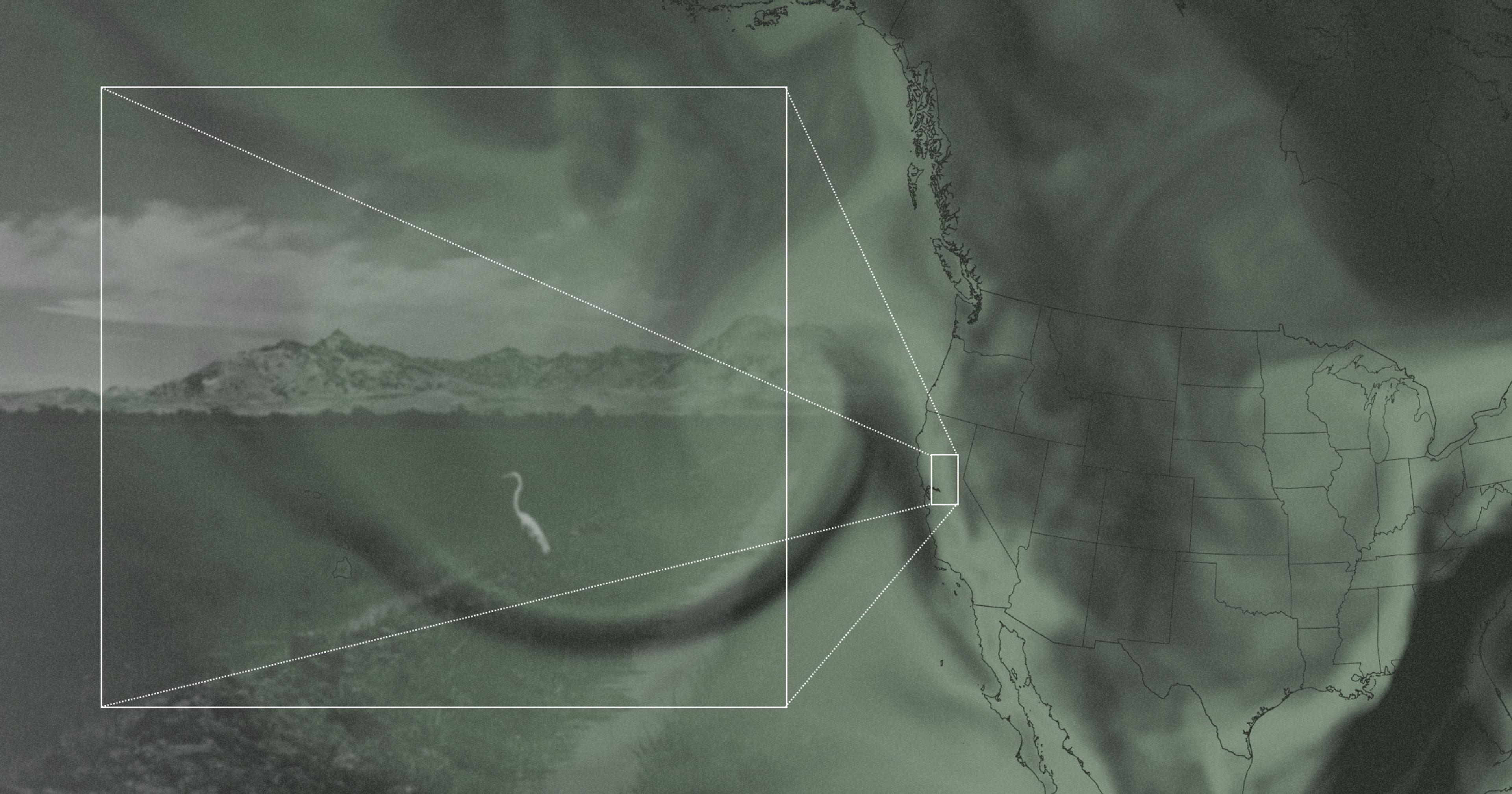

In the Pacific Northwest, a region of the country known for abundant rainfall, decades of droughts and resource battles are forcing farmers to learn about “dry farming.”

