Some countries have banned the tool, citing welfare concerns — but others argue e-collars save both canine and farm animal lives.

Nearly every day, dog trainer Jamie Penrith meets with dog owners whose pets have threatened or harmed sheep. “People come to me because they are desperate,” he said. “Either their dog has attacked, or they can see that their dog would attack.”

He teaches these dogs to leave sheep alone, using perhaps the most maligned tool in the dog training industry — the electronic collar, or e-collar. Through adjustable electric pulses administered via a handheld remote, the predatory pets learn that livestock are off the menu.

While the tool has been banned or heavily restricted in several countries due to welfare concerns — including Germany, Norway, and Sweden — some trainers argue that e-collars can prevent dangers to both livestock and dogs. Sheep farmers are even pushing back on existing bans, citing concerns for their animals. As more governments consider prohibiting the collars, debate is heating up over whether predatory instincts can be controlled without them.

Shocking Dogs to Protect Sheep

In the English countryside, where publicly accessible footpaths cross grazing lands, canine-bovine conflict is common. By one estimate, about 15,000 sheep are attacked by dogs every year across the UK — a number that may be growing, according to insurance data.

From speaking with owners, Penrith knows many attacks go unreported. “I would say you could probably quadruple that, at minimum, in terms of the actual attacks that do take place.” And livestock are not the only animals at risk — legally, farmers may shoot a pet that harasses their herd.

The conflict is common in Dartmoor National Park, where dogwalkers roam the rolling terrain alongside farmers grazing sheep, cattle, and ponies. Last year, the park’s livestock officer, Karla McKechnie, responded to 109 incidents of dog attacks on livestock, an increase from previous years. “We have a huge problem with out-of-control dogs,” she said.

In Wales, which enacted a ban on training with the collars in 2010, sheep farmers have called for a reversal. They argue that insurance data shows their animals suffer a higher rate of dog attacks than other parts of the UK. Adding to farmers’ concerns, a 2024 survey found that while a majority of dog owners let their dogs run free in the countryside, less than half of owners say their dogs come when called.

“We have a huge problem with out-of-control dogs.”

