Companies plan to sink agricultural waste to oxygen-free parts of the ocean. What could go wrong?

200 miles off the coast of New Orleans, and 2,200 meters below the surface, there’s a dip in the ocean floor containing a brine that makes the surrounding seawater look positively sweet. Sipping from a Jurassic-era salt deposit — with 500,000 metric tons of salt dissolved into the water every year — the Orca basin brine pool is roughly eight times saltier than ocean water. Though it’s dense with microbes, the basin is devoid of oxygen and toxic to aquatic animals.

But the same traits that make it hostile to life have a company eyeing it as a tool for maintaining a livable climate.

In May, a company called Carboniferous applied for a research permit from the EPA to drop 20 metric tons of sugar cane bagasse — the fibrous material left after crushing stalks to get juice — into the Orca Basin, a process the company says could store carbon for hundreds of years.

“We couldn’t do this in the lab, and there’s insights we’re going to be able to actually get with this plan that are going to justify the effort and the risks,” said Morgan Reed Raven, chief science officer at Carboniferous and assistant professor of earth sciences at UC Santa Barbara. “We’re going to throw everything at this, and if the data really supports it, then it will have definitely been worth it.”

The Carboniferous field trial is just one of a growing number of projects that propose to use oxygen-free (or anoxic) parts of the ocean as disposal sites for agricultural waste, enabling the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere — a removal the IPCC has said is essential to reaching net zero emissions.

Yet some scientists are raising concerns with the safety and effectiveness of these methods — not to mention their potential to distract from emissions reductions — while farmers ask if it’s the best use of the waste material. Either way, projects are moving forward — are we ready?

