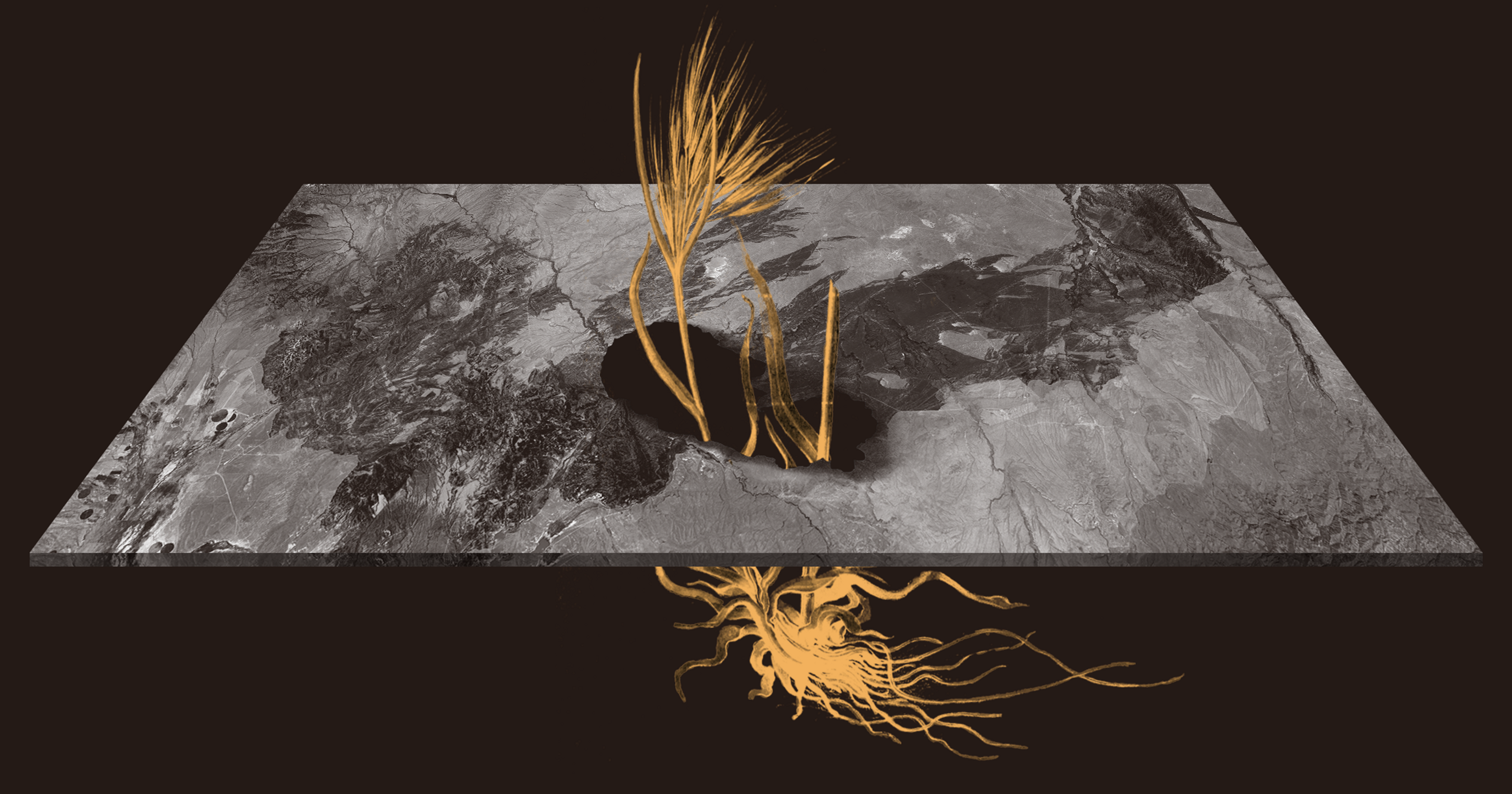

Greenbelt Native Plant Center | Photographed by Samantha Bachert (via Instagram)

