Carbon schemes offer farmers a way to both help the planet and grow their earnings. The reality is not so simple.

Along the banks of the Wabash River in southwestern Indiana, farmer Lance Unger and his family raise 8,000 acres of corn, soybeans, and wheat — staple row crops across the Midwest. But Unger, a third-generation farmer, has differentiated his farm from most by joining a relatively new trend: selling carbon credits.

Six years ago, Unger chose to “farm carbon” in a partnership with Indigo Ag, an enormous, well-funded agtech startup that pays farmers to implement practices purported to store carbon in the ground. This includes planting cover crops and reducing the amount of tillage on a parcel of land. By implementing these practices, farmers generate carbon credits (one credit per ton of CO₂ stored in the soil) that brokers like Indigo sell to other companies, which then offset their own carbon and market themselves as greener.

Joining the program made sense to Unger, since he was already planning on making his practices more sustainable — implementing no-till and cover crops — when Indigo approached his farm. “In our mind, it was money for stuff we were already doing,” he said. “The stars aligned.”

To fulfill his contract with Indigo, Unger keeps careful track of the practices on his farm: where and when crops are planted, how often they’re tilled, and when manure is spread or pesticides are sprayed. Then he turns that data over to Indigo, which verifies that his practices are leading to storage of carbon, then pays Unger for his work.

Most of Unger’s acreage is enrolled in Indigo’s program. Since partnering with the company, he’s added cover crops (plants meant to cover fields in-between growing seasons), and decreased the intensity of tillage on his corn and soybean fields. For his wheat crop, he doesn’t till at all. Unger said joining Indigo was a secondary benefit to his farming philosophy: Reducing tillage and growing cover crops is simply how he ensures high soil quality.

Indigo is one of many companies that offer so-called “carbon farming schemes,” acting as brokers between farmers who promise to sequester carbon in their soils and large corporations looking to offset carbon footprints. But while joining the carbon market made sense for Unger, complicated contracts, dense science, and a volatile market mean that such programs won’t work for everyone. Plus, scientists say the length and details of the contracts could limit the environmental impact such programs can have, especially while climate culprits like fossil fuel burning still exist. And any farmers involved in these schemes might have implemented sustainable practices anyway, meaning they’re being paid for carbon storage that would have happened regardless.

Still, practices supported by such schemes have few environmental downsides, and can offer farmers another stream of income so long as they’re willing to wade through the paperwork and understand what’s required to “farm carbon” effectively.

What, Exactly, Is Soil Carbon?

Agtech startups, farmers, and large companies are interested in soil carbon as a way to reduce carbon emissions from agriculture in an attempt to slow climate change — or at least make it seem like they’re trying.

According to Gregg Sanford, a scientist in the Department of Agronomy at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, soil carbon is one of the multiple “pools” of carbon that contribute to the global carbon cycle, by which carbon is continually exchanged between the atmosphere, living organisms, waste products, and fossil fuels. Other pools include carbon in the atmosphere, “biologic” carbon that exists in plants and animals, and carbon dissolved in the ocean. The amount of carbon in soil, globally, is more than the atmospheric and biological carbon combined, meaning that adjustments to soil carbon can have a big impact on the atmosphere and, therefore, the global climate, Sanford said.

Practices like no-till, low-till, and cover cropping have been promoted by both ambitious startups and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for helping sequester carbon. But Sanford cautions against the use of the word “sequester,” which he said could imply that carbon, once in the soil, stays there permanently. That’s not the case — rather, carbon is always being lost from soil as microbes break down organic matter. The goal, said Sanford, is to help carbon accrue in the soil faster than microbes are breaking it down and releasing it.

No-till and low-till practices are purported to keep carbon in the ground by slowing decomposition rates and reducing the frequency that soil is aerated. But, said Jennfer Pett-Ridge, soil scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, California, the science doesn’t fully support the claim that such practices increase soil carbon that wouldn’t naturally accrue. The practices simply “hold the carbon that’s there,” she said. That means carbon farming schemes could be paying farmers for helping solve a problem — carbon loss from soils — that might not exist had that land never been farmed in the first place.

“I think we’re at a state where we need to start with, ‘Let’s just not lose carbon.”’

