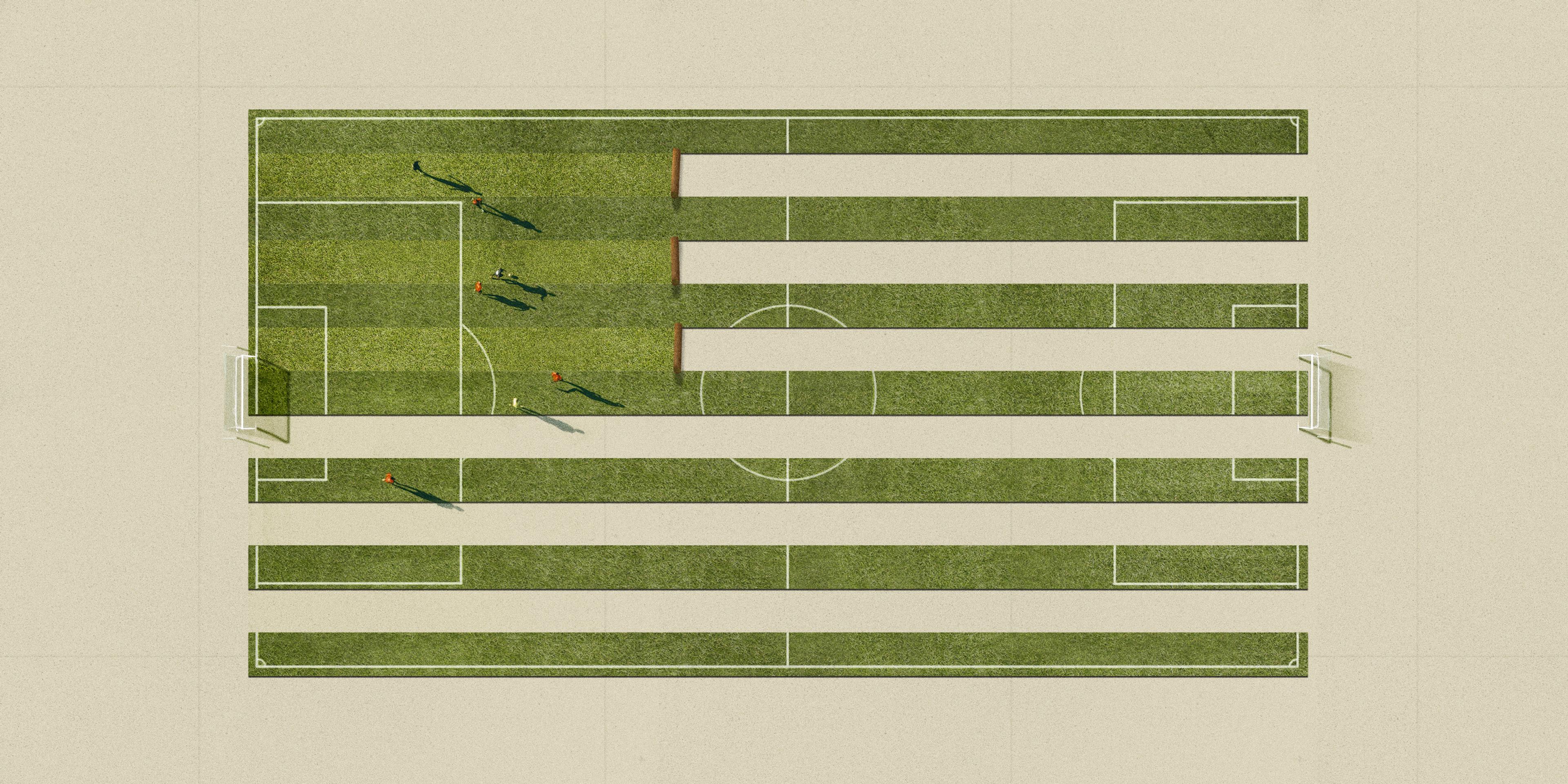

FIFA has spent many years and millions of dollars on turf research, ensuring this summer’s games will be played on truly exceptional fields.

In the summer of 2026, FIFA will stage its largest-ever World Cup on North American soil. Forty-eight national soccer teams will play in 16 stadiums stretched across the U.S., Mexico, and Canada — that’s more teams, more venues, and more host countries than ever before. And when the games kick off, they will put a five-year experiment — one of the biggest in turf science history — to the test.

Since 2019, FIFA has invested more than $5 million in a partnership with turf scientists at Michigan State University and the University of Tennessee, tasking them to solve a foundational challenge of the tournament: the fields.

Eleven of the 16 World Cup venues are primarily NFL stadiums, chosen for their huge capacities that more than triple the size of some North American soccer venues. Rather than pristine soccer pitches, these arenas function as multipurpose concrete shells hosting a variety of events. Many still deploy Astroturf instead of natural grass — which isn’t up to FIFA standards. Some will have as little as five weeks in their event schedule to bring in locally grown sod and establish a professional-grade soccer pitch before the tournament starts.

