As U.S. farmers and ranchers get their hands on the technology, its labor-saving, climate-friendly benefits are becoming clear — and so are its shortcomings.

Tepusquet Canyon is one of the most picturesque spots in California’s Santa Barbara County, with sweeping views of the Pacific Ocean and the surrounding mountains. But on a 110-degree day last summer, Jenya Sarah Schnieder didn’t have time to admire the scenery.

She was there with Cuyama Lamb, the company she owns with her partner Jack Thrift Anderson, on a contract with the county. Schneider’s company had been hired to graze sheep on wild vegetation that increases the area’s high fire risk. To keep the sheep where they’d do the most good, her small team was painstakingly installing fencing on the area’s steep, treacherous slopes.

As the crew trekked up and down the chaparral-dotted mountainside, hauling rolls of electric netting and dodging poison oak, Schneider hit a breaking point. “I remember thinking, ‘This is not what sustainability looks like,’” she said. “Using grazing animals for fire fuel mitigation is wonderfully sustainable, but it’s not [sustainable] for the people providing the labor.”

This season, Schneider is awaiting a shipment of 100 GPS-enabled collars from Norwegian company Nofence, which launched its first U.S. virtual fencing pilot program this year. Instead of spending hours climbing hillsides to lay fencing, Schneider can create an invisible barrier with the flick of her finger on a screen. She’s reimagining how the tech will help Cuyama Lamb target areas too steep or thick with brush to fence on foot. “I could never walk through it, but I can draw a line on my iPad through it,” she said.

The concept of virtual fencing — controlling the movements of animals without the use of a physical barrier — dates back to the 1970s. In fact, the technology used to keep pet dogs in yards without physical fencing came first, when Invisible Fence founder Richard Peck patented that system in 1973 (though a cable had to be buried around the perimeter of the property). In 1987, researchers at Montana State University first experimented with virtual fencing and cattle, using Invisible Fence gear to show proof of concept.

But it took decades for GPS functionality, wearable tech, and our understanding of animal behavior — pushed forward by experts like USDA researcher and “cattle whisperer” Dean Anderson — to catch up with the need for real-time land management that virtual fencing provides. Only in the past few years have these systems started to become commercially available to farmers and ranchers in the U.S.

As producers — from small-scale dairies to cattle ranchers to targeted grazing operations like Schneider’s — get their hands on virtual fencing, the benefits are coming into focus: saving labor on farms, protecting natural lands, maintaining higher-quality pasture, and sequestering carbon. But so are the current challenges to the technology’s widespread adoption.