Born under cloudy skies in soggy northern Portland, my family moved to the tiny northern town of Page, Arizona — in a land where thirst is a constant companion. Surrounded by the Navajo Nation, I grew up with kids whose families have a long history of adapting to the climate of northern Arizona’s high desert.

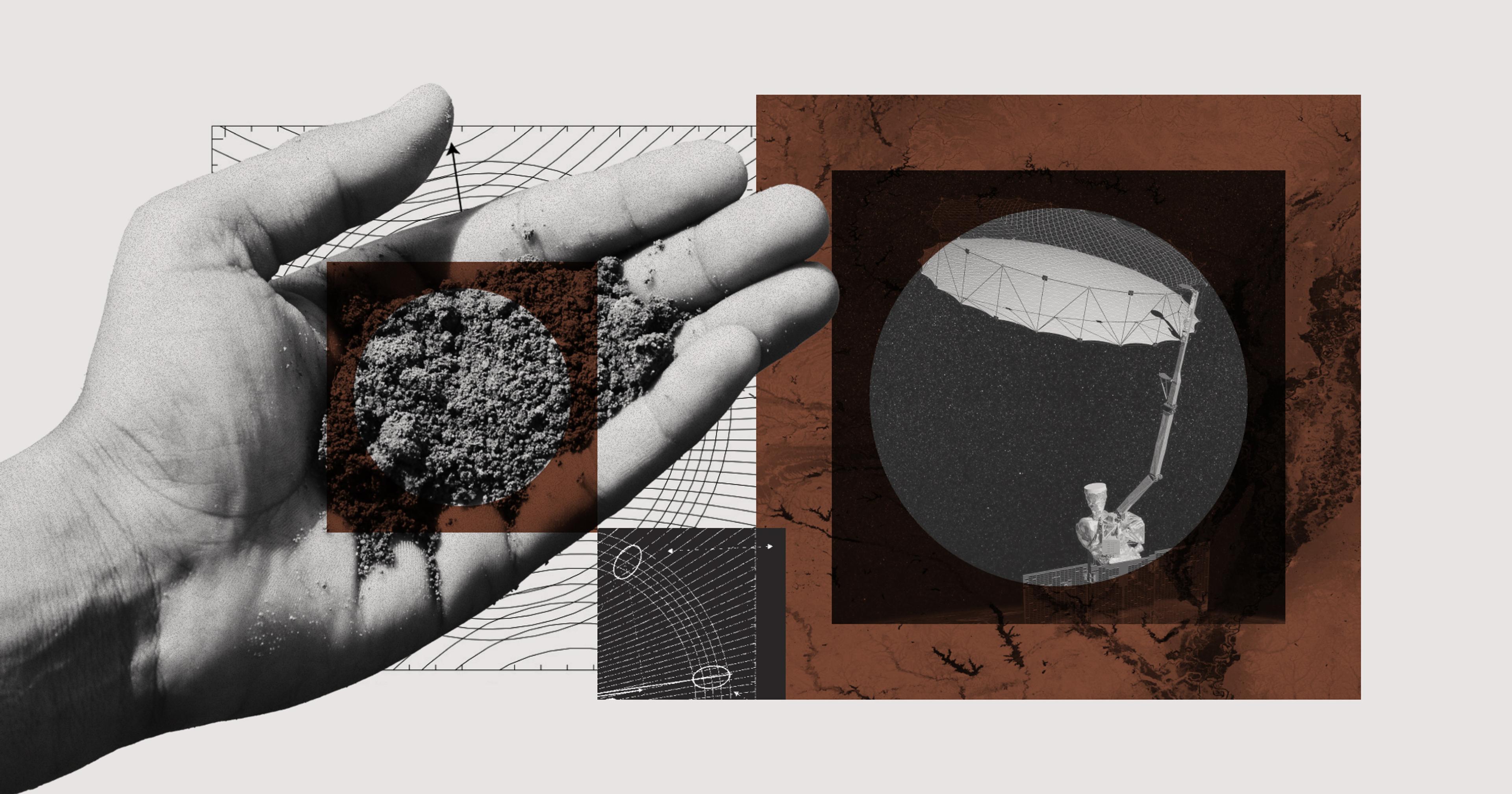

Best known for herding sheep, the Diné people mastered dry farming on the arid Colorado Plateau, drawing on generations of traditional ecological knowledge. They managed water with features like waffle gardens and berms, utilizing deep alluvial soils, and cultivated drought-tolerant crops, such as the “Three Sisters” — beans, corn, and squash. The sustainable system they developed relied on continuous seed saving and maintaining soil health with minimal disturbance.

