It’s all hands on deck in the West’s open rangelands to try to eliminate this wildfire kindling. But as it fuels more intense fires that kill off native grasses, that’s getting harder to do.

On July 5, 2018, sparks ignited just outside the rural town of Paradise Valley, Nevada. The small fire quickly exploded across the landscape with 40-foot flames and a smoke plume so huge, it was visible from space.

The Martin Fire ended up being the largest in Nevada history, consuming more than 431,000 acres. It blackened prime grazing land and critical sage-grouse habitat.

While the specific cause for the inferno is unknown (it was likely caused by fireworks or campers), experts are well aware of what helped launch it out of the canyon where it started to spread across 11,000 acres within an hour — a brittle ladder of cheatgrass growing up the sides of those canyon walls.

Cheatgrass, also known as downy brome, now covers well over 100 million acres of land in the United States. Over the past century, this non-native annual grass has sowed itself across the Great Basin and intermountain west, usurping rangelands that had been degraded from overgrazing and populating fields abandoned during the Great Depression.

It is one of the most problematic weeds in the West, depriving grazing animals of consistent, quality forage and killing off native bunch grasses and sagebrush that provide habitat for wildlife. As native flora struggles to survive in the face of increasingly frequent, hotter fires that are exacerbated by cheatgrass, the invasive weed gets even more space to spread out. The problem is so extensive that ranchers and governmental agencies have forged an unlikely wartime alliance to eradicate (or at least curb the spread of) cheatgrass.

The winds were fierce and temperatures were scorching when the Martin Fire erupted. It had been the second wet winter in a row, which led to a dry sea of grasses that had grown somewhere between 200 to 1,000 percent more than usual. The native perennial grasses were essentially waiting to explode, and the cheatgrass that had inserted itself into what would have been bare soil — that could’ve helped to slow the inferno — added flashy fuel to the fire.

“Historically rangeland would have gaps to slow down fires,” said Jacob Powell with Oregon State University’s agricultural extension faculty in Sherman and Wasco counties. “With cheatgrass filling in those gaps, there’s a continuous fuel bed once a fire gets started.”

Cheatgrass poses multiple issues for ranchers. Increased fire risk is the most obvious, but it also outcompetes native bunch grasses like wild rye and Indian ricegrass. These bushy stands grow in clumps with fibrous root systems that help to control soil erosion, sequester carbon, and retain moisture into the dry summer months. Native bunch grasses stay green well into the fire season, offering livestock a longer timeframe for grazing.

Cheatgrass can be grazed while it’s green; however, that window lasts a couple of months at most in the spring and should be done at specific intervals to help eliminate it and prevent it from spreading. Once it starts to turn purple, its barbed seeds can cause abscesses and wounds in animals’ mouths.

“There’s a heck of a lot higher chance fires will start from roads if there’s dense cheatgrass.”

After more than a century of unfettered spread, cheatgrass is now considered in all project planning efforts that involve public lands and has become a vital element within the National Environmental and Policy Act (NEPA) process. The first major environmental law in the United States, it requires federal agencies to assess the environmental effects of proposed actions in all decision-making processes. In the case of cheatgrass, if a project might spread the invasive plant via machinery or, say, a drilling company was applying for permits in an affected area, mitigation measures must be incorporated into the plan in order to gain approval.