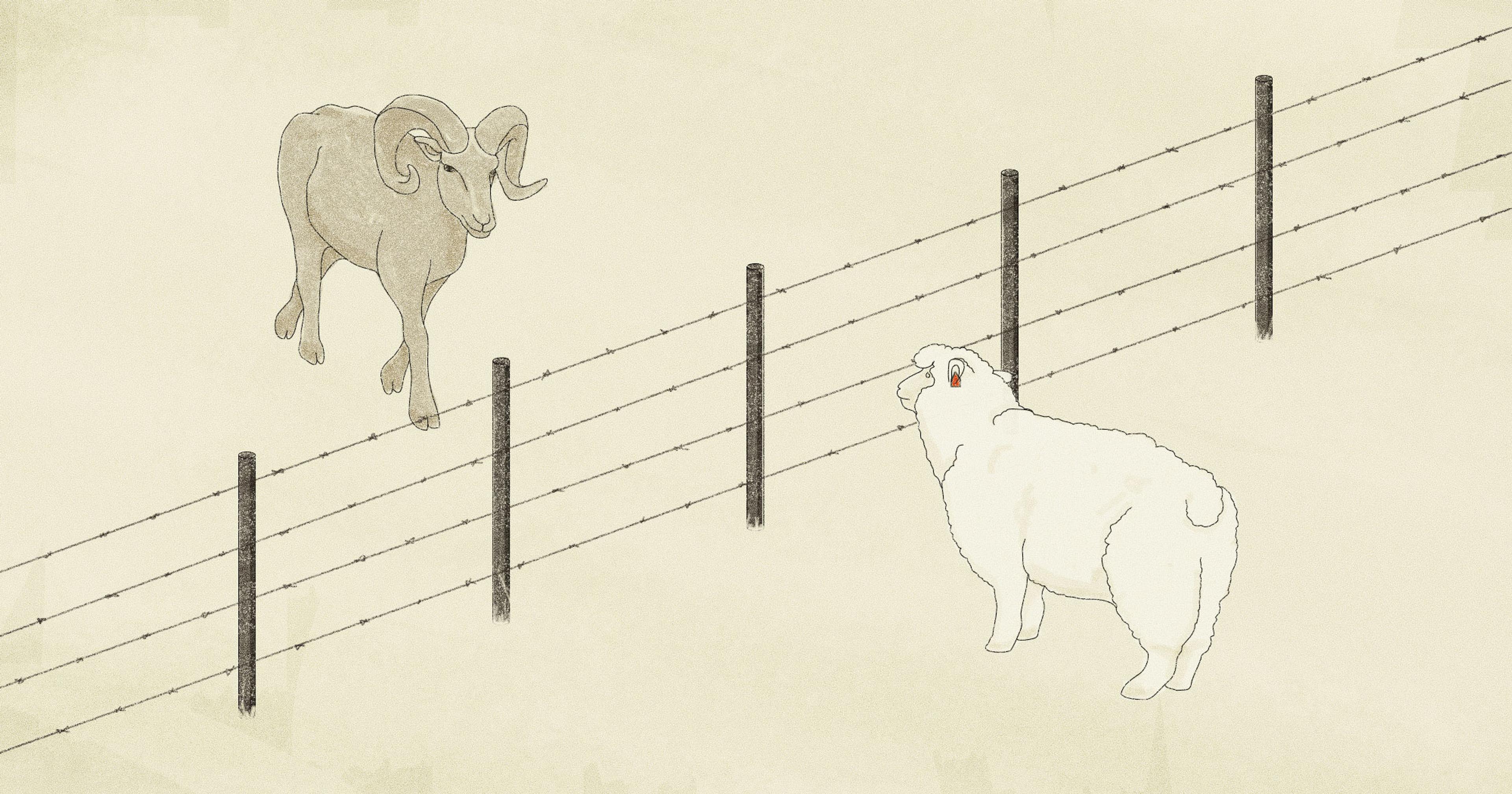

Years ago, Sarah N. (last name withheld for privacy concerns) of Devon, England, realized the risk of letting her dogs roam without training. On a walk through the woods, two of her dogs, Lola the terrier mix, and Fred the vizsla-pointer cross, charged a sheep down a steep bank and into a river. Her husband had to climb down the cliff, wade in the water and lift the sheep — shaken but uninjured — back onto shore.

After the incident, she hired Penrith. He first taught the dogs that following a verbal command to come back allows them to avoid the sensation coming from the collar. In a later session, the trainer brought the dogs near sheep in a controlled setting, delivering a pulse when their predatory impulse was piqued. The dogs learned two things: You must come back when called, and livestock must be left alone.

Usually after about three or four zaps, “the sheep becomes a stimulus that the dog thinks ‘do not approach under any circumstances, because it’s bad news for me,’” said Penrith. This negative association is intended to stop sheep attacks even when the dog’s handler isn’t present, which accounts for a large proportion of documented attacks — for example, when a dog escapes a yard.

After the training, Lola and Fred could safely run through the woods without bothering sheep. “It just gives them freedom,” Sarah said. “E-collars are a really good thing, used humanely with a trainer. ” (This reporter observed a similar outcome with her own dog, who now reliably responds to “come” even around squirrels and deer).

Electric Science

Electric shocks have a long history in behavioral research. Zaps can be timed precisely and delivered at calibrated intensity.

In dogs, findings dating back to the 1980s suggest that well-timed remote collar shocks — as part of a bigger training program — can curb unwanted behaviors. Still, other research has linked punitive training to worsening behavior in pets. The trouble is, protocols are inconsistent between studies. Many findings are based on owner observations reported in surveys, which begs questions like: Are certain tools causing problems, or are owners more likely to reach for those tools for problematic dogs?

The science on e-collars and livestock predation is sparse. In a 2001 study, researchers shocked 13 dogs when they came within two meters of the sheep. Tested a year later, their interest in sheep had tanked — only one dog stepped close enough to receive a zap. Owners of those dogs reported no negative behavior effects following the training.

Anamarie Johnson, an animal behaviorist working with U.S. rescue organizations, says there isn’t enough data on the consequences of e-collar training — both regarding predation as well as the emotional impact on dogs. That’s one reason why she studied stopping chasing in dogs as part of her PhD research at Arizona State University.

“The sheep becomes a stimulus that the dog thinks ‘do not approach under any circumstances, because it’s bad news for me.’”