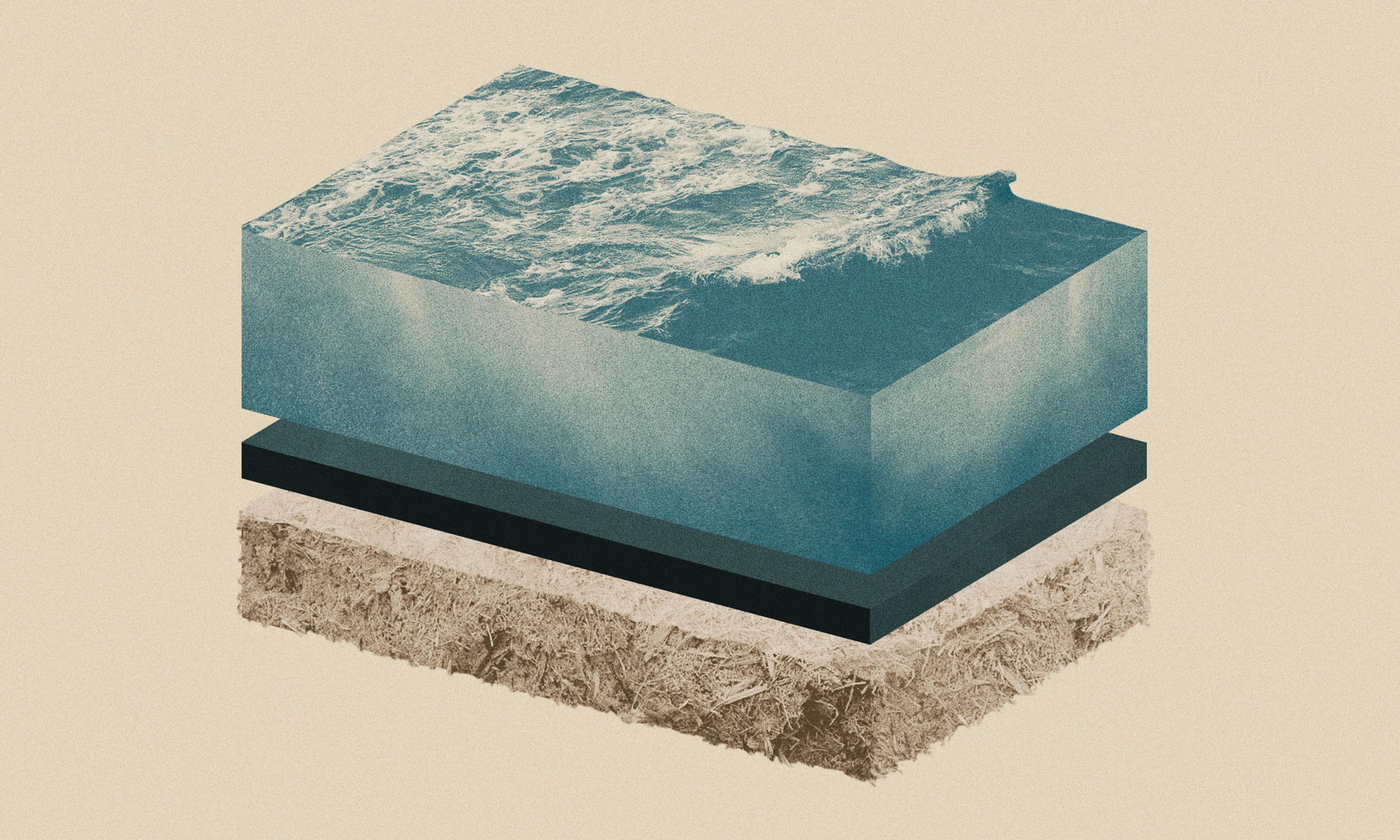

Sinking agricultural waste to the deep sea — or “Marine Anoxic Carbon Storage,” as the company Puro.Earth, which validates carbon removal methods, dubbed it back in April — rests on a simple premise.

As crops photosynthesize, they incorporate carbon into their tissues. After those crops are harvested and processed, whatever is left over is often burned or tilled back into the soil and decomposes, which sends that carbon back into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

By sinking that crop waste into anoxic environments instead, researchers hope that material would potentially resist breaking down for thousands of years, effectively storing the carbon long term.

“We talk about [climate change] as being existential. We should act that way.”

Raven said it’s a promising enough idea that when the co-founders of Carboniferous reached out for advice, she assumed work had already begun. “I said, well, it’s an obvious idea. There must be a dozen teams working on that. And they were like, ‘Would you believe there aren’t?’”

That led to work in the Orca basin — a site Raven said has many advantages.

The basin is clearly defined — it has edges, it’s relatively small (3.2 miles squared), and it’s all within the United States — making monitoring easier. But more importantly, it has no oxygen, meaning no animals to quickly break down organic material and release carbon dioxide (the microbes that do exist there break down organic matter very slowly). As a brine pool, it has the additional advantage of being salty; salt has been used to preserve food for thousands of years, Raven said, and in the Orca Basin, sediment cores have revealed perfectly preserved macroalgae — seaweed that would otherwise turn to slimy goo in days, even in anoxic parts of the ocean. “For it to come up looking pristine is truly remarkable.”

Permanent preservation isn’t typically the goal in waste disposal. But in this case, Carboniferous was happy to learn, in early research trials, that material such as kelp stayed intact after 200 days in the basin. “They’re almost brighter green than when we put them in the brine. It’s just sort of a jaw-dropping gut check just how effective the salt is at preserving stuff,” Raven said.

As a next step, Carboniferous is proposing a field trial that will involve sinking 20 bales of sugar cane bagasse from Louisiana; bagasse is a waste material that requires a lot of energy to manage, often by burning, Raven said. “And so that particular scenario simplifies a lot of the … issues that are going to become really important as we think about scale.”

In the field trial, bales of bagasse will be wrapped in burlap and rope, and sunk to the bottom; researchers plan to test ways to examine whether the material is breaking down, along with other monitoring.

“I said, well, it’s an obvious idea. There must be a dozen teams working on that. And they were like, ‘Would you believe there aren’t?’”

