Common knowledge said there was only one way to grow hydroponically. Until a simpler method turned viable — and viral.

When Bernard Kratky left his Hawaiian home and horticulture research in the ‘80s, he went to learn from another island across the planet with similar challenges. Taiwan, and its Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, was running ambitious experiments to grow resilient crops in developing countries.

Breeding sweet potatoes and mung beans, developing disease-resistant tomatoes, and reducing fertilizer inputs were some of their priorities. Among all of the vegetable excitement, Kratky saw researchers growing crops without soil, hydroponically. He had grown some crops this way before, but in Taiwan he saw something new: hydroponics using no electricity or aeration whatsoever. This ran contrary to every growing system of the time, so he dismissed it and focussed on other research. But its memory stuck with him when he returned to Hawai’i. Now, almost 40 years later, people worldwide know the style of growing hydroponics without any aeration as the Kratky method.

Back at his home and work at the Volcano Agricultural Experiment Station in Hawai’i, Kratky encountered the same farm struggles that the islands have always had to deal with: weeds, nematodes, and extremely depleted soils. On top of that, certain areas didn’t have access to power, and he needed to grow successfully while leaving for extended periods. Frustrated with these pervasive challenges and informed by his observations in Taiwan, he and a farm foreman removed a door from an old refrigerator and laid the fridge on its back. He filled it with water nearly to the top, added a makeshift cover, and suspended young tomato plants above the nutrient solution, dangling their dainty roots into the water below. Unlike other hydroponics at the time, this system had no pumps and no power.

Kratky left for a trip and didn’t think much of the experiment. When he returned, he was surprised to find the tomatoes flourishing with their roots reaching deep into the baby blue fridge’s now-depleted reservoir, surviving without additional inputs or supervision.

Kratky began publishing his findings on non-circulating systems in 1990, but it didn’t gain much popularity until the internet got ahold of it in the mid-2000s. Today it is proliferating among growers around the world where infrastructure and inputs are more limited. What began as a practical response to Hawai‘i’s production barriers is gaining traction in places where simplicity is not a weakness but a necessity.

How It Works

The principle is disarmingly simple. Plant roots require oxygen to function, so when hydroponic growers fully submerge the roots in water, they also submerge a weighted bubbler connected to an air pump. By contrast, in the Kratky method, the container is filled once with nutrient solution and water. As the suspended plant sucks the water, the exposed upper roots switch from processing the nutrient solution to processing the air between the water and the container’s cover.

Kratky summarizes the streamlined system as a tank, a cover, and net pots. The nutrient solution is put in place “at the time of planting or transplanting” and then left alone. There is no electricity, no circulation, and no moving parts.

“Typical hydroponic growers are on call 24 hours per day and always checking on the operation,” he wrote. “However, Kratky hydroponic growers normally just fill the tanks with nutrient solution, plant or transplant the crop, and do nothing until harvest.” Growers can leave for five weeks and return to find lettuce ready for harvest.