For her study, published last year in the journal Animals, she selected dogs that chased a plastic lure moving rapidly through a motor-powered course. Then, the dogs were split into positive training and e-collar groups. The goal: Teach the word “banana” to mean “stop chasing.” (She chose a novel word that the dogs likely had no history with, unlike “come” or “stop.”)

In short training sessions, the word was paired with either a shock when the dog reached the moving lure, or, in the positive approach, the trainer said “banana” and dropped the dog’s favorite treat into a bowl while the lure machine was turned off. After the initial training, the dogs were tested to see how they responded to the banana cue when presented with a moving lure. While the e-collar-trained dogs were successful — most avoided chasing entirely or stopped when they heard “banana” — the food-reward group ignored the signal and chased the flying plastic. In a video behavior analysis of the training sessions, Johnson noted the e-collar dogs yelped when shocked but found few other signs of stress, though she added that the study didn’t provide insight into long-term impacts.

While some trainers embraced the findings (and others angrily criticized them), Johnson, who advises animal rescues on non-aversive handling and training methods, still thinks the collars are a risky tool in the hands of everyday dog owners. That said, “I don’t think anyone should be using my non-aversive protocol to try to stop [chasing] either,” she added, since it failed to stop dogs from going after the moving lure. Both training protocols were “super slimmed down” she added, and not something for owners to replicate — most real-world training takes longer, and is more complex, than can be fit into a three-day experiment.

(With more time, many e-collar trainers faced with a prey-chasing pup would teach an alternative behavior, such as coming back when called, and apply the stimulation for non-compliance. On the flip side, positive trainers might focus on getting many successful repetitions of “come” — rewarding heavily — until the behavior becomes near-reflexive.)

Avoiding Fragile Birds

While several countries have banned e-collars, at least one uses them in an official capacity to protect wildlife. New Zealand’s department of conservation, in partnership with nonprofit Save the Kiwi, organizes e-collar training to discourage dogs from approaching the flightless and fragile birds. Kiwi birds not only lack the ability to fly, they lack sternums — a hard nose nudge from a curious canine can be enough to crush their organs, said Emma Craig, dog specialist at Save the Kiwi.

The program started with hunting dogs in the 90s. Hunters use dogs to track their target: feral pigs. But those canines can also be drawn in by the kiwi’s strong musky scent. So, conservationists and trainers developed a program to teach dogs that kiwis are off-limits. In an outdoor training field, dog owners pretend to take their companion on a normal walk in the woods, but when the canine sniffs toward the kiwi decoy — either a real, dead kiwi or an artificial one, with added fresh scat for extra stink — the trainer shocks the dog via an e-collar, aiming for the lowest level needed to create an avoidance response.

Now, thousands of hunting, farming, and pet dogs are trained in New Zealand every year. While it’s not a guarantee against kiwi predation, Craig hears many stories from hunters — their dogs will suddenly move in a wide arc around an area, cautiously avoiding kiwi scent. Such unofficial reports as well some research suggests it provides extra security for the sensitive species, which is seeing a rebound in its numbers in some parts of the country.

A Welfare Worry or a Seatbelt?

From the spotty data available, Johnson and positive-reinforcement trainers remain unconvinced the tool is necessary and worry of welfare impacts, especially if owners can order the equipment with a single click online and no instruction. But, after facing intense pushback online for her research, she doubts other researchers will take up the cause of studying the behavior outcomes of using the training aids. The unwillingness to consider gaps in scientific understanding, said Johnson, is “a problem within the industry.”

Meanwhile, concerns about welfare continue to fuel proposals to limit use of the tool. In the United States, New Jersey and San Francisco regulators have considered bans. But, in a polarized dog training industry that seems to echo our current political climate, it’s unclear if dog professionals will come together on any guidance or regulation.

While acknowledging no training is fail-safe, Penrith argues the extra reliability of an e-collar is akin to a seatbelt — another layer of security for dangerous situations. Back in Dartmoor, McKechnie says that while she recommends leashing up pets near livestock, sometimes that’s not enough — leashes can break or slip out of hands. For dogs that are highly motivated to go after animals, McKechnie supports electric collar training to save the lives of both sheep and dogs. “Those dogs need to be trained,” she said.