Planting cover crops in between growing seasons increases the amount of time photosynthesis — the mechanism by which carbon accrues in soil — is happening on the field. As cover crops grow, they pull carbon dioxide from the air. When those plants eventually die, some of that carbon stays in the soil. Both reducing tillage and planting cover crops can also reduce erosion, improve soil quality, and lead to other environmental benefits like cleaner water, pollinator habitat, and biodiversity, said Sanford.

However, soil scientists say the depth of such changes is important to ensure any benefits to the climate. Most of the carbon lost from soils in the Midwest and Great Plains region, where much of American farming takes place, is lost from soils in the “deep horizon,” said Sanford — a layer of soil below that which commodity grain farmers usually manipulate.

Even though farmers can make improvements to the top layer of soil, said Sanford, loss from deep layers can offset any carbon gains. This means that even farms that are making carbon gains in the upper layers could still be losing carbon on the whole. Unless farmers or carbon programs are sampling the carbon levels in those deeper layers — not necessarily standard practice — it’s impossible to determine a farm’s net performance.

The recommendations for carbon monitoring by the IPCC are based mostly on studies that only measured top 30 centimeters of soils; carbon farming schemes rarely measure carbon in the deeper layers. “This is kind of baked into the way that we evaluate soils and soil carbon,” said Sanford.

Pett-Ridge urges caution as well. “There’s a lot of folks that are really bullish on the soil carbon increases,” she said. “I think we’re at a state where we need to start with, ‘Let’s just not lose carbon.”’

“There will always be snake oil salesmen.”

While cover crops and reducing tillage could prevent carbon loss from upper layers of soil, there are other targeted practices that could be considered in future carbon schemes. For instance, planting perennial crops with more extensive root systems could help hold carbon in the deeper layers of soil. Perennials stay green longer than annual plants, too, which means their potential to capture carbon through photosynthesis is greater.

There’s emerging scientific evidence to support other carbon sequestration methods as well, like the addition of biochar (charred organic material meant to trap carbon in soil long-term) or mycorrhizal additives (fungal amendments that increase the surface area of root systems). Pett-Ridge said she’d like to see more evidence that such strategies are effective at increasing soil carbon.

As with any emerging market, said Sanford, buyers should be cautious: “There will always be snake oil salesmen.”

However, said Pett-Ridge, carbon farming of any kind, no matter how effective, is usually a movement in the right direction. “I personally see more upside than disincentive,” she said. In the case of cover crops, especially, she said there are no downsides in terms of soil health.