It makes sense why their environment necessitated the Navajo’s year-round preparation for a brief planting season, adapting their food system to the arid climate of the Colorado Plateau.

Five years ago, I returned to the Pacific Northwest, where I now live with my sister on her 20-acre property in Western Washington. I was surprised to discover that growers in the Willamette Valley in Western Oregon, an area that receives around 35 to 60 inches of rain annually, were now on the lookout for more innovative ways to grow plants with less water. I couldn’t understand why farmers receiving that much annual rainfall needed to worry about water.

Wanting to understand why, and looking for resources that might help my sister and me conserve water ourselves, I reached out to Amy Garrett, director of operations at the Dry Farming Institute.

Amy’s involvement in dry farming began when she was working for the Small Farms Program at Oregon State University in 2011. She kept getting questions from new and beginning farmers facing unexpected water rights limitations and restricted access to irrigation. Traditional extension resources and conversations primarily focused on irrigated agriculture, which left water-poor growers somewhat up a creek without a paddle.

There is more to dry farming than simply turning off irrigation.

“I was having conversations with growers who had signed leases or were bequeathed land and were really just trying to figure out what they could grow after discovering they didn’t have water rights to the land, or it was a lot more expensive than they’d planned for,” Amy recalls. “It became clear after discussing soil type and drought-hardy crops that there was a significant knowledge gap regarding dry farming practices.”

For new farmers in Oregon, securing water rights presents significant challenges due to the state’s “first in time, first in right” water doctrine. This system prioritizes older water rights, meaning newer farms often face shortages, and water rights are not automatically transferred with land ownership. Many basins are already fully claimed or “over-appropriated,” making it difficult or impossible to obtain new permits, particularly in eastern and southern Oregon. This already complex situation is further exacerbated by the past two decades of persistent drought, which has strained water supplies and made existing rights even more precarious.

What Is Dry Farming, Actually?

