With water resources becoming ever scarcer, Golden State rice farmers look for ways to cut back on their usage.

The water allotments for California’s Sacramento Valley rice farms are in and things are looking up for 2023, with everyone (so far) on tap to receive full shares. For the region that produces most of the medium-grain sushi-style rice in the U.S. — over 500,000 acres of it in all — last year’s growing season was marked by extreme, unprecedented water cuts due to continuing drought conditions.

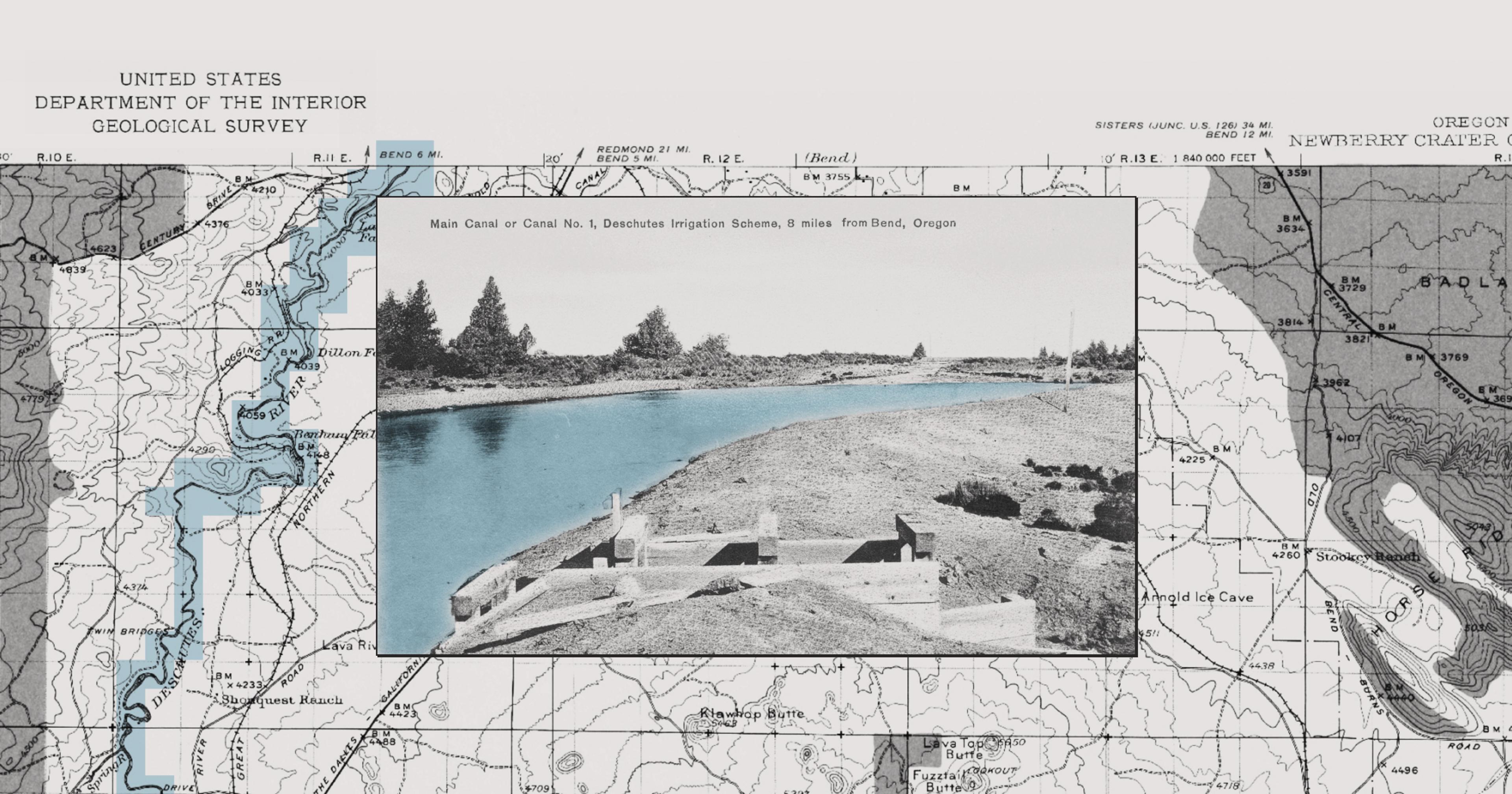

Rice farming is the fourth-largest user of water in the state after alfalfa, almonds and pistachios, and pasture. Growers in the Sacramento Valley are largely reliant on federal allotments of irrigation water from the Central Valley Project (CVP), a more than century-old system of water rights that are parceled out by the United States Bureau of Reclamation and delivered via a series of canals and aqueducts.