Pay to Play

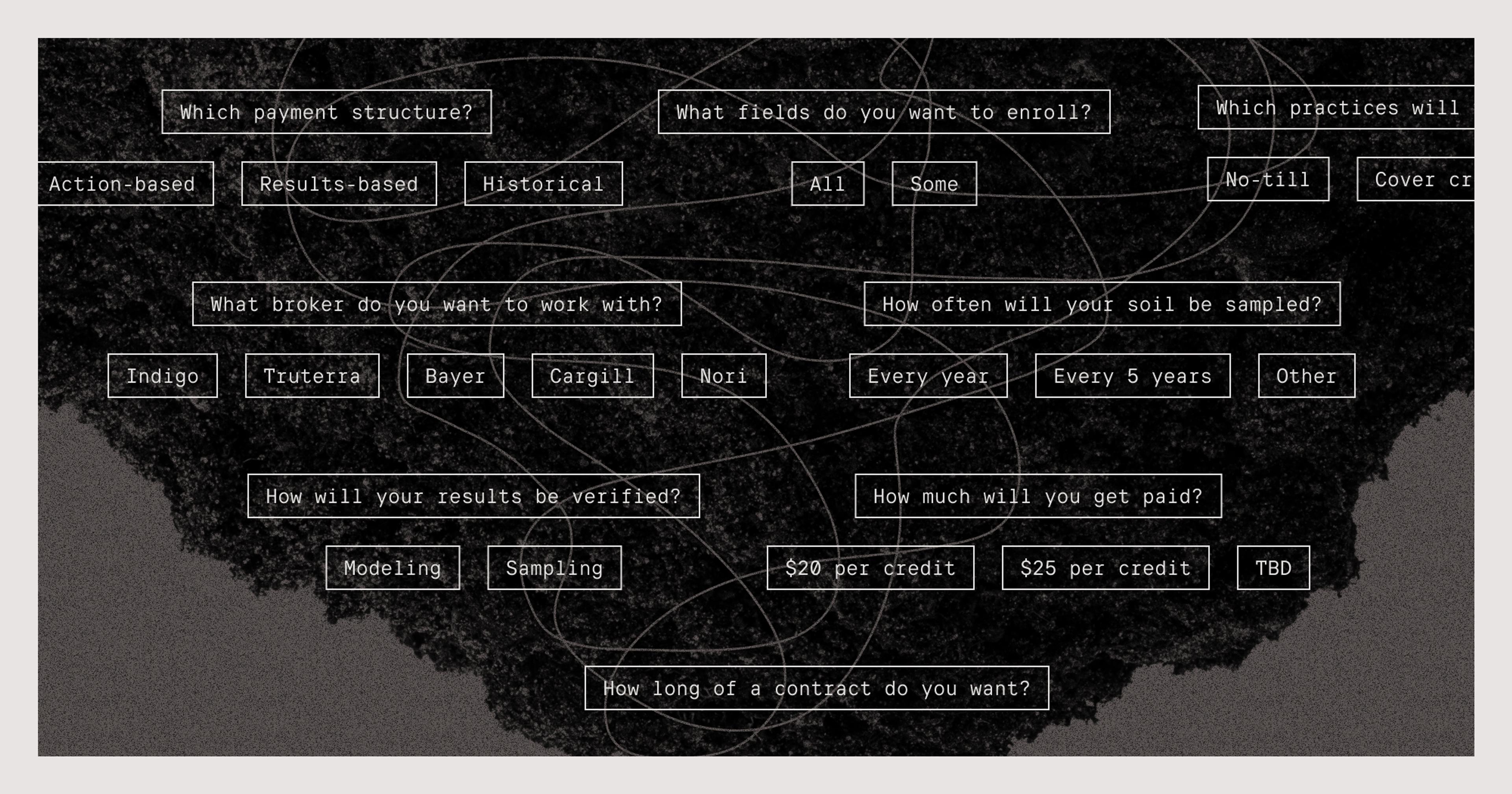

Multiple brokers currently offer farmers payments for generating carbon credits. In the U.S., some of the bigger players include Indigo (which is partnered with Corteva AgriScience), a program run by Land O’ Lakes called Truterra, Bayer’s Carbon Farming Program, and Cargill’s RegenConnect program. The bread-and-butter of these schemes is that certain changes in practices are verified by a third party and placed in a registry. Brokers work with the registry, the verifier, and the farmer, selling companies carbon credits generated by the changes in practices. The buyers are usually big brands like Walmart, Target, and others looking to offset their carbon footprint and make themselves more attractive to eco-conscious consumers.

The payments these programs offer farmers can take two forms, the first — and most common — being action-based payments, which reward the farmer for implementing a certain practice on a set number of acres. Then, based on approximations of the amount of carbon already in the soil in that region, and the amount of carbon the chosen practice can sequester, credits are generated.

The alternative payment structure is results-based, whereby brokers reward the farmer for measured changes in soil carbon. Results-based payments are typically higher, since action-based payment programs must reserve funds in case a farmer falls short of their carbon storage goal. Bayer, Indigo, Truterra, Nori, and Cargill all run action-based programs, though Cargill also offers results-based payments.

In 2022, Truterra paid farmers up to $25 per carbon credit, the same payment that Cargill is offering for 2022-2023 enrollment. Nori and Indigo pay $20 per credit. Companies that buy these credits then pay a slightly inflated price; for example, Nori sells credits at a 15% upcharge.

Jerome Dumortier, an agricultural economist at Indiana University, said action-based payments may be more prevalent since results-based payments require measurement of soil carbon before and after the change of practices, which can be “very difficult” to achieve since carbon storage varies from acre to acre. Measurement strategies also vary in accuracy; while some brokers verify results with actual soil sampling (the “gold standard,” said Sanford), others use modeling techniques based on soil type, climate, and other data. Soil sampling is expensive and can be logistically challenging, but Sanford said they are an absolute necessity for accurate verification.

