Tech-driven, soilless farm systems can serve as a useful tool to save water and shore up the supply chain. But the process comes with not-insignificant challenges.

Growing plants inside isn’t exactly a novel practice — greenhouses have provided farmers an indoor, climate-controllable option for centuries. But the future of food grown indoors may look a little different.

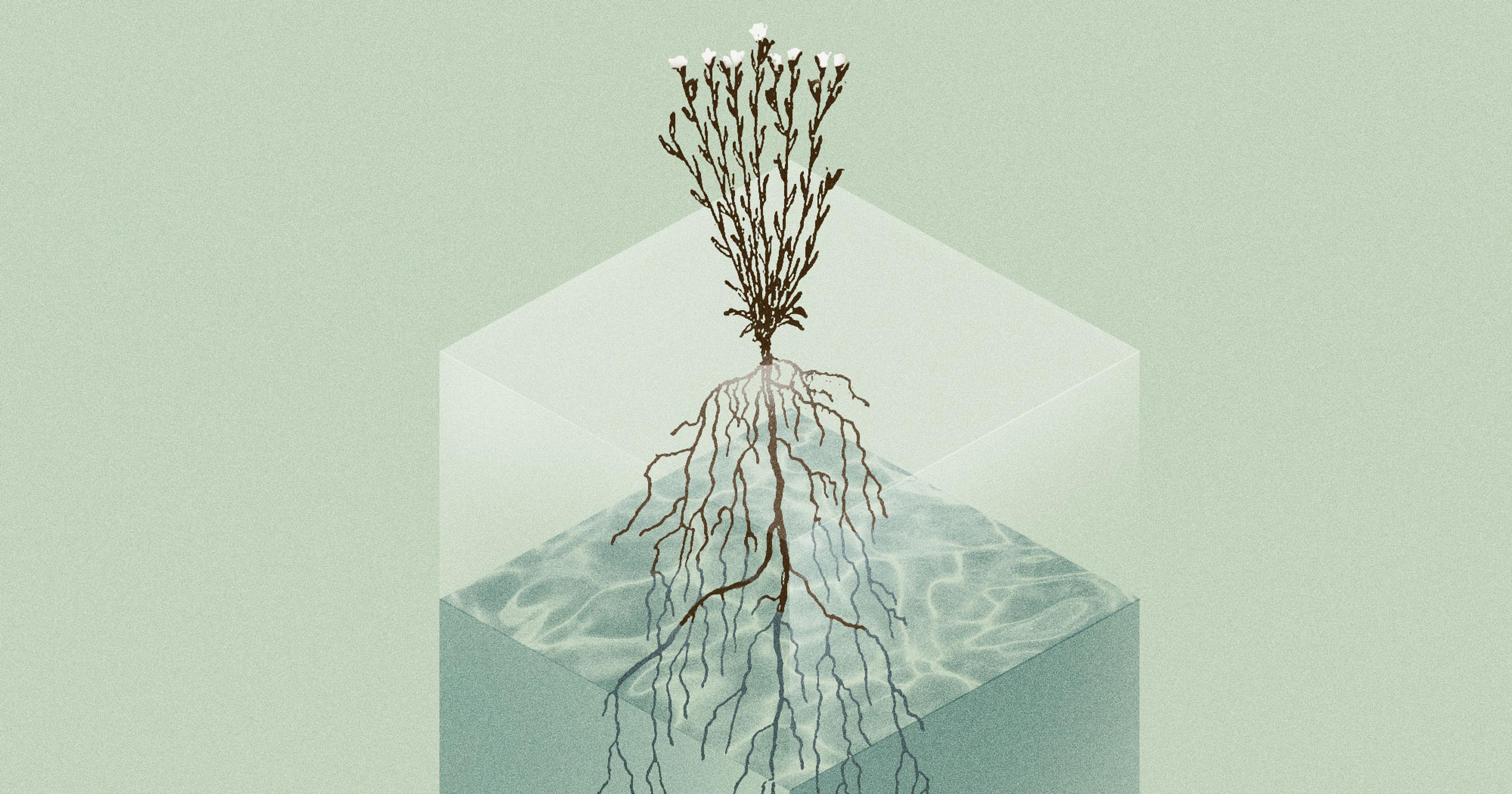

In recent years, we’ve witnessed the rapid rise of technology-driven indoor farming systems that allow crops to grow hydroponically — relying on a water-based nutrient solution rather than soil as a growing medium — and aeroponically — building a soil-free environment that relies on mists and air to supply plants with nutrients.

But the broader picture of soilless farming is not without its downsides, and its structural hurdles. To dig into the potential of these soilless indoor growing systems, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) spent the past couple years researching the practice, and what these systems could mean for the future of the food supply chain. The nonprofit recently released a comprehensive report, highlighting major pros and cons of this type of farming.