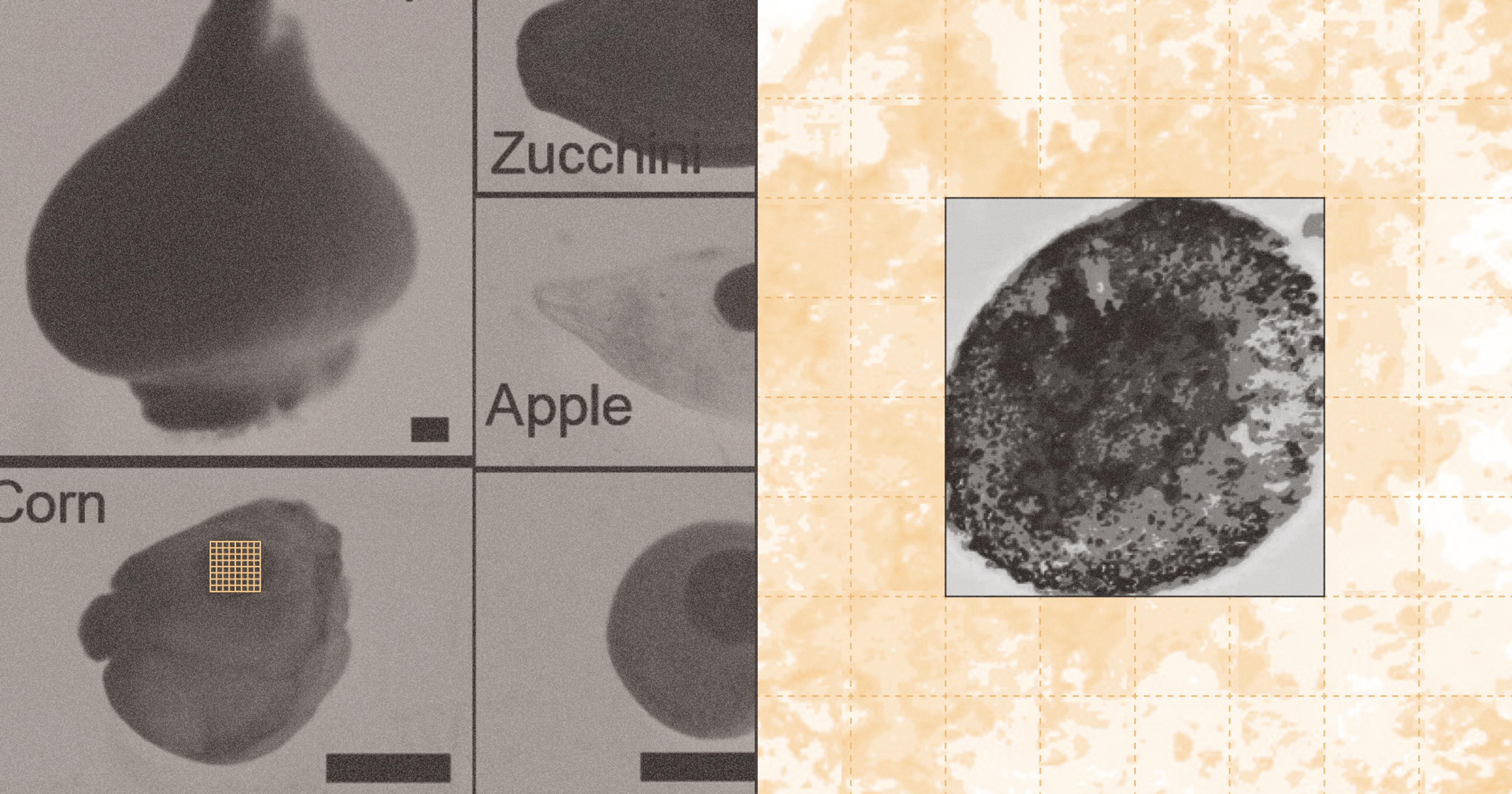

The shortage does not have one simple root cause; supply chain issues abound. For instance, many of the hyper-local plants needed for these restoration projects are not available from commercial seed breeders. Say you’re looking for a specific type of bunchgrass for a California restoration project that requires securing some wild seeds, then investing the resources and time to produce many more of those seeds in a controlled environment. Considering how localized and relatively small these projects can be, they may not seem like a sensible investment for seed companies to make.

This can force ecologists into difficult situations, where they end up using a plant that’s similar to what they need for a restoration project, but ends up unable to thrive in a particular environment — or worse.

John Campanelli, a Ph.D. student in plant science and landscape architecture at the University of Connecticut, has been working to restore native plants growing alongside New England highways. He noted that using seed ecotypes from outside the area that aren’t adapted to, say, local soil pH levels, not only can lead them not to thrive, but they may then cross-pollinate with existing native communities and genetically weaken local plant populations. “Not only might these plants not persist, they could end up weakening the plants that are already there,” Campanelli said.

Even more concerning, sometimes a non-native plant can end up acting invasively, choking out local fauna and ultimately requiring further restoration to reverse the damage it’s done. “Anything that’s a cultivar or not native to an area is kind of an untested experiment,” Harrison said. “There are times when things really go wrong, and a cultivar might not function so well or might even function too well, at the expense of other species.”