Action-based payments can also offer reassurance to farmers, said Alyssa Cho, a member of Bayer’s agronomy team. “There’s a guaranteed payment for the grower. They don’t have to worry about how much carbon they’re actually going to sequester year over year.” Viewed differently, this means they are also less accountable for achieving results.

Paying farmers for practices they’ve already implemented is not “the purpose of a carbon payment.”

However, said Sanford, in order for action-based payments to stand up to scrutiny, they must be verified by soil sampling from time to time and must be compared against a baseline measurement. Bayer, for example, takes soil samples in year one and year five of a farmer’s contract.

For a farmer, the choice between an action-based or results-based payment program depends on the farm, the location, the soil type, and the amount of risk a farmer is willing to take on. If the farmer is in an area with high potential for carbon sequestration, said Cho, it might make more sense to go with a results-based program, but an action-based program can insulate a farmer in case the farm can’t sequester as much carbon as expected. “Some growers want that certainty and predictability,” she said.

Some companies, like action-based brokers Nori, Truterra, and Indigo, pay farmers for practices that have already happened, called “historical” or “vintage” credits. Nori rewards farmers for up to four years of changes in practices that have been made since 2012, while Truterra offers a lower payment for practice changes made since 2019. Nori also plans to offer farmers payments in the form of a blockchain-backed token.

Some experts say paying for historical changes in practices defeats the point, since no additional new carbon is being sequestered in the soil. Dumortier, for example, said paying farmers for practices they’ve already implemented is not “the purpose of a carbon payment.” Still, these programs surely hold some allure to farmers, in that they might not require drastically changing their practices in the future.

Considering a Contract

Lawyers, agricultural economists, and other farmers caution that joining carbon schemes might not make sense for every farm. Alexis Stevens, a fifth-generation Iowa farmer who grows 600 acres of corn and soybeans, has chosen not to enroll any of her acreage in carbon farming programs.

Stevens said the reason is simple: The numbers just don’t work. She believes that the cost of putting in cover crops, as well as the yield she expects she’d lose from no-till or low-till practices, means there’s little financial incentive for her to participate in the carbon market. With already tight margins, she’s hesitant to take the risk.

Reducing tillage can save farmers money on fuel, labor, and machinery costs, and cover crops can provide long-term economic benefits associated with improved soil quality. However, some research does suggest that no-till and low-till practices may decrease yield, and cover crops are an added up-front expense. That’s why, said Unger, the farmers choosing to sell carbon credits are generally those who are already implementing sustainable practices, or farmers for whom changing practices already makes financial sense, regardless of the carbon market. That means that brokers could be taking credit for storing carbon that might have been stored anyway.

That said, Indiana University’s Dumortier said there is huge potential for the voluntary carbon market to become the primary climate solution for farmers. He’s “optimistic” that they’ll be successful at a large scale since farmers are generally entrepreneurial and will jump at the chance to generate a new income stream. He also expects there to be a growing pool of money available for implementing climate-smart practices, whether it comes from the government or from corporations who want to market their products as climate-smart.

Corteva AgriScience projects that by 2030, farmers could make $60 per credit, while Bloomberg analysts recently wrote that they expect a $190 billion market by the same year. However, huge potential in early days means the market is crowded and unstable right now. There is currently no single carbon price offered by these different schemes, which Dumortier said leads to inefficiency in the market and uncertainty for farmers.

“Some years are good and others are a struggle. No need to think that this market will be any different.”

That volatility of the market, along with the number of different programs offered, could eventually be detrimental to the actual amount of carbon in the soil — if farmers have an incentive to break their contracts and switch between programs, once-sequestered carbon could be re-released, said Dumortier.

Additionally, said Dumortier, soil gets saturated with carbon at a certain point, meaning that payments would stagnate eventually for some farmers in results-based schemes. Depending on how the carbon farming scheme is structured, farmers could have an incentive to till up all their soil carbon and start anew, too. Some schemes have penalties for this, but Dumortier said “there would be no farmer” who wants to enroll in a program where payments would stop if soil became saturated.