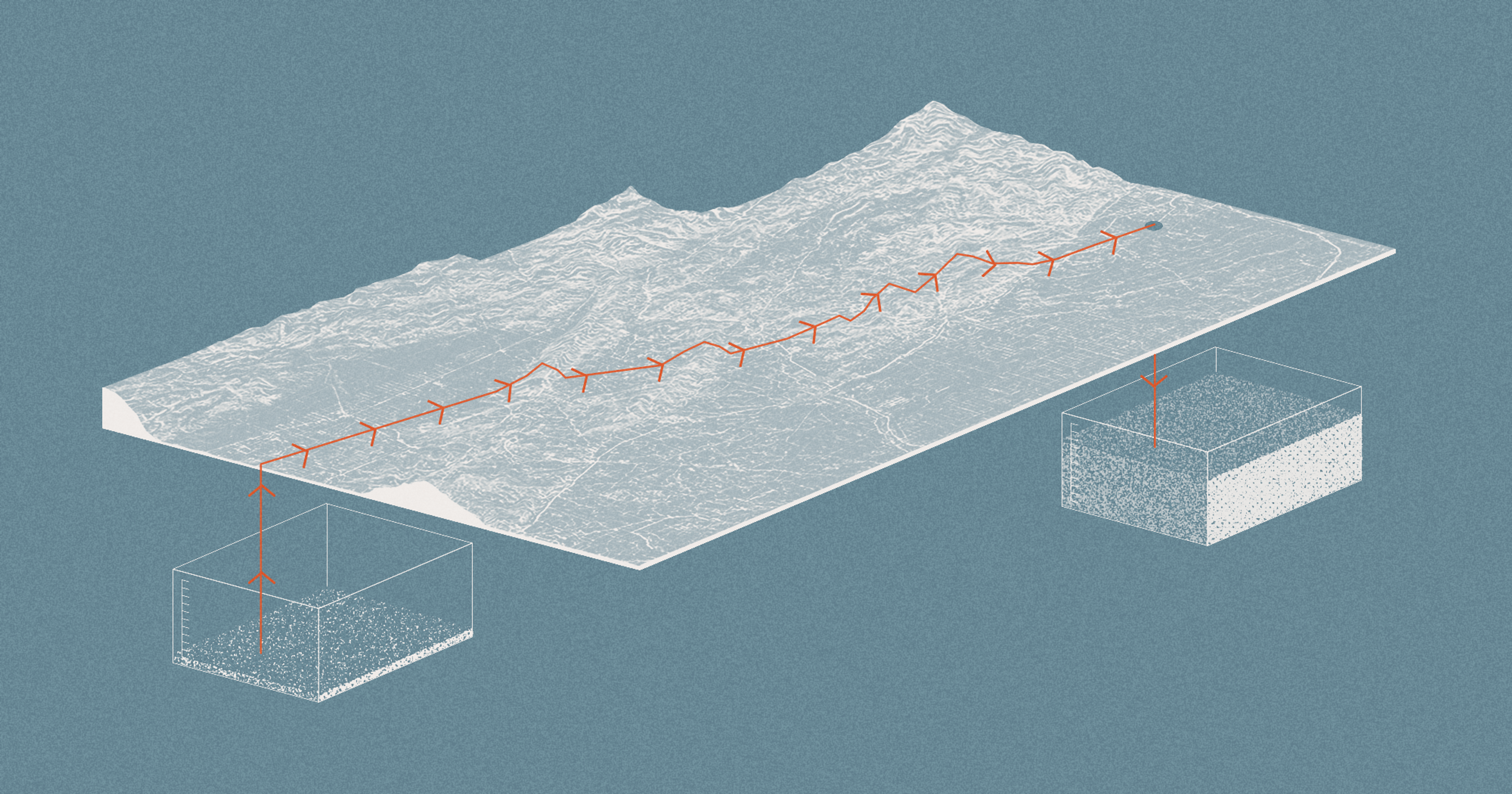

There is more to dry farming than simply turning off irrigation. The methods shared by the Dry Farming Institute rely on carefully selecting sites with deep, water-retentive soil and enhancing these conditions through practices like adding organic matter and precise soil preparation. Key to its success is planting at optimal times when soil moisture is present, often with lower plant density to reduce competition for water. Farmers employ moisture conservation techniques such as dust mulching throughout the growing season, alongside selecting drought-tolerant crop varieties, to grow crops with minimal to no irrigation. This encourages plants to access and utilize deep soil moisture more effectively.

The general definition of “dry farming” from their downloadable Dry Farming Zine toggles between terminology, but ultimately, “Dry Farming is rainfed [read: not irrigated] crop production during a dry season in a region that experiences 20 inches or more of annual rainfall.” In the maritime Pacific Northwest, winter rains replenish soil moisture yearly, giving growers sufficient water to grow crops without traditional irrigation.

But even in a region with over 20 inches of annual rainfall, Oregon’s food systems still have a water problem. In 2015, a severe drought in the Pacific Northwest led to early water restrictions, forcing many farmers to reduce or halt irrigation, which resulted in crop failures. The crisis highlighted the region’s fragile water supply and the challenges faced by those with junior water rights.

“It became clear after discussing soil type and drought-hardy crops that there was a significant knowledge gap regarding dry farming practices.”

A chance encounter with an experienced dry farmer applying the practices he’d learned from Italian immigrants inspired Amy to bridge the knowledge gap between farmers with practical experiences and growers needing dry farming insight. In the midst of that severe drought, she staged a pivotal demonstration to showcase the potential of dry farming in the Willamette Valley. Despite challenging conditions, dry-farmed crops thrived without irrigation, leading to a paradigm shift among attendees.

Today, the core purpose of the Dry Farming Institute is outreach and education, aiming to empower growers to thrive with less water through various initiatives. They develop impact case studies, sharing innovative approaches from active practitioners, and host virtual water resilience workshops, which are great for getting ag professionals and farmers together to network and trade insights.

