California 4-H launched a series of drone camps this summer, preparing teens for farming’s future.

When you think of 4-H, do you picture images of prized calves, giant zucchinis, and delicious pies? This summer, one 4-H program is taking to the skies so that teens can learn about using drone technology in farming.

This program comes at a time when the U.S. agricultural drone market is experiencing rapid growth. According to one forecast by Grand View Research, the segment is expected to grow from $506 million in 2024 to more than $1.7 billion by 2030. Benefits include reduced water, pesticide, and fertilizer costs by targeting only those areas in fields where they are needed. One study in Brazil showed that using drones for spraying used just 10 liters per hectare, compared with 250 liters for tractor application.

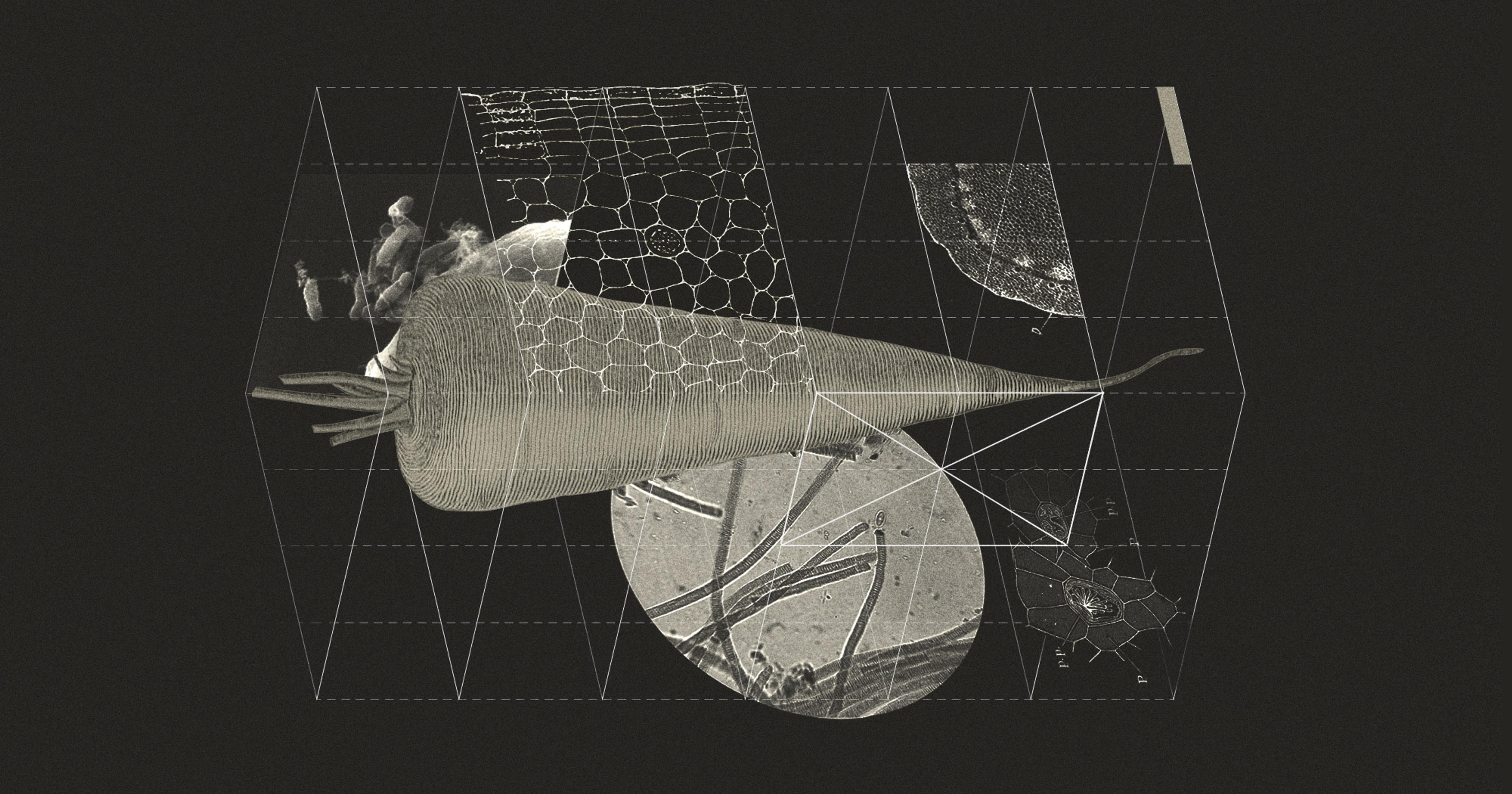

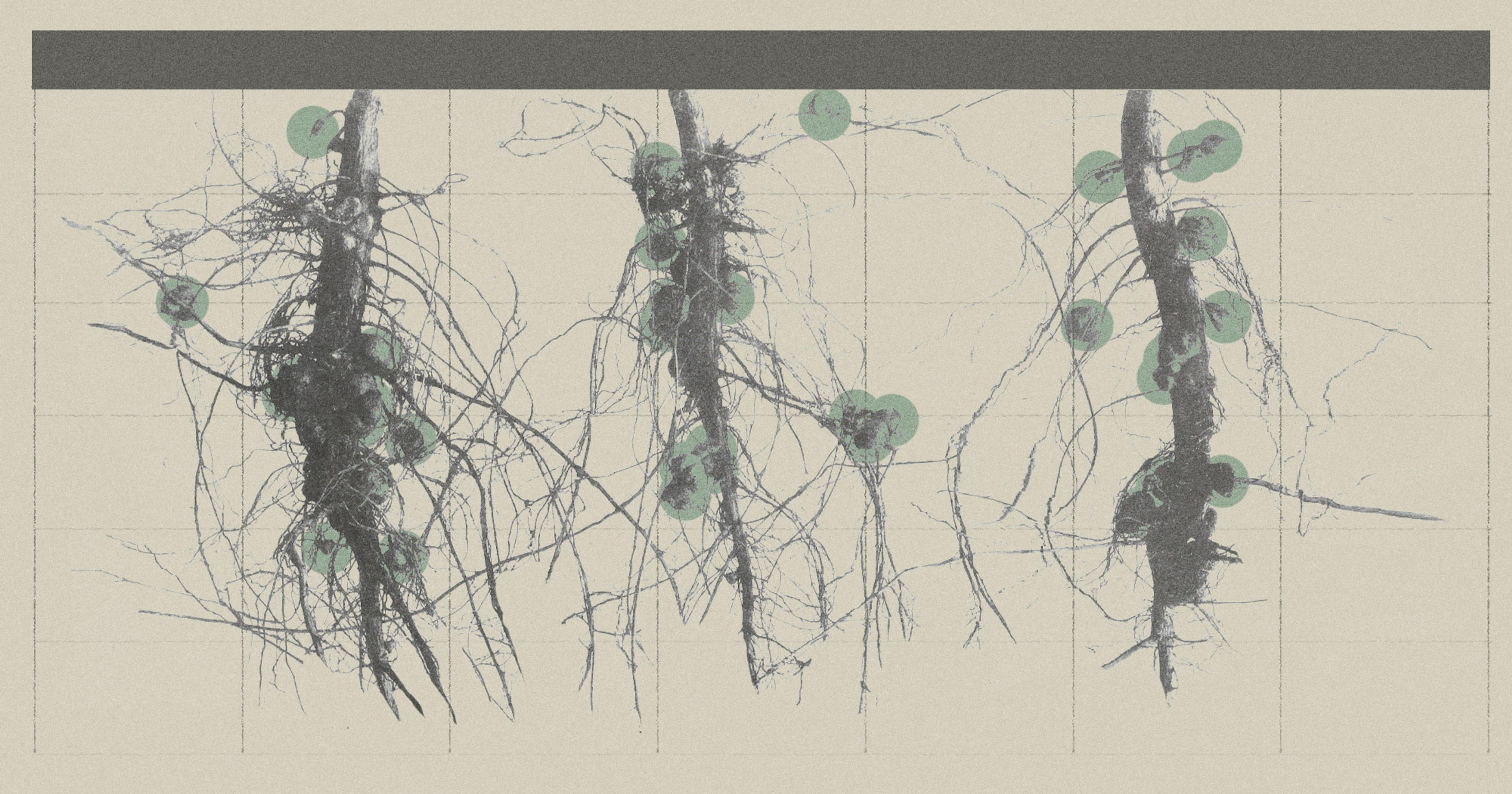

Data from drones can also result in higher crop yields through early detection and intervention of issues that could affect plant growth. And drones make far more efficient use of farmworker time and effort, as the devices can conduct field inspections faster and in greater detail than a human can.