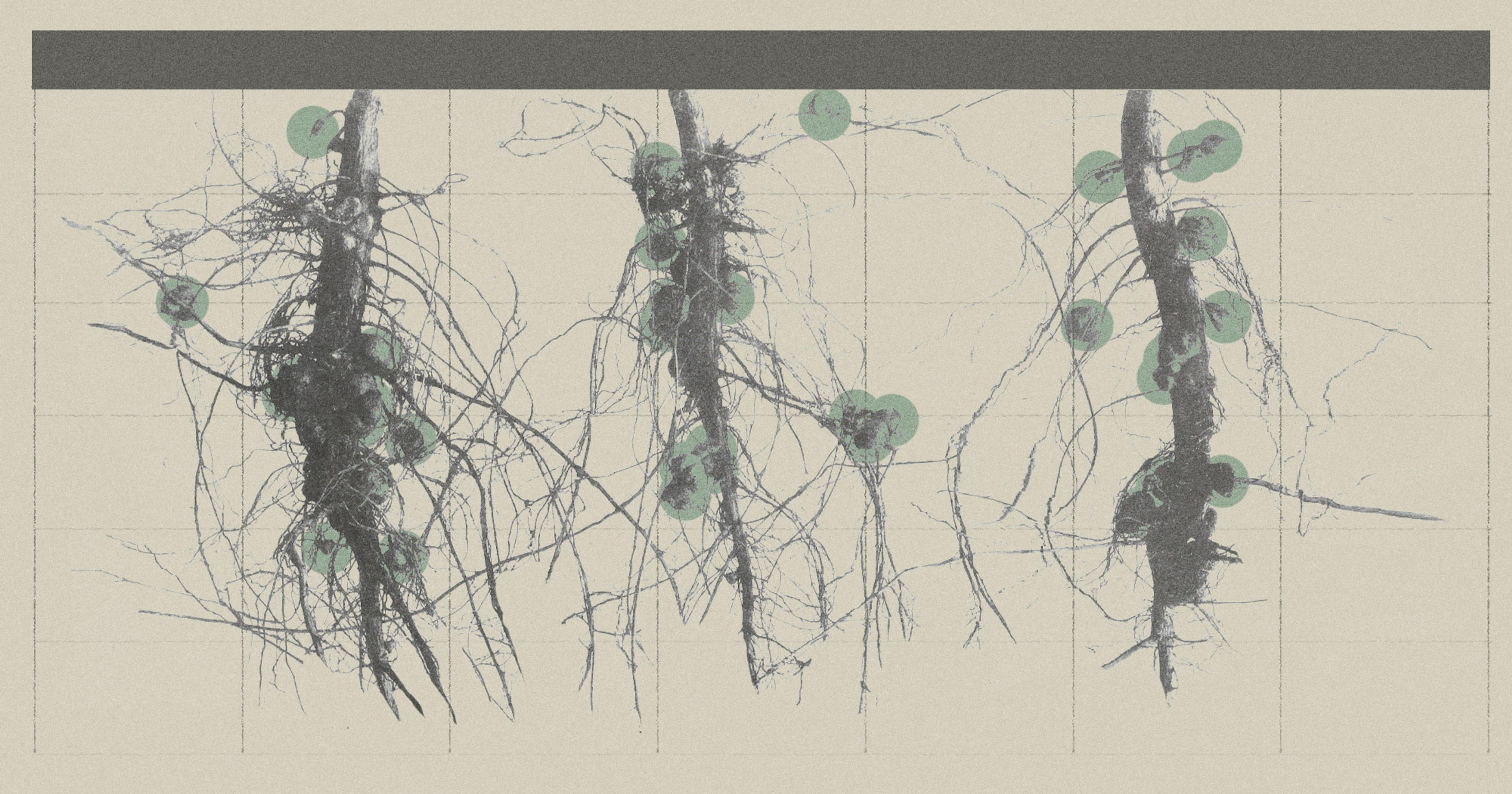

A recent study from Uganda found that the vertical Kratky system produced lettuce yields similar to those grown in soil-filled grow bags and allowed producers to grow in multiple vertically stacked racks. The authors argued that the system could support urban food production and income generation in developing countries, especially given the lack of electricity requirements.

Why the Industry Dismissed It

While the history of hydroponics dates back to ancient systems in Babylon and the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, modern hydroponics is generally considered to have emerged in the 1930s from UC Berkeley professor William F. Gericke and his nutrient solutions. Then in the 1970s, plastics became more commercially available, and they allowed commercial growers to scale up for the first time. The containers, gutters, tubes, and other parts that used to require glass, ceramics, and stainless steel could now be fabricated quickly and cheaply for hydroponic farms.

Both universities and large farms had something in common. They both had access to plenty of infrastructure and electricity. So when these resource-rich growers then wrote books and taught the world how to grow food without soil, they declared that pumps and aeration were essential for plant growth.

As a result, Kratky said his early work did not receive much attention from professional hydroponic circles; his first manuscripts were rejected from publication. Then at a 2005 hydroponics conference in New Zealand, two scientists publicly objected to his findings and insisted that Kratky systems could not have similar yields to those with supplemental oxygen. The skepticism was based not on specific data but on assumptions already entrenched in the field.

Nathaniel Heiden, plant pathologist and research director at Levo International, a nonprofit farm based in Connecticut, said that when he first encountered Kratky’s papers in 2016, the method still generated little discussion. “I sometimes talk now with hydroponic growers and experts who write off the Kratky method and assume that you need an air stone [an oxygenating air pump] to get optimal yields,” he said. The belief that dissolved oxygen must be mechanically supplied was widespread enough that Heiden and collaborators at Cornell, Ohio State University, and the University of Connecticut designed trials to compare systems directly.