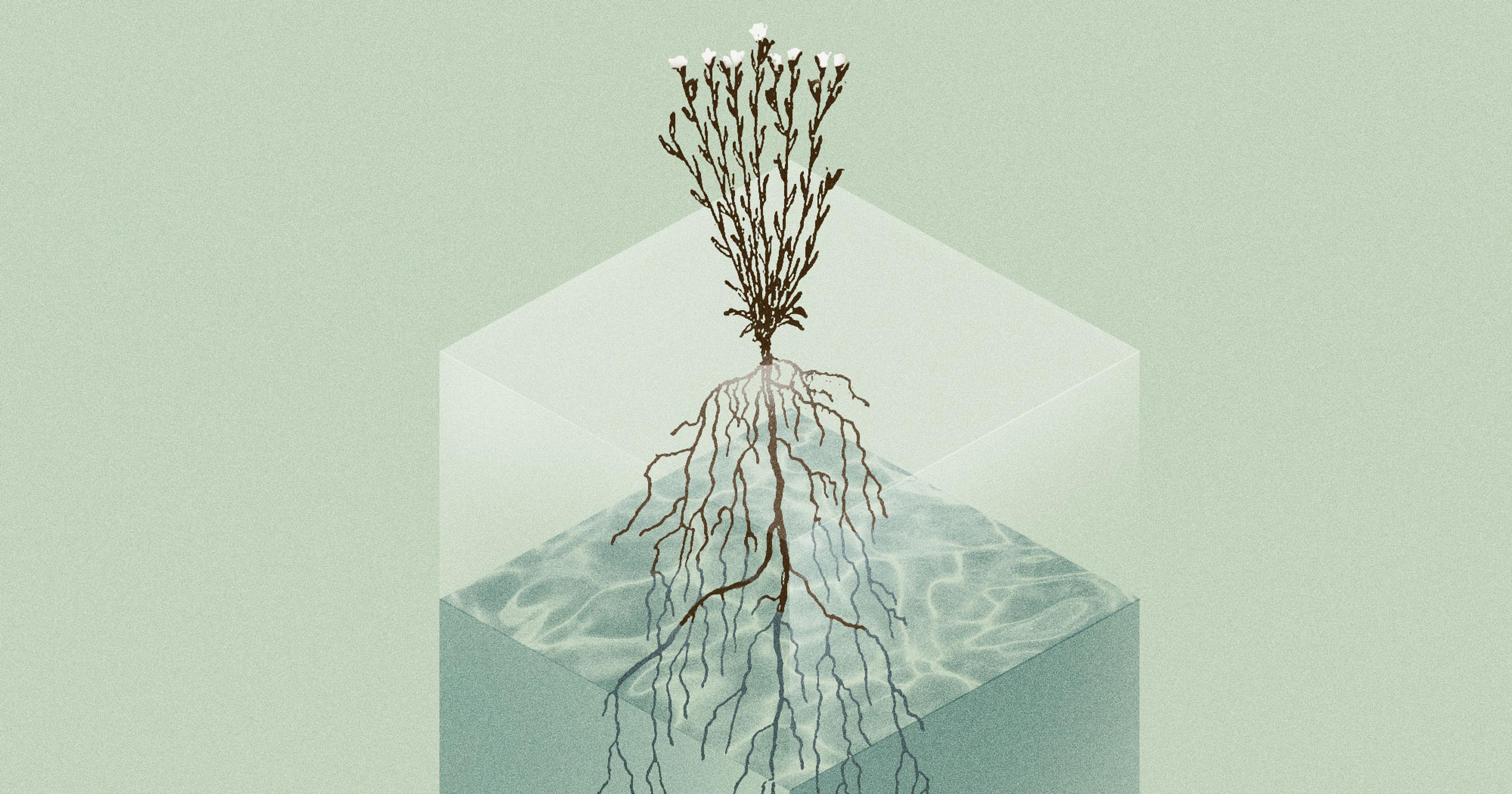

A System Advances

Livestock in virtual fencing systems wear collars fitted with GPS trackers and solar-powered rechargeable batteries. As an animal approaches the virtual boundary, its collar emits a high-pitched audio cue, which gets louder as the animal gets closer. If the animal reaches the boundary, the collar delivers a mild electric shock similar to bumping a snout against electric fencing — which quickly teaches the animal to heed the audio cue. When it’s time to move the animals to a new area, a farmer can simply redraw the barrier on a computer or mobile device.

“It’s going to be a huge savings for us,” said goat farmer and cheesemaker Molly Kroiz, who owns Georges Mill Farm in northern Virginia with her husband Sam. After reaching out to Nofence a few years ago, hers is one of 45 farms in its U.S. pilot program; the company also operates in Spain, the U.K., and its native Norway. Sam estimates the system is already saving 20 labor hours each week and helping the couple manage pastures more effectively.

“It’s allowing us to be a little more agile, too,” she said. “We can move the goats more quickly through places where we might have had to leave them longer before, just because of how long it would take to put the fence up.”

“Pastoralists have so much knowledge about the range and how to manage it. It’s intriguing to find how they will use them best.”