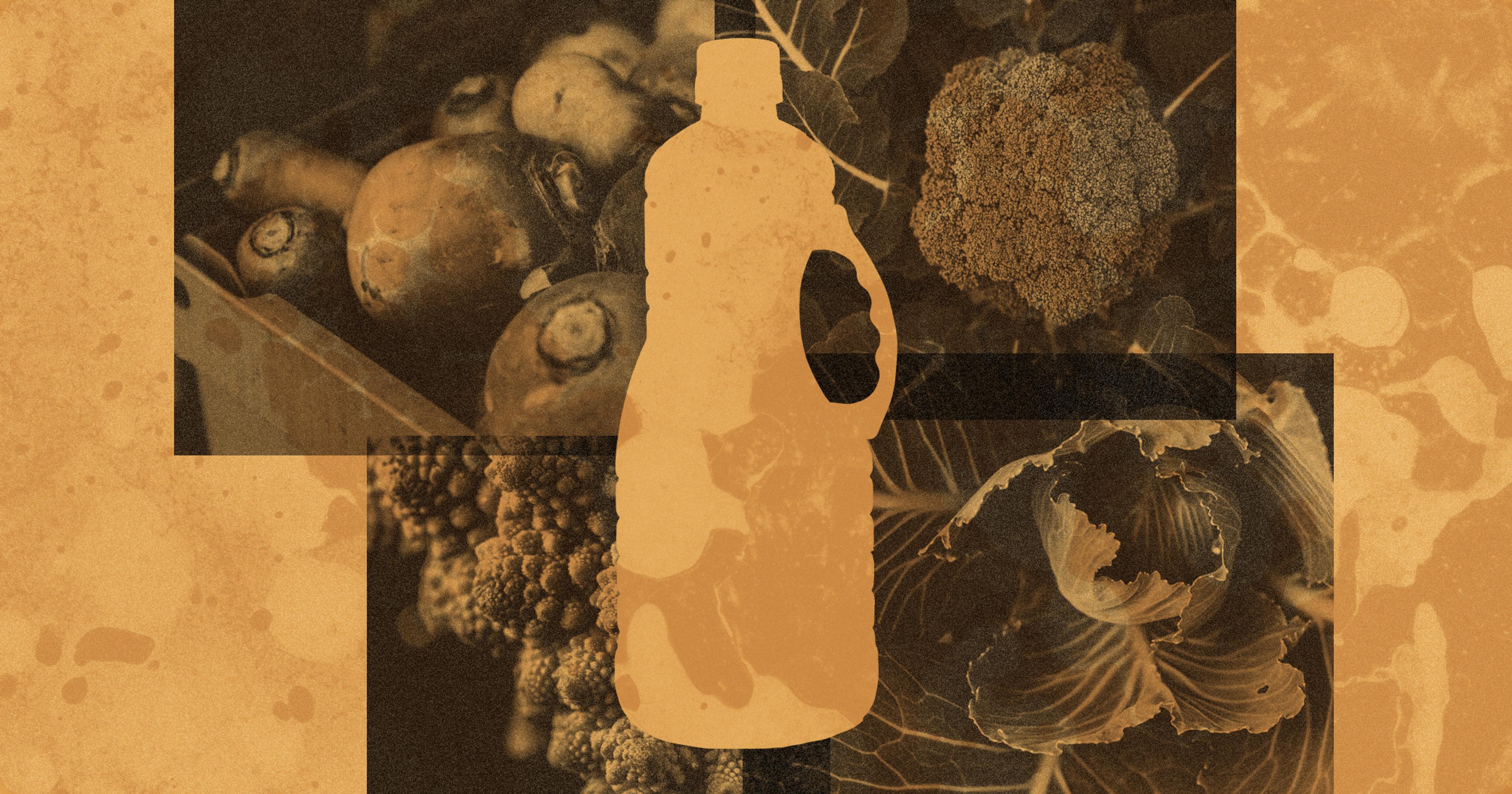

In particularly fire-prone regions, government agencies have been using aircraft to spray herbicides like Imazapic and Rejuvra on extensive areas. This includes 1,000 acres of BLM-managed land on the Yarmony Mountain area of northern Colorado and 9,200 acres that were burned by the 2020 Mullen wildfire in Wyoming.

Because the cheatgrass problem is so extensive, agencies have to carefully consider the most effective places and methods to attack it.

In southeastern Oregon, as part of a wildfire mitigation bill, 70,908 acres of private, tribal, state, and federal lands have been aerially sprayed with pre-emergent herbicide. Some of these applications have been directed toward protecting healthy bunch grass communities from encroaching cheatgrass. In other areas, the efforts have been aimed at eradicating swaths of invasive perennial grasses along roadsides. “There’s a heck of a lot higher chance fires will start from roads if there’s dense cheatgrass,” said Katie Wollstein, rangeland fire specialist with Oregon State University’s Forestry & Natural Resources Extension Fire Program. “It’s thinking about how invasive grass communities may function to spread fire across the landscape and taking a large-scale approach to managing fire risk.”

Though these aerial and on-the-ground sprays have become a popular and effective way to cull large spreads of cheatgrass and other similarly flammable invasives, the weeds are incredibly skilled at populating or repopulating bare ground. So, these sorts of chemical treatments are most effective when paired with reseeding native and immigrant bunch grasses.

Southeast Oregon’s fire resiliency plan also included seeding 300 acres with grass and shrub seeds including native plants that have been collected from Harney County and neighboring Malheur County. “Things like herbicide are a valuable tool, but unless you can get something desirable growing back in its place, you’re going to end up having to control the weed again,” said Dustin Johnson, extension rangeland scientist at Oregon State University.

“Things like herbicide are a valuable tool, but unless you can get something desirable growing back in its place, you’re going to end up having to control the weed again.”

These reseeding projects are one area where governmental agencies and ranchers have been working together across the West. Stakeholders in Oregon’s wildfire resiliency efforts are now planning to collaborate with landowners to grow those hand-collected seeds for ongoing restoration efforts. Similar reseeding projects using both native and non-native grasses have taken place in Utah after the Goose Creek Fire, following the The Pony and Elk complex fires in Idaho, and many other areas.

