Fake seeds can cost farmers up to two-thirds of their yields, putting global food security at risk. A team at MIT has devised an anti-counterfeiting system using microscopic silk labels.

In 2018, a coalition of Black farmers from the Memphis area filed a lawsuit against Stine Seed, the largest independent seed producer in the world. The claims were straightforward: Farmers who attended a Memphis farm conference the year before were sold more than $100,000 in counterfeit soybean seeds. Plaintiffs alleged that they purchased what were supposed to be high-yield, certified Stine soybean seeds which were swapped out for inferior seeds before delivery.

“We were anticipating thoroughbreds, and we got sold a donkey,“ said one of the plaintiffs, David Allen Hall Sr., at a press conference announcing the suit. (Stine denied all wrongdoing.)

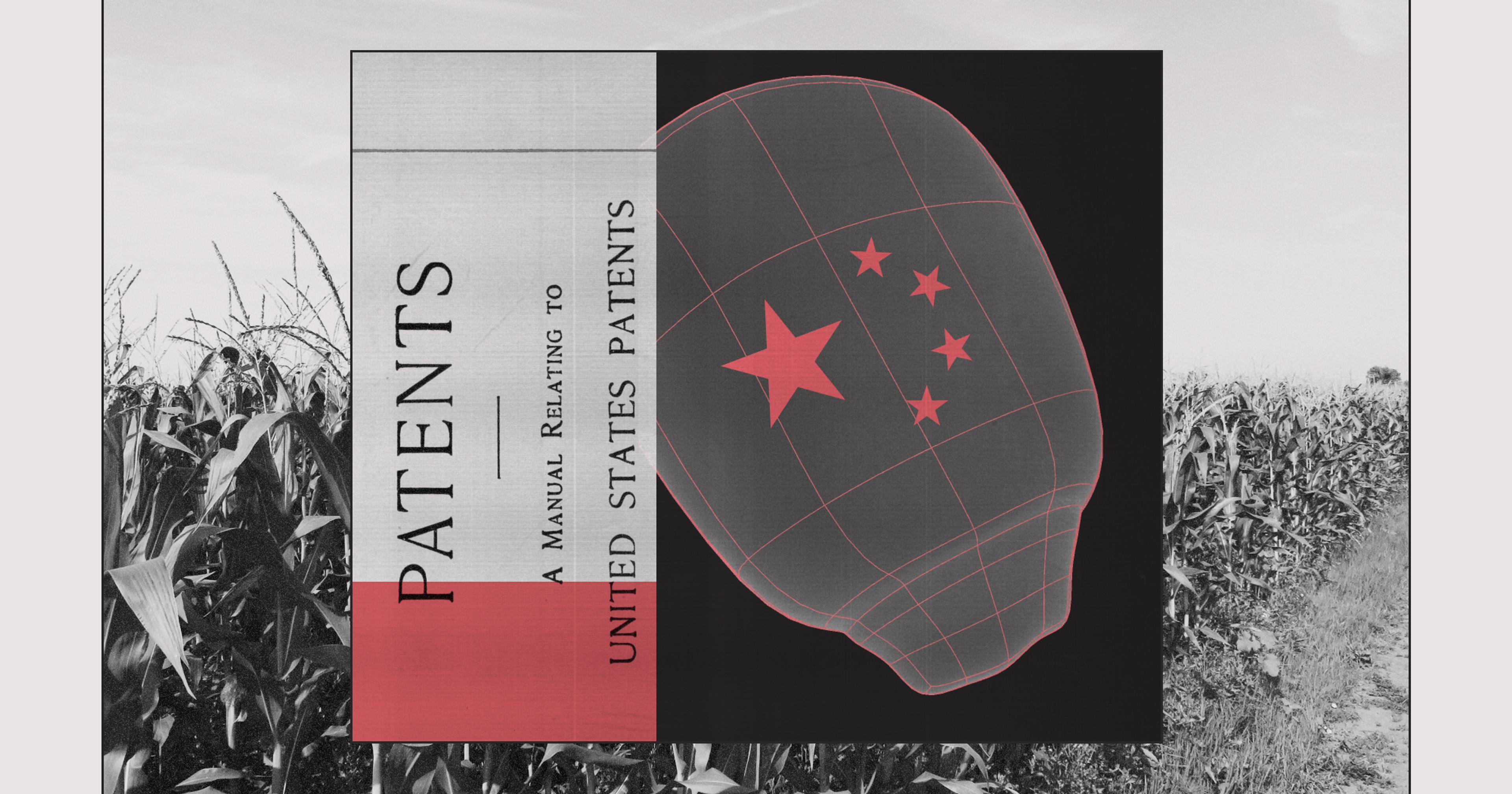

Seeds are big business, at an estimated market size of $61.2 billion in 2021 expected to grow to well over $100 billion by 2030, according to analysis from Zion Market Research. With commodity crops like corn and soy, there is a range of quality in the market, from top-shelf certified seeds like the ones allegedly on offer in Memphis, to low-quality “bin-run” seeds that produce lower yields and can bear disease risks.

