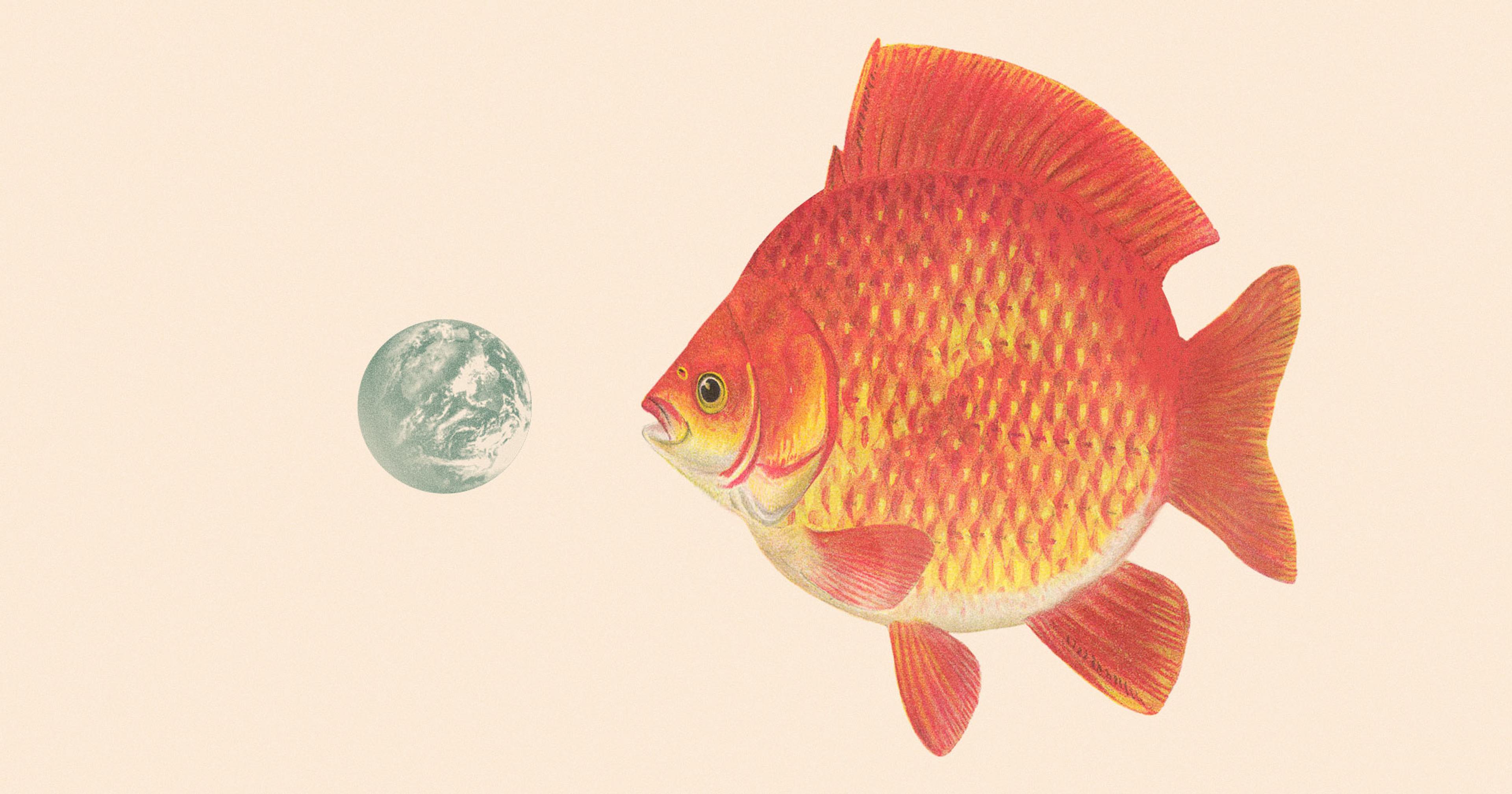

Releasing pet goldfish into waterways as an act of mercy can lead to ecological disaster.

My first pet was a goldfish named Sparkle. She was 25 cents at Petco, and the size of my pinky finger. My mother bought a tank and all of the accoutrements — pebbles, dark flakes of fish food, and a miniature net — for Sparkle and her inexpensive friends waiting in collection cups to enter their new home.

A couple hundred bucks and four days later, Sparkle was dead, floating on the turquoise skin of the tank’s surface. But another one of those specimens, a standard Comet goldfish, thrived for the next decade. When I went off to college, my father was in charge of caring for the nameless goldfish that was easily six inches wide and thick.

Now that I think about it, is he still out in the garage, swimming in that too-small tank? No one can be sure. It’s very likely that he passed away, but it’s also not unlikely that he was brought out to a beach on the Magothy River in a bucket and released by my dad to go live his best life.

But the impact of owners that want to be merciful and release their goldfish into a local water body is profound. The first consideration is size. A recently caught goldfish in France weighed more than 67 pounds. In 2023, goldfish caught in the Midwest were over a foot long. And, of course, there was Megalodon, a massive goldfish caught in March in Pennsylvania — and an instructive warning tale.

These goldfish grew that large for a reason: They’re adaptable, voracious eaters that breed like crazy. In recent years, their presence in the Great Lakes has caused researchers to reassess what part the creatures have to play in environmental decline. For example, Lake Ontario is known as one of the most degraded aquatic ecosystems in the bunch due to nearby industrial activity, but it’s also home to a colony of goldfish that spawn in a specific spot every year, and each one can live up to 25 years.

But what exactly makes goldfish so dangerous to local waterways? And are pet owners to blame?