This year, the Institute is also developing a water resilience toolkit — a practical guide based on extensive research, offering actionable steps and resources for increased water resiliency. All these efforts aim to build capacity, confidence, and community within the farming sector in Oregon and Washington.

Should You Dry Farm?

If dry farming practices work so well in the Pacific Northwest, why wouldn’t farmers adopt them everywhere? While the strategies developed in Oregon can help reduce water use in other regions, their suitability depends on climate, soil, and local conditions. Plants don’t need to develop deep roots in areas with steady summer rainfall (say, a Midwestern state like Indiana). In contrast, in Oregon’s dry summers, crops must reach deeper for moisture, training them to be perfect candidates for dry farming.

Amy suggests that dry farming is particularly beneficial for farmers in drought-prone regions or those facing specific water restrictions; growers looking to improve resilience to extreme heat; and regions with seasonal or intermittent rainfall, where farmers can use soil assessment, variety trials, and soil moisture sensors to reduce irrigation reliance.

But before you reach out directly to DFI, consider that their overall process of knowledge-sharing and experimentation can be replicated anywhere. I asked Amy whether dry farming is viable for large-scale corporate farms or if it’s primarily suited for smaller operations.

“I would have to say that depends on how a farmer defines success,” Amy suggested. “Corporate farms prioritizing maximizing yield and profit often rely on and have more access to traditional irrigation, making it less appealing.” Small-scale farmers often turn to dry farming out of necessity, due to water shortages, high irrigation costs, or a lack of infrastructure.

“A major advantage of dry-farmed produce, we’re discovering, is extended shelf life.”

“It’s just not a yield-maximization strategy,” she continued, “but a major advantage of dry-farmed produce, we’re discovering, is extended shelf life.” Despite yielding smaller sizes and quantities than irrigated crops, she said dry-farmed produce tends to store much longer, reducing waste. This is particularly beneficial for farmers marketing their produce over extended periods, as irrigated produce can rot in storage, negating its initial higher yield.