The Orca basin is just one of the anoxic sites being explored for storing crop waste; another, much larger basin is found in the Black Sea, the kidney bean-shaped inland sea bordered by Turkey, Russia, and Eastern Europe.

Many countries in the area are large agricultural producers, producing millions of metric tons of produce, as well as wood products.

A company called Rewind is moving forward with a plan to use this waste — particularly, woody leftovers after pruning fruit trees, and residuals from the timber industry — to sink biomass into the Black Sea, which is largely devoid of oxygen. That provides a huge capacity for carbon storage, said Rewind CEO Ram Amar.

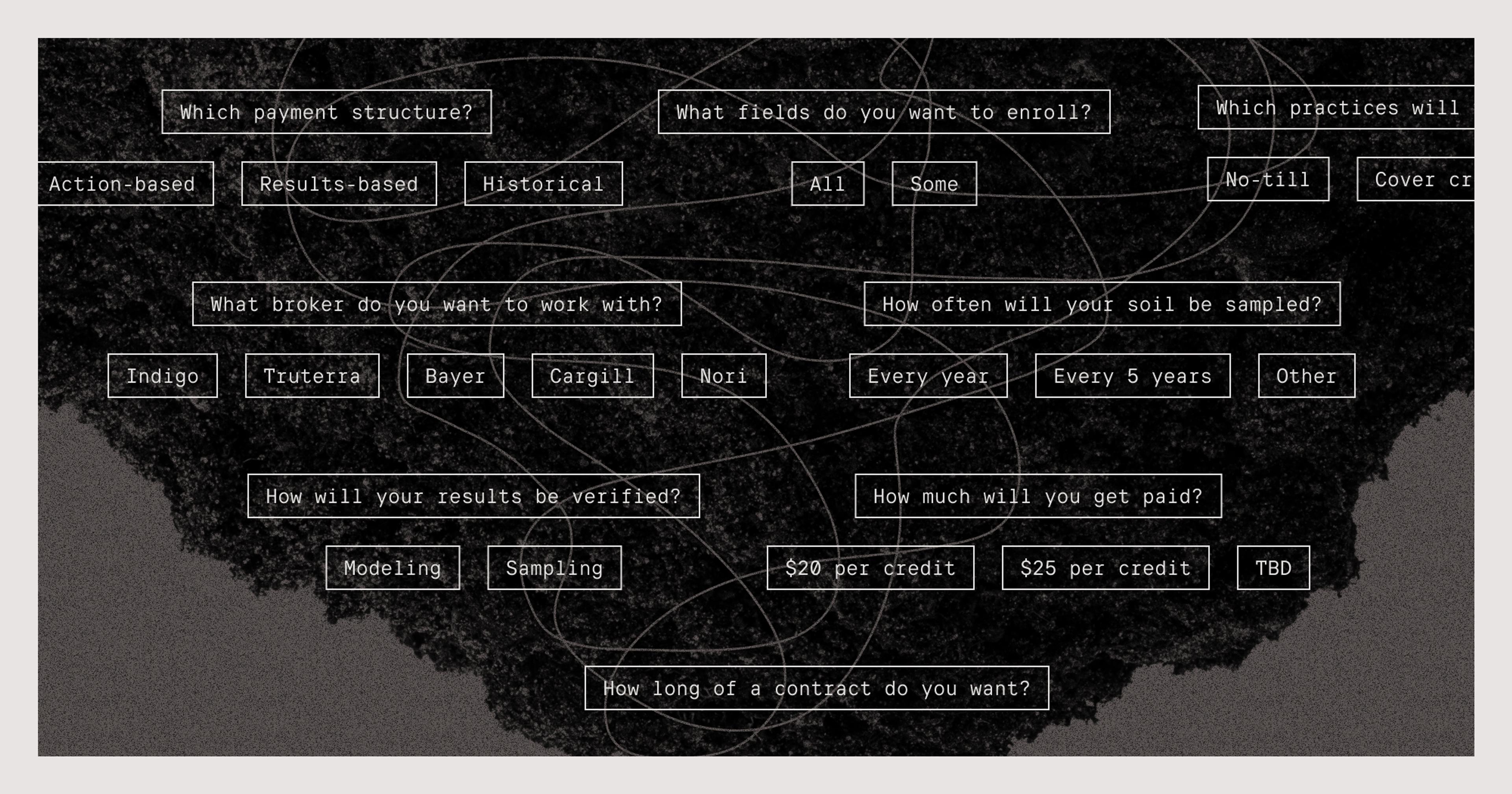

Amar says the company tried various kinds of biomass, from lettuce and corn stover to wood, and concluded wood degraded the least. Rewind is currently working through the permitting process with Romania on a plan to sink 100 metric tonnes of biomass in 600 meters of water.

Amar said there’s an analog for the effectiveness of this method in the wood that can naturally be found in the Black Sea, where shipwrecks from antiquity look as pristine as the day they sank. “You can find wood that has been in these environments for a thousand years or more.”

Altogether, Amar said anoxic basins could provide half a billion metric tons of carbon dioxide removal — a process that he said scientists at a recent Rewind workshop concluded can’t happen quickly enough.

“30 of the world’s leading marine researchers are saying, ‘Why aren’t we moving much, much, much faster with this method, even at very large scales,” he said. “The scale relative to the Black Sea … is really, really, really small, and therefore the environmental risk is really non-existent.”

“These are ecologically really interesting and special areas; using it as a garbage dump doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to me.”

Lisa Levin isn’t so sure.

Levin is a marine ecologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and co-author of a recent paper that touches on biomass sinking. She says at the research level, there likely isn’t any risk. But at a large scale, she worries that filling these unique environments with sugar cane byproducts or other agricultural waste will have negative impacts; she questions whether we know what we’re at risk of losing in these environments, which contain unexplored microbial diversity.

“These are ecologically really interesting and special areas; using it as a garbage dump doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to me.”

