New research reveals that notoriously efficient corn and soy harvests aren’t quite so efficient, after all.

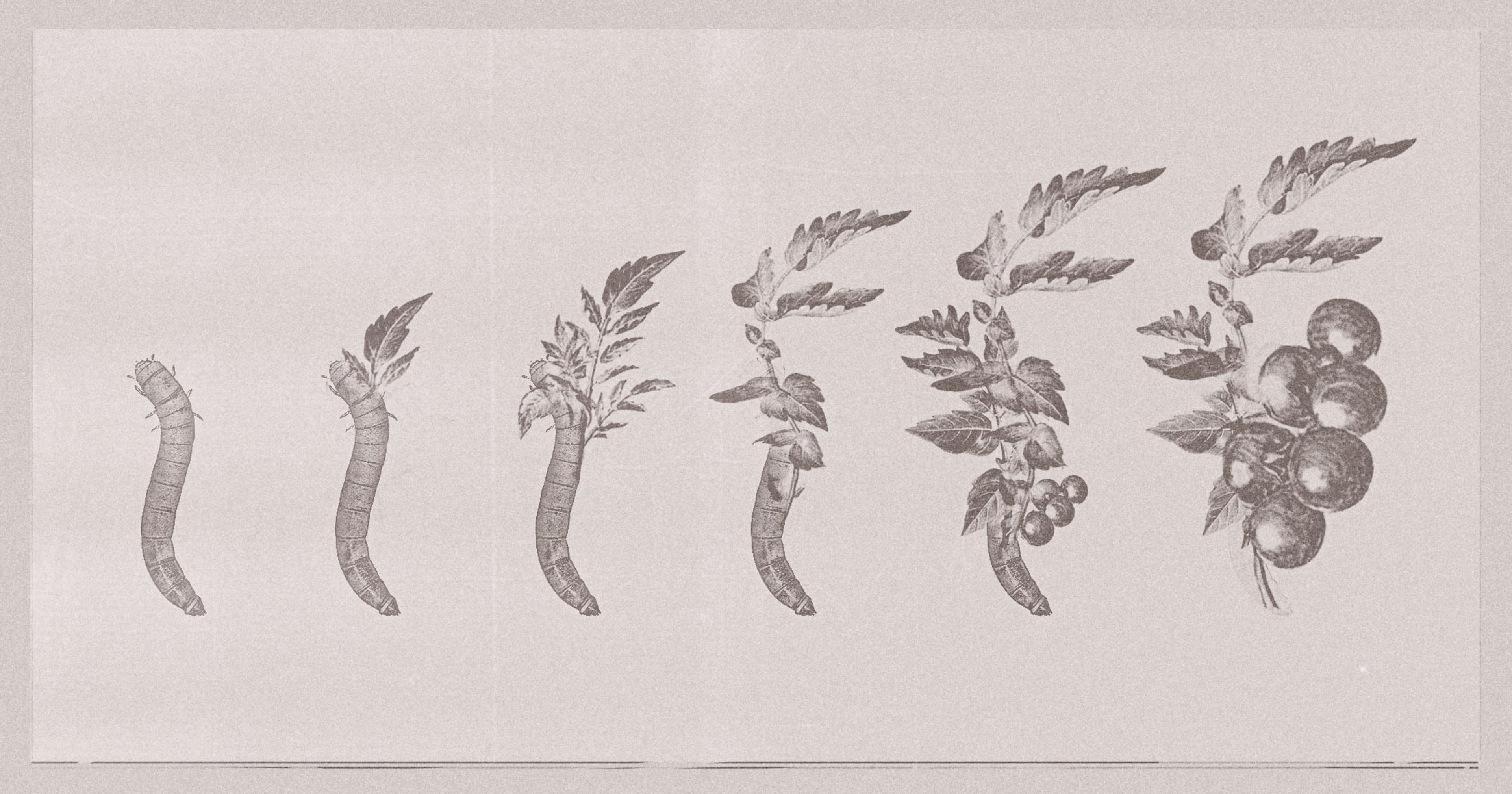

When it comes to fruits and vegetables, a staggering level of waste on the growing field is practically a given. For instance, a snapshot report of the 2017-2018 growing season found that a full 41% of fresh tomatoes in Florida, 40% of fresh peaches in New Jersey, and 56% of romaine lettuce in Arizona were left on the field.

But U.S. commodity crops like corn and soy have long been hailed as models of efficiency, with near-zero levels of harvest waste. “Between the technology on these combines and the level of detail that’s gone into modifying these crops so there’s low levels of damage, we have pretty minimal loss at harvest,” said Carlos Campabadal, an instructor in the grain science and industry program at Kansas State University.

However, recent research has revealed the loss to be significantly higher than expected: $2.6 billion worth of corn and soy each year, according to a new report from the World Wildlife Federation (WWF). Noting that most commodity grain research focuses on increasing yield, WWF’s researchers instead turned their sights on grain loss.

“When we looked at specialty crops [like edible produce] a couple years ago, we found that there were much higher levels of waste than growers predicted — just gigantic amounts, upwards of 40 or 50%,” said Leigh Prezkop, senior program specialist for food loss and waste at WWF. “We thought it was worth doing that same kind of investigation with other crop systems like corn and soy.”

The team’s methodology included reviews of available public data, interviews with farmers and extension specialists, and time spent observing a representative sampling of Midwestern farms. But why study commodity grains — and why now? The answer lies in the vast scope of corn and soy harvested in the United States — in 2021 alone, that was 15.1 billion tons of corn and 4.4 billion tons of soy. This staggering amount of product requires a lot of land, too: 92 million acres of corn and 83.8 million acres of soy planted in 2020. That’s a full 22% of American farmland; farming these crops is one of the biggest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions every year (a major factor in why these crops are so interesting to WWF).

Given the amount of land used and its level of impact, even a small percentage of wasted grain can bear outsized consequences. For corn, the expectations were for a 0.65% level of loss — extension agents encourage farms to aim for no higher than 1%. And for soy, the projected industry loss is around 3% each year. WWF’s researchers found significantly higher loss percentages: 4.7% of corn and 4.5% of soy are being left on the field. So this report has been met with some surprise.

“The most common reaction was like, ‘Oh gosh, I didn’t realize that it really added up to that,’” Prezkop said, referring to the farmers involved in the research when they were shown the study results.

Specialty crop waste stems from a wide host of causes, everything from labor shortages to lack of sufficient market demand to overripeness — fruits and veggies are famously perishable. But just two main factors accounted for the vast majority of corn and soy loss, according to WWF: older, inefficient harvesting equipment, and equipment operators with insufficient experience.

For farmers who are using older or less efficient combines, the idea of a costly equipment upgrade to a flagship model can be daunting. To mitigate this, WWF encourages more equipment sharing among farmers, an increasingly prevalent practice on the ground. “The larger farmers have the most advanced flagship models of combine harvesters and they have less loss where medium scale producers are less likely to have those advanced combine harvesters,” said Prezkop. “We’d certainly like to see more exploration of equipment-sharing programs.” Additionally, WWF is encouraging better training for combine operators on all sizes of farm.

It should be noted that annual grain loss may be much higher than this study shows. WWF’s specific focus on post-harvest loss doesn’t account for corn and soy lost during the growing season, or loss during storage and processing. Moving forward, Prezkop would like to see more research on pre-harvest grain loss. Also on the research wishlist: grain loss during storage and after.

“Just during storage, you can see insect infestation, you can see mold, you can see all kinds of things that can lead to damage and loss,” said Campabadal. “There’s a good amount of waste all the way from the drying stage to the end user.”