Every gallon of bourbon produces 10 gallons of waste called “whole stillage,” traditionally converted into animal feed or spread on farm fields. We need somewhere else to put it.

In 2023, Jim Beam hosted 126,000 visitors at their expanded distillery in Clermont, Kentucky. Their other local distillery, a 15-minute drive away in the town of Boston, isn’t open for public tours, but they’re planning to make dinner for a few billion guests by the end of the year.

The guests are their tiny new neighbors: Bacteria and other microorganisms will live in tanks across the street eating “whole stillage” piped over from the distillery.

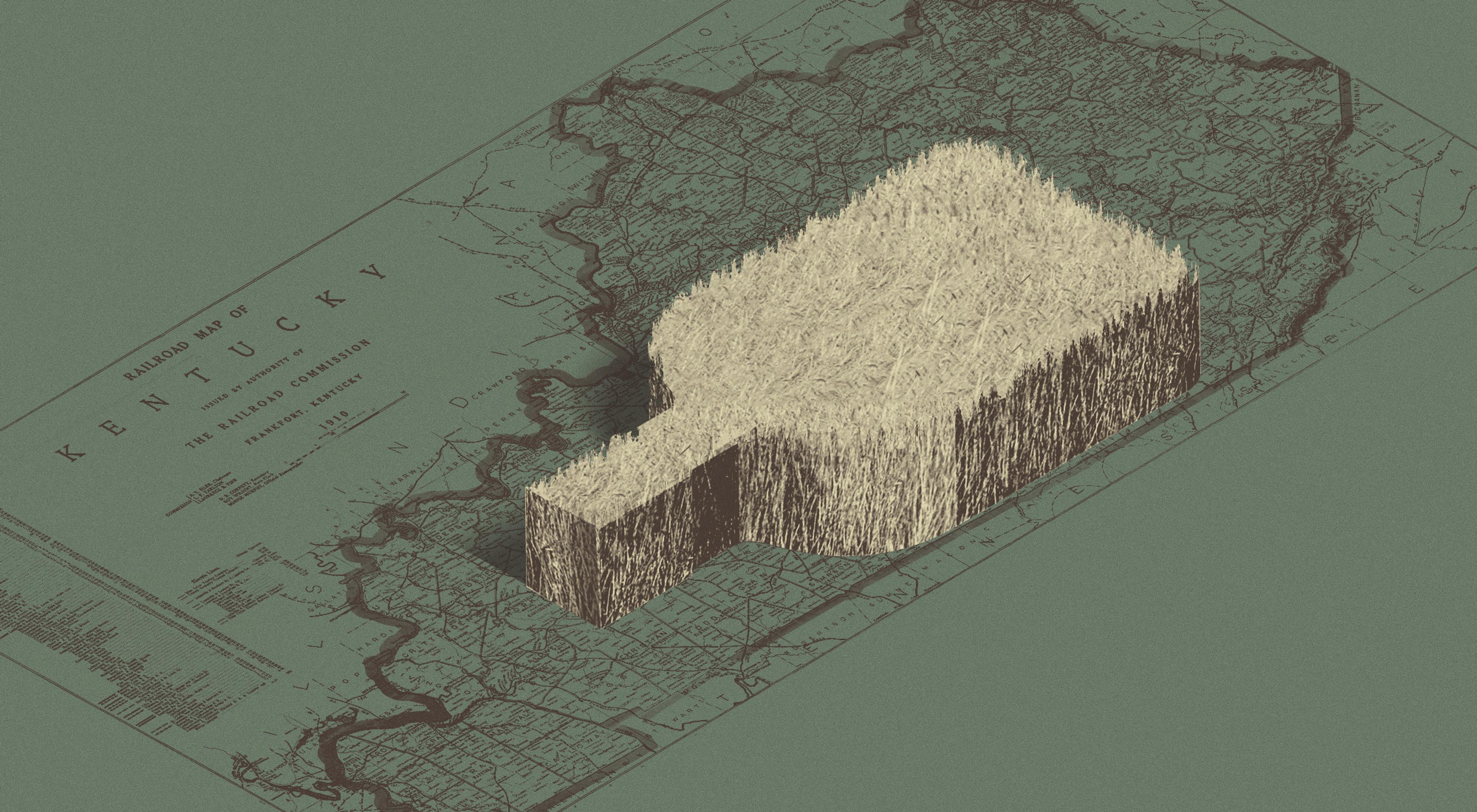

Whole stillage is the watery, cloudy mixture with around 10 percent solids that is left over after corn and other grains are fermented and alcohol is separated out during distillation. For every gallon of bourbon made, around 10 gallons of whole stillage are produced — an estimated one billion gallons annually in Kentucky.

The American whiskey industry has been scaling up over the last decade, and its distillers have been planning for better and more efficient ways to get rid of — and/or profit from — all that stillage. Kentucky Bourbon production increased 475% between 1999 and 2021. In 2022, Jim Beam announced they’d be increasing their distilling capacity at the Boston facility by 50 percent. Buffalo Trace completed a 1.2-billion-dollar, 10-year expansion in early 2025. Heaven Hill, Bulleit, and the other largest producers also greatly increased capacity or built additional distilleries. That’s a lot more whiskey on the market, and a lot more stillage to process.

The tiny critters that will live in tanks next to the Jim Beam distillery are being brought in to help. The stillage will pass from one tank to another in an anaerobic digester system, and then to a huge rectangular covered storage pond. There, the liquid — now with only around two percent solids remaining — can be trucked away for use as liquid fertilizer. Along the way, hungry microbes consume the stillage and release methane gas to be collected from the top of the tanks and pond.

Anaerobic digester systems are used to manage waste in many different industries, but the methane is often flared off — those fire spouts you see driving by industrial sites at night — rather than captured. But Jim Beam’s neighboring facility is owned and operated by 3 Rivers Energy Partners, a renewable energy company whose founders have roots in energy infrastructure.

