Though the $70 billion palm oil industry has made real progress in reducing deforestation, biotech companies are trying to brew up synthetic alternatives.

If you eat peanut butter, wash your hair, or brush your teeth, you’re most likely a palm oil consumer. For food and personal care companies, its versatility and low cost makes it a wonder ingredient.

Palm oil is present in 50% of packaged goods, from crackers to chocolate to detergent to skin cream: It can be used to enhance spreadability, as an emulsifier, a moisturizer, or to provide a pleasant texture. Palm oil is the world’s most prolific oil crop per acre — but it also has deforestation and labor exploitation baggage that has severely damaged its global reputation. It only grows in sensitive tropical climates near the equator, leading to heavy deforestation in the 1990s that accelerated during the aughts.

In the bad old days of 2012, over 850 square miles of forest was bulldozed and burnt in Indonesia alone (that’s an area one and a half times the size of Los Angeles). The resulting plunge in populations among endangered orangutans and pygmy elephants became a flashpoint for global outrage, prompting consumer boycotts. The industry reacted by founding the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), which certifies products as having been produced without destroying rainforests or exploiting laborers. Deforestation in Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer, is just 18% of its all-time highs, though it is ticking up slightly.

With palm oil prices per ton having doubled from about $500 to over $1,000 since 2019, the question is whether the improved palm oil industry will lean into sustainability and avoid another frenzy of deforestation — or if the product can be replaced by something else entirely. On the alternative side, a handful of companies around the world have focused on creating oil alternatives using advanced biochemistry. The most common technique is called precision fermentation, in which scientists feed sugar or another feedstock to specialized microbes, which then ferment it into oil. The process resembles making beer.

With high palm oil prices creating large financial incentives to ignore deforestation guidelines, these biotech companies see an opening — by starting with the higher-end market for specialty oils in food and cosmetics. Established palm oil analysts scoff that the tiny volumes produced in the lab will be able to scale up and compete with the 72 million tons of conventionally grown palm oil brought to market each year. They say that makers of biochemical replacements for palm oil underestimate the enormous economies of scale built into the price of every ton produced.

“Maybe one day in the not too distant future, these technologies will play a role in the replacement for the palm oil industry,” said Jack Ellis, an independent consultant based in Vancouver who has written about agriculture and green technology. “But at the moment, it’s still very early, and it’s not clear how they get to the scale of this huge palm oil industry that we already have.”

The Alternatives

Lars Langhout is the CEO of a Dutch company called NoPalm Ingredients that ferments agricultural waste into an oil that can be used in food or cosmetics production. His stated goal is not to replace the 73 million-ton giant that is the palm oil industry, but to halt additional growth that would cause more deforestation.

“The ‘dragon’ we are slaying is not the existing volume, it is the growth,” he said. “Palm oil demand is increasing by roughly 4% per year, which adds 3 million tons of demand. Today, there is no sustainable strategy to supply this growth. Indeed, only 20% is even certified sustainable. This drives deforestation and biodiversity loss as well as price volatility and long-term supply risk for our customers.”

Bryan Quoc Le, a food scientist and author of 150 Food Science Questions Answered, noted that most large palm oil producers depend on cheap labor, which will make it hard for biochemistry alternatives like Langhout’s to compete. A recent study found that the minimum wage in Jambi province, on the palm oil powerhouse island of Sumatra, was about $200 per month. Even so, 59% of workers in the province reported making even less than minimum wage. “I think [synthetic oil producers] will have to switch to more lucrative industries, like cosmetics or skincare,” Le said. “The food industry does not provide nearly enough returns where a high-grade palm oil is worth producing.”

“The food industry does not provide nearly enough returns where a high-grade palm oil is worth producing.”

Shara Ticku is the CEO of C16 Biosciences, an NYC-based biochemistry company doing just that. Ticku says that six different cosmetics brands have launched this year using her company’s “torula oil” product, a palm oil replacement made when torula yeast ferments sugar. That includes the recent announcement of an Estee Lauder-owned brand called NIOD that uses torula oil to make a skin cleanser.

Ticku notes that food companies typically have razor-thin gross profit margins, whereas cosmetics brands have margins of 50% or higher. That gives them more financial wiggle room to try a new, ecologically friendly ingredient. And it’s not just a marketing gimmick — cosmetics already use dozens of palm-derived ingredients. Making oil in the lab allows the creation of entirely new compounds that do things that ordinary palm derivatives cannot. And that can fetch higher prices.

“With precision fermentation, you can create novel profiles. So we create novel carotenoids that come from our yeast,” Ticku said. “They do great things for skin health, and that’s why a lot of the beauty brands want to use it. And they do pay much higher prices than they would pay for, say, just a functional palm thing.”

Has Palm Oil Cleaned Up Its Act?

For the champions of sustainable palm oil, lab-grown oil companies are “fighting the last war” of early aughts deforestation, rather than focusing on 2025 reality. They argue that the palm oil industry has made substantial progress since its time as one of the world’s chief environmental villains.