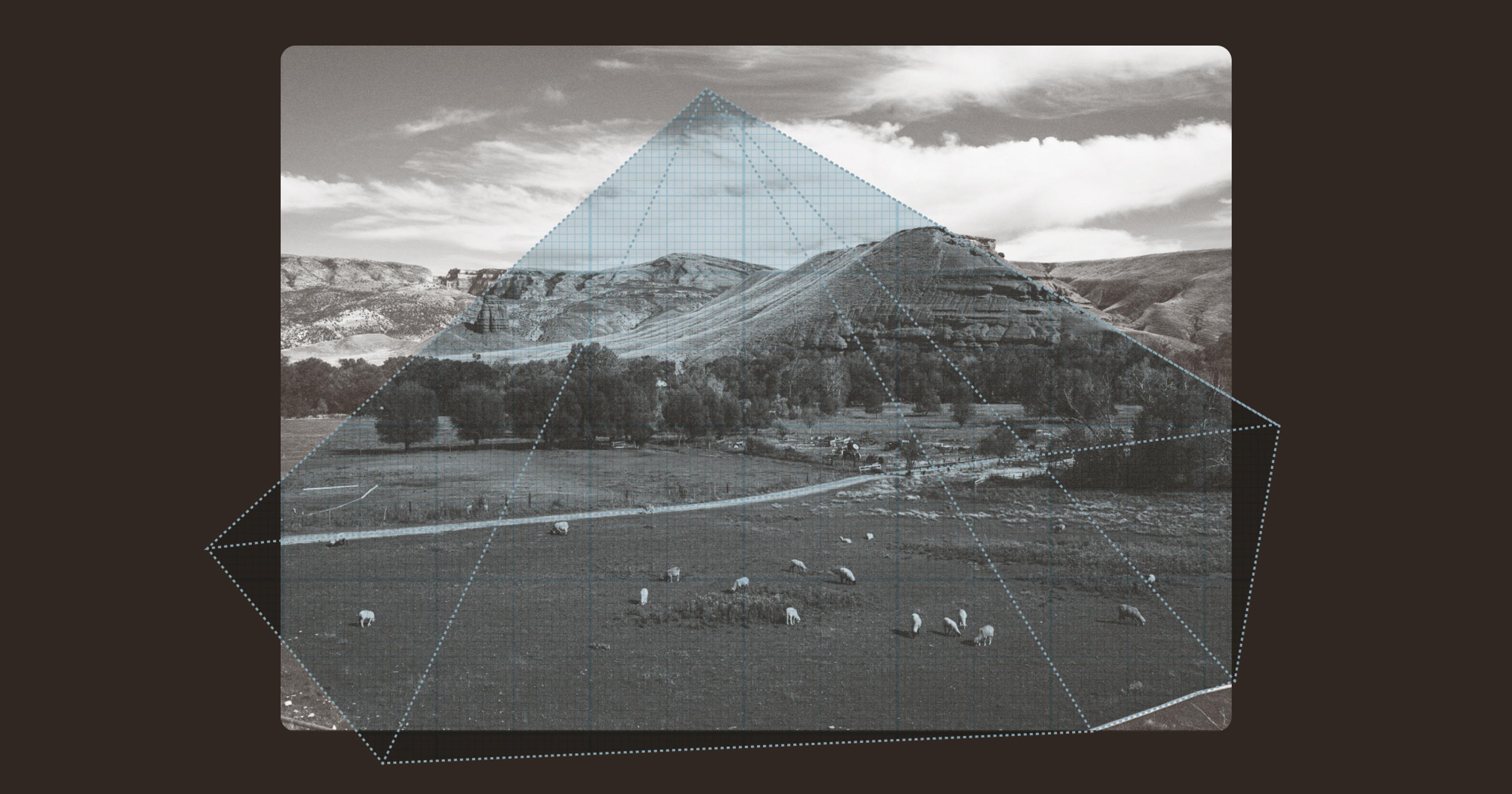

These projects have required a change in mindset regarding who is responsible for managing rangelands and how to do so in a way that best protects communities and the environment. “Lands in the American West have checkerboard ownership with private and public lands,” said Wollstein. “We need to work better across those ownership boundaries because invasive annual grass control is a collective action problem.”

Withers Ranch, a cattle ranch outside of Paisley, Oregon, has been hit with three different fires over the past five years, starting with the Watson Creek fire of 2018. It lies right on the edge of the Great Basin on the sagebrush steppe, bordered by conifer-heavy Fremont National Forest to the east. Though cheatgrass has not been the main driver for the fires that have swept through from different directions over recent years, owner Daniel Withers has been aggressively trying to contain it and similarly invasive medusahead from the bare ground where the fires burned. He has reseeded with a mix of crested wheat, wild rye, intermediate wheatgrass, and some forage kochia. “We’ve been pretty aggressive about seeding everywhere we could, both mechanically and aerially, to keep cheatgrass and medusahead out,” said Withers.

This reseeding is not only helping to make the land more fire-resistant but also is better at holding the soil together, which helps to support forage and water-holding capacity. Plus, it gives Withers a much longer window for grazing. He plans his grazing to take advantage of the cheatgrass while it’s still green and palatable to his cattle before it dries out. But he has to be fast. “The time with cattle is pretty short,” said Withers. “Maybe two weeks.”

Though BLM and other governmental agencies are now addressing cheatgrass from multiple angles including mechanical removal, herbicides, and prescribed burns, well-managed grazing is a critical piece of the problem that crisscrosses private property, grazing allotments, and other public lands. In some areas, virtual fencing has been used to contain cattle grazing cheatgrass along fire-prone roadsides. These sorts of efforts can play a huge role in preventing wildfire from spreading uncontrollably to neighboring properties. “Coordinating livestock grazing is an important treatment tool to address this really complex problem,” said Wollstein. “Ranchers are an important part of this.”