They’ll transform the methane into “pipeline quality” renewable natural gas (RNG), which will then be sent back across the street to power the distillery. The companies predict that the Beam distillery will be 65% powered by RNG from those microbes in the future. Welcome to the neighborhood.

Cows, Fields, Fish, and Flies

Whole stillage has to be dealt with one way or another — if the tanks that store it fill up, the distillery can’t keep making more whiskey. Smaller producers have reported having to shut down production when snowstorms prevented trucks from hauling it away.

The low-tech way to get rid of stillage is to “land apply” it to fields as fertilizer/compost, or run it into a trough and feed it to cattle. Whole stillage is mostly water and spoils in a few days, so it needs to get to the animals quickly before that happens. In fertilizer use, it should be turned into the soil soon after application.

As the amount of stillage increases with increased whiskey production, the more land and animals are needed. Eventually that becomes an issue. Joseph W. Ward, executive director of the Indiana-based Distillers Technology Council (DTC), says, “There’s only so much land that you could land-apply it. There are only so many people that could take it wet.”

Whole stillage has to be dealt with one way or another — if the tanks that store it fill up, the distillery can’t keep making more whiskey.

The DTC was founded in the 1940s (as the Distillers Feed Research Council) to work on the same problem that whiskey makers are facing today — to “develop uses for their non-fermentable waste materials.”

A solution developed in that post-war era was to evaporate much of the water from whole stillage, and dry out the solids with steam tube dryers — huge, short, thick pipes, through which wet grains pass into one end and come out dry on the other as DDGS, for “distillers dried grain with solubles.”

Evaporating all that water is energy-intensive, and alcoholic beverage producers have made sustainability initiatives a larger part of their marketing. As the whiskey industry was booming earlier this decade, industry leaders finally acknowledged that they too needed to get with the times and come up with better and more forward-looking solutions to the increased quantities of their byproducts.

