A grassroots movement has emerged, promoting pollinator-friendly yard design and public awareness to help fortify a sustainable food system.

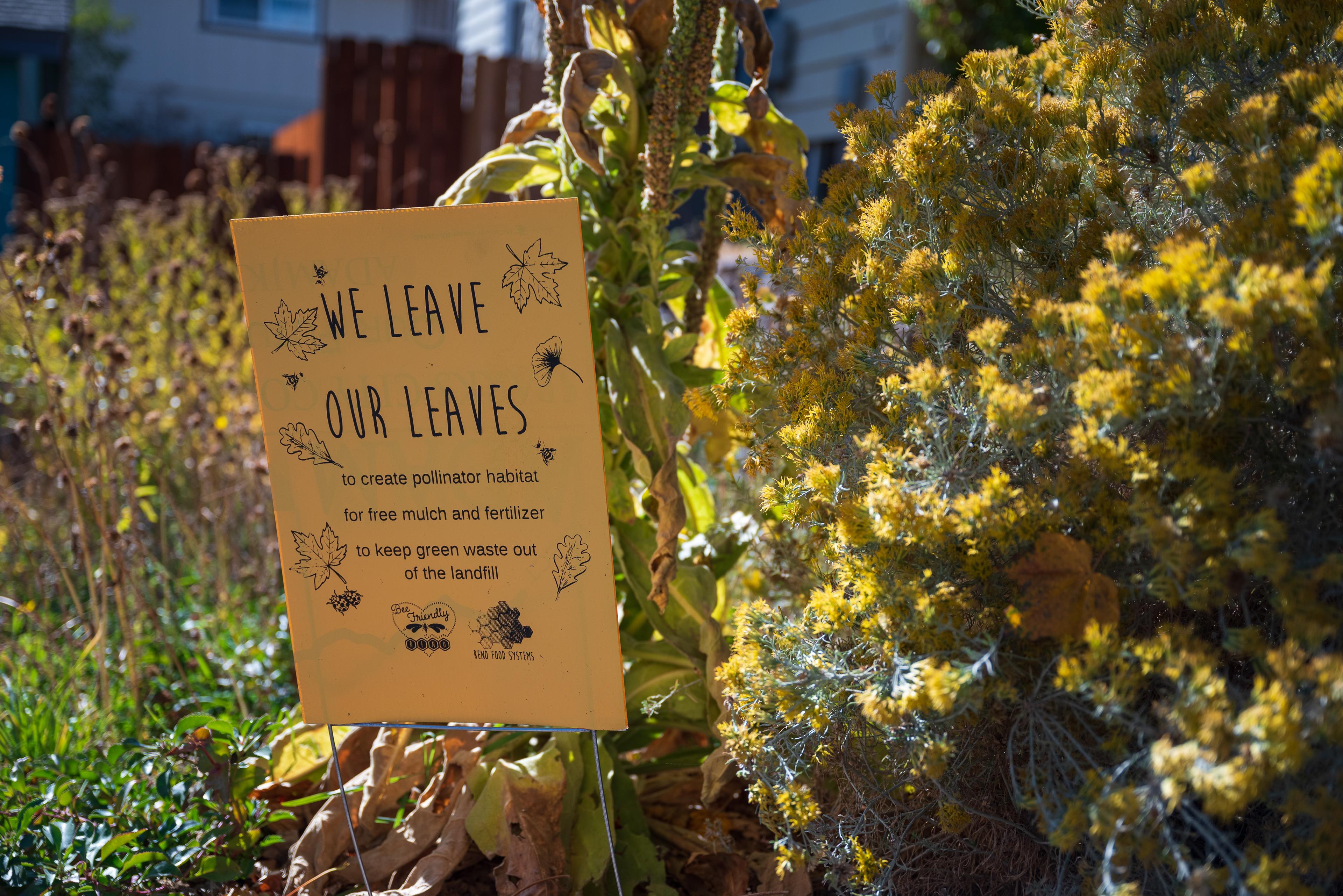

What once was a typical American lawn now hosts a myriad of native plants. Flowers bloom from the early spring through the first fall snow. Climbing up from a bed of wood chips are tall, top-heavy stalks of lavender and bright spears of rabbitbrush. Leaves and underbrush squeeze themselves into the empty spaces between flowers. You may not notice at first, but there are two yard signs tucked in among the overflowing plants. These particular placards are not advocating for a political candidate — they’re for bugs. The signs are the forward-facing symbol of a national grassroots movement that is making moves to protect pollinators.

One in three bites we eat is made possible by pollinators. By seeking the nectar of flowering plants, insects move pollen from flower to flower. This then leads to the fruiting of virtually every fruit and vegetable we consume. From butterflies to bees to moths, they play a pivotal role in our natural ecosystem and our food supply. However, as you’ve likely heard, pollinator populations are declining — and fast.

Community organizers are now working across the nation to weave together a safety net for pollinators, a net that employs many levels of action. First order of business: promoting the conversion of lawns to pollinator-friendly native flowers and shrubs. There are also now food labeling certifications for farms that abide by a set of protective rules. Groups have devised citizen pledges encouraging people to commit to protecting pollinators. And there is a nationwide push to establish bee-friendly cities. Through a national certification program, any city can take steps to recognize, support, and encourage pollinator conservation. All of these projects have their sights on building a robust network of pollinator-friendly habitats across the country. The motive is clear: Pollinators help produce more produce, ultimately benefiting farmers and eaters alike.

