Microbial products made for improving crop growth, also known as biologicals, are a billion-dollar industry, but the promises touted by these products might be too good to be true.

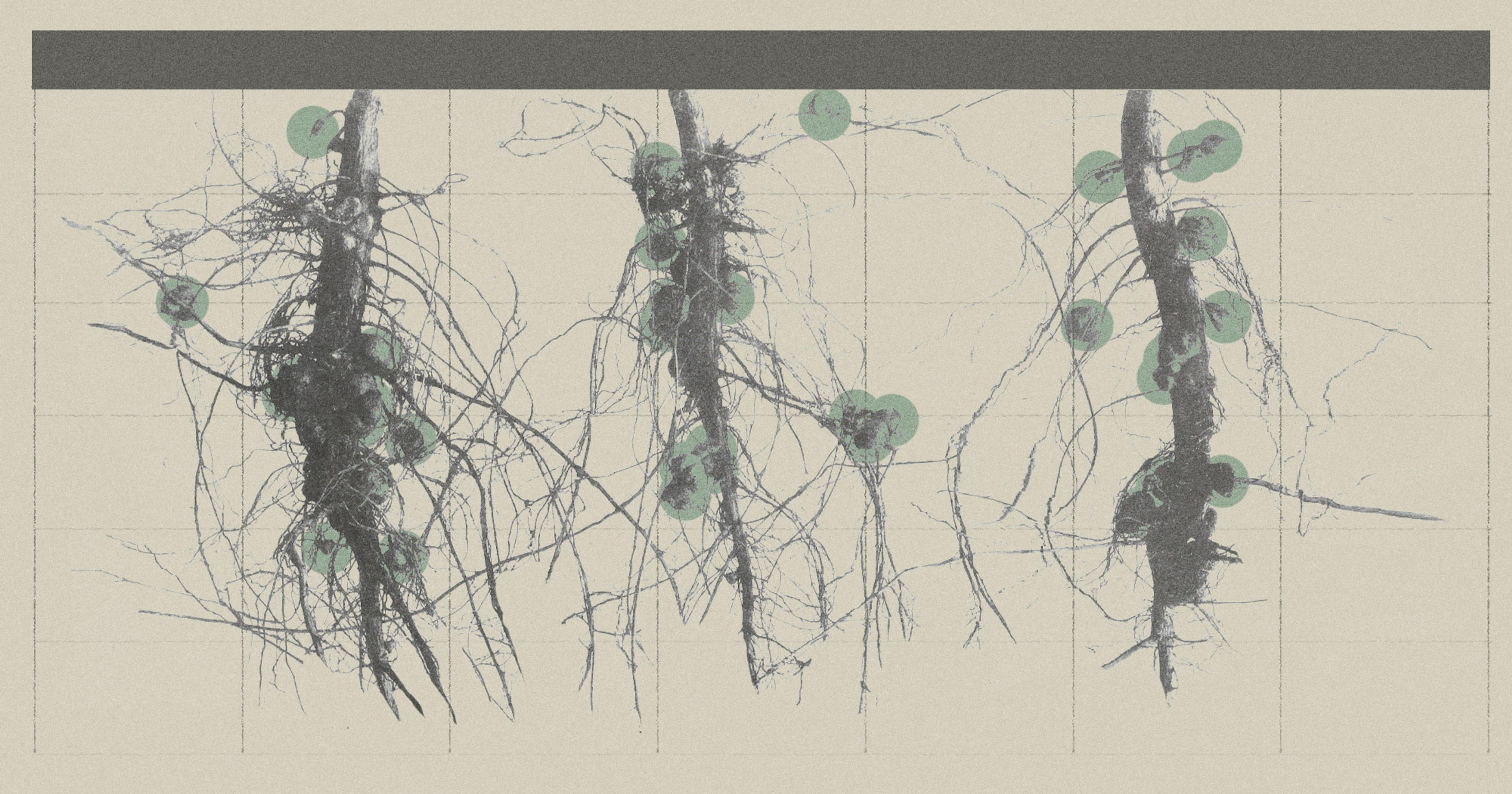

A hundred miles west of the North Carolina coast, Adrian Locklear farms 4000 acres of soybeans; he swears by using microbial inoculants on his seeds every year. “Whenever we dig our plants up, we’re looking at our roots, there’s just so much more nodulation starting on the soybeans so much earlier, and they look so much more healthier, than if we did not inoculate,” he said.