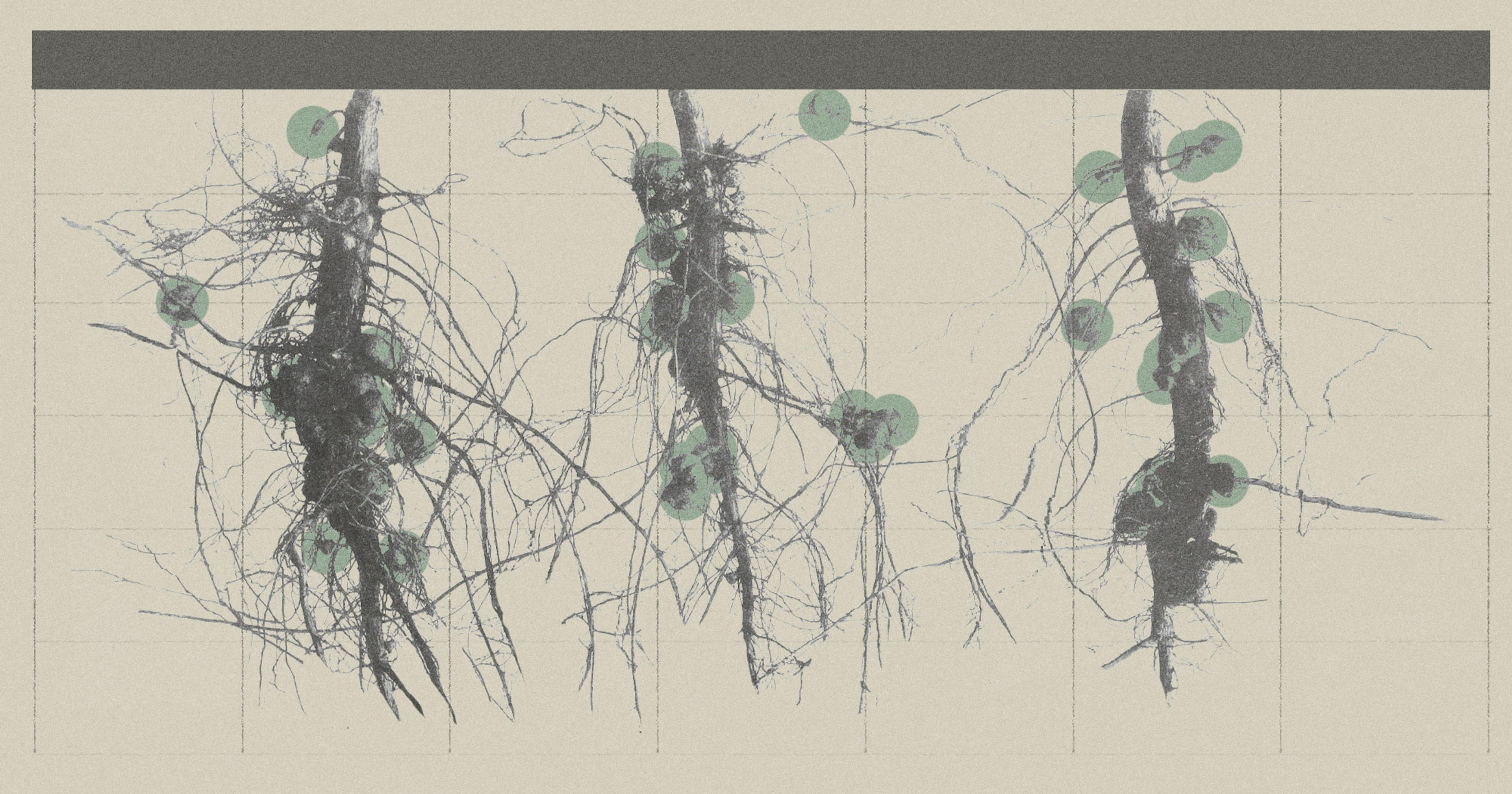

Virtual fencing isn’t a perfect solution — the troublemakers in Kroiz’s herd will still sometimes slip through — but unlike physical fences, the technology doesn’t deter animals from coming back inside the boundary after they escape. And because GPS locations can be somewhat imprecise, the virtual “line” is actually more of a 15-foot zone — so in certain areas, like along roadways or the path leading into the barn, the couple still sets up temporary fencing.

As GPS and solar technology continue to improve, companies have hurried to bring a commercial product market. Nofence, founded in 2011, claims to be the first to make virtual fencing available to farmers; they’re the only one on the market currently offering collars sized for small ruminants like sheep and goats — not just cows. New Zealand-based fencing giant Gallagher recently acquired its eShepherd virtual fencing technology from an Australian startup, and in 2022 Merck Animal health purchased Vence, a U.S.-based startup offering collars to farms and ranches with 500-plus head of cattle.

