A flesh-eating parasite, virtually eradicated from U.S. soil for 60 years, is ready for a comeback. What’ll it take to keep it at bay?

Horror fans are spoiled for choice when it comes to films about flesh-eating bugs. Giant irradiated ants with poison fangs threaten to extinct humankind in Them! Arachni-lobsters stagger out of The Mist to snap terrified Mainers in half while dog-size quasi-spiders (ok, not technically insects) lay eggs inside alive humans. Swarms of grasshoppers bloodily wing their way through men’s heads and torsos in Locusts: The 8th Plague.

For sheer dread, though, nothing beats a short film made by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1963, called Look Out for Screwworms. That’s because every brief, suspenseful scene in its two minute and 26 second run time is absolute fact: the scientists exposing screwworm larvae to “gamma rays from radioactive cobalt;” the clueless cows wandering fields where danger assuredly lurks; the rancher discovering maggots burrowed deep in the meat of his live sheep. Not seen but potentially more panic-inducing is the rare possibility of human death to what’s known as screwworm myiasis; a man in Costa Rica died from this last summer.

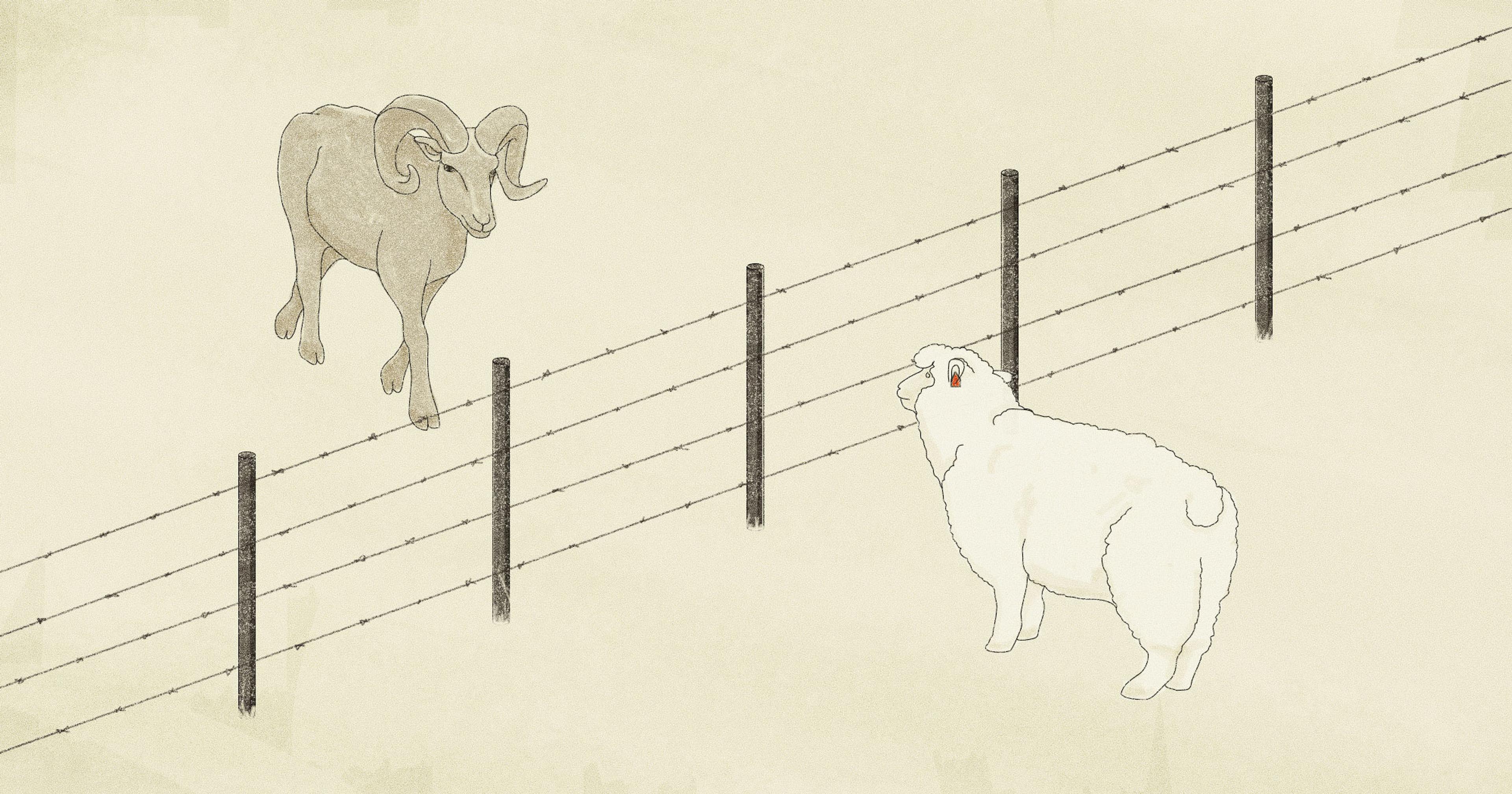

The New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) is a devastating pest — a species of blowfly — that’s native to the Americas. It was mostly eradicated from the U.S. in 1966 then beaten thousands of miles back south over the course of the next 30 years. However, it has managed to jump the jungle-y barrier afforded by Panama’s Darién Gap (where sterilization techniques have long been implemented to keep it at bay), possibly due to reduced jungle cover and more grazing livestock in the area. It’s made its way northward — from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador, Belize and Guatemala, and into Mexico, wreaking havoc along the way on all manner of livestock (and one deeply unfortunate human).