The water dearth is over (for now) thanks to 17 atmospheric rivers — storms dumping huge amounts of precipitation — that inundated the state between last December and this March, replenishing vital snowpack in the Sierra Nevada and boosting water levels in rivers and reservoirs. Rice farmers in the Glenn-Colusa Irrigation District, which gets CVP water from Lake Shasta, will receive 100 percent allocation; for comparison, these farmers received 0 to 18 percent of their usual water allotments last year.

Even producers with allotments on the higher side decided not to plant a crop in 2022 and in all, some 300,000 acres were left fallow. That resulted in an almost $1 billion loss. Steven Sutter, CEO of the rice company California Heritage Mills, told the Wall Street Journal, “In the rice industry in Northern California, no one has ever seen anything like this.” Rice farmer Jeff Sutton noted that 2022 was the first year his farm — which dates back to 1870 — had produced zero rice.

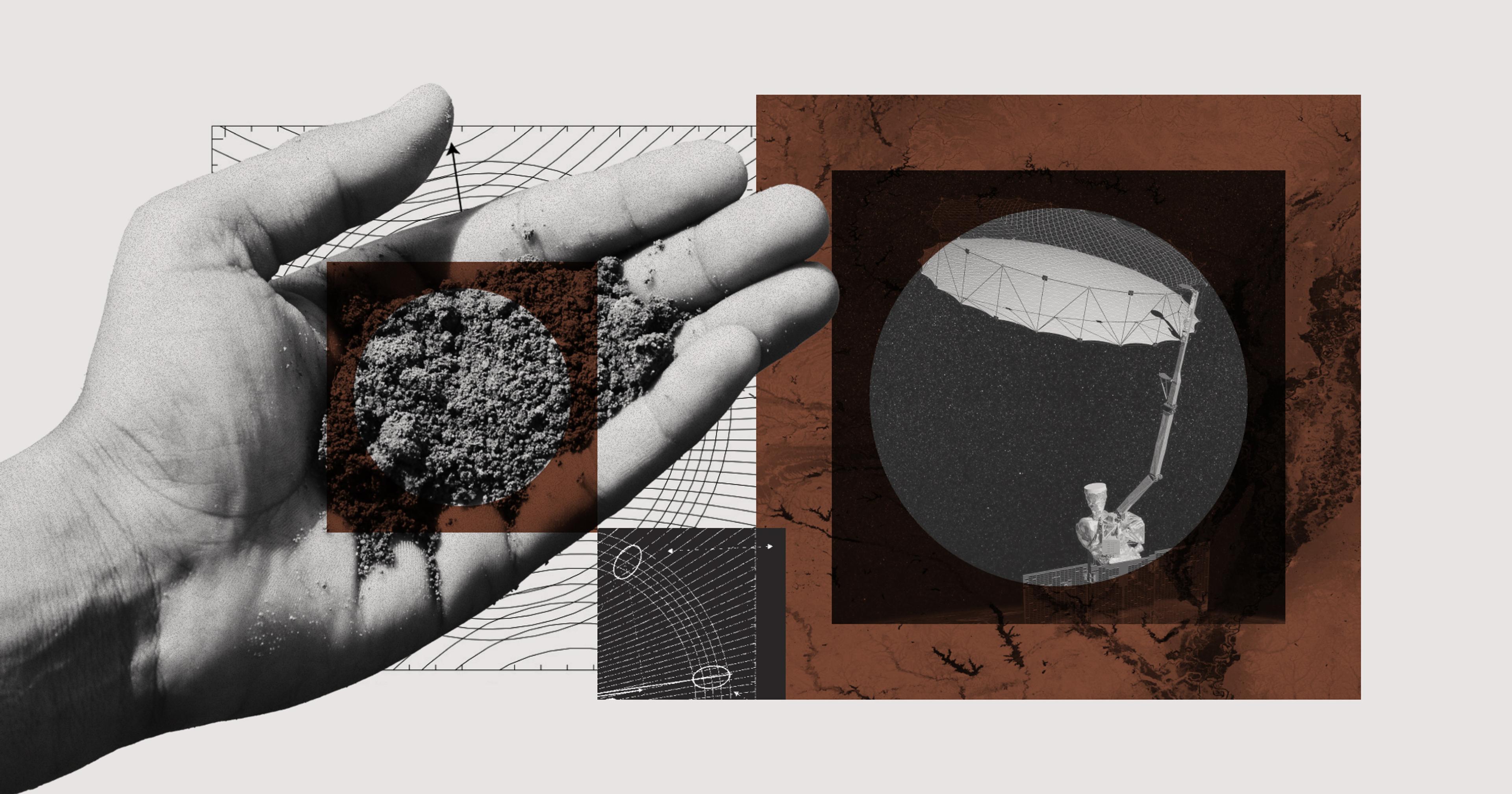

This year, “There’s a lot of optimism out there,” said Luis Espino, rice farming systems advisor for Butte and Glenn Counties at the University of California Cooperative Extension. But figuring out how to conserve water is, unsurprisingly, top-of-mind. To quote California rice farmer Matthew Garcia in an interview last year: “Without the water, we have dirt. It’s basically worthless. It’s very depressing.”