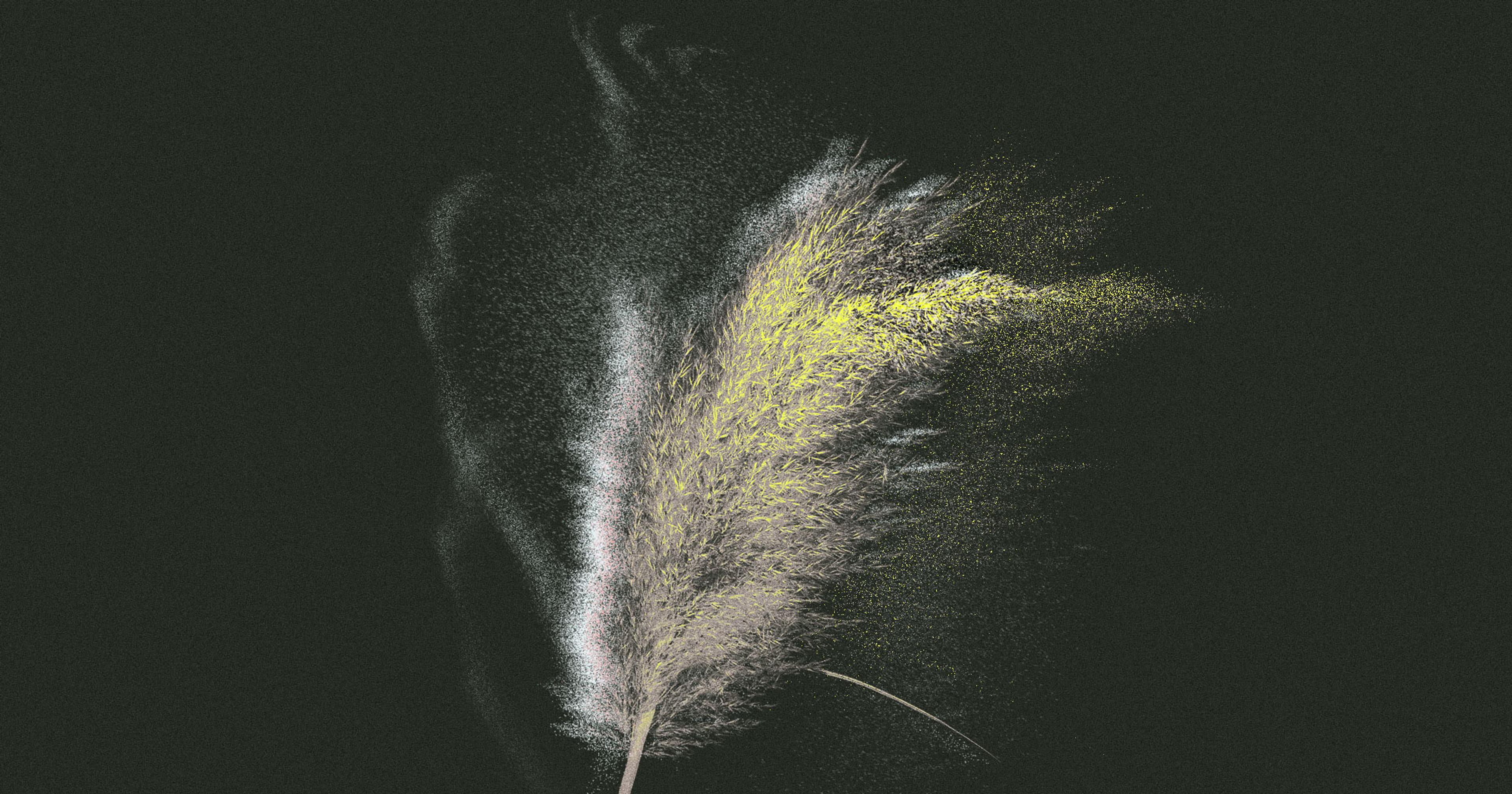

Longer shelf life and exceptional flavor turned Mary Colombo of Wild Roots Farm onto dry farming. Located near the confluence of the Sandy and Columbia rivers, the farm supplies a CSA and local restaurants in the metro Portland area with dry-farmed produce such as potatoes, tomatoes, winter squash, corn, and tepary beans, a legume grown by Native people since pre-Columbian times.

“I became interested in dry farming because it seemed so counterintuitive to grow crops without irrigation, but the results we’ve had are impressive,” admits Mary, who took her passion for food, gardening, and a desire for more meaningful work to a deeper level through the help of a farming incubator program, which eventually led her to the Dry Farming Institute.

Her biggest takeaways of dry farming? “I’m amazed by the wide variety of crops that can be dry-farmed,” she said. “The Dry Farming Institute is continually expanding and exploring new crops that can thrive in our region without irrigation.”

“Corporate farms prioritizing maximizing yield and profit often rely on and have more access to traditional irrigation, making [dry farming] less appealing.”

Growers who may not have initially had to worry about water restrictions may need to reconsider water conservation in the near future. With funding from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act helping farmers conserve Colorado River water, many are reconsidering their irrigation practices. If these financial incentives disappear, growers may face economic losses from reduced crop production, making alternative water-saving techniques like dry farming more appealing.

When I interviewed Amy in mid-February, she had just returned from a brief vacation to learn that a major grant, representing half of the Dry Farming Institute’s 2025 funding, had been frozen. This was likely due to its focus on “underserved producers” and “climate change” — phrases that are perceived as problematic by the current administration. On May 6, that funding was officially terminated. This cut creates substantial uncertainty for ongoing projects and additional hiring in 2025. It also makes relying on federal grants, the primary funding source for the past decade, unreliable.

While this is challenging, Amy acknowledges the opportunity to re-evaluate the organization’s priorities and potentially transform their approach to funding and programming. Like most people in the food and agricultural industries, they’re used to pivoting. Individual donors and the NoVo Foundation have already stepped in to help fill the gap.

“I’m trying to look at this setback as an opportunity to let go of some things that we don’t need to carry anymore,” said Amy. “A chance to transform the way we work as we continue to support growers in their efforts to produce food with less water.“