Researchers were charged with designing temporary natural grass fields that could rival Europe’s permanent pitches. The turf must meet FIFA’s exacting standards for ball roll, shock absorption, consistency, player safety, and broadcast appearance. All this while remaining as uniform as possible across all 16 sites, indoors and outdoors, from desert heat to northern cold.

Only the tournament will tell, but early trial games suggest the partnership was a big success. The turf science teams curated resilient grass combinations, grow-light recipes to keep the grass healthy over the 45-day tournament, and a way to build a game-ready grass pitch in under 24 hours. Their approach has the potential to become an industry standard, with applications for golf and American football, too. If it takes off, the U.S. sod industry will have some growing to do.

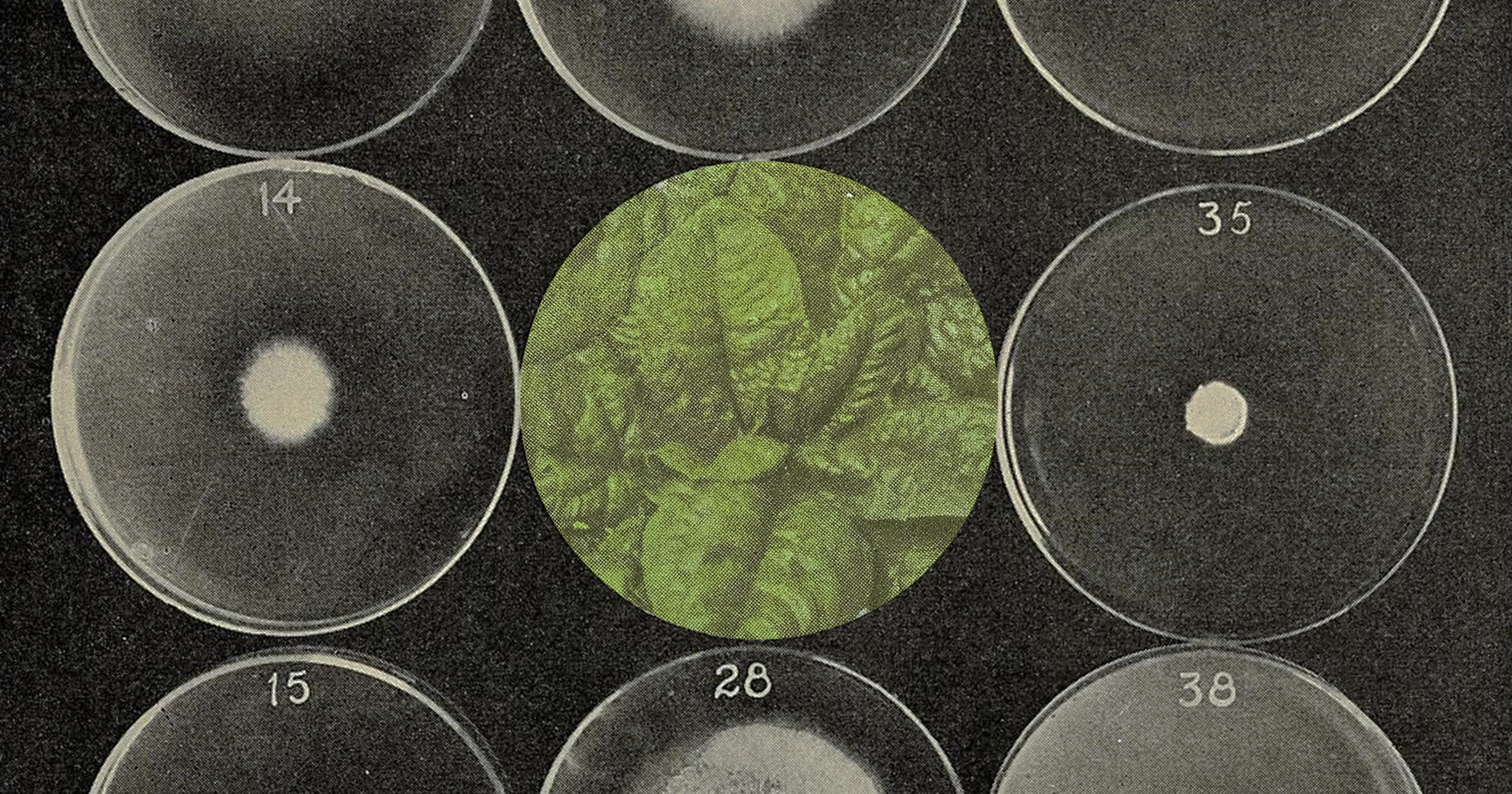

FIFA’s investment was a windfall for an industry that typically sees far fewer funding opportunities than other branches of agriculture. (See last year’s push to get sod farmers their own industry checkoff.) “The technology has always been there,” said Trey Rogers, turf scientist at Michigan State University. But for the first time, there was funding to see what their best approaches could do. “We were thrilled to get to put our theories to the test.”