Consultant Judith Murdoch, who helps large palm oil producers through RSPO audits, said we should focus on fixing supply chains to be sustainable. Instead of boycotting or replacing palm oil, she argues that we should focus on preventing additional deforestation. It’s a “mend it, don’t end it” approach.

“No, there’s not going to be alternatives at scale,” Murdoch said. “Maybe in 50 years, there might be. But where’s the population at that point? Your only alternative now is to ensure that it is grown sustainably.”

Palm oil remains a major cash crop in Indonesia and other equatorial countries, including Malaysia, Thailand, Nigeria, and Colombia, with millions of low-income laborers and smallholders — not to mention wealthy landowners and corporate executives — depending on it for their livelihoods. If European or American environmentalists boycott the Indonesian product, for example, Murdoch believes the country will be happy to use it to create biofuel. Indonesia currently has a mandate to create biodiesel with 35% palm oil content, and may bump up the requirement as high as 50% next year. This has helped commodity prices double since 2019.

Felipe Guerrero, vice-president of a sustainable palm company based in Colombia called Daabon, said his company has been focused on reducing ecological and labor harms for the past three decades. Satellite imagery and remote sensors help the company watch existing rainforests, making sure that palm is grown only on existing pastureland and that no one among their suppliers destroys additional ecosystems. The company uses no-till farming, crop rotation, and cover crops to prevent soil depletion, and their farms became the first palm oil producers to be Regenerative Organic Certified in 2023. (They also received Rainforest Alliance Certification in 2012, and RSPO NXT certification in 2017.)

Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations, 2025

Daabon creates connecting sections of forests known as “biodiversity corridors” to allow wildlife to travel freely, and has restored sensitive turtle habitat near rivers as well as depleted mangroves. A family-owned business that produces more than 70,000 tons of sustainable palm oil annually, Daabon ships approximately 40% of its product to the U.S., where it has an office in Miami. As the umbrella term “sustainable” has expanded to encompass deforestation and labor standards, the company has been happy to adapt. In 1999, they launched an “Alianzas” program to purchase sustainable palm oil from small landholders — and they became the first palm oil producer to receive Fair Trade USA certification in 2016.

“It was thought that organic was ‘sustainable,’” Guerrero said. “But then having smallholders was sustainable. But then having ecosystem protection was being sustainable. And then human rights was being sustainable. So it has grown.”

With most palm oil grown on land that wasn’t deforested recently, even the biodiversity champions at the World Wildlife Fund argue against boycotting palm oil entirely — instead, they say we should focus on stopping additional deforestation and buying sustainable palm oil. And it’s not just to protect jobs in developing countries.

