What’s keeping the millions of lake trout in Lake Ontario from reproducing on their own? New tech is tackling a decades-old mystery.

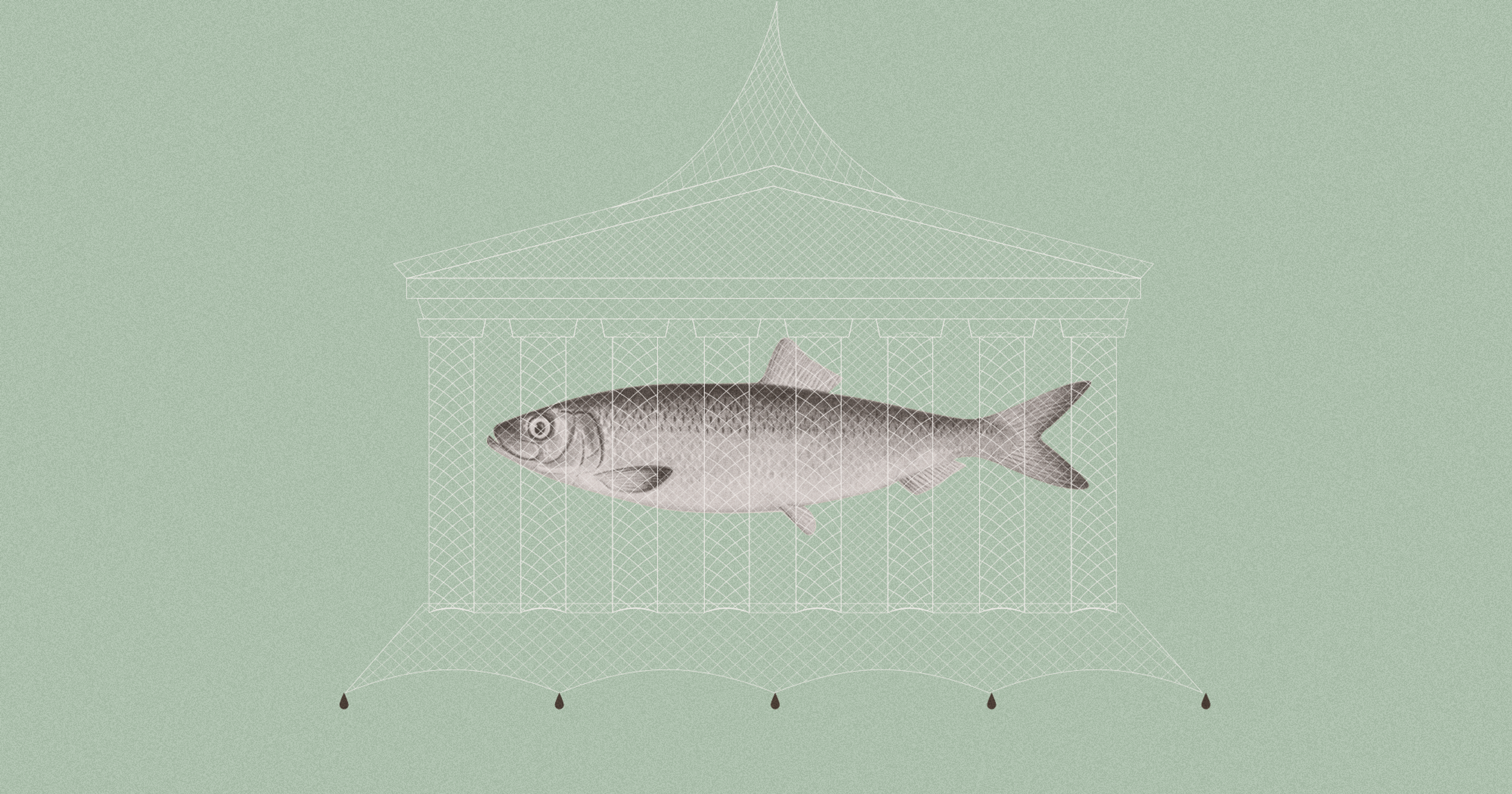

Each spring more than half a million lake trout are released into the frothy gray water of Lake Ontario. Raised 150 miles away in a Pennsylvania hatchery, each fish has been fitted with a metal nose clip that carries pertinent biographical information, including its genetic strain and when and where it was released. That means the next time someone — either a scientist or a sport angler — pulls the speckled, slate-colored creature from the water, they’ll also reel in a lot of important data. For more than 50 years, this data has said the same thing: Despite the billions of adult Salvelinus namaycush now cruising around Lake Ontario, almost none of them are reproducing.

Despite the trout’s abundance — remarkable given that overfishing essentially wiped them out by the 1950s — all that stocking has yet to yield a wild population. Scientists know the fish can reproduce naturally, but that something is getting in their way, a glitch in the ecosystem. For decades they’ve tried to identify and correct the glitch, battling one invasive species after another and addressing vitamin deficiencies that inhibit reproduction.

In short, none of it has worked. “We should be seeing natural reproduction,” said Stacy Furgal, a fish biologist and the Great Lakes fisheries and ecosystem health specialist at the New York Sea Grant, “and we’re just not.”

Last year, officials from five federal, provincial, and state agencies spread across the U.S. and Canada — working under the banner of the U.S.-Canada Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative (CSMI) — launched a massive 10-year study aimed at solving the 50-year-old mystery, establishing something of a trout surveillance state in Lake Ontario, which is bounded by the state of New York and the Canadian province of Ontario. They’ve caught and fitted hundreds of fish with telemetry tags, dropped receivers all over the 7,000-square-mile lake, and plunged cameras into the depths of its frigid water, hoping to reveal what’s keeping this keystone species from recolonizing its historic range.