Locklear farms in the coastal plains of southeastern North Carolina, which are known for their sandy well-draining soils, deposited there millions of years ago when the sea level was much higher. This soil has made it really challenging for Locklear to grow soybeans.

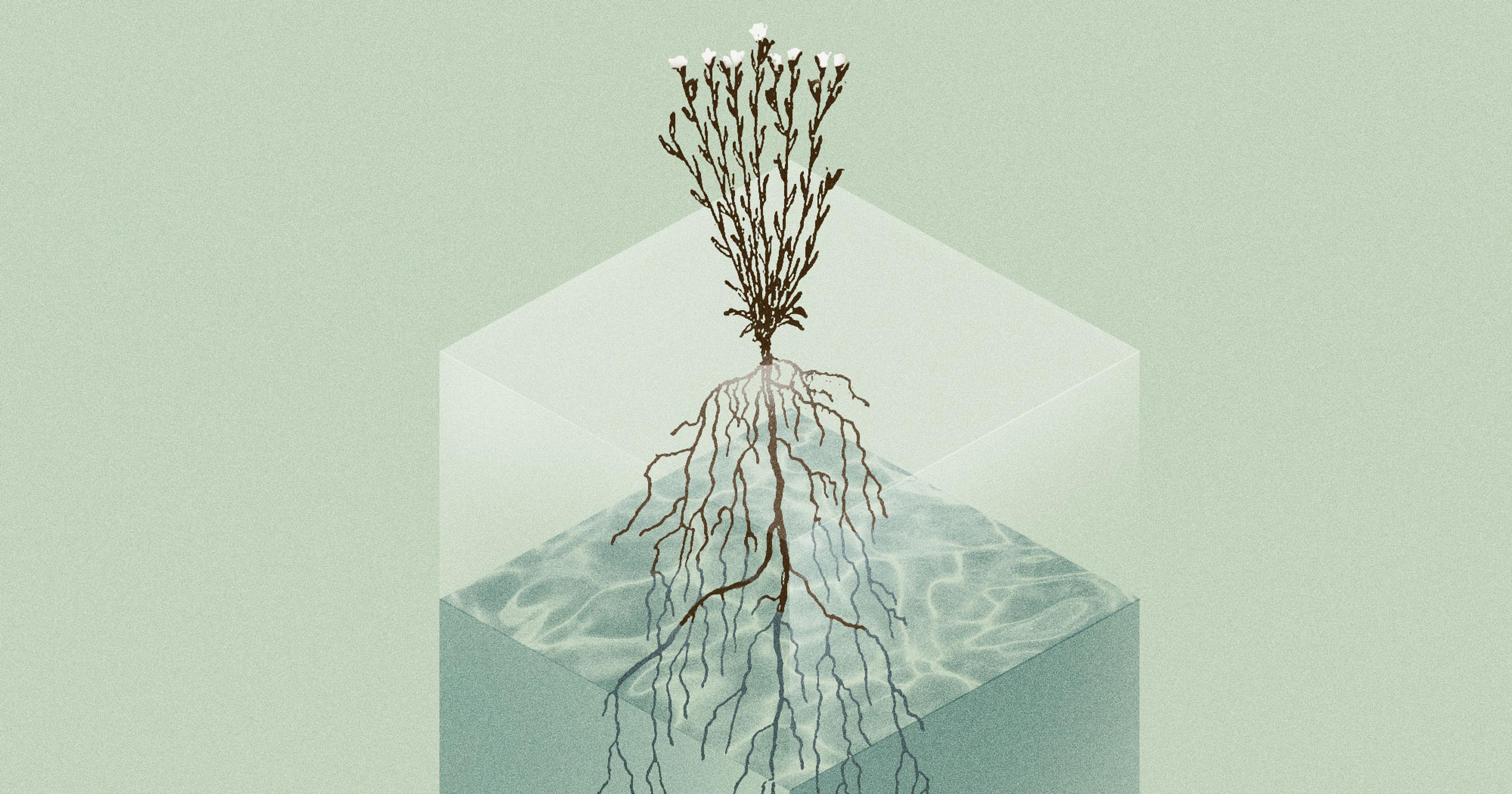

The nodules on the roots of soybean are essential to their nutrient content. Nodules are root growths that house nitrogen-fixing bacteria from the soil and in return the soybean receives nitrogen from the bacteria. However, these bacteria occur in extremely low quantities or are completely absent from sandy soils.

“A lot of times you dug plants up and you looked at the nodules, there wasn’t a lot of nodules on the plants. I could see it visually in the plant. They were a pale green and they didn’t quite have the vigor that some of the other plants had,” said Locklear.

Now that he uses seed inoculants he’s seen a vast improvement in yield. “I really think on a large scale, I think we’ve seen maybe a two-bushel increase.”

These types of seed inoculants are part of a growing market of biologicals — products containing microbes or biologically derived compounds that benefit crops — and are expected to grow into a $31.84 billion industry by 2029, according to Markets and Markets.

But do these products live up to the hype?

“The Wild West”

Biologicals are divided into four major groups: biopesticides, pathogen controls, biofertilizers, and biostimulants (which improve growth overall). There are also a variety of application techniques including a powder coated on the seed, a liquid applied in furrow, or sprayed directly onto plants. Some seeds are even sold pre-coated in an inoculant.

The mechanisms by which these products work are as varied as their application methods. Biofertilizers and biostimulants directly improve plant health by increasing nutrient uptake, root growth, yield, and vigor by forming partnerships with different microbes present in an inoculant.

Some types of biologicals, such as biopesticides, have been around since the 1930s. However, the reliability of newly developed biofertilizers and biostimulants has been met with some skepticism due to variability in success.

Piran Cargeeg has been working at the agrochemical company BASF for 35 years, focused on research and development of seed and soil biotechnologies, including biologicals. Cargeeg affirms that when biologicals first hit the market it was the Wild West of products and claims.

“I would agree that numerous early pioneering biologicals lacked performance consistency. Typically, for small and mid-range enterprises at this time — the drive to market and profitability were important for survival. Performance sometimes ‘lacked luster’ — generally as a result of reduced understanding of topic and technology, as well as not setting the correct expectations.” Cargeeg believes that in the rush to be a part of the expanding biologicals market, some smaller companies pushed products that had only been minimally tested and not marketed correctly, creating distrust among farmers.

In the rush to be a part of the expanding biologicals market, companies pushed products that had only been minimally tested and not marketed correctly, creating distrust among farmers.