When there’s no water, there’s no rice, and no one is naive enough to believe that drought will never come again or that the state’s rice production is saved forever. “Growers have to think about this as the new normal, where some years we have water and some years we don’t,” Espino said. Which means strategies abound for ways to prepare for upcoming water shortages in order to become more resilient.

Rice fields are usually flooded in advance of planting — rice seed then gets dropped in by plane — and are replenished with a constant trickle of irrigation water throughout the growing season to keep weeds from taking over. This uses plenty of water in a state that typically gets little if any rain in spring and summer and is becoming more prone to water shortages; according to the University of California, a typical rice field requires 5 acre feet of water in a growing season. (An acre foot is about 326,000 gallons, which covers one acre of land to a depth of one foot.)

Still, there are some ways farmers can reduce their water usage. First, said Espino, they can use a rice varietal that doesn’t take as long to mature and harvest: “That way, instead of 150 days you’re in the field 140 days and that’s [10] days you don’t have to keep the field flooded.”

“Without the water, we have dirt. It’s basically worthless. It’s very depressing.”

Another option: Let the water subside from a field by a couple of inches before adding more water to it. This practice has its limitations, though; Espino pointed out that growers with high-salinity soils have to keep the in-and-out water flow constant, so that salts don’t accumulate and “hurt the rice.”

Number one (long-grain) rice producing state Arkansas saw record levels of drought in 2022, too. But there, rather than fields fed by surface waters and canal systems, farmers “have historically relied on pumping from underground aquifers,” said Anna McClung, research geneticist at USDA’s Dale Bumpers National Rice Research Center. Recent research shows that counties with high rice acreage are also the ones with critically low water levels.

Arkansas rice farmers have responded by laser leveling their fields, for a more uniform spread of water; and by spreading water via poly pipe to allow good control of where water flows in a field. This contrasts with “what’s called cascade irrigation [on sloped land], where you start to water at the top and it flows all the way down to the bottom,” which is inefficient, McClung said.

Farmers in California adopted precision leveling for their land some years ago, although, for reasons he’s not quite sure about, Espino said poly pipe systems never caught on in his state, possibly due to their steep cost. Although farmers in both states recognize the need to conserve water, they still have concerns about, “what’s going to be the consequences if you don’t have a flood,” said McClung. First concern: weed control, since keeping weeds in check is one of the main reasons farmers flood their rice fields in the first place. McClung said herbicide-resistant rice strains are making this less of an issue in Arkansas; according to Espino, a resistant strain will be on the market in California for the first time in 2024.

Second concern: loss of crop yields, although here again, McClung said, “We’ve found that if you do close management of your water, you do not lose yield.” That means making sure water remains at an even depth across a whole field, and that applies to farmers in California and Arkansas alike. In Texas, which grows about 225,000 acres of (mostly herbicide-resistant) long grain rice annually and whose farmers will likely not be allocated Colorado River water for the second year in a row because of continuing drought, these discussions are currently moot. Nevertheless, McClung said Texas farmers haven’t adopted many water-saving techniques, preferring to do things like reduce acreage instead.

“We found that if you do close management of your water, you do not lose yield.”

Back in California, Espino said that crop insurance — an increasingly divisive topic in conversations about the Farm Bill — has become of paramount importance in helping rice farmers weather drought. “That way you can at least survive [fallow] years,” he said. Last year, some rice farmers recouped some losses by selling their scant water to almond and other tree growers.

A novel way rice farmers can help survive drought years has the side advantage of helping native bird populations. Farmers can tap into conservation funds from sources like USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service and the California Winter Rice Habitat Incentive Program. In some cases, said Espino, farmers “might not be able to grow a crop, but they might have just enough water to flood a field to provide habitat.”