The advance of the screwworm, which is currently about 600 miles from the Mexico/Texas border, is making U.S. ranchers exceedingly nervous. Will defenses launched by university researchers, inspectors at USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), border-scouting “tick rider” cowboys, and scientists at fly-sterilizing facilities actually hold? That’s the question on every Southern rancher’s mind.

If “they were to come back like they were, it would put 90% of the cattle people out of business,” cattleman Jim Kearney, who helped his father in the “nasty” fight against the screwworm the last time around, told the Texas Standard. Treating screwworm infection is always disgusting business — the maggots have to be removed before the wound is cleaned and sutured — but back in Kearney’s father’s day antiseptic pine tar oil and insecticide smears added their noxious scents to the already-putrid smell of decaying flesh.

Philip Kaufman is an entomologist at Texas A&M and helped compile a new screwworm fact sheet that’s being distributed to ranchers. He isn’t prone to screwworm pessimism. “We are concerned but we are not in a crisis,” he told Offrange. “People are getting trained up and we’re gonna tackle this and solve it again.”

Also working in mammals’ favor (mammals are the preferred hosts, although birds will do in a pinch) is the fact that screwworms aren’t great at being parasites. Unlike other types of blowflies, these metallic-blue members of family Calliphoridae lay their eggs in live animals. They’re attracted by the smell of blood, from the wound left from a lamb’s umbilical cord, for example; or from castrating, branding, dehorning, and ear-tagging cattle, sheep, and goats. Horse ears can be munched raw by ticks, and among wild deer, shedding velvet from antlers is a siren call to screwworm moms to come on over and lay their eggs — up to 300 at a time. These hatch out spined maggots that anchor themselves into flesh, then proceed to eat their way through it, sometimes deep into muscle. If it’s deep enough the host animal cannot survive.

If “they were to come back like they were, it would put 90% of the cattle people out of business,”

“Normally with parasites, it’s not good to kill the host but inherently, by its host dying, that helps keep its numbers low,” Kaufman said. “If it were phenomenally good at its job we’d be overwhelmed with them.” Fire ants are powerful screwworm predators but unsurprisingly, no one is talking about dispersing more fire ants to eat the screwworms — although Kaufman expects native ant populations will help with the problem.

Still, there is bad news. The last time screwworms infested the American South, the population of Texas white-tailed deer was in the 10s of thousands. That population has since ballooned into the millions, according to Kaufman — in part, probably, because of the absence of screwworms to curtail their numbers. With more potential hosts around, eradicating screwworms will require a lot more effort should the pests make it over our border.

There’s been talk of using ivermectin to control screwworms in both wild and managed animals. But listening to Kaufman rattle off its drawbacks highlights the complexity of the task at hand. For starters, “Screwworm is not on the label for ivermectin,” he said, and FDA would have to be petitioned to change that. “They’re talking about adding ivermectin to [livestock] feed but how much do you give them? You don’t want to overdose them. You don’t want to under-dose. How long do you feed? Do you do two weeks on, two weeks off? A bobcat, it’s not going to eat corn [or pellets] out of a feeder, how do you control for that? What’s the withdrawal period going to be? Right now, it’s a 56-day withdrawal period for cattle” when used as an injected or pour-on dewormer.

“So you can’t butcher your cattle for 56 days. If you’re feeding wildlife, what does that look like for hunting season?” Studies, Kaufman said, would require “a lot of money, and they have to be done on every species you’re going to expose.”

Hopefully, it won’t come to this. Imports across the border of cattle, horses, and bison were halted this past May (as of this writing they’re being phased back in) and APHIS is working out how best to inspect and treat animals at the border and elsewhere, and how to quarantine regions or whole states if necessary.

“Reporting is the number one thing people can do. If you ignore this, that fly population is just going to get bigger and bigger ... this is a community issue.”

Fly sterilization techniques — male flies get zapped with radiation then dropped by plane over screwworm hotspots to mate with females that produce zero offspring — emerged in the 1950s and are still used, to great effect, today. A sterile-fly facility in Panama is still producing 100 million sterile flies for release per week, both an old J-06 strain that’s still effective, and a new one called PANCR-24 that was bred from flies in current outbreak areas. The U.S. is also funding updates to a Mexican sterilization facility and building a new one at an Air Force facility in Mission, Texas; the former should be online by summer of 2026.

Meanwhile, putting eyes on animals both wild and managed is the number one way to control for screwworms. To that end, USDA’s tick riders, who patrol the Rio Grande on horseback looking for animals carrying fever ticks, will have screwworms added to their portfolio of pests. Kaufman said ranchers must be on high alert, too: Check trail cams for animals “acting oddly, get out your binoculars and have a look.”

Changing livestock management might eventually be in order — forgoing dehorning, for example. And most crucially, inspecting animals often and thoroughly, and reporting any infestation to a veterinarian, even if it means the ranch could be quarantined. “Reporting is the number one thing people can do,” said Kaufman. “If you ignore this, that fly population is just going to get bigger and bigger and cause more of a problem for everybody else. This is a community issue.”