Instead of large swaths of outdoor land or access to sunlight, these growing systems typically exist in more urban spaces, often within converted warehouses and on rooftops. Rather than traditional crop rows in the ground, the produce here grows on rows and rows of shelf-like units, stacked from floor to ceiling — aptly named “vertical farming.” Instead of sunshine, technicians rig up precision lighting systems that provide the right rays to satiate the plants.

“Plants don’t need sunlight, they need a specific spectrum of light and we can deliver a lighting array that is very targeted with LEDs,” said Marc Oshima, co-founder and chief marketing officer of AeroFarms, a large-scale commercial indoor farming company with locations across the U.S and internationally. No soil, no sunlight, no problem.

Vertical farming systems, according to WWF’s report, require upwards of 95 percent less water use — a major talking point for their proponents. The controllable nature of the growing environment also allows indoor vertical farmers to eliminate the need for pesticides. And with full ability to control the climate, vertical farmers have no risk of losing yield thanks to extreme weather events.

Advocates also note that because of the urban setting of many of the farms, harvests often have less distance to travel to consumers, resulting in a lower carbon footprint and reduced food waste. The indoor operations also have the potential to decrease land-use pressure. According to Oshima, an AeroFarms operation can yield “up to 380 times greater productivity per square foot than the field farm on an annual basis.”

To date, most vertical farming operations focus on leafy greens — currently the most profitable crop to grow indoors. By focusing on greens, often high-end, higher-priced boutique options — think micro broccoli greens, baby romaine, micro arugula — the farms are able to swing a profit despite high operation costs and energy needs. This does, however, mean higher prices on grocery shelves — as WWF points out, this complicates the opportunity for vertical farm produce to address food security across income classes.

According to the report, the high energy footprint of indoor farms remains the biggest hurdle facing the industry. With reliance on LED and other artificial light rays to grow the plants, the operations require quite a bit of electricity. And all those lights also generate heat, so to keep the environment at a stable growing temperature requires even more energy.

The high energy footprint of indoor farms remains the biggest hurdle facing the growing industry.

These farms often commit to creating their own unique lighting and growing technology — meaning they are often just as much a tech company as a farm. This means high start-up costs that could be restrictive to a small-scale farmer who may want to dip their toe into profitable hydroponic or soilless growing.

“Right now most [vertical] farms are sort of investing in everything,” said Julia Kurnik, WWF’s director of innovation startups. “So they’re a farm but they’re also investing in developing their own growing system. It’s a huge learning curve for every farm because they’re both a tech company and a farm and it’s hard to be both.”

While there is no denying the operations require a lot of electricity, Aric Nissen, chief marketing officer at Kalera, another large-scale vertical farming operation, claimed that a look at the “bigger picture” of the farms’ overall carbon footprint offsets the energy need.

“95% of the leafy greens in the United States are grown in either Arizona or Southern California and are consumed elsewhere, which means they travel a lot of miles to get there,” he said. “You look at the carbon footprint of a lettuce grown in, let’s say California, and shipped to Orlando, Florida versus grown in Orlando, Florida. There’s a carbon benefit of being grown in Orlando, even with all of the electricity being used.”

Kurnik also highlighted that in addition to the benefits of less travel time for leafy produce, vertical growing systems scattered around the U.S. provide a buffer in case of crop recalls in prominent greens-growing regions. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2019-2021 nine multi-state foodborne illness outbreaks were linked to leafy greens.

“There have been recalls nearly every year for the last handful of years,” said Kurnik. “You might remember when there’s no Romaine to be had anywhere for a month. So being able to diversify that supply chain is a big value add.” (While supply chain diversification is a worthy goal, it should be noted that indoor farms are not immune to foodborne pathogen outbreaks.)

Another current limitation of soilless growing is crop type. Large-scale operations like Kalera and AeroFarms remain mostly leafy green-focused and have contracted deals for these products with grocery chains like Whole Foods and Kroger.

That said, researchers are working to broaden the scope of what indoor farms can grow. At AeroFarms, entire growing sites are dedicated to research and development, in labs that specialize in optimizing other crops like berries and tomatoes for indoor growth. The goal, said Oshima, is not to outgrow the traditional ways of in-the-dirt farming, but to streamline farming no matter what medium.

Still, Kurnik doubts there will ever be a time that large-scale commodity crops like wheat or soy will be practical to grow inside. “Things like rice and soy and wheat, you can grow them indoors, but you need so much of them and they’re very, very low-margin crops. I don’t know that you will ever see a time that those are profitable to grow inside, not at the mass scale we need them,” she said.

Kurnik doubts there will ever be a time that commodity crops like wheat or soy will be practical to grow inside.