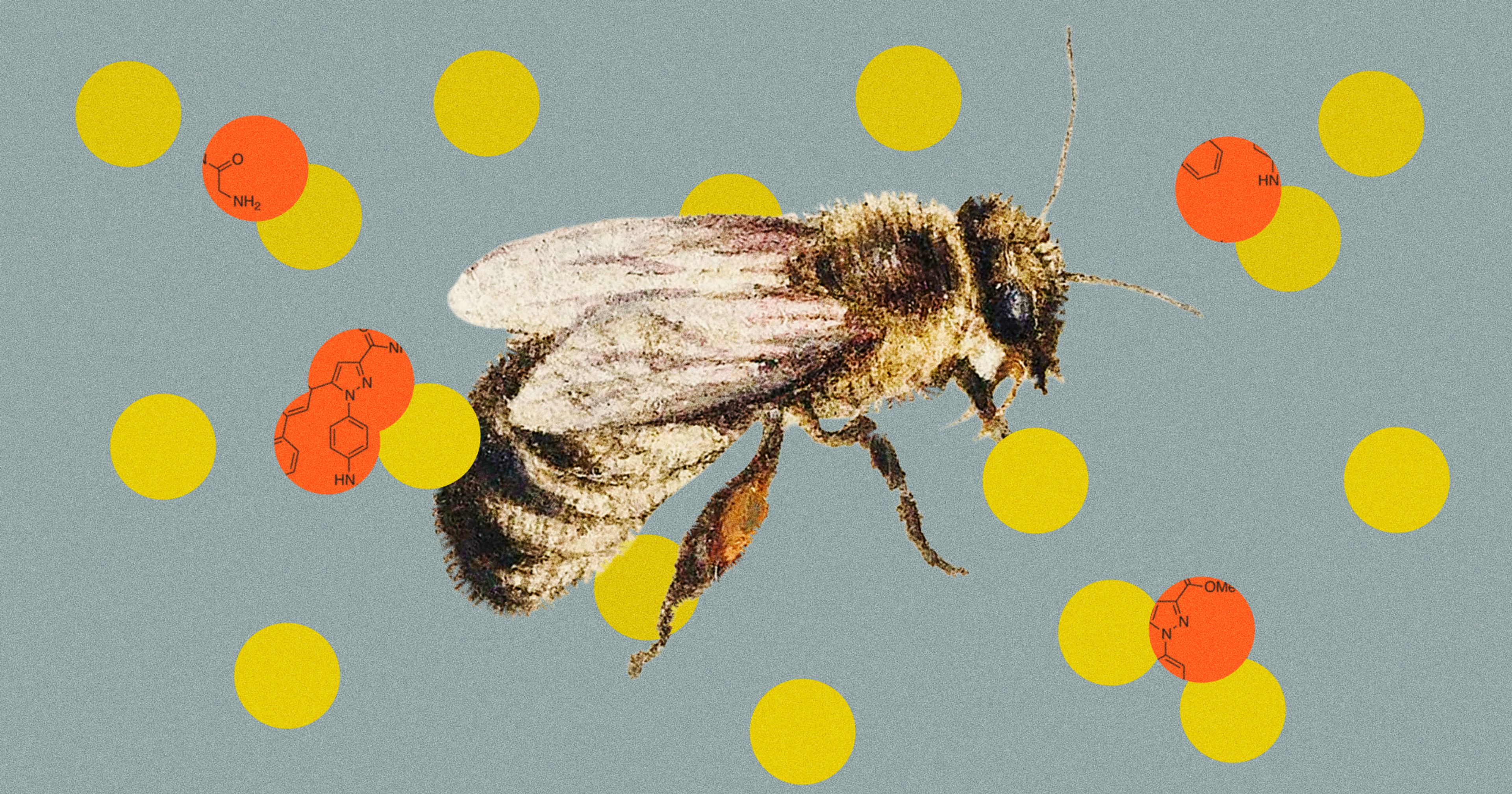

But even with current improvements to biologicals technology, some are still concerned about their efficacy and consistency. Mallory Choudoir is an assistant professor and extension specialist at North Carolina State University who studies soil-microbe interactions in agriculture. “There’s this expanding market of biostimulants. And it’s just this immense commercial market and there’s very little regulation.”

In 2024, she tested the effects of four seed biostimulants on soybeans in the field. The claims of these products seemed too good to be true. One of the products in the study claimed up to a 10x return on investment and improved yield. However, Choudoir found no difference in yield between treated and untreated soybean. She reasons that perhaps nutrient-rich soil and efficient plant breeding have something to do with the biostimulants’ failure to perform. “In the field, we are evaluating these products in high-yield environments. And for the most part, we’ve bred plant varieties to perform well under high-nutrient conditions. So, there’s not really a need to establish relationships with microbes.”