While the concept is basically the same, Vence and eShepherd require the purchase of a base station to communicate between the collars and the farmer’s device. The base station can drive up startup costs and must be moved when animals are relocated significant distances; Nofence relies only on cellular networks. Another U.S. startup, Corral, which is geared toward small farms and ranches raising beef cattle, will send collars with a directional audio feature to its first customers later this year.

Addressing the Imperfections

Availability is one challenge to adopting virtual fencing’s benefits on a wider scale. Eli Mack, who raises beef cattle, sheep, and poultry on pasture outside Pittsburgh, works as a product specialist for Kencove Farm Fence Supplies, offering consults to fellow grazers on holistic pasture management. He sees a lot of potential in virtual fencing — once more producers can get their hands on it.

“There are a lot of products out there that work great for open pasture applications, but the more somebody gets into ecological grazing or silvopasture, where we’re trying to establish trees and keep the animals off of them, that’s where a lot of those products kind of meet their limitations,” he said.

“Our concentration right now is getting collars to farmers,” said Allysse Sorenson, who works in U.S. sales for Nofence and runs her own goat-powered targeted grazing company in Wisconsin. “We’ve been approached with different ideas for integrating other things into the collar and the app itself, but there’s still so many people that are just trying to get the functionality that it has today.”

Virtual fencing also doesn’t deter predators the way an electric fence can.

Another challenge is cellular dead zones, which can cause animals to disappear on a farmer’s tracking app until they come back into range (though the boundary remains intact). Corral is adopting a satellite-based system next year to ensure producers can track their animals even in areas with poor service.

Virtual fencing also doesn’t deter predators the way an electric fence can, though livestock are able to flee more easily than they would with a physical barrier — and systems like Nofence can alert a farmer to the herd fleeing. Plus, many farmers already use dogs or permanent fencing around their property line to protect animals. Rather than supplant physical fences outright, virtual fencing replaces temporary farm fencing and allows the creation of barriers in places where rough terrain, conservation aims, or sheer distance would make any kind of barrier impossible.

There’s also the issue of animal welfare. The collars, which have been designed with animal behavior in mind, rely on audio cues first to teach animals to stay away, then deliver a deterrent shock similar to that of physical electric fencing. Studies have shown that collars used in virtual fencing systems don’t impact animal welfare any more than contact with a physical fence does. Still, Nofence had to get a special dispensation to use the tech in places like the UK where shock collars for animals are banned outright.

And then there’s the cost. Collars for cattle run $250 to $300 each, and most companies charge an annual subscription fee of around $40 to $50 per animal. If the system involves a base station, that equipment can start at $10,000. That puts the technology out of reach of many producers, though some, including Sorensen and Schneider, received grant funds to cover upfront costs.

“We’re trying to democratize access to the technology.”