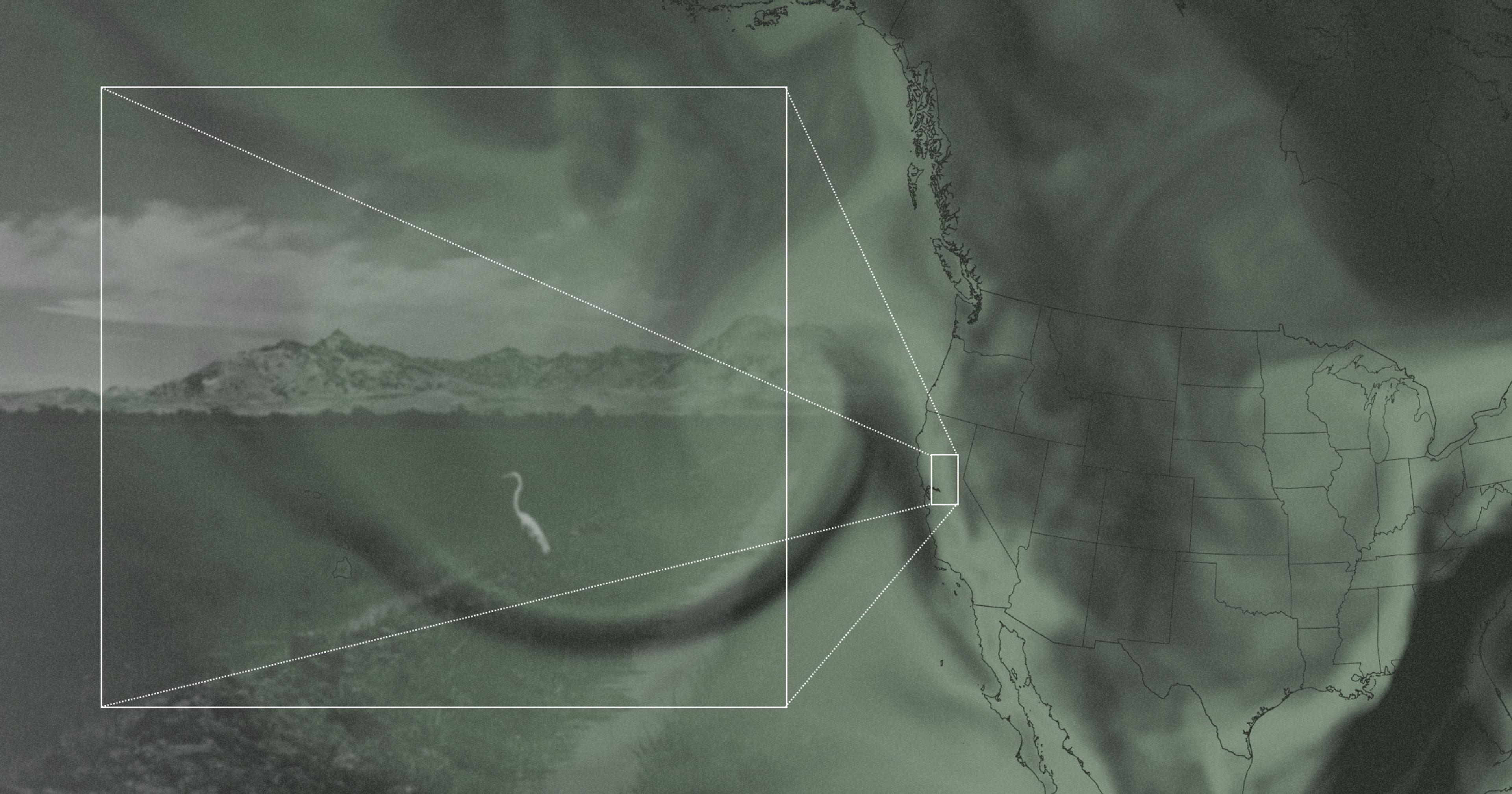

Central Valley is a critical nesting and foraging area for both endemic birds and those migrating along the Pacific Flyway. About 92 percent of the Valley’s historic wetlands have been lost to farms and other development, making rice fields extra important places for birds to land, to nest, and to eat waste rice that’s scattered after harvest. (Don’t believe the myths.)

The way it works, said biologist Kristin Sesser, the California Rice Commission’s wildlife programs manager, is that a program may pay a farmers anywhere from $15 to $80 an acre, depending on the practice and the time of the year, to put some water on their fields “to act as surrogate wetlands.” This practice has additional benefits for farmers, since water helps break down rice stalks, and the birds “mucking around” speeds that process along, Sesser said. Of course, if there’s zero water available — like last year on Sacramento Valley’s west side — rice farmers and birds all lose. “That isn’t something anybody wants to see again,” Sesser said.

Meanwhile, continuing spring showers in California have led to another problem: rice fields too soggy to plant. If seed’s not in by June 1, that means “lower yields and a very high risk of harvesting during fall rains that make harvest very difficult,” Espino said.