Despite these lackluster results, she is hopeful that microbes could serve as an amendment for current fertilizer use, especially for more sustainable soil practices.

“I think biologicals will continue to improve. I don’t see this as this dichotomy between biologicals and chemistry, but I think there’s the opportunity to specifically reduce synthetic fertilizer inputs.”

Do Your Own Research

On the other hand, Adrian Locklear is glad that using biological inoculants has been worth his investment.

“When you talk about inoculants on the farm, that’s one of the cheapest things that you can put out to the plant. Anytime I can get a two-bushel increase on a $4-an-acre investment, I think I’m doing pretty good.”

Despite his personal success, Locklear suggests that other farmers should use biologicals on a case-by-case basis. “I mean, I know all regions of the country are different, different soil types, different microbes in your soil. But I think we have to look at it on a farm-by-farm basis and see how different soil types work. It’s like anything else; it might not work every single year on every single farm. That’s why I think you need to do your own research and study.”

Introducing biologicals is not only an additional monetary cost to growers but also another cost in the time growers need to research these innovative technologies. Cargeeg from BASF suggests that growers should consider all local data available before committing to a product.

“For any product, I would recommend to the grower to ask for field data generated in your local area across at least two growing seasons.”

“Anytime I can get a two-bushel increase on a $4-an-acre investment, I think I’m doing pretty good.”

Choudoir agrees. “Locally relevant field data is important. Some companies provide more information on the type of microbe, maybe where that microbe was sourced from, the specific mechanism of that microbe, whether that’s phosphorus solubilizing or nitrogen fixing. So those more specific modes of action can be a helpful way to at least include [biologicals] and evaluate. But certainly, it’s a cost.” Companies that not only market the benefits but also the mechanism by which these products work would allow farmers to make informed decisions based on the nutrient needs of their crops.

But even if biological companies provide product data, many farmers just don’t have the time to do the research needed to choose the right biological product. The Certified Biostimulant Program provides a solution to this problem. The program certifies there is data to support the claims made for a product, based on United States biostimulant industry guidelines. However this program is still in its infancy and only has 10 products registered.

The current best resource for farmers is to bring their questions about biologicals to their local extension office as Locklear did before he decided to use inoculants. “I talked to my local extension agent here in the county and about treating seed with some inoculants. And I guess we both agreed in our sanity and souls that that’d be a good practice for us to start doing.”

