As pollinator populations continue to struggle, researchers are modifying drones to help almonds, apples, and other tree crops.

Half of North American bee species are in decline and a quarter at risk of extinction, as bee populations face daunting challenges like habitat loss, pesticides, and disease. This is a problem for ecosystem health, but it’s particularly acute for many of our edible crops.

In the United States, honeybees, which do the bulk of agricultural pollination, are shipped to California in February for almond season, then to Washington two months later when the apples bloom as the beekeepers try to match the demand. When sunflower and canola season falls later in the summer, the bees need to be moved back.

“There’s a supply and demand issue,” said James Strange, professor of entomology at Ohio State University. “Demand for food has grown, [which] means that we need hives of bees moved to places where plants are blooming at that moment.”

Or we can turn to robots.

In the U.S., the dinner plate-sized Dropcopter drone can now be seen releasing dry pollen from what looks like a WW2 aircraft ball turret under its belly. One person can manually pollinate five to 10 trees a day, while Dropcopter will cover 40 acres in around four hours. Since the robot bee was first used in 2017 to pollinate almond orchards in New York, it has been used to pollinate almond, apple, cherry, and pistachio orchards from California to Brazil.

In 2017, Dropcopter co-founder Matt Koball and Adam Fine visited a food conference in San Francisco. Fine was about to launch a drone food delivery company, but when they were at the conference, they heard an almond grower complaining about the increase in beehive rental costs during the pollination season. At that time the rental fee had risen from $150 to $175 per hive. Now in 2025, it can cost up to $225 a hive during peak pollen season.

Koball was an olive farmer, so he was aware how the almond growers used bees to pollinate their trees. “They put trays of pollen in front of the beehives. The bees [collect] a load of pollen on their way out to the field,” said Koball. “I started thinking about doing this with a drone and we went from delivering food to delivering pollen.”

The duo spent the next four months in a garage creating a rudimentary robot bee using an upturned salsa pot filled with pollen that would sit underneath a drone. The robot would fly high above the orchard and scatter frozen pollen over the trees. They trialed the robot bee in an almond orchard as it is the first to blossom in the United States; it’s also one of the hardest trees to pollinate.

After joining an incubator program, Koball and Fine ended up building a patented device that was able to meter out pollen at a specific rate and a steady speed. The Dropcopter team expanded to working with cherries and apples, which proved to be even more successful than almonds. Koball says the almond orchards saw a 25% yield increase while cherry orchards saw a 45% increase. They now rent out Dropcopters for up to $375 an acre.

The almond orchards saw a 25% yield increase while cherry orchards saw a 45% increase.