Establishing a native population of lake trout would be an important step in repairing an ecosystem still reeling from a slew of century-old ecological harms. It would also bolster the health of the larger fishery, which provides a living for a small but diligent group of commercial producers like Tim McCormack.

“Ever since the trout have been gone, the fishery has been a shell of itself. It never rebounded from the shock of that loss,” said the 57-year-old third-generation fisher from Tipton, Ontario. “There used to be 40 families working out of the same harbor, now there’s just us. And it does stem from lake trout.”

For millennia, lake trout were an apex predator in Lake Ontario, providing sustenance and trade for the Anishinaabe tribes that made their homes along its shores. After a series of lopsided treaties stripped the Anishinaabe of their ancestral land in the region, countless European settlers set out in gill net tugs and trap net boats, creating one of the most productive freshwater fisheries in the world. By 1895, more than 12 million yards of gill nets were licensed in Ontario alone. During the early 20th century, lake trout fishers set lines with as many as 3,000 baited hooks per boat.

“Ever since the trout have been gone, the fishery has been a shell of itself. It never rebounded from the shock of that loss.”

While the lake teetered on brink of depletion, ecological catastrophe loomed on the horizon. The opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the 1950s connected Lake Ontario to the Atlantic Ocean, opening it up for international commerce — and making it the first stop for nearly 180 invasive species that hitched a ride on the so-called Highway H20, including the ravenous sea lamprey.

The arrival of the parasitic fish — a snakelike creature with a tooth-ridden mouth out of a horror movie — triggered an ecological and economic collapse the Great Lakes still haven’t fully recovered from. For lake trout in Lake Ontario, it was the last straw.

“Once lamprey got in there, they decimated the lake trout population,” said Larry Miller, who oversees the Allegheny National Fish Hatchery, birthplace of pretty much every lake trout swimming in Lake Ontario today.

In the 1970s, not long after the now-successful Sea Lamprey Control Program showed signs of promise, biologists began experimenting with genetic strains of lake trout from neighboring water bodies to launch a restocking program in Lake Ontario. But other obstacles stood in their way.