Looking to the Future

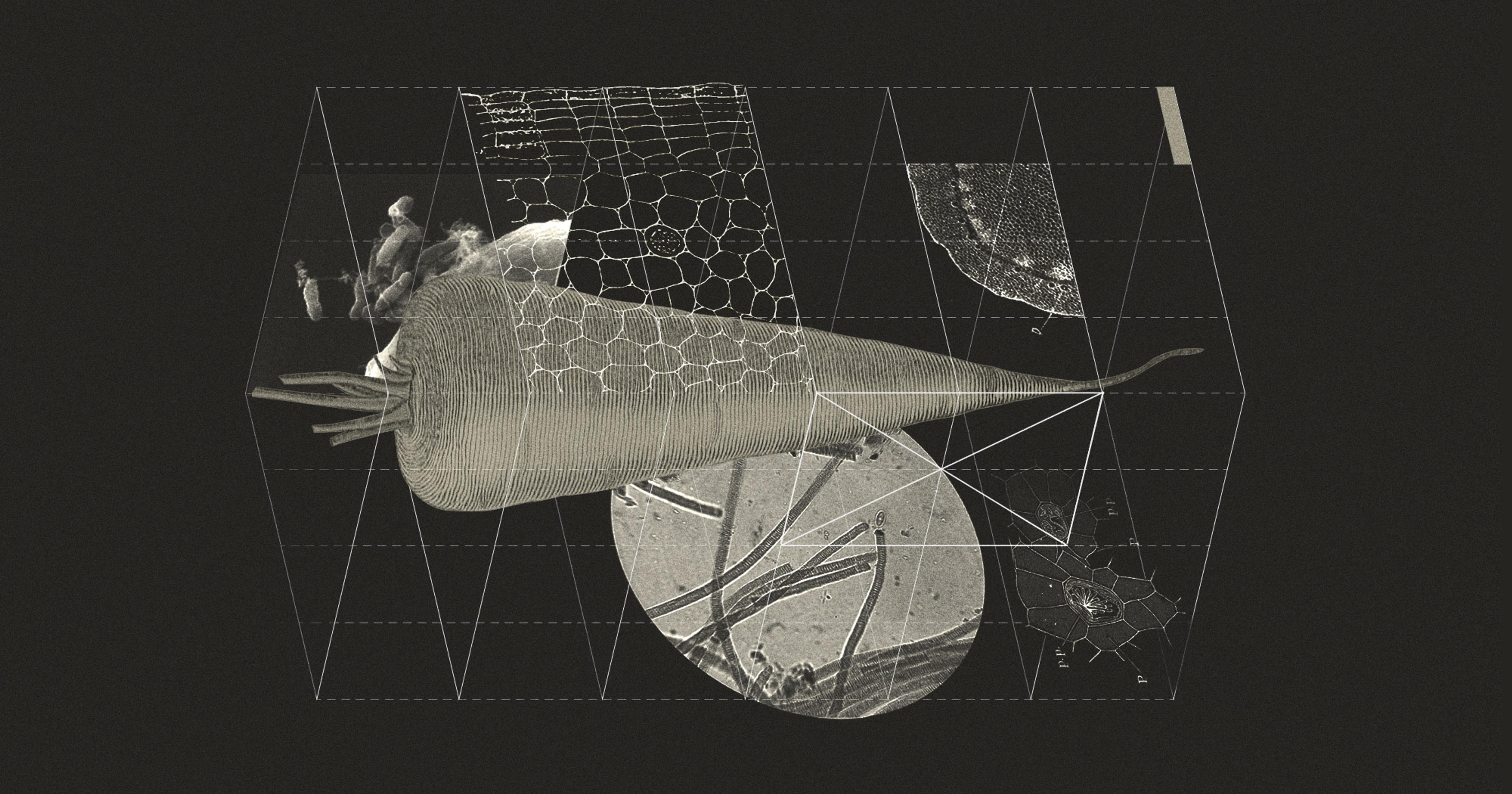

Consumers now not only demand that their food be healthy but also that the practices used to make those crops are sustainable. In a 2025 global consumer survey by PWC management they found 44% of consumers would be willing to pay more for food to support “actions taken to improve the health of the land and the environment.” Advocates argue that biologicals can provide a safer alternative to synthetic chemicals in terms of the effects on human health and soil health. Choudoir hopes as the possible benefits of biologicals increases, that biotechnology companies begin to target other aspects of sustainability and soil health.

“I think targeting all those processes that contribute to soil health, whether that’s nutrient cycling and reduced nutrient loss, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, potentially some carbon soil aggregation. There’s a lot of opportunities there.”

Locklear just hopes for an improvement to ease of use in inoculant technology overall.

“Putting it on the seed is pretty easy, but it’s a little messy trying to get it coated evenly. I would probably like to see more liquid, so I can do more and firmer products. A lot of times with the coating stuff, you got to mix it really well to get a good even coat.”

Meanwhile Cargeeg is optimistic that biologicals can one day become just another part of what a farmer uses to improve yield.

“Biologicals are increasingly finding their place as a tool in the agronomic toolbox. Definitely not silver bullets, but if used judiciously with the correct expectation setting, the right biologicals will provide value to the grower.”