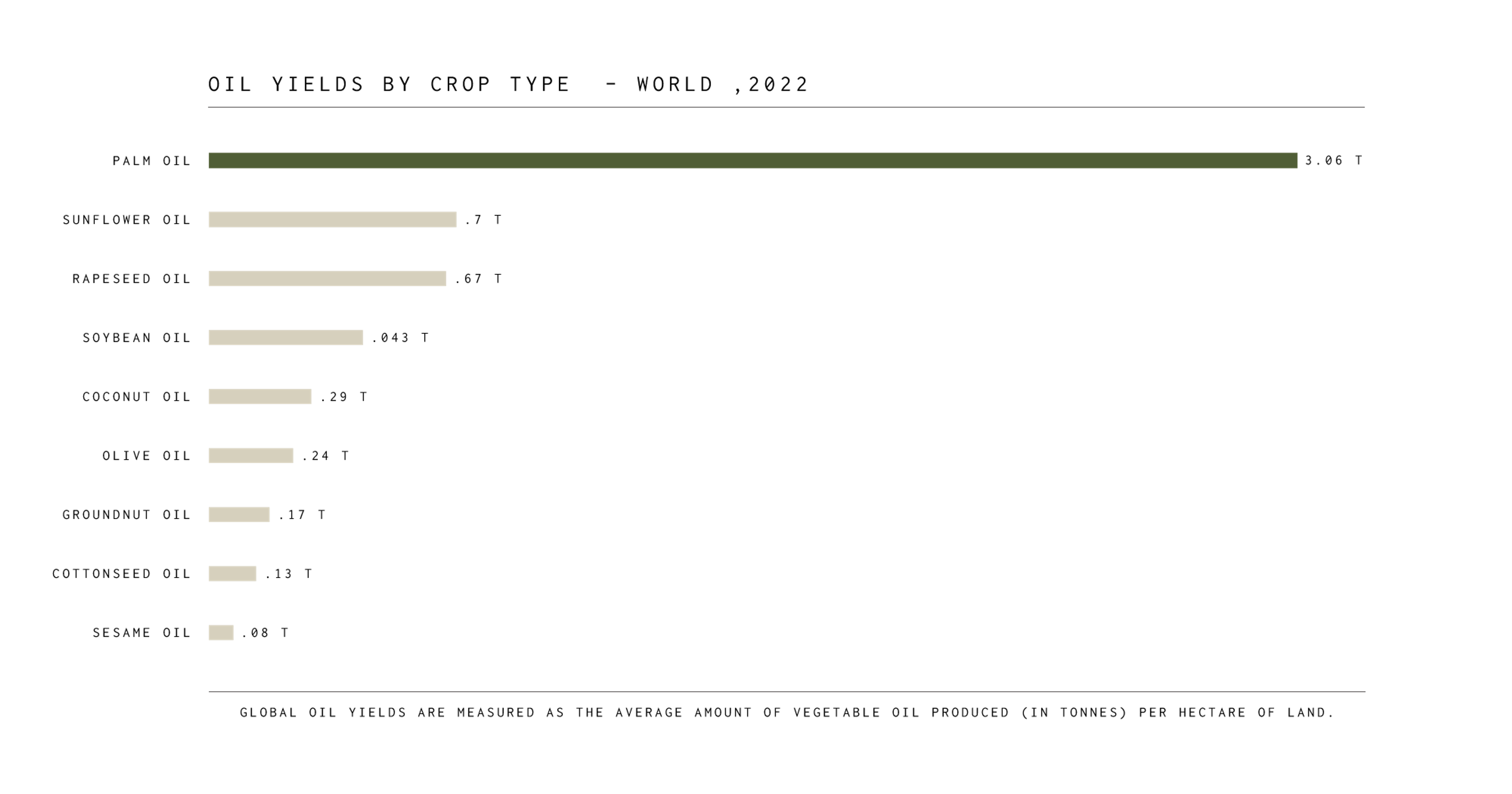

One of the reasons for the popularity of palm is that in these rare tropical ecosystems, the plant yields an extraordinary 3.06 tonnes of oil per hectare, making it more than four times as prolific as sunflower oil and more than seven times as prolific as soybean oil. And that’s before you get into its physical qualities that are so useful in food science and cosmetics, including spreadability, melting behavior, and texture.

With a boycott, you need to find an alternative. Switching to soybean from palm oil, for example, would require more than seven times as much land to yield the same amount of oil — which paradoxically could cause even more deforestation. (Even though soy grows in a much wider variety of climates.) And soy oil lacks some of palm oil’s desirable qualities for taste and texture: It is liquid at room temperature, is more likely to allow food to become rancid, and is not as stable at high temperatures.

Palm Oil Riches Are Hard to Resist

Not all producers are as conscientious as Daabon though. And high prices will always provide a strong incentive to cheat — there have been multiple recent cases of large palm oil producers using shell companies to circumvent deforestation or labor regulations. And besides, it’s not like the minority the palm oil crop marketed as “sustainable” is a magic bullet. One 2020 study found that 75% of Indonesian and Malaysian plantations certified as sustainable by the RSPO are located in places that were deforested in just the past 30 years — some would argue a “sustainability” label greenwashes that semi-recent deforestation.

There’s also what oil entrepreneur Lars Langhout calls “long-term supply” risk. Food scientist Le noted that global warming could lead to reduced palm oil yields in sensitive equatorial regions. “With increasing challenges from climate change, the palm tree will eventually suffer serious deficiencies in their ability to produce palm oil or even outright loss of their habitat. And of course, the demand for palm oil will only increase with more applications in the food industry, as the need for an oil that can solidify at room temperature is paramount to the mouthfeel and texture for many food products.”

Langhout said that No Palm Ingredients is indeed focusing on the market for specialty fats in both food and cosmetics because these are markets where texture and melting behavior are particularly important. But he doesn’t feel he can ask consumers to pay more for his product, just because it generates 90% less carbon dioxide and uses 99% less land than conventional palm oil.

Take it from the makers of plant-based meat, who have seen their product boom and then bust: Though a subsection of consumers are willing to pony up, most products struggle when they add on a “green premium.”

“With increasing challenges from climate change, the palm tree will eventually suffer serious deficiencies in their ability to produce palm oil.“

What makes No Palm Ingredients different from other lab-based oil makers is that it uses agricultural byproducts, rather than relatively expensive sugar, as the feedstock. In a facility under construction in the Dutch town of Ede, Langhout uses whey permeate, a sidestream from mozzarella production. Provided by Milcobel, the largest dairy co-op in Belgium, the whey permeate would otherwise be a low-value product sold as animal feed or for biogas production. Or Milcobel might have to pay to have it dumped in a landfill.

Though Langhout’s process could also work with potato peels or brewery waste, using a single uniform sidestream like whey permeate makes the biochemistry more reliable. It also saves money, because it costs about 50% less than the food-grade sugars used by many of his competitors. When completed next year, the factory will yield up to 1,200 tons annually of “no palm” oil.

But he’s not going to ask buyers to pay more for his product.

“They should choose it because it performs, is circular, and avoids the deforestation risk at price parity,” he said. “We don’t believe in a green premium.”