And, as with any lucrative consumer good, there’s a significant difference in the profit margin between high- and low-quality seeds. Large agribusiness companies like Bayer spend significant resources combating counterfeits to ensure their trademarked products are the real deal.

The fake Stine seeds were a bit of an anomaly — here in the U.S., counterfeit seeds on the agricultural market are less of an issue, especially for commodity crops like corn and soy. Federal regulations are so strict, and major seed manufacturers so litigious and protective of their IP, that the odds of commercial seed buyers getting duped are much slimmer. But in many parts of the world — particularly in countries where agriculture products are more likely to be purchased via informal markets — a robust trade in fraudulent seeds persists.

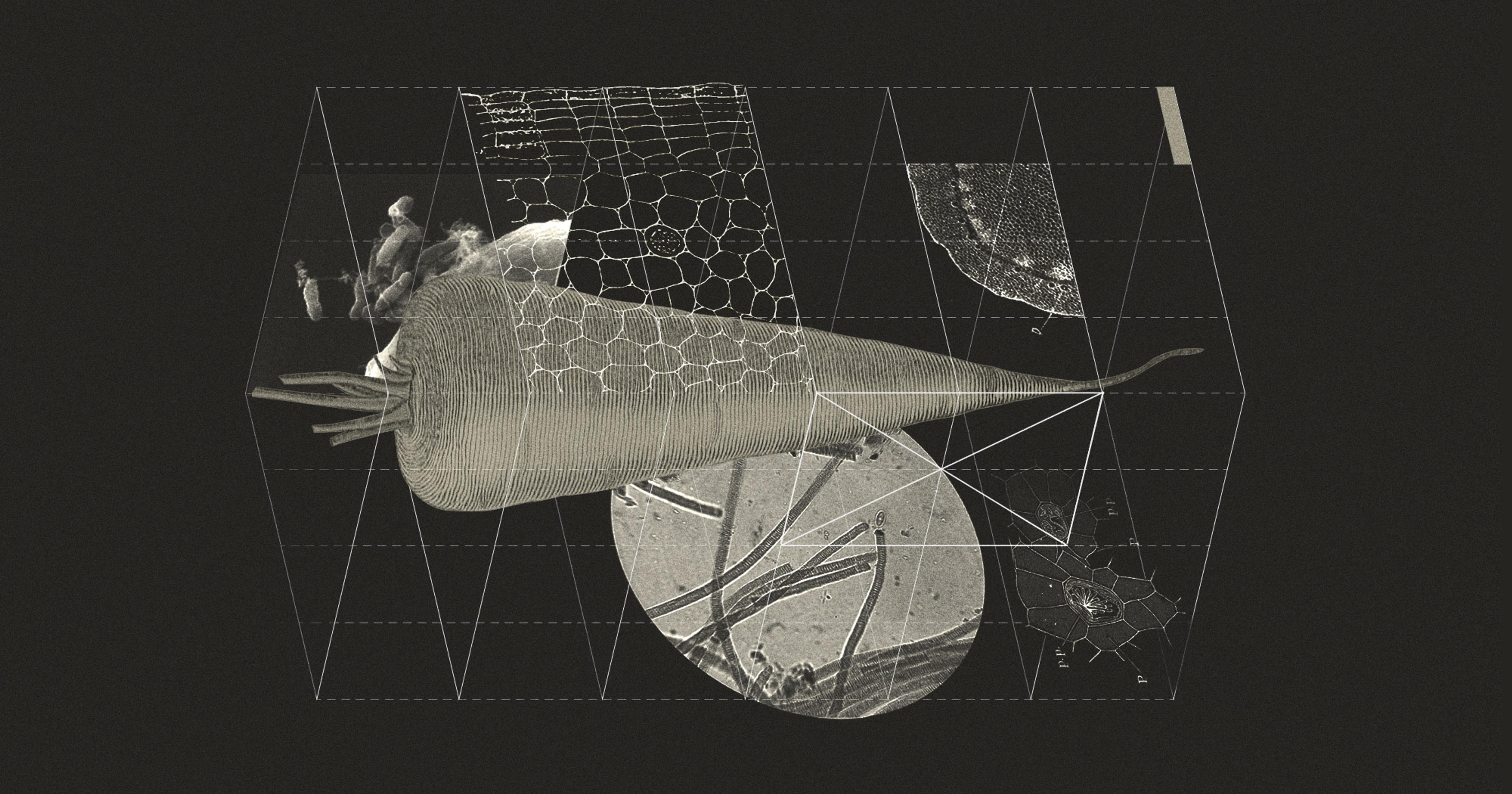

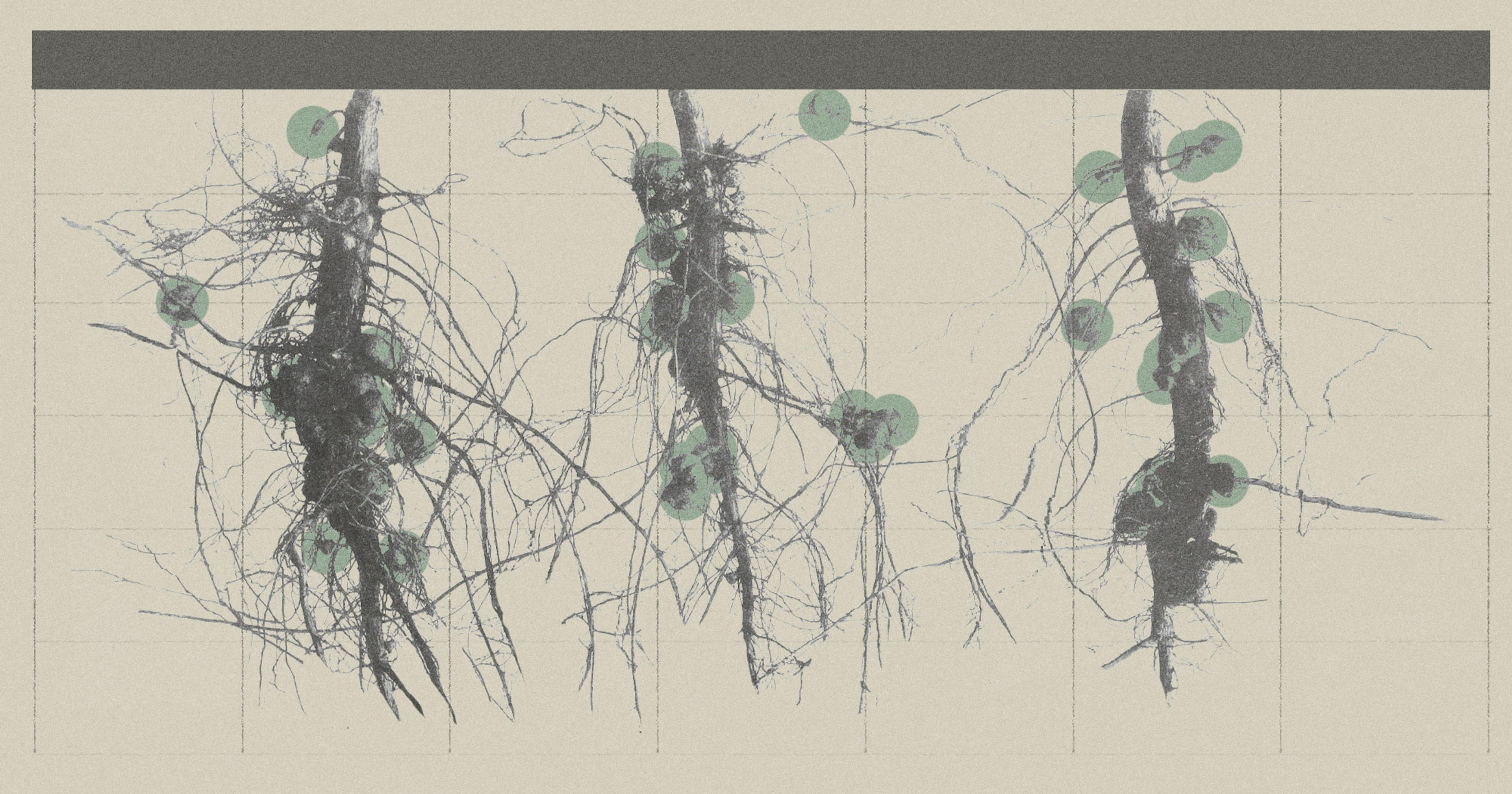

In fact, the World Bank estimates that up to half the seeds sold in many African nations are counterfeit, a figure that inspired researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to create a system for creating “unclonable” seeds. Using a popular technique for combating fraud in luxury goods and medicine called “physically unclonable functions,” or PUFs, a team of MIT scientists have created a kind of tiny biodegradable tag that can be applied relatively easily and cheaply to seeds themselves. And, perhaps most crucially, they can’t be easily copied.