Many components of the contracts required to join carbon farming schemes can scare off farmers, as well. Contracts with carbon farming programs range from one year (Cargill) to a minimum of 10 years (Bayer). Farmers may not want to commit to longer contracts since the market is so new and volatile; a contract a farmer signs now might prevent them from signing a new contract if the price of carbon rises rapidly in the next decade.

Additionally, commodity prices for crops change quickly, meaning that while one year it might make sense to take land out of production or change practices for carbon credit payments, the next year a hike in corn prices could make conventional farming more profitable. “It’s still the wild, wild West,” said Stevens.

“There’s a lot of rapid changes, and new faces coming to the table every day with new offers,” said Cho. “It’s a very confusing time for growers.”

Unger, on the other hand, said a volatile market is something farmers are used to with the grain market. “Some years are good and others are a struggle,” he said in an email. “No need to think that this market will be any different.”

Some farmers have been frustrated that large corporations are getting the glory for sustainable practices done by farmers.

Lawyers urge farmers to negotiate their contracts to lessen the penalties they’d face for switching contracts and to shift the costs of transitioning their farm’s practices to the broker. “From a producer perspective, there are a lot of changes I would want to ask for in the majority of the contracts that I’ve seen,” said Tiffany Dowell Lashmet, an agricultural law expert at Texas A&M.

In a white paper offered as a decision-making guide to ranchers, Dowell Lashmet and other agricultural law experts advise farmers to evaluate their production risk and potential: Since all farms have different soil types and climates, some may have a higher potential to accrue carbon than others. It may be less risky to join carbon farming schemes for farms with higher capacity to accrue carbon, they write. “It’s really important to understand the potential for sequestration in your own fields,” said Dowell Lashmet, adding that farmers in the Texas panhandle, for example, have far less carbon-storing potential than elsewhere in the country.

They also advised farmers to consider if any penalties exist in the contract in the case that the farm doesn’t accrue as much carbon as expected. Such clauses are called “no-reversal” clauses, and penalties could include termination of the contract, fines, or even return of prior payments, depending on the contract. Dowell Lashmet also said farmers should make sure they are able to appeal any determinations made about how effective their practices are.

Most programs, said Dowell Lashmet, require extensive data collection, and some even require aerial photography of farms in order to measure soil carbon and verify practices. “Farmers really value their privacy,” she said, “You’re basically going to open up your farm records, your farm books, all that kind of information. That has to be something you’re willing to share.”

The authors write that farmers should compare and contrast carbon farming contracts with other opportunities, like government programs and private payment systems, as some contracts don’t allow for the same acres of land to be enrolled in multiple programs at once (though, notably, Cargill allows farmers to involve their acreage in public payment programs alongside its scheme).

Given the many unknowns currently facing the system, said Stevens, many farmers have chosen to wait and see how the market shakes out; if the system becomes more standardized, more farmers might be interested. Some farmers may be expecting more government programs to start offering carbon-based payments, contributing to the hesitancy, said Dowell Lashmet.

Stevens also said some farmers she works with have been frustrated with the idea that large corporations are getting the glory for sustainable practices done by farmers. “I think they want a little bit more recognition,” she said.

Unintended Consequences

Some agricultural experts worry that carbon farming schemes might be preventing the agricultural system from transitioning toward even more transformative change that could make a bigger difference for climate and biodiversity. For example, Silvia Secchi, an agricultural economist at the University of Iowa, worries that participating in the carbon market gives farms an excuse not to cut back on other pollution- and emissions-generating practices, like fertilizer application. Carbon farming schemes, she said, “prolong the life of unsustainable systems.”

Sanford agrees. “There are many agricultural systems in the U.S. that are fundamentally not working well,” he said. “One of the big issues I have with this is that it’s a political kind of easy road to take, because it doesn’t ask us to challenge the prevailing agricultural paradigm to think about how we could farm.” Carbon farming, he said, allows farmers to keep planting corn and soybeans instead of exploring other ways to increase biodiversity and pollinator habitat.

“We shouldn’t convince ourselves that it’s a permanent solution, or even the most essential solution. The gorilla in the room is the combustion of fossil fuels,” said Sanford.

Dumortier, on the other hand, said voluntary carbon markets are the most realistic next step for adapting farming in the U.S. to a new climate reality. “We are driven by incentives,” he said. “People are not going to change out of the goodness of their heart.”