Building a Supply Chain

There may not be an adequate supply of many native seeds, but there is certainly a demand. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM)’s massive restoration efforts in the West have made it one of the largest purchasers of seeds in the Western Hemisphere.

“It’s kind of a staggering statistic,” said Elizabeth Leger, Foundation Professor in the Department of Biology at University of Nevada, Reno. She was surprised — in a positive way — to find out just how large the native seed demand is for restoration projects.

Keeping up with the demands of government restoration efforts is easier said than done, however. Harrison said it is typical for agencies to work on funding cycles that are too short to mesh with the needs of seed production. They’ll put in a bid for mass quantities of seeds for a project, but are unable to do so with adequate lead time for seed breeders and growers to produce the product.

“With a few policy changes they could … get this virtuous cycle going that benefits growers and makes these projects successful,” she said — a tactic already occurring when the government collaborates with businesses. “If BLM and other agencies are able to shift … toward a more proactive model of restoration, giving growers the necessary lead time of several years, it could allow them to expand their operations to fill a need that is very clearly out there.”

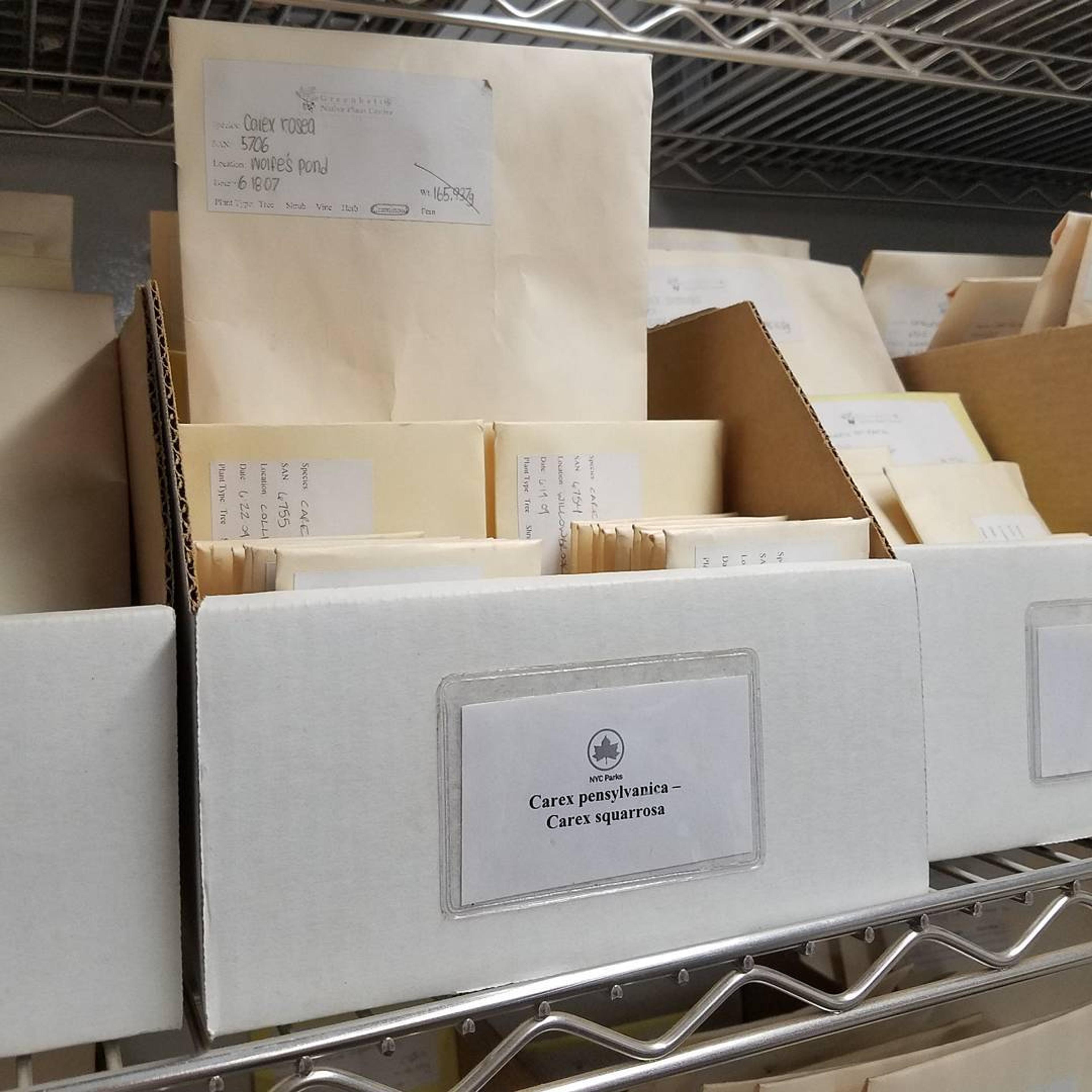

Left: Greenbelt Native Plant Center | Photographed by Nikita (via Instagram) · Right: Native seeds - collected and cleaned, sorted and stored | Photographed by Jim Russell (via Instagram)

