For 40 years, a group of wild cattle have grazed the Gila Wilderness in New Mexico. In efforts to remove them, the Forest Service is using lethal measures — leaving many in the ranching community upset.

Flash back to the 1950s, and New Mexico’s Gila National Forest, the sixth-largest national forest in the nation, set aside some of its land for domesticated cattle to graze. Two decades later, stray cattle, likely either lost or abandoned, began to wander the wilderness uncared for.

Ever since, the descendants of the abandoned herd have roamed the area and reproduced, leaving locals uncertain what to do with them.

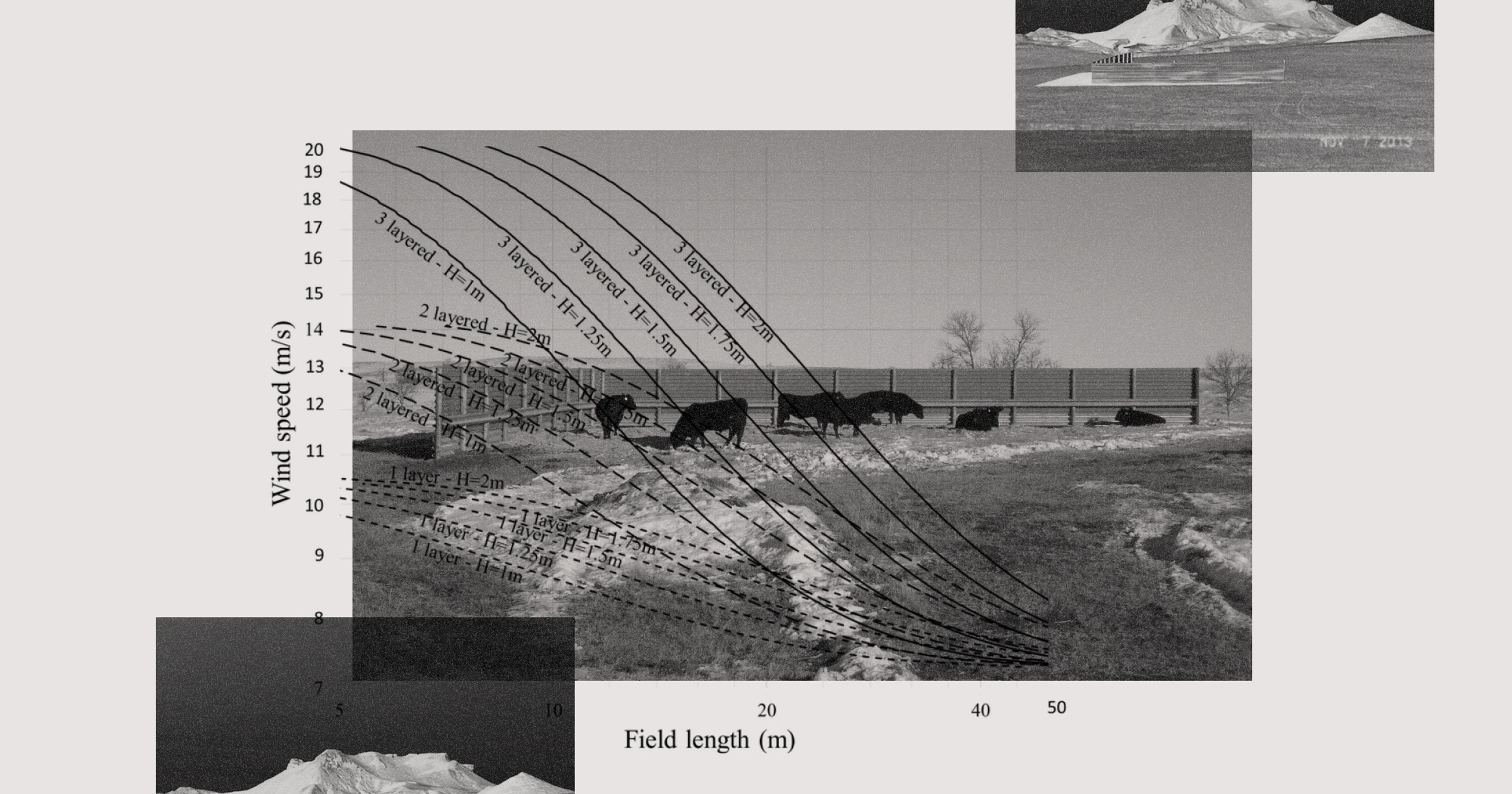

The U.S. Forest Service, along with the Center for Biodiversity, point to the cattle as a harm to the endangered species and environment within the wilderness. The groups said the cattle have a negative impact on the riparian forest surrounding the Gila River, as well as the water quality of the river itself. In the absence of cattle, environmentalists believe the health of the ecosystem would improve dramatically and quickly — leaving them eager to rid the area of bovines.