Thanks to a shortage of natural predators, populations of alewife, another invasive species, had exploded in the lakes. Whereas a 19th century lake trout feasted on a rich variety of fish, the restocked population were mostly chowing down on alewife. When researchers took them into the lab, they saw trout exhibiting some troubling symptoms: uncoordinated movements, stunted growth, and lethargy. In humans, these symptoms point to one thing: Vitamin B deficiency.

“The habitat is pretty degraded. Instead of big piles of rocks, you have rocks covered in invasive mussel shells which fill in places where eggs used to go and incubate.”

“Alewife is high in an enzyme called thiaminase, which causes a vitamin deficiency,” explained Furgal. “Vitamin B is crucial for reproduction.”

Furgal added that things have improved in recent years. Conservation agencies have begun stocking prey fish, which, along with another ascendent invasive species, the round gobi, are providing a more balanced diet to lake trout.

With the lamprey and alewife problems mostly addressed, researchers began to suspect that predation and reproduction health were not the glitch in the ecosystem after all — or at least not the only one.

Furgal says there was one last place to look: the fish’s spawning grounds. The new theory is that the trout are indeed reproducing, but “things are going wrong in the early life history stage, where eggs are being laid and hatched.” That means that getting to the bottom of this mystery requires journeying to the bottom of the lake, in the dark, cold crevasses where the fish deposit their eggs.

“Lake trout require rocky spawning substrates, places where their eggs can Plinko down through the rocks,” said Furgal. “They provide a cozy little spot and protection from predators or getting sloshed around by water.”

But even this remote part of the lake has not been immune from invasive species, she explained.

“The habitat is pretty degraded. Instead of big piles of rocks, you have rocks covered in invasive mussel shells which fill in places where eggs used to go and incubate.”

“We thought we knew the historical areas where they spawned. Well, we didn’t.”

The CSMI initiative aims to find the spawning habitat trout that are still using, assess it, and, if necessary, rehabilitate it. This could be done by cleaning the reefs of shells, or even dropping piles of rocks into the lake to create new spawning grounds.

But first, researchers have to find those spawning grounds — and it hasn’t been easy. “We thought we knew the historical areas where they spawned. Well, we didn’t,” said Miller.

“Since this is not the native strain, we don’t have good accounts of where these new guys are going to spawn, even the old ones — accounts from fisherman and community members — are loosey-goosey, from the days before GPS,” Furgal echoed.

To find current sites — or at least potential sites — the team used computer modeling to identify about 3,000 places in Lake Ontario that have the characteristics of good spawning habitat.

Then the researchers recruited some field assistants in their endeavor — the trout themselves. Last summer, using gill net, bottom trawlers, and even local sport fishing guides, they caught and implanted 400 lake trout with telemetry tags. For the next 10 years, biologists like Furgal will follow those tags as they ping to 500 receivers that are now scattered around the lake, providing vital information about where today’s lake trout are spawning. Scientists will be right behind them, visiting each and every site to collect data with underwater cameras.

“It looks like someday — maybe in my lifetime, but probably not — there could be a natural harvest.”

There’s a lot of work left to do, the fish biologist said, “but we’re getting a lot closer to the answers we’ve been after for decades.”

The tagging effort also marked a hopeful milestone: It was the first time a wild-produced lake trout was tagged in Lake Ontario. Scientists could identify the wild trout by its intact adipose fin, which are removed in hatchery fish to enable easy identification.

Tim McCormack, who said he’s also reeled in a handful of wild trout in the last few years, is feeling that hope. “It looks like someday — maybe in my lifetime, but probably not — there could be a natural harvest. It looks like it’s trending that way.”

Still, like every scientist and fisherman who’s been humbled by the whims of the mysterious Great Lakes, he’s quick not to get ahead of himself.

“Even then, we’ll have to be careful,” he said. “We can’t go out and go hog-wild on lake trout until that fish has gotten a grip.”