A Boon for Sod Farmers

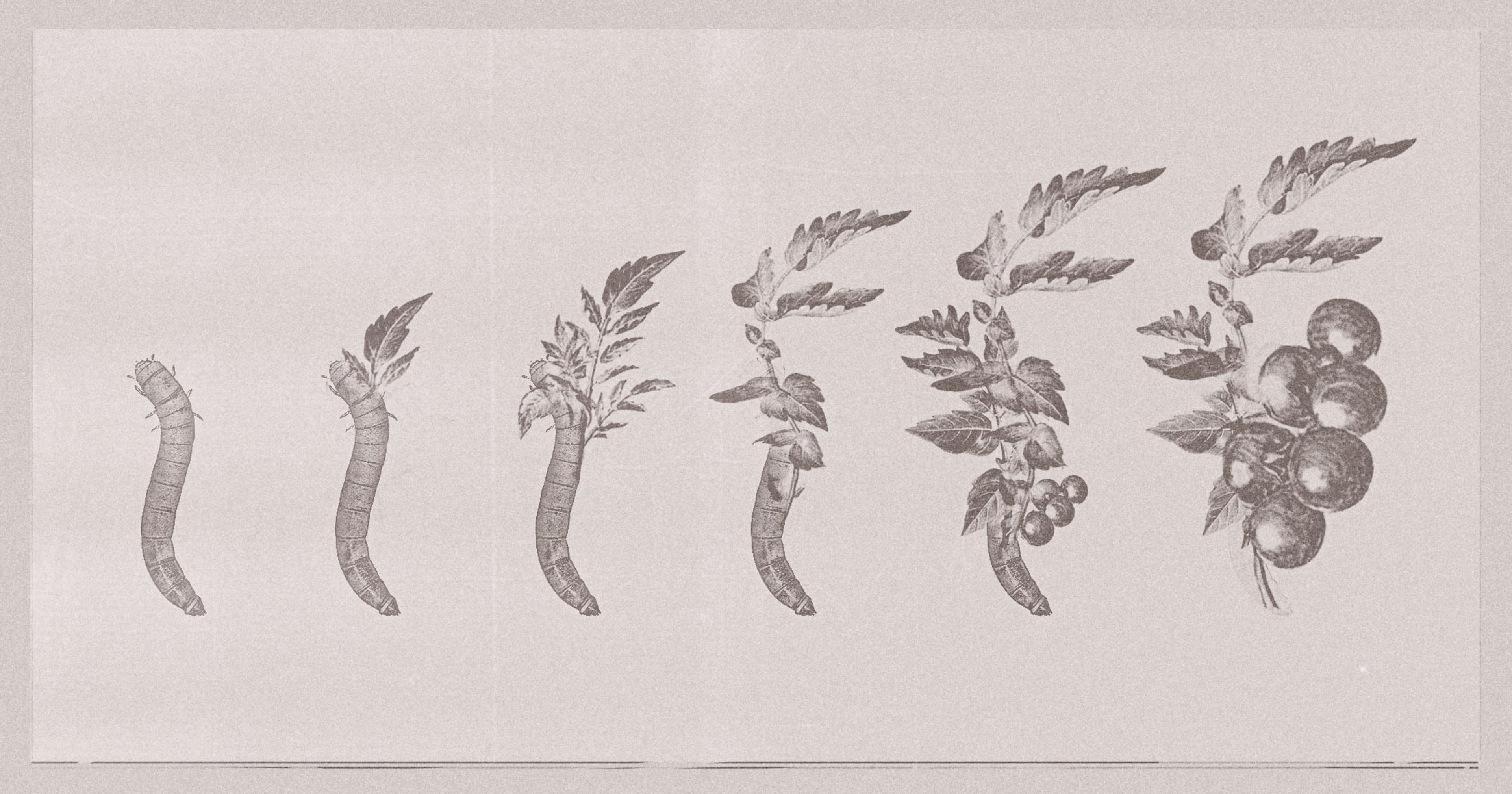

The researchers quickly convinced FIFA to procure their grass from sod farmers using a 30-year-old growing strategy called sod-on-plastic: Sod grown on a gargantuan sheet of plastic and only an inch and a half of sand. Where most sod is cut at the root with an underground blade at harvest, the super-compact root system of sod-on-plastic is easily peeled off its bed and rolled to be shipped across the country.