The American Chameleon

Grant Lord, the owner of AboutGoldfish.com, is a walking encyclopedia on the namesake species. Within 30 seconds of a video call from New Zealand, I learned roughly 10 facts: There are over 100 varieties of goldfish, which are descendants of the Prussian carp, carassius gibelio, which is a part of the Cyprinidae family, which also includes the sleek, stylish koi fish.

It’s not uncommon for goldfish to live from 10 to 40 years, and for over 1,000 years, farmers in China selectively bred them, and started to see new, exciting colors emerge from the genetic pool. Before long, more varieties developed, which are dubbed fancies by goldfish insiders. They may have bloated cheeks, two tails, or elongated eyes, among other features.

Traders in boutique varieties can sell a fancy for $15 a pop. But goldfish as a whole are particularly unique, Lord says, because they quickly revert back to their ancestral aesthetic. “Their genes try to revert back,” said Lord. “That’s one of the reasons why you mainly see single-tail goldfish in waterways. A lot return to their orange color [from other varieties] because of birds of prey ... They’re very adaptable, and breed like rats.”

Jennifer Riddle, programs manager for the Invasive Species Action Network (ISAN), also spends a lot of her time thinking and talking about goldfish. ISAN is largely funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and though there have been announcements of all kinds of cuts in the federal government, they have not impacted ISAN.

“The barrier to entry for ownership is low. At the county fair, each kid gets a free goldfish.”

“I think [I talk about goldfish a lot] because many of us have owned one at one point in life,” she said. “The barrier to entry for ownership is low. At the county fair, each kid gets a free goldfish.”

But in our communal hearts and minds, when we hear the word goldfish, we think of the cracker or the Comet, the ubiquitous goldfish that children receive in a little bag at the county fair. The variety was bred around 1880 in Washington, D.C., in a few local ponds. It’s the most common type of goldfish that gets released in waterways, and can survive in a staggering range of temperatures and conditions. Fancies cannot.

Comets have very little economic value, and are bred as beta fish to feed turtles and large tropical fish. They’re the variety that goes into a little tank at home for a quarter, but that doesn’t limit what they can become.

The Question of Size

Though reputable resources say that goldfish are confined by their tank size and cannot grow to be large without more space, as an expert on the species, Lord isn’t completely sold on the theory.

“I’m doing research on this as we speak because it’s sort of a myth,” he said. “There are examples of stupidly large goldfish in small aquariums, and in other cases, there’s no growth [in a big space] ... So take that [idea] with a grain of salt.”

He argues that a goldfish’s size has much more to do with the mineralization of the water. When water is soft, which is excellent for laundry, that’s really bad for goldfish. Likewise, in the U.K. and the U.S. where there is a higher prevalence of hard water that runs through limestone, that’s an optimal environment for goldfish.

Beyond that, a significant misconception is that large goldfish are an anomaly.

“The Prussian carp can grow to 450 millimeters,” said Lord. “That’s just under half a meter. Goldfish grow to be large, especially the common Comets.”

Riddle concurs. Goldfish are hardy creatures and can survive in waters as long as they don’t freeze and do not exceed around 100 degrees Fahrenheit, so the majority of North American waterways are suitable habitat for them. If a pet owner dumps the contents of their aquarium into a river, it is more than likely that other species may die, but the goldfish will survive.

“I think part of it is sort of a numbers game,” she said. “The fact that they’re so common and so many people have had them means that they’ll be released.”

The Role of Pet Owners

As a goldfish enthusiast, Lord says that goldfish most definitely have personalities. Some are fearful, others are relaxed. They live a long time, and get to know the people who feed them. Lord says that if a stranger comes and stands beside him while he’s feeding the goldfish, they’ll swim to be closer to him, and be apprehensive of the stranger.

“Their memory is not three seconds. They remember stuff for months … They are quite intelligent.”

Yet even for all of Lord’s affection for goldfish, he is a staunch critic of pet owners who release their goldfish into the wild to live beyond a tank or personal pond.

“They should be shot for the ecological damage they’ve done,” he said. The problem is their very adaptability: Goldfish are not malicious like pike or catfish, but they eat whatever happens to float into their mouths, including a whole host of local aquatic plants. Years ago, Lord says that someone released numerous goldfish and koi in local waterways in New Zealand and has been disastrous for conservation managers to control.

“They’re very hard to get rid of,” he said. When a conservation body goes in to eradicate a goldfish population, Riddle says that it usually requires mechanical removal to selectively catch and cull the fish. There are also some chemical treatments that will kill them along with other non-target species. The economic burden of removing wild goldfish can fall to a state Fish and Wildlife service, or on a municipality. It just depends on where the water body is. A lake is a confined waterway, so eradicating released goldfish is difficult, but not impossible. In rivers, it’s a different story. They can never be completely cleared. A conservatory entity can work for years to chip away at the goldfish population, but one starry-eyed pet owner with a pair of tiny goldfish in a bucket can plunge the aquatic equilibrium back downhill.

But Riddle has a sympathetic view towards pet owners. When she talks to them about this issue, they get it. The dots connect, and she can see that when they let their pet go in the wild, it’s coming from a good place. They are often at a loss of what to do, she says, when they have to rehome a pet. Too often, pet stores sell animals without providing owners with information on the long-term commitments that come with it, or what to do if the owner is in a position where they need to rehome their animal. People get rid of pets for all types of reasons, like housing, a death, or even the cost to feed and maintain a pet’s environment — especially in this economy.

“You care for your pet. You’re releasing it into the wild where it might live a long, happy life … The biggest gap [...] comes from those selling or distributing pets.” Thus, part of the work in the future may be educating pet owners post-winning a carnival goldfish, but also getting buy-in from pet traders to be honest with their customers about what to do if they ever need to say goodbye to their pet.