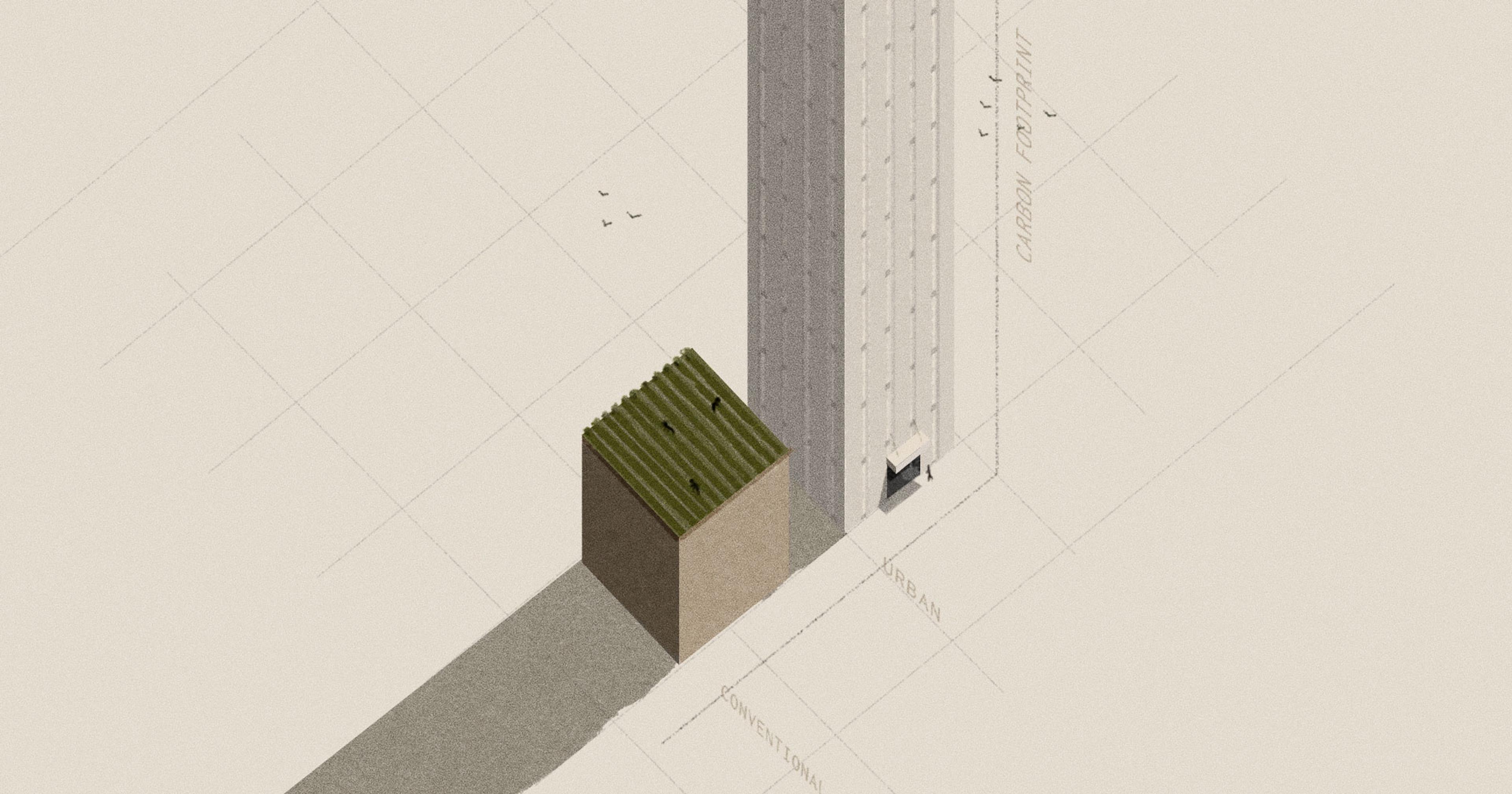

Of course, Dropcopter is not the only company working on robot bee technology. Singapore-based company Polybee is using robot bees to pollinate fruit farms in Australia and Europe. When its founder Siddharth Jadhav was studying drone tech in 2019 at the National University of Singapore, food security and vertical farms were a large part of the national conversation.

Singapore, which launched the world’s first vertical farm in 2012, imports 97% of its food. Jadhav decided to see how his drones could help vertical farms. When the autonomous Polybee hovers above self-pollinating plants such as tomatoes and strawberries, the downforce from the drone causes the plants to shake and the flowers release their pollen.

Robot bees were of particular interest to the indoor farmers in Australia as the country doesn’t have native bumblebees, so they need to pollinate indoor plants by hand. This can mean tapping the plant, brushing by hand, or even using leaf blowers.

Polybee’s software pilots the drone and uses the robot bee’s camera to recognise flowers and fruit. It also enables multiple robot bees to fly at one time without bumping into one another. Just two robot bees can pollinate a hectare of plants in a greenhouse within a few hours.

The robot bee can not only pollinate the plant, but help the farmer forecast yield and detect disease or nutritional deficiency. “What we’re doing at Polybee is [turning] unpredictable farms into data-driven factories,” said Jadhav.

Mark Fielden, CEO of Borotto Farms in Victoria, Australia, has been using Polybee’s robot bees not for pollination, but to analyze yields within its 400-acre farm. At one time the team would have walked the paddocks themselves, assessed the crop, and had their own opinions on whether it was the right time to harvest. “At $3 a kilo [for a spinach crop] you can be looking at $1,200 an acre a day if you get it wrong,” said Fielden. “[Polybee] flies itself every day over fields and paddocks. It measures all the leaves and gives you an objective view.”

Just two robot bees can pollinate a hectare of plants in a greenhouse in a few hours.

A swarm of other robot bees are also being created in labs, and they seem to be as varied as the ones in nature. In the Netherlands, startup Flapper Drones has designed a robot bee that can be used for pollination, with wings made from lightweight space blankets. This helps keep people safe as they work in proximity to the robots.

In 2017, researchers at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology created a robot bee using a 4 cm-long toy drone covered in horsehair bristles and a sticky gel. While the pollen was transferred between the lily plants, it was reported the drone’s wings damaged the petals. In 2020, the team trialed another form of pollen dispersal by fitting the robot bee with a delivery system that would fire pollen-filled soap bubbles onto flowers.

A different project in the United States seems to have solved the problem of having the robot bees damage high-value crops. Associate professor Kevin Chen, head of the Soft and Micro Robotics Lab at MIT, has designed a bee that will land as softly as a water boatman upon a petal. Building on the work of the RoboBee team in the Wyss Institute at Harvard, Chen has designed artificial muscles that contract when voltage is applied.

Chen’s robot bee, which is tethered to a power source, is currently limited to flying between plastic flowers in the lab, but the robot engineer can see its potential. “Bees are doing great in terms of open-field farming,” said Chen, a statement some would surely disagree with. “But there is one potential type of pollination I think we can consider in the longer team, which is indoor farming.”

Entomologist professor Strange said: “The nice thing about putting a hive of [actual] bees into a greenhouse is they find the flowers themselves. You don’t have to worry about them getting caught up in the ropes or hitting the lights. [But] as drone technology gets better that might be an area where I actually would say, ‘Okay, that makes sense.’”

We’re not anywhere near a point in bee decline [where] some of our crop plants are going to go extinct. But we’re definitely at a point where we are looking at increases in costs for beekeepers, orchards, [and] farmers. Those are going to go up, so we’re going to pay more.”