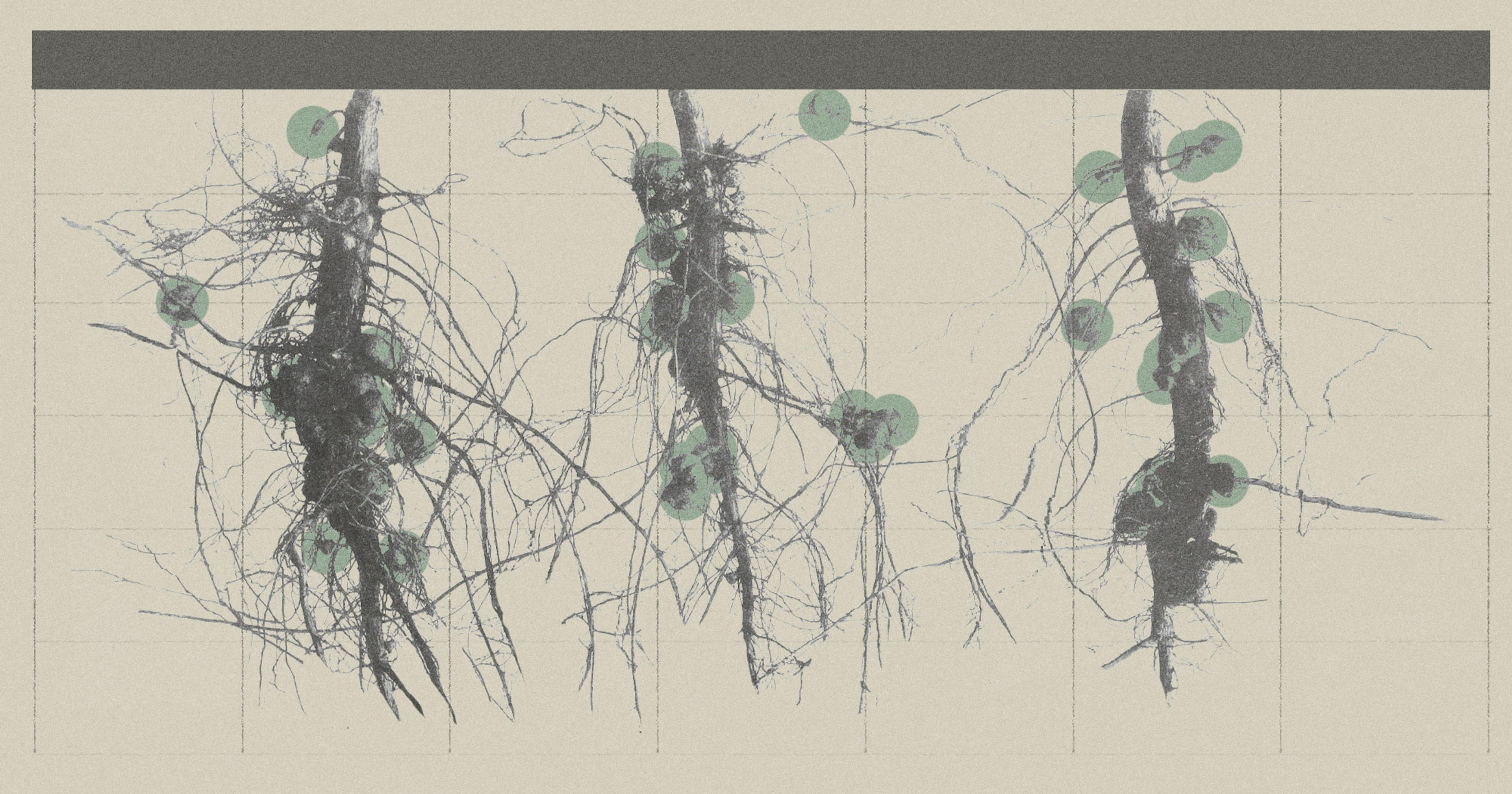

In 2020, organic farmers, the Center for Food Safety, and other stakeholders filed a lawsuit in response to the USDA’s decision to grant hydroponic farms the ability to label their produce organic. The opposition stems from the core of what, exactly, “organic” means. A major pillar of traditional organic farming is intentionally building up the fertility and health of soil. Because the vertical systems operate without soil at all, the suit claims it is impossible for the systems to be truly organic.

The lawsuit has since failed, and soilless operations could potentially label their products organic — though Kalera, AeroFarms, and many other large growing operations still don’t technically meet USDA’s organic requirements at present. At Kalera, that’s not the company’s current focus. “It would require a shift,” said Nissen. “Basically, the fertilizers have to be water soluble, and our systems are very fine-tuned right now. So that would require some change, but it’s certainly possible.” Still, some tension between traditional outdoor farms and vertical indoor operations remains.

Instead of an either/or, the brightest future for indoor farming would be to provide a reprieve of pressure on outdoor farms, with both types of growers working together to strengthen the food system as a whole.

“Controlled environmental agriculture is going to grow leaps and bounds faster than traditional,” said Nissen. “We’re experiencing higher highs and lower lows, and more and more violence in terms of weather. To support larger markets and larger urban communities is the goal. And we’re going to need both conventional and controlled agriculture for that,” said Nissen.