The PUFs use the same logic as fingerprints — randomly generated patterns from nature that create a unique, irreplicable signature. “The idea is, it’s almost impossible, if not impossible, to replicate it, or it takes so much effort that it’s not worth it anymore,” said Hui Sun, a postdoctoral student in MIT’s Laboratory for Advanced Biopolymers.

“We were anticipating thoroughbreds, and we got sold a donkey.“

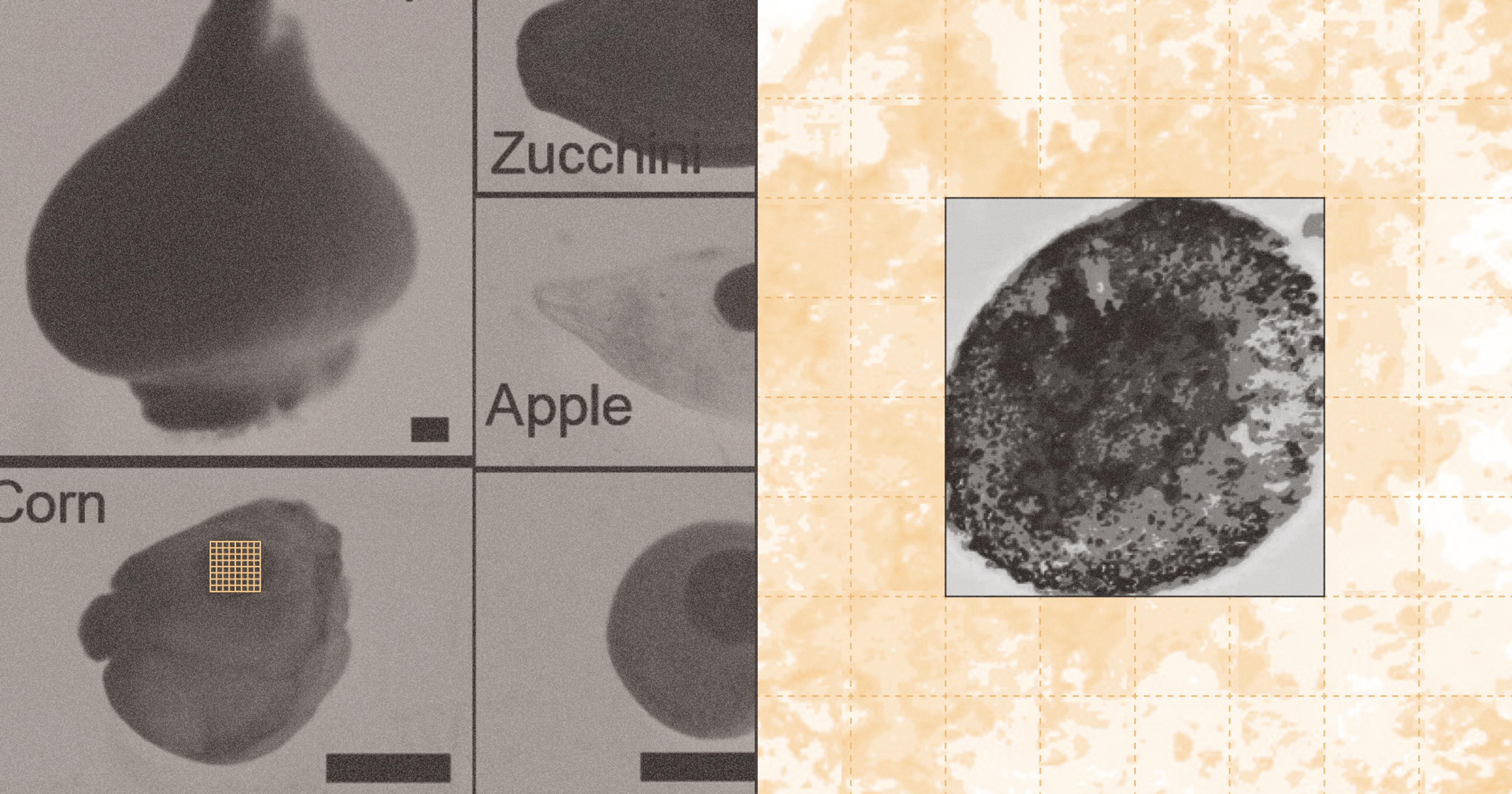

Sun and her colleagues created a system whereby miniscule dots of a silk-based material can be applied to seeds, with a unique chemical signature that would be extremely challenging to clone. Anyone with a cell phone camera macro lens could then access that signature in the cloud, to find which company the seeds came from, how old they are, and, crucially, a verification of quality level.

Mariam Gharib, a doctoral student in agricultural economics at Kansas State University, said that verification is sorely lacking in many parts of the world. Gharib studied the prevalence of seed fraud in Kenya for her master’s thesis while at the University of Delaware. She spoke to more than 260 small-scale Kenyan maize farmers about their seed purchasing patterns, and found that many have been conditioned to spend less money on seeds thanks to counterfeits.

“It is very common for lower-quality seeds to be repackaged in what might seem like an official pack from a trusted seed company, then sold for higher prices,” Gharib said, similar to what the Memphis farmers alleged. “But when those seeds end up giving a low yield, or not growing at all, farmers are unwilling to spend higher amounts for ‘improved’ seeds.”

The World Bank estimates that counterfeit seeds in sub-Saharan Africa are responsible for rice yields that are less than one-third of their potential, and maize yields less than one-fifth. Beyond Africa, counterfeit seeds have confounded authorities in India, China, Ukraine, and beyond. The MIT researchers see the potential for their work having outsized impact on global food security.

“We think our technology can be used to build trust,” Sun said. “It’s pretty simple: These farmers should be able to know what they’re purchasing.”

The researchers don’t envision every seed sold would get its own silk tag. Rather, each bag would contain a handful of seeds with PUFs — what MIT doctoral student Saurav Maji calls “golden seeds.” Ideally, seed purchasers could scan those golden seeds as verification that the product is what it claims to be. And not having to mark every seed keeps manufacturer cost lower, so farmers buying verified seeds wouldn’t be priced out. With no microscope or special equipment required to verify them, almost any farmer should be able to take advantage of the golden seeds.