“We were shocked to find repeatedly that Kratky systems with and without air stones performed similarly and that Kratky systems even performed similarly to more intensively monitored deep water culture systems,” he said. Their core findings, one of the first scaled up experiments to directly compare yields between Kratky and conventional hydroponics, showed that hydroponics with no power can produce almost the same yield, as long as some of the roots are exposed to absorb oxygen.

“Most areas of farm fields and even most backyards don’t have available electrical power so Kratky hydroponics can easily be done in places that would require a lot of infrastructure investment.“

Joe Swartz, senior vice president at American Hydroponics, has been growing with commercial hydroponic systems for more than 40 years with large growers. When asked about the Kratky method’s possible applicability in large farms, he said, “Unfortunately, no, not in a commercial application. Aeration is only one of the challenges. Root systems produce waste products, such as ammonia, which in the soil or other hydroponic systems is either carried away by nutrient flow or broken down by beneficial microbes. In a Kratky system, the plant produces ‘air roots,’ but the nutrient solution can become quite stagnant, which inhibits these microbes. The microbes die, ammonia builds up and the plant can begin to literally poison itself.”

Kratky himself acknowledges these limitations. He estimates that circulated and aerated systems can achieve roughly one-third higher yields when perfectly managed.

Still, setup of Kratky’s system is quick and inexpensive, safety worries about electrical power are eliminated, and there is no concern over breakdown of equipment or loss of power. Yes, a tank leak could cause a failure, but that could also happen with an aerated or circulated system. And Kratky said little experience is needed as he has taught this system to elementary school students. Additionally, he said, “Most areas of farm fields and even most backyards don’t have available electrical power so Kratky hydroponics can easily be done in places that would require a lot of infrastructure investment for conventional hydroponics.

Typical hydroponic growers are on call 24/7 and usually perform some maintenance operations during the crop growing period. However, Kratky hydroponic growers normally just fill the tanks with nutrient solution, plant or transplant the crop and do nothing until harvest.”

Where the Method Has Taken Hold

The Kratky method has struggled for acceptance in large-scale operations in the United States, but its adoption elsewhere tells a different story.

Heiden and Levo International describe using Kratky systems in Hartford, Connecticut, at a scale sufficient to supply their CSA farm and market stand. The systems have also been central to their work in Haiti, where electricity is unavailable or unreliable in many communities. In those settings, Heiden said, the method was “the only hydroponic approach that can be successful with a set-it-and-forget-it approach.”

Levo’s lead Haitian researcher, Girlo Augustin, has used the systems to test nutrient sources and substrates that can be produced locally. Heiden noted that their team has grown crops ranging from peppers to spinach in these Kratky systems, known locally as Bokits.

The MethodsX study from Uganda points to a similar pattern. The authors frame their vertical Kratky system as a tool to address urban land scarcity and to provide fresh vegetables where soil cultivation is constrained. They describe the method as low-cost, low-tech, and potentially transformative for food access in developing countries.

The common thread is not yield maximization but accessibility. In Hawai‘i, non-circulating hydroponics offered an escape from nematodes and poor soils in remote areas. In Hartford, it provided an affordable entry point for community-based production. In Haiti and Uganda, it offered a way to grow food where electricity, inputs, or infrastructure were unavailable.

Growing Outside the Frame

Kratky didn’t name the method after himself. but it became popular after a MHP Gardener, a grower on YouTube, released a video entitled “Easy Hydroponics — Anybody Can Do This,” that became viral in hobbyist hydroponic circles. Other hobbyists began experimenting, posting videos, and reaching large audiences, using the term themselves.

“The name stuck,” Kratky said.

Today, the method is thriving in an interactive, scientific community on YouTube with hundreds of growers reviewing and adapting each others’ systems. As the Kratky method grew in popularity, the academic community has responded by quantifying and publishing results on the method — despite initially dismissing it.

The Kratky method is unlikely to shift large-scale commercial operations, but it has created a simpler option for growers in very different situations. It begs the question: What other technologies and techniques seem too simple to work? Frustrated scientists, stubborn hobbyists, and YouTube may hold the keys to adapting new agricultural technologies to widespread applications beyond what the universities and commercial industry consider viable today.