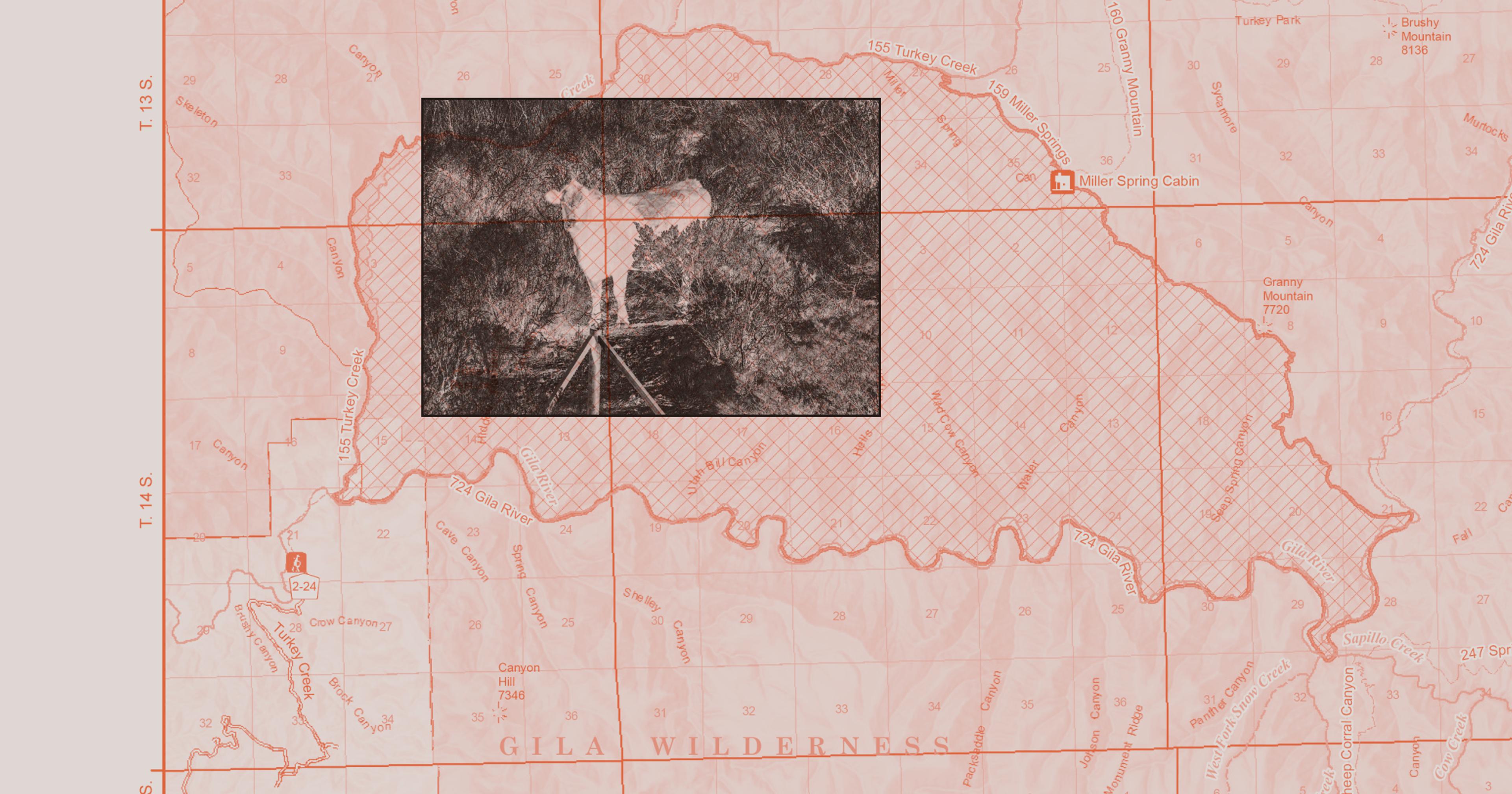

That inaccessibility is a problem Mario Herrero, professor of sustainable food systems and global change at Cornell University’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, is hoping to mitigate. He and his team will use a new $9.9 million grant from the Bezos Earth Fund to create and distribute their own low-cost virtual fencing tech to pastoralists in middle- and lower-income countries over the next five years.

“We’re talking about 20 dollars in materials cost per collar for virtually the same thing” as what’s on the market, Herrero said. “We’re trying to democratize access to the technology.” The project will also release open-source plans to build the collars; Herrero plans to design a system that works well with audio cues only — no electric shock.

Better range management can support the implementation of silvopasture by allowing ranchers and herders to virtually fence off tender new plantings from hungry ruminants. Keeping animals off overgrazed areas can help rehabilitate degraded grasslands: when vegetation has a chance to rest and regrow, the result is higher-quality feed, which can reduce methane emissions by as much as 17 percent without impacting production. “We’re not coming only from the climate perspective,” Herrero said. “We want farmers to see the benefits of increased productivity and increased incomes and nutrition if possible.”

Herrero is particularly excited about gathering data and feedback and using it to learn and improve their system, which anyone in the world will be able to build on. “Pastoralists have so much knowledge about the range and how to manage it. It’s really intriguing to find out how they will use them best,” he said. “I think we would learn a hell of a lot.”