Flying a drone for commercial use requires a FAA Part 107 Remote Pilot Certificate, which is available to operators 16 years or older after completing a written test (which costs $175). This qualifies the user to operate a drone that weighs less than 55 pounds that is flown during daylight hours no higher than 400 feet above the ground while maintaining visual line of sight (VLOS) with the drone. (Enforcement has been sparse, with only 27 civil actions taken between October 2022 and June 2024, but fines can be up to $75,000 per violation.) Steven M. Worker, 4-H youth development advisor with UC Agriculture and Natural Resources, is “excited to have a draft curriculum and to be pilot testing it at our youth drone camps.” He expects that the program will help campers ultimately attain their 107 licenses.

The majority of ag drones are currently focused on monitoring operations, according to Sean Hogan, drone program coordinator with the University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. These include using spectral image analysis to identify pest infestations, irrigation needs, and areas requiring fertilizer. Other applications include monitoring livestock herds.

Regulations hinder some uses of unmanned aircraft in agriculture. For example, the VLOS requirement typically limits the operational distance to about 2,500 feet, depending on terrain and weather conditions. Some applications are permitted under specific waivers, such as clearance for a pilot to operate a swarm of up to three drones at a time which can greatly increase the area that can be covered. Waivers can also be obtained for drone spraying applications for pest control or fertilization, which might also include a waiver for nighttime operations when conditions might be more favorable.

Hogan looks toward a future when the use of ag drones will be expanded. “Removing the VLOS restrictions and even permitting the use of autonomous drones” would make drones far more useful, he said, especially for larger farms with a lot of acreage.

In the meantime, California 4-H is hosting a series of week-long camps this summer to teach teens how to fly drones and use them to gather data to improve farming practices.

The camp curriculum is based on a modified version of training courses for adults that have been held over the past nine years, according to Hogan.

“Flying the drone accounts for only about 7% of the total time” that it takes to complete a camp project.

The participants will learn to fly drones safely, as well as gather and process the data from those flights. As it turns out, flight time is just a small part of using drones in agriculture. “Flying the drone accounts for only about 7% of the total time” that it takes to complete a project, said Hogan. The participants will also learn to use GIS (Geographic Information System) mapping software in conjunction with the aerial images and other data gathered from their flights.

The California 4-H camps will give some teens a head start in this new field. According to Hogan, “A single drone operator can cover about 200 acres in a day. Agricultural drone pilot is an emerging career opportunity.” The camp experience covers a range of STEM components, which are essential for agricultural applications. Hogan points out that “there is a shortage of people who have all the required skill sets” for drone projects.

The camps are part of a broader program called AFA2, which stands for “Ag from Above for All.” This three-year program is designed to engage youth aged 13 to 18 in the food and agriculture industries, through hands-on experiences. It is funded by a $750,000 grant from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA). The program appears to be working, based on the positive response to the drone camp opportunities.

Mekhai is one of the teens who has registered for one of this summer’s camp sessions. He already had some experience flying his brother’s drone. “I’m eager to learn more about how drones are used in agriculture,” he said. “As someone who is currently raising a dairy goat and a market pig through 4-H, I’m passionate about livestock and farming. I’m also interested in exploring how to combine my interests in agriculture, livestock, and technology.”

These three camps are just the first step. Worker said that, “The goal is to finalize and disseminate the curriculum to other state 4-H programs and other youth programs. We have funds to copy edit, graphic design, and disseminate the curriculum.” Drone camp: coming to a state near you.