Amar said Rewind has dedicated significant resources to understanding the impact, and has concluded the effects of storing biomass would be in line with the natural variability of that environment; in the Orca Basin, Raven said sinking biomass is unlikely to change the ecosystem, since it already has no oxygen (biomass sinking can otherwise deplete oxygen), though she said when thinking about other sites and possible expansions, “we move into much harder questions.”

Levin and other scientists prepared input on Carboniferous’ plan in the Orca Basin, the public comment period for which closed in mid-July; so far, she said her main conclusion is that the approach doesn’t have the capacity to turn down the temperature of the planet. “It’s not going to be able to accommodate enough carbon to affect climate change. So my feeling is this is probably about selling carbon credits and making money.”

For some farmers, there’s also the question of the best use for agricultural waste.

Luke Lasley grows five acres of rare heirloom sugar cane on a farm in southwest Florida, which they press for fresh juice and shelf-stable syrup.

Lasley said the resulting bagasse is highly useful. “It’s actually a resource for the farm if you know how to work with it.”

“Shipping it out into the ocean and trying to sink it down there seems like a crazy way to sequester carbon because there’s a lot of costs involved with getting it there.”

Mostly, Lasley uses the bagasse to make biochar, a carbon-rich material similar to charcoal, made by roasting bagasse at high heat without oxygen. He said this helps retain water and nutrients in sandy soil, in addition to sequestering carbon.

Biochar is useful enough that Lasley buys what he can’t make himself — given that bagasse makes good biochar, he said he found the thought of sinking it into the ocean “kind of a wild idea.”

“Shipping it out into the ocean and trying to sink it down there seems like a crazy way to sequester carbon because there’s a lot of costs involved with getting it there, when the farm that’s producing it basically needs it in biochar form.”

Ultimately, trade-offs are becoming a fact of life in a changing climate, and proponents of carbon removal say the hazards need to be considered against the cost of doing nothing to remove emissions; when it comes to sinking crop waste, scientists say the potential means we have to at least try.

“We talk about this as being existential,” said Raven. “We should act that way.”