To help fill in the gaps of native seed availability, an ad-hoc network of public and private initiatives has been growing across the country. Take Ed Toth, director of the nonprofit Mid-Atlantic Regional Seed Bank (MARSB). Toth is a now-retired 36-year veteran of the New York City Parks Department. Years ago, Toth struggled to find local flora to populate restoration projects in NYC’s parks and other green spaces. This led to the creation of the successful Greenbelt Native Plant Center, a 13-acre greenhouse, nursery, and seed complex on a former Staten Island farm, committed to providing all the seeds and plants necessary for city restoration projects.

Toth notes that replicating such wide-scale solutions to the national native seed shortage would require a total overhaul of business as usual. “I think the challenge is that it’s rather ad hoc and incomplete,” he said, noting that while many efforts are often “well-intentioned, and often very innovative and dedicated,” they simple aren’t comprehensive enough.

“You can’t address [just] one part of the supply chain if there are roadblocks with other parts of the supply chain that stymie the whole effort,” he said. “So the challenge is to develop the supply chain in its totality.”

Brewster, the Connecticut vegetable farmer, took it upon herself to start a small seed company on her property. Named Eco59, the “farmer-led seed collective” is focused on producing seeds to help in Northeastern restoration projects. It’s a private enterprise, but still has the feel of a small-scale, mission-driven grassroots operation.

“So we are growing seeds from this region. Everybody then sends the seeds back to me,” she said. “I am very quickly learning how to clean and test all of the seeds for strength … Then that seed either goes out to homeowners in cute little packets or it goes to nursery growers who want to create a supply chain of plant material for the Northeast.”

Make it Holistic

Eve Allen is program director at the Ecological Health Network, a nonprofit working at the intersection of ecosystem restoration and human health and wellbeing. Her work is focused on “reinforcing and building network connections among private, public, and non-profit stakeholders to help strengthen the U.S. Northeast’s native seed and plant supply chain,” according to the organization’s website. Allen’s work is precisely what Toth suggested — figuring out how to wrangle all the convoluted, ad hoc native seed supply chains into a cohesive whole. It’s complicated work.

“We need to develop all of the key steps of the supply chain simultaneously,” she said. Allen said 28 partners and members of the newly formed Northeast Seed Network recently collaborated to generate an initial list of native plant species that should be prioritized for seed collection, storage, and, ultimately, production in the region. “This process of generating consensus required the input of individuals who are engaged in every step of the supply chain, including botanists, ecologists, farmers, nursery professionals, landscape managers, and restoration practitioners.”

Seed harvesting time at the Greenbelt Native Plant Center | Photographed by Desi Alexis (via Instagram)

Allen has her work cut out for her, but is hopeful a network-based, holistic approach can pay dividends for the future. “It is important to avoid oversimplifying seed and plant material supply chains as circular or linear systems. We assume that supply and end-use of seed and plant material are two sequential steps in the chain. Rather, seed supply chains are complex social networks. Yes, we need to focus on developing more bulk seed and containerized plants. Even more importantly, we need to figure out how to fix asynchronous supply and demand,” Allen explained. That last part refers to the frequent mismatch between restorationists in need of seeds for one specific project and “producers of native seed who want to grow at a large scale and distribute their products to as many markets as possible.”

Despite the challenges, Harrison is hopeful that a streamlined native seed supply chain is an achievable goal — her committee’s National Academies report was intended as a roadmap for possible ways to get there. Harrison’s hope is for some federal intervention that makes it easier for the commercial seed industry to adapt the market to the needs of restoration projects.

“I keep saying this, that there could be a lot of capacity out there to supply a product that there’d be a lot of potential demand for that product, but you need a little bit of intervention in the market, which is usually by large federal buyers,” she said. “If society decides that it’s something that they want, whether it’s solar panels or electric cars, you can probably take this all the way back to the Industrial Revolution. A little bit of the federal government using its massive power to be a better customer for that product and to give a little bit of technical help and infrastructure help to the private sector to produce it. And then you can have this flourishing private sector that benefits everybody because business makes money off of it and the public gets, in this case, better restoration on our public lands.”