Because the roots are never damaged, sod-on-plastic faces less transplant shock and drought stress when it’s installed. Instead of waiting for the sod to adapt, this turf is playable almost immediately.

It’s generally the same strategy used for the 1994 World Cup, but John Sorochan, the turf scientist at the University of Tennessee who brokered the relationship with FIFA, said it’s not the same product he did his master’s degree on in 1995.

The management on-farm has intensified with factors like daily mowing prescriptions and hybrid turfs that use synthetic material to support the natural grass. “It’s like game day-ready stuff,” Sorochan said. And once the grass is laid down in the stadium, Sorochan’s team developed highly specific grow-light recipes that help the grass recover from player wear and tear. It’s up to playing standards, but also FIFA’s aesthetic standards for TV viewing.

Local sod-on-plastic growers across the continent have been contracted to deliver new sod-on-plastic sheets of Bermuda and bluegrass to 15 of the 16 stadiums before June. They’ll layer the rolls over eight to 12 inches of sand for smoother passes, just the right amount of ball bounce, and minimal impact on players‘ bodies. Three of the pitches are already installed.

FIFA’s investment was a windfall for an industry that typically sees far fewer funding opportunities than other branches of agriculture.

The sod-on-plastic approach has remained very American over the last three decades. But FIFA’s involvement has piqued international interest. The technique has spread to Canada, Mexico, and Brazil — host of the upcoming Women’s World Cup — with Spain and Portugal also showing interest.

There’s been growth in the U.S. too, Rogers said. While still niche (there are fewer than 20 sod-on-plastic growers in the U.S.), Rogers said the number of these farms has tripled just since 2021.

And there could be room for more growers to get involved. With FIFA’s partnership, Sorochan and Rogers developed sod-on-plastic solutions that could have applications beyond soccer. The biggest development involves a plastic piece called a Permavoid. Used to create drainage in turf projects, Permavoid looks similar to the plastic pieces used to ship bottled soda. Sorochan and Rogers took an off-label approach and used it as a sort of subfloor to the soccer field, under just two inches of sand and the sod.

It worked better than expected. The ball bounce, the force on the player’s bodies — “It’s the same as if it were on 12 inches of sand,” Sorochan said, all while being 70% to 80% lighter. “When a player hits that surface … that Permavoid dissipates the energy of the player hitting the surface. They don’t pick up the hardness of the concrete below.”

In summer 2025, the new combo was tested at AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas, for the Concacaf Gold Cup. It played as well as a classic grass field, Sorochan said. But it can be installed in just 17 hours with a 20-person team and removed in just seven hours.

Now Do American Football

FIFA’s multi-week tournament won’t need this kind of versatility, but it’s a game-changer for American sports, Rogers said. Most of the time, stadiums are rotating between multiple events each week. With the permavoid, “you could put a [grass] field in on a Tuesday, play a game on Saturday, take it out and have a concert on a Sunday,” Rogers said. “It’s a way to get rid of Astroturf, a way to have grass indoors.”

That could be a welcome opportunity for the NFL, which currently gets tons of pushback from players who want the same privilege as their soccer colleagues: grass-only fields. Data repeatedly show that non-contact player injuries are higher on synthetic fields. While switching won’t be cheap, sod-on-plastic plus Permavoid is definitely within the turf budget most NFL teams allot, said Chad Price, sod farmer and owner of a turf installation business that works with a variety of NFL, MLB, and professional soccer teams. “Compared to what they invest in everything else, it’s certainly affordable to them.”

The same combination holds promise for golf, too, Sorochan said. It’s a way to repair damaged tee boxes so that they’re immediately playable. And courses can also apply the same grow-light recipes to help tee boxes recover from damage, he said.

“You could put a [grass] field in on a Tuesday, play a game on Saturday, take it out and have a concert on a Sunday.”

Athletic fields and golf courses already make up 24% of sod sales. And researchers agree that, while sod-on-plastic is niche, there’s room for more venues to use it and for more existing sod farmers to upgrade to the premium crop. Plus, tapping into the athletic market offers a way for farmers to hedge against the fluctuating housing market.

Detractors argue that expanding sod production is a misuse of agricultural land, depleting high-quality soil that should be used for essentials like food. In this debate, Rogers said, sod-on-plastic may prove less controversial than traditional sod farming. Because the sod is grown on plastic, it doesn’t need to be grown in prime soil or to extract the top soil layer at harvest. The athletic turf can be grown on marginal land that farmers don’t otherwise use, even concrete, he said. “I’ve always said this could be done in the parking lot of an abandoned mall.”

As for the research partnership with FIFA, this summer marks its end. But there are murmurings that the soccer organization will continue to consult with UT and MSU for World Cups to come. Even if not, Sorochan says the funding has transformed, not just athletic fields, but turf agriculture. “I think the big thing is the legacy, FIFA’s good impact, I think it’s beyond soccer.”