In the latest effort to remove the cattle that have openly wandered the Gila Wilderness for nearly four decades, the Forest Service made the decision to shoot the herd of “feral” cattle from helicopters flown above the forest, and leave the carcasses to rot. The action, which took place most recently in February, left at least 19 dead cows — and folks in the cattle industry up in arms.

Loren Patterson, president of the New Mexico Cattle Growers Association (NMCGA), is among the ranchers who have been working to stop the aerial shootings.

“We’ve been consistent in opposing it. And a reason why is some of those cattle could belong to a breeding allotment,” said Patterson. The wilderness, he said, is “not particularly far from working ranches.” Because the fences that keep ranchers’ cattle separate from the feral cows are often broken down — thanks to damage from recent forest fires and the area’s high population of elk — ranchers are concerned that some of these cattle are not, in fact, feral at all.

The February aerial action is not the Forest Service’s first attempt to rid the wilderness of the cattle. Ground-based and aerial removal efforts to reduce the cattle population — which has been hovering around an estimated 50-150 cattle, based on on-the-ground surveys — have been underway since October 2021.

“They’ve taken out a bunch of cows over the years, but the problem is that they haven’t gotten them all. So they just reproduce and the herd keeps growing,” said Todd Schulke, cofounder of the Center for Biological Diversity.

Along with the cows’ waste polluting waterways, their presence on the riverbed causes erosion.

Last year, he added, the Forest Service’s aerial gunners and on-the-ground round-up team each got about 65 cattle. This spring, during the aerial shooting, gunners got 19 cattle — accounting for a total of around 150 cattle removed by the Forest Service over the years. It’s unclear how many remain.

Schulke said that as the Gila Forest is relatively dry, the cattle have congregated closely to the river. Along with the cows’ waste polluting waterways, their presence on the riverbed causes erosion, impacting the endangered loach minnow and the spikedace, two small fish native to the Gila River Basin. Schulke added, “The cows eat the young trees, the shoots and the saplings … So they’re interrupting the long-term health of the forest part near the river by basically halting regeneration.”

In an attempt to get an accurate headcount and then exterminate the cattle, the “Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) flew the project area four times with thermal imagery and visual observations, as well as flying the periphery,” Wade Muehlhof, a national press officer from the Forest Service, said in an email. “Due to snow storms during the operational period, it was easy to track animals as they came out for grazing. No new tracks were observed in the fresh snowfall.”

Shad Sullivan, a rancher who sits on the board of R-CALF — a cattle industry lobbying group — shares the NMCGA’s concern, and said he has problems with aerial slaughter.

One of his main concerns, in addition to the issue of who may or may not own the cows, is that inaccurate shooting from above can lead to slow deaths. “When shooting cattle out of helicopters, it cannot be proven that they die,” he said. Sullivan heard reports of cows left injured but alive from the first round of shootings.

In an effort to offer alternatives to killing the cows, Patterson said the association made a directive that would work within the New Mexico livestock code, in which the neighboring allotment owners could go into the wilderness and gather those cattle. They would still have to present them to the livestock inspectors to make sure they didn’t belong to anybody. If they were deemed unowned, ranchers could then purchase those animals from New Mexico’s livestock board at a significantly reduced rate.

“When shooting cattle out of helicopters, it cannot be proven that they die.”

“Basically,” he said, “the reduced rate covered the cost of the inspections and the time. And then they could sell those cattle.” He said that this year, the association did have one of our neighboring allotment owners go to gather some of the cattle, which resulted in almost as many removed as the Forest Service shot.

That being said, on-the-ground gathering of the cattle is no easy task. In fact, that is one thing the two groups do agree on. Rounding up the cattle means at least a 15-mile trip on horseback, with no resources to rest the cattle along the way. This led to a high number of cattle deaths due to stress and self-injury, according to both the Forest Service and Patterson.

Still unable to come to an agreement on the right way to deal with the cows, the NMCGA is continuing with legal action to halt any future shootings. That said, having come out victorious in past lawsuits filed by the NMCGA and others opposed to the slaughter, the Forest Service plans to continue on its path of cattle removal.

“We need to do another survey to see how many remain on the ground, but 154 cattle have been removed since 2021 through ground and aerial operations. The Forest Service plans to move forward with monitoring to assess if any additional actions are needed in the future,” wrote Muehlhof.

And the NMCGA plans to keep fighting that path.

“Everybody thought, you know, that there were better ways to do this. Our state legislature, our governor even made a statement,” said Patterson. “And we should as a state, we should as locals, have a say. And it’s that simple. And that’s why we’re going forward with the lawsuit.”