“It’s pretty simple: These farmers should be able to know what they’re purchasing.”

Here in the U.S., where most seeds are purchased from official retailers, the potential for Maji’s accessible solutions may appear less clear. After all, Christopher Deegan, Wisconsin plant health director for USDA’s Animal and Plant Health and Inspection Service (APHIS), said that seeds sold on the retail market typically go through multiple levels of verification before being sold. For instance, Deegan’s team visits retailers to ensure that seeds are being properly labeled with expiration dates, germination info, species viability, and all other required technical info.

But what about those fake Stine seeds? They certainly weren’t the first or only domestic opportunity for seed malfeasance. For instance, heading into the pandemic, right before a nation of housebound hobbyists started gardening for the first time, a curious phenomenon emerged. Online shoppers started getting offers for exotic fruit and vegetable seeds: blue strawberries and rainbow roses and ginseng (a root) that grows from a tree. The only issue? None of these seeds were real.

The fake seeds were part of a convoluted global supply chain, routed through marketplaces like Amazon, sold to consumers directly without regulatory oversight. Deegan noted that even for commodity seeds that come through more typical supply routes, customs inspectors may not have the tools to ensure products are authentic.

“The inspector will look at it and say, ‘Okay, it says corn seed. I’m looking at the seed. Yep, that’s corn.’ And it has all the germination and technical information on the label. That’s pretty much where the customs inspection will end,” Deegan said. “They’re not going to do a genetic test on the seed to see if it has the GMO qualities or branding that it claims.”

Moving forward, Maji said there is still significant work to be done, in terms of figuring out the best way to scale up and distribute their anti-counterfeiting system. For her part, Gharib welcomes any improvements to the verification process, but cautions that it could be an uphill battle to regain farmer trust.

“At this point many farmers do not believe claims about seeds they might buy, so if you’re going to introduce a new system, it will need to be combined with dispatches of information to the target audience,” she said. “They’ll need to be retrained on what they assume … even to know these [verified] seeds exist will require very clear communications.”