“A lot of people have this prejudice that people who let their dandelions grow are lower class,” said Melissa Gilbert, founder of the Nevada nonprofit Bee Friendly NV. Based out of an urban vegetable farm in Reno, this proactive group of farmers and community members has launched a campaign — one of dozens across the country — to build and defend habitat and inform everyday citizens about the importance of protecting pollinator populations.

Gardeners, homeowners, and renters alike can all take a pledge with Bee Friendly NV that commits them to cultivate habitat for pollinators. One of the first items on this pledge is not weeding out the dandelions, one of the first flowers to bloom each year, and a vital pollinator food source. Nevada is home to a quarter of the nearly 3,600 native bee species in North America. The region is also an important corridor for other pollinators such as monarch butterflies.

“Some of the biggest factors that are leading to these declines are pesticide accumulation, exotic species, and light pollution,” explained University of Nevada, Reno, professor of biology Matthew Forister. His work focuses on the change in insect populations and plant-insect ecology (while his academic profile photo shows a butterfly perched on his cheek).

One 2019 survey showed 95% of respondents wanting to help pollinators, but only 34% were confident they knew what to do.

Forister’s research also found a 1-2% decline in butterfly populations each season. Correlated with other studies, Forister said it is safe to assume all pollinators are facing a similar fate. This concerns him because, compounded over 20 years, pollinator populations have declined almost 30%.

By many accounts, people are increasingly aware of the pollinator plight, but largely unaware of what they can do to fix it. One 2019 survey showed 95% of respondents wanting to help pollinators, but only 34% were confident that they knew how to do anything useful.

“Once you put a sign up in your yard that says, I’m standing for the bees, it always makes you more aware of all of your actions,” explained Bree Kasper, one of Bee Friendly NV’s first pledge takers who has been working to establish a pollinator-friendly garden and yard. Kasper is driven by the knowledge that protecting pollinators is a vital step to ensuring our food supply’s long-term sustainability.

One family of commonly used agricultural chemicals has proven particularly harmful to pollinating insects — neonicotinoids, or neonic pesticides. Recent research has also found some fertilizers repel pollinators. Yet a blanket ban on neonic pesticides is not without its downsides. For example, a recent ban in the state of New York has some agriculture experts concerned about the corollary effects of prohibition, and the lack of comparably effective pest control alternatives. Solutions aren’t simple, which is why pollinator advocates are working on many fronts.

“We basically want to meet you where you’re at and help you improve,” said Laura Rost, communications director at Bee City USA, an initiative of the influential Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. This organization is working on expanding the safety net for pollinators across the country by providing a plug-and-play framework for U.S. cities to embrace. They have classified almost 170 cities across 45 states as bee-friendly, with many more to come. To become certified as a Bee City, a community’s governing council must pass a resolution committing to pollinator protection. In practice, the city then has to implement tangible steps to maintain certification.

“The big thing is developing an integrated pest management plan for the city, an idea that is not just about pollinator health through pesticide reduction,” said Rost. Beyond reducing reliance on pesticides, cities and communities must work to increase low-fi initiatives like manual weed pulling and pollinator-friendly habitat creation. Together with grassroots groups, Rost said communities have “the tools to actually make these changes,” emphasizing that this is a pragmatic movement, focused on actual, realistic solutions.

“We don’t need perfect roses, we need functioning ecosystems.”

Another Xerces initiative is Bee Better Certification for farmers, which evaluates whether a given farm meets certain criteria like maintaining pollinator habitat on at least 5% of its acreage and developing a pest control program that is less pesticide-intensive. Compliant farmers get to use a Bee Better seal on their food labels. Currently 20,000 acres of farmland have been certified nationwide.

To prevent a collapse of our food systems, pollinators “need protected nesting sites, and they need protection from pesticides,” said Rost. Effectively, they need more habitat. And through a multifaceted approach that focuses on increasing proper weed management and community education, Bee City-certified communities are establishing a nationwide network of pollinator habitats.

For her part, Kasper has printed out detailed flyers and knocked on doors to educate her neighborhood further. “The campaign … is just bringing awareness to your neighbors and having a really good conversation with the people around you,” said Kasper. “Don’t give me credit; give the pollinators credit.”

Forister believes a big part of the challenge is shifting our national mindset away from the idea of perfect horticulture. “We don’t need perfect roses, we need functioning ecosystems,” he explained.

Forister would love to see more widespread dissemination of vital pollinator information. For instance, some of his more recent research has found nurseries across the country selling milkweed seedlings — a vital plant to butterflies — contaminated with dozens of pesticides. Many of the plants were labeled as pollinator-friendly.

After learning about Forister’s research, Gilbert was stunned. “We’re trying to launch a bee-friendly certification for our nurseries,” she explained, adding that the program’s aim will point people towards uncontaminated seeds and seedlings. Gilbert believes that sharing relevant, useful information as broadly as possible is a key plank in the pollinator advocacy agenda.

Another key component of every pollinator campaign is to spread the word about habitat loss. Bree Kasper relies on the accurate, research-based information from Bee Friendly NV and the Xerces Society, when she takes it to the streets. A veteran canvasser, she prints out Xerces flyers and takes them door-to-door.

For Kasper, it is about much more than having a beautiful yard. The flowers blooming almost year-round on her property become a statement, a message affirming that she believes in the protection of pollinators. “This is something that everyone can support,” she explained. “We should be doing things like creating events, creating momentum, and getting the information out there.”