Bourbon Gets In On It

In 2021, the Distillers Technology Council, along with other industry and economic groups like the James B. Beam Institute for Kentucky Spirits at the University of Kentucky, sponsored a “reverse pitch” competition. Entrepreneurs and engineering firms were invited to submit proposals with winners invited to pitch at a DTC conference ways “to implement their ideas for surplus stillage usage.” The first criteria listed for consideration was that proposals should “prioritize sustainability and environmental impact.”

One submission proposed making high-protein material by feeding spent grains to black soldier fly larvae and red wiggler worms. Another suggested using the grains to produce the low-calorie sweetener xylose, plus activated carbon. One applicant proposed a centralized facility to make high-protein products like dog and fish foods, which could be used by several smaller distillers.

The competition may have helped put some projects into motion, only to encounter recent roadblocks. “Unfortunately, I think they haven’t moved as quickly as their plan was because of what’s happened in the last, you know, eight or nine months,” said DTC’s Ward.

Under the current administration, tariffs and stressed international relations could impact trade in animal feed ingredients, as well as American whiskey, but some big projects are still in the works. Buffalo Trace announced this July a partnership with Meridian Biotech, an entrant from the reverse pitch competition, in which the company would take a direct pipeline of stillage from the distillery and convert it to “multifunctional alternative proteins.”

“We’re ramping up. We have to feed the biology, slowly, and build out the bacteria colonies.”

Meridian’s website lists four products: a yeast product for pet foods, a mixed microbial ingredient for aquaculture feeds, a dietary fiber gel usable in human food, and a high-phosphorus, slow-releasing fertilizer. Construction on the project is set to begin later in 2025.

The RNG projects that produce gas instead of protein products are going ahead as well. Louis Buck, SVP of public affairs for 3 Rivers, said that as of early August, “Jim Beam is receiving stillage now, but very little. We’re ramping up. We have to feed the biology, slowly, and build out the bacteria colonies. So the valve is open — it’s been commissioned.”

A second 3 Rivers facility is being constructed near Jack Daniel’s in Tennessee, which Buck says is “about a month or six weeks behind” the Beam project. The projects look similar on paper, but the RNG from Jim Beam will be used to power the distillery, while the Jack Daniel’s project RNG will be fed into the local pipeline to heat houses and the like.

These RNG facilities rely on a constant supply of stillage to feed the microbes, which is why they’re not often suitable for small distilleries — or ones that may close during flagging markets like the one the American whiskey industry is suddenly facing.

Enough of a Good Thing?

All that quick growth may have resulted in a whiskey glut. In 2025, several high-profile new American whiskey distilleries have closed, and other major brands have reported a decrease in sales. In late September, The Spirits Business reported that global liquor giant Diageo was pausing distilling operations at its Balcones distillery in Waco, Texas, through June of 2026, and pausing distillation at their George Dickel distillery in Tennessee “through this fiscal.”

Even the huge new carbon-neutral distillery in Lebanon, Kentucky, built to produce Bulleit bourbon, paused production earlier this year. The company has an existing distillery in Shelbyville in which to keep making Bulleit, but had they installed anaerobic digesters on-site they would have had to make alternate plans.

But for the big American companies still actively making whiskey, these new facilities could be proof of concept for the distillery-RNG facility partnership that is common in Scotland. Buck of 3 Rivers noted, “Although the forecasts are down for our two partners, their corporates have other brands nearby.”

One of those brands is Maker’s Mark, owned by Suntory Global Spirits, the parent company of Jim Beam. Maker’s gave AD digesters a try in 2008 to produce “methane-rich biogas,” but Buck said that Maker’s does not currently have a functional anaerobic digester on site. “They’re fully exploring, including with us, if they want another one. So, we’re optimistic. We look good. We’re gonna make our money. We’re gonna be profitable,” he said.

There’s a current sales hiccup for sure, but there will always be more American whiskey being made, and a need for energy sources. Starting with the biggest distilleries may be the way to go.

Buck said, “We’re not going out of business, and neither is Jim or Jack.”